Abstract

Key message

The foliage characters found in Casuarina seedlings may represent the ancestral, scleromorphic ones found in the Casuarinaceae. In the adults studied, these are replaced by derived xeromorphic features.

Abstract

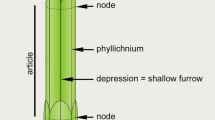

The ontogenetic changes in the foliage of two Casuarina species were investigated. While the cotyledons are flattened linear structures, all other leaf-types are strongly reduced. Except for the two primary leaves, all subsequent leaves are strongly fused to each other and also to the shoot axis, except for the leaf tips; the shoot axis is completely surrounded by photosynthetic leaf tissue and the branchlet is not made up of cladodes but of extended leaf sheaths which are a novel strategy for achieving reduced photosynthetic area. In seedlings there are four leaves per node, forming four shallow vertical furrows where light-exposed and non-encrypted stomata are developed. These features are also developed in the adult foliage within the strictly scleromorphic genus Gymnostoma, clearly the most mesic of the present day genera of Casuarinaceae and very likely to include the ancestral types. Thus, we assume that the Casuarina-seedling leaves reflect the ancestral scleromorphic condition. In the adult foliage, the number of leaves per node is strongly increased, which leads to the formation of several nearly closed vertical furrows on the shoot, where stomata are shaded and strongly encrypted. Thus, the adult foliage shows several xeromorphic features that are absent in the juvenile foliage. Our morpho-anatomical data mapped on ecological and palaeobotanical data show that within Casuarinaceae the foliage shifted from scleromorphic to xeromorphic. Thus, the adult xeromorphic foliage in Casuarina is the derived, advanced state.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ashton DH, Bond H, Morris GC (1975) Drought damage on Mount Towrong, Victoria. Proc Linn Soc New South Wales 100:44–69

Beadle NCW (1966) Soil phosphate and its role in molding segments of the Australian flora and vegetation with special reference to xeromorphy and sclerophylly. Ecology 47:992–1007

Blum A (1996) Crop responses to drought and the interpretation of adaptation. Plant Growth Regul 20:135–148

Blum A, Arkin GF (1984) Sorghum root growth and water use as affected by water supply and growth duration. Field Crop Res 9:131–142

Boland DJ, Brooker MIH, Chippendale GM, Hall N, Hyland BPM, Johnston RD, Kleinig DA, McDonald, MW, Turner JD (2006) Forest trees of Australia, 5th edn. CSIRO, Collingwood

Bosabalidis AM, Kofidis G (2002) Comparative effects of drought stress on leaf anatomy of two olive cultivars. Plant Sci 163:375–379

Cutler HC (1939) Monograph of the North American species of the genus Ephedra. Ann Mo Bot Gard 26:373–428

Dörken VM (2013) Leaf dimorphism in Thuja plicata and Platycladus orientalis (thujoid Cupressaceae s. str., Coniferales): the changes in morphology and anatomy from juvenile needle leaves to mature scale leaves. Plant Syst Evol 299:1991–2001

Dörken VM (2014) Leaf-morphology and leaf-anatomy in Ephedra altissima Desf. (Ephedraceae, Gnetales) and their evolutionary relevance. Feddes Repert 123:243–255

Dörken VM, Jagel A (2014) Pinus sylvestris—Wald-Kiefer (Pinaceae), Baum des Jahres 2007. Jahrb Bochumer Bot Ver 5:246–254

Dörken VM, Parsons R (2016) Morpho-anatomical studies on the change in the foliage of two imbricate-leaved New Zealand podocarps: Dacrycarpus dacrydioides and Dacrydium cupressinum. Plant Syst Evol 302:41–54

Düll R, Kutzelnigg H (2011) Taschenlexikon der Pflanzen Deutschlands und angrenzender Länder, 7th edn. Quelle & Meyer, Wiebelsheim

Eckenwalder JE (2009) Conifers of the World. Timber Press, Portland

Farjon A (2005) A monograph of Cupressaceae and Sciadopitys. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Farjon A (2010a) A handbook of the world’s conifers, vol I. Brill, Leiden

Farjon A (2010b) A handbook of the world’s conifers, vol II. Brill, Leiden

Feustel H (1921) Anatomie und Biologie der Gymnospermenblätter. Beih Bot Centralbl 38:177–253

Foster AS, Gifford EM (1974) Comparative morphology of vascular plants. 2nd edn. Freeman, San Francisco

Freitag H, Maier-Stolte M (2003) The genus Ephedra in NE tropical Africa. Kew Bull 58:415–426

Gaskin JF (2003) Tamaricaceae. In: Kubitzki K, Bayer C (eds) The families and genera of vascular plants, vol 5. Springer, Berlin, pp 336–338

Gerlach, D (1984) Botanische Mikrotomtechnik, eine Einführung. 2nd edn. Thieme, Stuttgart

Heywood VH (1978) Flowering plants of the world. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Hill RS (1990) Evolution of the modern high latitude southern hemisphere flora. Evidence from the Australian macrofossil record. In: Douglas JG, Christophel DC (eds) Proceedings 3rd IOP conference, Melbourne 1988. A-Z Publishers, Melbourne, pp 31–42

Hill RS (1998) Fossil evidence for the onset of xeromorphy and scleromorphy in Australian Proteaceae. Aust Syst Bot 11:391–400

Hill RS, Brodribb TJ (2001) Macrofossil evidence for the onset of xeromorphy in Australian Casuarinaceae and tribe Banksieae (Proteaceae). J Mediterr Ecol 2:127–136

Hill RS, Merrifield HE (1993) An early Tertiary macroflora from West Dale, southwestern Australia. Alcheringa 17:285–326

Inamdar JA, Bhatt DC (1971) Epidermal structure and ontogeny of stomata in vegetative and reproductive organs of Ephedra and Gnetum. Ann Bot (Oxford) 36:1041–1046

Korner C (2003) Alpine plant life, 2nd edn. Springer, Berlin

Krüssmann G (1976) Handbuch der Laubgehölze, vol. 1, 2nd edn. Parey, Berlin

Krüssmann G (1977) Handbuch der Laubgehölze, vol 2, 2nd edn. Parey, Berlin

Krüssmann G (1978) Handbuch der Laubgehölze, vol. 3, 2nd edn. Parey, Berlin

Krüssmann G (1983) Handbuch der Nadelgehölze, 2nd edn. Parey, Berlin

Kubitzki K (2004) The families and genera of vascular plants, vol 6. Flowering plants, dicotyledons: Celastrales, Oxalidales, Rosales, Cornales, Ericales. Springer, Berlin

Kubitzki K, Rohwer JG, Bittrich V (1993) The families and genera of vascular plants, vol 2. Flowering plants, dicotyledons: Magnoliid, Hamamelid and Caryophylloid families. Springer, Berlin

Ladd PG (1988) The status of Casuarinaceae in Australian Forests. In: Frawley KJ, Semple NM (eds) Australia’s ever changing forests. Proceedings of the first national conference on Australian forest history, pp 63–85

Loveless AR (1961) A nutritional interpretation of sclerophylly based on differences in the chemical composition of sclerophyllous and mesophytic leaves. Ann Bot (Oxford) 25:168–184

Loveless AR (1962) Further evidence to support a nutritional interpretation of sclerophylly. Ann Bot (Oxford) 26:551–561

Niinemets Ü, Lukjanova A, Sparrow AD, Turnbull MH (2005) Light acclimation of cladode photosynthetic potentials in Casuarina glauca: trade-offs between physiological and structural investments. Funct Plant Biol 32:571–582

Parsons RF (2010) Whipcord plants: a comparison of south-eastern Australia with New Zealand. Cunninghamia 11:277–281

Pedley L (1986) Derivation and dispersal of Acacia (Leguminosae), with particular reference to Australia and the recognition of Senegalia and Racosperma. Bot J Linn Soc 92:219–254

Rao AN (1972) Anatomical studies on succulent cladodes in Casuarina equisetifolia Linn. Proc Indian Acad Sci B 76:262–270

Reddel P, Yun Y, Shipton WA (1997) Cluster roots and mycorrhizae in Casuarina cunninghamiana: their occurrence and formation in relation to phosphorus supply. Aust J Bot 45:41–51

Reddell P, Bowen GD, Robson AD (1986) Nodulation of Casuarinaceae in relation to host species and soil properties. Aust J Bot 34:435–444

Rehder A (1967) Manual of cultivated trees and shrubs, 2nd edn. The Macmillan Company, New York

Salleo S, Nardini A (2000) Sclerophylly: evolutionary advantage or mere epiphenomenon. Plant Biosyst 134(3):247–259

Schütt P, Schuck HJ, Stimm B (2002) Lexikon der Baum- und Straucharten. Nikol, Hamburg

Scriven LJ, Hill RS (1995) Macrofossil Casuarinaceae, their identification and the oldest macrofossil record, Gymnostoma antiquum sp. nov., from the Late Palaeocene of New South Wales, Australia. Aust Syst Bot 8:1035–1053

Seddon G (1974) Xerophytes, xeromorphs and sclerophylls: the history of some concepts in ecology. Biol J Linn Soc 6:65–87

Seidling W, Ziche D, Beck W (2012) Climate responses and interrelations of stem increment and crown transparency in Norway Spruce, Scots Pine and Common Beech. Forest Ecol Manag 284:196–204

Steane DA, Wilson KL, Hill RS (2003) Using matK sequence data to unravel the phylogeny of Casuarinaceae. Mol Phylogenet Evol 28:47–59

Stebbins GL (1950) Variation and evolution in plants. Columbia University Press, New York

Stevens PF (2015) Angiosperm Phylogeny Website, Version 13. http://www.mobot.org/MOBOT/research/-APweb/ (04 Oct 2015)

Taylor TN, Taylor EL, Krings M (2009) Palaeobotany: the biology and evolution of fossil plants. Academic Press, Burlington

Tetzlaf M (2005) Die Anatomie des Gymnospermenblattes unter funktionellen und evolutiven Gesichtspunkten. Diploma. Ruhr-University, Bochum

Thoday D (1931) The significance of reduction in the size of leaves. J Ecol 19(2):297–303

Thompson WP (1912) The anatomy and relationships of Gnetales. I. The genus Ephedra. Ann Bot (Oxford) 27:1077–1104

Torrey JG, Berg RH (1988) Some morphological features for generic characterization among the Casuarinaceae. Am J Bot 75:864–874

Voth PD (1934) A study of the vegetative phases of Ephedra. Bot Gaz 96:298–313

Warrier KCS, Suganthi A, Singh BG (2013) A new record of abnormal phylloclad modification in Casuarina equisetifolia. Int J Agric Sci Res 2:8–11

Wilson KL, Johnson LAS (1989) Casuarinaceae. In: George AS (ed) Flora of Australia, vol 3. Hamamelidales to Casuarinales. Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, pp 100–175

Zamaloa MC, Gandolfo MA, Gonzales CC, Romero EJ, Cuneo NR, Wilf P (2006) Casuarinaceae from the Eocene of Patagonia, Argentina. Int J Plant Sci 167:1279–1289

Zimpfer JF, Igual JM, McCarty B, Smyth C, Dawson JO (2004) Casuarina cunninghamia tissue extracts stimulate the growth of Frankia and differentially alter the growth of other soil microorganisms. J Chem Ecol 30:439–452

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Mr. Otmar Ficht and Mrs. Anne Kern (Botanic Garden, University of Konstanz, Germany) for producing the seedlings. Furthermore, we thank the Botanic Garden of the Ruhr-University of Bochum (Germany) for generously providing research material and Dr. Michael Laumann and Mrs. Lauretta Nejedli (Electron Microscopy Center, Department of Biology, University of Konstanz, Germany) for technical support (paraffin technique). Finally, we thank Dr. Philip Ladd (Murdoch University, Australia), Dr. Mike Bayly (University of Melbourne, Australia) and Dr. Ian Staff (LaTrobe University, Australia) for helpful advice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Communicated by L. Gratani.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dörken, V.M., Parsons, R.F. Morpho-anatomical studies on the leaf reduction in Casuarina: the ecology of xeromorphy. Trees 31, 1165–1177 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-017-1535-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-017-1535-5