Abstract

Purpose

Fatigue is frequent and often severe and disabling in RA, and there is no consensus on how to measure it. We used online surveys and in-person interviews to evaluate PROMIS Fatigue 7a and 8a short forms (SFs) in people with RA.

Methods

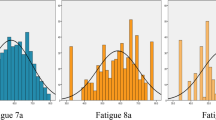

We recruited people with RA from an online patient community (n = 200) and three academic medical centers (n = 84) in the US. Participants completed both SFs then rated the comprehensiveness and comprehensibility of the items to their fatigue experience. Cognitive debriefing of items was conducted in a subset of 32 clinic patients. Descriptive statistics were calculated, and associations were evaluated using Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients.

Results

Mean SF scores were similar (p ≥ .61) among clinic patients reflecting mild fatigue (i.e., 54.5–55.9), but were significantly higher (p < .001) in online participants. SF Fatigue scores correlated highly (r ≥ 0.82; p < .000) and moderately with patient assessments of disease activity (r ≥ 0.62; p = .000). Most (70–92%) reported that the items “completely” or “mostly” reflected their experience. Almost all (≥ 94%) could distinguish general fatigue from RA fatigue. Most (≥ 85%) rated individual items questions as “somewhat” or “very relevant” to their fatigue experience, averaged their fatigue over the past 7 days (58%), and rated fatigue impact versus severity (72 vs. 19%). 99% rated fatigue as an important symptom they considered when deciding how well their current treatment was controlling their RA.

Conclusions

Results suggest that items in the single-score PROMIS Fatigue SFs demonstrate content validity and can adequately capture the wide range of fatigue experiences of people with RA.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bartlett, S. J., Hewlett, S., Bingham 3rd, C. O., Woodworth, T. G., Alten, R., Pohl, C., et al. (2012). Identifying core domains to assess flare in rheumatoid arthritis: An OMERACT International patient and provider combined Delphi consensus. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 71(11), 1855–1860.

Hewlett, S., Cockshott, Z., Byron, M., Kitchen, K., Tipler, S., Pope, D., et al. (2005). Patients’ perceptions of fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: Overwhelming, uncontrollable, ignored. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 53(5), 697–702.

Katz, P. (2017). Fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis. Current Rheumatology Reports, 19(5), 25.

Kirwan, J. R., & Hewlett, S. (2007). Patient perspective: Reasons and methods for measuring fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis. The Journal of Rheumatology, 34(5), 1171–1173.

Kvien, T. K. (2004). Epidemiology and burden of illness of rheumatoid arthritis. Pharmacoeconomics, 22(2), 1–12.

Alten, R., Pohl, C., Choy, E. H., Christensen, R., Furst, D. E., Hewlett, S. E., et al. (2011). Developing a construct to evaluate flares in rheumatoid arthritis: A conceptual report of the OMERACT RA Flare Definition Working Group. The Journal of Rheumatology, 38(8), 1745–1750.

Kirwan, J. R., Minnock, P., Adebajo, A., Bresnihan, B., Choy, E., de Wit, M., et al. (2007). Patient perspective: Fatigue as a recommended patient centered outcome measure in rheumatoid arthritis. The Journal of Rheumatology, 34(5), 1174–1177.

Aletaha, D., Landewe, R., Karonitsch, T., Bathon, J., Boers, M., Bombardier, C., et al. (2008). Reporting disease activity in clinical trials of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: EULAR/ACR collaborative recommendations. Arthritis Care & Research, 59(10), 1371–1377.

Felson, D. T., Smolen, J. S., Wells, G., Zhang, B., van Tuyl, L. H., Funovits, J., et al. (2011). American College of Rheumatology/European League against rheumatism provisional definition of remission in rheumatoid arthritis for clinical trials. Arthritis & Rheumatology, 63(3), 573–586.

Khanna, D., Krishnan, E., Dewitt, E. M., Khanna, P. P., Spiegel, B., & Hays, R. D. (2011). Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS(R))—the future of measuring patient reported outcomes in rheumatology. Arthritis Care Research (Hoboken), 63(S11), S486–S90.

Cella, D., Riley, W., Stone, A., Rothrock, N., Reeve, B., Yount, S., et al. (2010). The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 63(11), 1179–1194.

Christodoulou, C., Junghaenel, D. U., DeWalt, D. A., Rothrock, N., & Stone, A. A. (2008). Cognitive interviewing in the evaluation of fatigue items: Results from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Quality of life research: An international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment. Care and Rehabilitation, 17(10), 1239–1246.

Lai, J. S., Cella, D., Choi, S., Junghaenel, D. U., Christodoulou, C., Gershon, R., et al. (2011). How item banks and their application can influence measurement practice in rehabilitation medicine: A PROMIS fatigue item bank example. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 92(10 Suppl), S20–S27.

Cella, D., Lai, J. S., Jensen, S. E., Christodoulou, C., Junghaenel, D. U., Reeve, B. B., et al. (2016). PROMIS fatigue item bank had clinical validity across diverse chronic conditions. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 73, 128–134.

Bartlett, S. J., Orbai, A. M., Duncan, T., DeLeon, E., Ruffing, V., Clegg-Smith, K., et al. (2015). Reliability and validity of selected PROMIS measures in people with rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS ONE, 10(9), e0138543.

Bingham 3rd, C. O., Noonan, V., Auger, C., Feldman, D., Ahmed, S., & Bartlett, S. J. (2017) Montreal Accord on Patient-Reported Outcomes use series—paper 4: Patient Reported Outcomes (PRO) can inform clinical decision-making in chronic care. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 89, 136–141.

Bingham 3rd, C. O., Bartlett, S. J., Merkel, P. A., Mielenz, T. J., Pilkonis, P. A., Edmundson, L., et al. (2016). Using Patient-Reported Outcomes and PROMIS in research and clinical applications: Experiences from the PCORI pilot projects. Quality of Life Research, 25(8), 2109–2116.

Food and Drug Administration. (2009) Guidance for Industry—Patient-Reported Outcome measures: Use in medical product development to support labeling claims, Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services, Retrieved August 1, 2017, from http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf.

Patrick, D. L., Burke, L. B., Gwaltney, C. J., Leidy, N. K., Martin, M. L., Molsen, E., et al. (2011). Content validity–establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO Good Research Practices Task Force Report: Part 2—assessing respondent understanding. Value in Health, 14(8), 978–988.

Karlson, E. W., Sanchez-Guerrero, J., Wright, E. A., Lew, R. A., Daltroy, L. H., Katz, J. N., et al. (1995). A connective tissue disease screening questionnaire for population studies. Annals of Epidemiology, 5(4), 297–302.

Aletaha, D., Neogi, T., Silman, A. J., Funovits, J., Felson, D. T., & Bingham 3rd, C. O. (2010). 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: An American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis & Rheumatology, 62(9), 2569–2581.

Taylor, W., Gladman, D., Helliwell, P., Marchesoni, A., Mease, P., Mielants, H., et al. (2006). Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: Development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis & Rheumatology, 54(8), 2665–2673.

Deng, N., Guyer, R., & Ware, J. E. (2015). Energy, fatigue, or both? A bifactor modeling approach to the conceptualization and measurement of vitality. Quality of Life Research, 24(1), 81–93.

Hewlett, S., Dures, E., & Almeida, C. (2011) Measures of fatigue: Bristol rheumatoid arthritis fatigue multi-dimensional questionnaire (BRAF MDQ), Bristol rheumatoid arthritis fatigue numerical rating scales (BRAF NRS) for severity, effect, and coping, Chalder fatigue questionnaire (CFQ), checklist individual strength (CIS20R and CIS8R), fatigue severity scale (FSS), functional assessment chronic illness therapy (fatigue) (FACIT‐F), multi-dimensional assessment of fatigue (MAF), multi-dimensional fatigue inventory (MFI), pediatric quality of life (PEDSQL) multi-dimensional fatigue scale, profile of fatigue (PROF), short form 36 vitality subscale (SF-36 VT), and visual analog scales (VAS). Arthritis Care & Research, 63 (Suppl 11), S263–S286.

Oude Voshaar, M. A., Ten Klooster, P. M., Bode, C., Vonkeman, H. E., Glas, C. A., Jansen, T., et al. (2015). Assessment of fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: A psychometric comparison of single-item, multiitem, and multidimensional measures. Journal of Rheumatology, 42(3), 413–420.

Wolfe, F. (2004). Fatigue assessments in rheumatoid arthritis: Comparative performance of visual analog scales and longer fatigue questionnaires in 7760 patients. Journal of Rheumatology, 31(10), 1896–1902.

Simons, G., Belcher, J., Morton, C., Kumar, K., Falahee, M., Mallen, C. D., et al. (2017). Symptom recognition and perceived urgency of help-seeking for rheumatoid arthritis and other diseases in the general public: A mixed method approach. Arthritis Care & Research, 69(5), 633–641.

Shiyanbola, O. O., & Farris, K. B. (2010). Variation in patients’ and pharmacists’ attribution of symptoms and the relationship to patients’ concern beliefs in medications. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 6(4), 334–344.

Nijrolder, I., Leone, S. S., & van der Horst, H. E. (2015). Explaining fatigue: An examination of patient causal attributions and their (in)congruence with family doctors’ initial causal attributions. European Journal of General Practice, 21(3), 164–169.

Horne, R., & Weinman, J. (1999). Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 47(6), 555–567.

Stack, R. J., Shaw, K., Mallen, C., Herron-Marx, S., Horne, R., & Raza, K. (2012). Delays in help seeking at the onset of the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic synthesis of qualitative literature. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 71(4), 493–497.

Tweehuysen, L., van den Bemt, B. J. F., van Ingen, I. L., de Jong, A. J. L., van der Laan, W. H., van den Hoogen, F. H. J., et al. (2018). Subjective complaints as the main reason for biosimilar discontinuation after open-label transition from reference infliximab to Biosimilar Infliximab. Arthritis & Rheumatology, 70(1), 60–68.

Rose, M., Bjorner, J. B., Gandek, B., Bruce, B., Fries, J. F., & Ware, J. E. (2014). Jr. The PROMIS physical function item bank was calibrated to a standardized metric and shown to improve measurement efficiency. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(5), 516–526.

Kirwan, J. R., Minnock, P., Adebajo, A., Bresnihan, B., Choy, E., de Wit, M., et al. (2007). Patient perspective: Fatigue as a recommended patient centered outcome measure in rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Rheumatology, 34(5), 1174–1177.

Ware, J. E. Jr., & Sherbourne, C. D. (1992). The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care, 30(6), 473–483.

Webster, K., Cella, D., & Yost, K. (2003). The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) measurement system: Properties, applications, and interpretation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 1, 79–79.

Cella, D., Yount, S., Sorensen, M., Chartash, E., Sengupta, N., & Grober, J. (2005). Validation of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy Fatigue Scale relative to other instrumentation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The Journal of Rheumatology, 32(5), 811–819.

Allaire, S., Wolfe, F., Niu, J., & Lavalley, M. P. (2008). Contemporary prevalence and incidence of work disability associated with rheumatoid arthritis in the US. Arthritis Care & Research, 59(4), 474–480.

Nicklin, J., Cramp, F., Kirwan, J., Greenwood, R., Urban, M., & Hewlett, S. (2010). Measuring fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: A cross-sectional study to evaluate the Bristol rheumatoid arthritis fatigue multi-dimensional questionnaire, visual analog scales, and numerical rating scales. Arthritis Care & Research, 62(11), 1559–1568.

PROMIS Health Organization (2015) A brief guide to the PROMIS fatigue instruments: Health Measures, Updated 9/9/2015; cited 2018 from, https://www.assessmentcenter.net/documents/PROMIS%20Fatigue%20Scoring%20Manual.pdf.

Mesa, R. A., Gotlib, J., Gupta, V., Catalano, J. V., Deininger, M. W., Shields, A. L., et al. (2013). Effect of ruxolitinib therapy on myelofibrosis-related symptoms and other Patient-Reported Outcomes in COMFORT-I: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 31(10), 1285–1292.

Wild, D., Eremenco, S., Mear, I., Martin, M., Houchin, C., Gawlicki, M., et al. (2009). Multinational trials-recommendations on the translations required, approaches to using the same language in different countries, and the approaches to support pooling the data: The ISPOR Patient-Reported Outcomes translation and linguistic validation good research practices task force report. Value Health, 12(4), 430–440.

Alonso, J., Bartlett, S. J., Rose, M., Aaronson, N. K., Chaplin, J. E., Efficace, F., et al. (2013). The case for an international Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) initiative. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 11, 210.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank research teams at Johns Hopkins, Hospital for Special Surgery, and University of Alabama at Birmingham for their assistance (Michelle Jones, Bernadette Johnson, Kathleen Andersen, Jessica Ashley), and the rheumatologists and trainees who referred patients for participation in the studies. We gratefully acknowledge assistance from Global Healthy Living Foundation for access to an online arthritis patient community through CreakyJoints.org and technical support from David Curtis. We thank members of our external advisory group to this project, including our patient research partners Ms. Amye Leong and Ms. Anne Lyddiatt, in addition to Dr. James Witter and Dr. April Naegeli.

Disclosures

Dr. Bartlett is an unpaid non-voting member of the RA Working Group of the C-Path PRO Consortium and is an unpaid member of the steering committees for PROMIS International, the OMERACT Drug Safety Group, the Scleroderma Patient-centered Interventions Network (SPIN), Cancer Care Ontario, and Canada-PRO. She has served as a consultant to Eli Lilly, Janssen, Pfizer, Merck, and UCB in the area of patient-reported outcomes. Dr. Bykerk has consulted for Amgen, BMS, Pfizer, Sanofi/Regeneron, Gilead, and UCB; she has participated in advisory boards for Amgen, BMS, Pfizer, Sanofi/Regeneron, Gilead. Amgen, BMS, UCB have funded studies that are being or were recently performed at HSS where Dr. Bykerk is or was an investigator or principle investigator or site principle investigator on these studies. Dr. Orbai received research funding to Johns Hopkins University from Celgene, Eli Lilly, Horizon, Janssen, Novartis, and Pfizer. Dr. Orbai received consulting fees from participating in advisory boards for Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB. Dr. Bingham is an unpaid non-voting member of the RA Working Group of the C-Path PRO Consortium and is an unpaid member of the executive committee of OMERACT (Outcome Measures in Rheumatology) which has been funded by arm’s length funding from 32 pharmaceutical companies and research organizations. He has served as a consultant to Eli Lilly, Janssen, Pfizer, and UCB in the area of patient-reported outcomes. All other authors declare that he/she has no conflict of interest.

Funding

The primary research data included within this report were acquired as part of projects funded in part from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) through a PCORI Methods Award (SC14-1402-10818). This work was also supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through the Rheumatic Diseases Resource-based Core Center (P30-AR053503 Cores A and D, and P30-AR070254, Cores A and B), a research agreement from the Critical Path Institute (C-Path) to Johns Hopkins, and the Camille Julia Morgan Arthritis Research and Education Fund. All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of PCORI, its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee, of the NIH or the National Institute of Arthritis Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), or of the PROMIS Health Organization (PHO).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bartlett, S.J., Gutierrez, A.K., Butanis, A. et al. Combining online and in-person methods to evaluate the content validity of PROMIS fatigue short forms in rheumatoid arthritis. Qual Life Res 27, 2443–2451 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1880-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1880-x