Abstract

Purpose

Pregnancy complications (PC) with signs of threatened preterm birth are often associated with lengthy hospital stays, which have been shown to be accompanied by anxiety, depressive symptoms, and increased stress level. It remains unclear, whether the perinatal course of mental health of these women differs from women without PC and whether there may be differences in the postpartum mother–infant bonding.

Methods

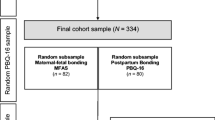

In a naturalistic longitudinal study with two measurements (24–36th weeks of gestation and 6 weeks postpartum), we investigated depression (EPDS), anxiety (STAI-T), stress (PSS), and postpartum mother–infant bonding (PBQ) in women with threatened preterm birth (N = 75) and women without PC (N = 70). For data evaluation, we used means of frequency analysis, analysis of variance with repeated measurements, and t-tests for independent samples.

Results

The patient group showed significantly higher rates of depression, anxiety, and stress during inpatient treatment in pregnancy, as well as 6 weeks postpartum compared to the control group. While depression and anxiety decreased over time in both groups, stress remained at the same level 6 weeks postpartum as in pregnancy. We found no significant differences in mother–infant bonding between the two groups at all considered PBQ scales.

Conclusion

It is recommended to pay attention to the psychological burden of all obstetric patients as a routine to capture a psychosomatic treatment indication. A general bonding problem in women with threatened preterm birth was not found. Nevertheless, increased maternal stress, anxiety, and depressiveness levels during pregnancy may have a negative impact on the development of the fetus.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bendix J, Hegaard HK, Langhoff-Roos J, Bergholt T (2016) Changing prevalence and the risk factors for antenatal obstetric hospitalizations in Denmark 2003-2012. Clin Epidemiol 8:165–175

Liu S, Heaman M, Sauve R et al (2007) Maternal health study group of the canadian perinatal surveillance system: an analysis of antenatal hospitalization in Canada, 1991–2003. Matern Child Health J 11(2):181–187

Raio L (2002) Screening-Untersuchungen auf eine drohende Frühgeburt. Gynaekologe 35(7):661–664

Wolff F (2004) Prävention der Frühgeburt. Gynaekologe 37:737–748

Weidner K, Bittner A, Junge-Hoffmeister J et al (2010) A psychosomatic intervention in pregnant in-patient women with prenatal somatic risks. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 31:188–198

Leichtentritt RD, Blumenthal N, Elyassi A, Rotmensch S (2005) High-risk pregnancy and hospitalization: the women’s voices. Health Soc Work 30:39–47

Witt WP, Wisk LE, Cheng ER, Hampton JM, Hagen EW (2012) Preconception mental health predicts pregnancy complications and adverse birth outcomes: a national population-based study. Matern Child Health J 16(7):1525–1541

Zachariah R (2009) Social support, life stress, and anxiety as predictors of pregnancy complications in low-income women. Res Nurs Health 32(4):391–404

Brandon AR, Trivedi MH, Hynan LS et al (2008) Prenatal depression in women hospitalized for obstetric risk. J Clin Psychiatry 69(4):635–643

Stainton MC, Loha M, Fethney J, Woodhart L, Islam S (2006) Women’s responses to two models of antepartum high-risk care: day stay and hospital stay. Women Birth 19(4):89–95

Lee S, Ayers S, Holden D (2012) Risk perception of women during high risk pregnancy: a systematic review. Health Risk Soc 14(6):511–531

Maloni JA, Chance B, Zhang C, Cohen AW, Betts D, Gange SJ (1993) Physical and psychosocial side effects of antepartum hospital bed rest. Nurs Res 42(4):197–203

Heaman M (1992) Stressful life events, social support, and mood disturbance in hospitalized and non-hospitalized women with pregnancy-induced hypertension. Can J Nurs Res 24(1):23–37

Mercer RT, Ferketich SL (1988) Stress and social support as predictors of anxiety and depression during pregnancy. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 10(2):26–39

Byatt N, Hicks-Courant K, Davidson A et al (2014) Depression and anxiety among high-risk obstetric inpatients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 36(6):644–649

Maloni JA, Park S, Anthony MK, Musil CM (2005) Measurement of antepartum depressive symptoms during high-risk pregnancy. Res Nurs Health 28(1):16–26

Gourounti K, Karapanou V, Karpathiotaki N, Vaslamatzis G (2015) Anxiety and depression of high risk pregnant women hospitalized in two public hospital settings in Greece. Int Arch Med 8(25):1–6

Thiagayson P, Krishnaswamy G, Lim ML, Sung SC, Haley CL, Fung DS et al (2013) Depression and anxiety in Singaporean high-risk pregnancies-prevalence and screening. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 35(2):112–116

Denis A, Michaux P, Callahan S (2012) Factors implicated in moderating the risk for depression and anxiety in high risk pregnancy. J Reprod Infant Psychol 30(2):124–134

Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T (2005) Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol 106(5):1071–1083

Dennis CL, Falah-Hassani K, Shiri R (2017) Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 210(5):315–323

Lobel M, Yali AM, Zhu W, DeVincent C, Meyer B (2002) Beneficial associations between optimistic disposition and emotional distress in high-risk pregnancy. Psychol Health 7(1):77–95

Lobel M, Dunkel-Schetter C (1990) Conceptualizing stress to study effects on health: environmental, perceptual, and emotional components. Anx Res 3(3):213–230

Clauson MI (1996) Uncertainty and stress in women hospitalized with high-risk pregnancy. Clin Nurs Res 5(3):309–325

Woods SM, Melville JL, Guo Y, Fan MY, Gavin A (2010) Psychosocial stress during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 202(1):61.e1–61.e7

Kinsella MT, Monk C (2009) Impact of maternal stress, depression and anxiety on fetal neurobehavioral development. Clin Obstet Gynecol 52:425–440

Staneva A, Bogossian F, Pritchard M, Wittkowski A (2015) The effects of maternal depression, anxiety, and perceived stress during pregnancy on preterm birth: a systematic review. Women Birth 28(3):179–193

Field T (2011) Prenatal depression effects on early development: a review. Inf Beh Dev 34(1):1–14

Van den Bergh BR, Mulder EJ, Mennes M, Glover V (2005) Antenatal maternal anxiety and stress and the neurobehavioural development of the fetus and child: links and possible mechanisms. A review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 29(2):237–258

Iyengar K, Yadav R, Sen S (2012) Consequences of maternal complications in women’s lives in the first postpartum year: a prospective cohort study. J Health Popul Nutr 30(2):226–240

Blom EA, Jansen PW, Verhulst FC, Hofman A et al (2010) Perinatal complications increase the risk of postpartum depression. The Generation R Study. BJOG 117(11):1390–1398

Dubber S, Reck C, Müller M, Gawlik S (2015) Postpartum bonding: the role of perinatal depression, anxiety and maternal–fetal bonding during pregnancy. Arch Womens Ment Health 18(2):187–195

Kinsey CB, Baptiste-Roberts K, Zhu J, Kjerulff KH (2014) Birth-related, psychosocial, and emotional correlates of positive maternal–infant bonding in a cohort of first-time mothers. Midwifery 30(5):e188–e194

Reck C, Klier CM, Pabst K et al (2006) The German version of the Postpartum Bonding Instrument: psychometric properties and association with postpartum depression. Arch Womens Ment Health 9(5):265–271

Feldman R, Weller A, Leckman JF, Kuint J, Eidelman AI (1999) The nature of the mother’s tie to her infant: maternal bonding under conditions of proximity, separation, and potential loss. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 40(6):929–939

Rossen L, Hutchinson D, Wilson J et al (2016) Predictors of postnatal mother–infant bonding: the role of antenatal bonding, maternal substance use and mental health. Arch Womens Ment Health 19(4):609–622

Figueiredo B, Costa R (2009) Mother’s stress, mood and emotional involvement with the infant: 3 months before and 3 months after childbirth. Arch Womens Ment Health 12(3):143–153

Hairston IS, Waxler E, Seng JS, Fezzey AG, Rosenblum KL, Muzik M (2011) The role of infant sleep in intergenerational transmission of trauma. Sleep 34:1373–1383

Priel B, Kantor B (2011) The influence of high-risk pregnancies and social support systems on maternal perceptions of the infant. Infant Ment Health J 9(3):235–244

Handelzalts JE, Krissi H, Levy S et al (2016) Personality, preterm labor contractions, and psychological consequences. Arch Gynecol Obstet 293(3):575–582

Dulude D, Wright J, Bélanger C (2000) The effects of pregnancy complications on the parental adaptation process. J Reprod Infant Psychol 18(1):5–20

Mercer RT, Ferkehch SL (1990) Predictors of parental attachment during early parenthood. J Adv Nurs 15(3):268–280

Dollberg DG, Rozenfeld T, Kupfermincz M (2016) Early parental adaptation, prenatal distress, and high-risk pregnancy. J Pediatr Psychol 41(8):915–929

Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R (1987) Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry 150:782–786

Bergant A, Nguyen T, Moser R, Ulmer H (1998) Prevalence of depressive disorders in early puerperium. Gynaekol geburtshilfliche Rundsch 38(4):232–237

Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE (1970) Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto

Laux L, Glanzmann P, Schaffner P, Spielberger CD (1981) Das State-Trait-Angstinventar: Theoretische Grundlagen und Handanweisung [The state-trait anxiety inventory: theoretical background and manual]. Beltz, Weinheim

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R (1983) A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 24:386–396

Riecker AS (2006) Auswirkungen pränataler Stressbelastung auf die Verhaltensregulation des Kindes. Inaugural-Dissertation, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München

Cohen S (1988) Williamson GM. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacepan S, Oskamp S (eds) The social psychology of health. Sage, Newbury Park, pp 31–67

Brockington IF, Oates J, George S et al (2001) A screening questionnaire for mother–infant bonding disorders. Arch Womens Ment Health 3:133–140

Brockington IF, Fraser C, Wilson D (2006) The postpartum bonding questionnaire: a validation. Arch Womens Ment Health 9(5):233–242

Wittkowski A, Wieck A, Mann S (2007) An evaluation of two bonding questionnaires: a comparison of the Mother-to-Infant Bonding Scale with the Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire in a sample of primiparous mothers. Arch Womens Ment Health 10(4):171–175

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral science, 2nd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale

Entringer S, Buss C, Wadhwa PD (2010) Prenatal stress and developmental programming of human health and disease risk: concepts and integration of empirical findings. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 17(6):507–516

Entringer S, Buss C, Wadhwa PD (2015) Prenatal stress, development, health and disease risk: a psychobiological perspective-2015 Curt Richter Award Paper. Psychoneuroendocrinology 62:366–375

Bowen A, Bowen R, Butt P, Rahman K, Muhajarine N (2012) Patterns of depression and treatment in pregnant and postpartum women. Can J Psychiatry 57:161–167

Sockol LE, Epperson CN, Barber JP (2011) A meta-analysis of treatments for perinatal depression. Clin Psychol Rev 31(5):839–849

Ben-Sheetrit J, Aizenberg D, Csoka AB, Weizman A, Hermesh H (2015) Post-SSRI sexual dysfunction: clinical characterization and preliminary assessment of contributory factors and dose-response relationship. J Clin Psychopharmacol 35(3):273–278

Yonkers KA, Blackwell KA, Glover J, Forray A (2014) Antidepressant use in pregnant and postpartum women. Ann Rev Clin Psychol 10:369–392

Wirz-Justice A, Bader A, Frisch U et al (2011) A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of light therapy for antepartum depression. J Clin Psychiatry 72(7):986–993

Field T, Diego M, Hernandez-Reif M, Medina L, Delgado J, Hernandez A (2012) Yoga and massage therapy reduce prenatal depression and prematurity. J Body Work Mov Ther 16(2):204–209

Manber R, Schnyer RN, Lyell D et al (2010) Acupuncture for depression during pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Deutsche Zeitschrift für Akupunktur 53(2):43–45

Bauer CL, Victorson D, Rosenbloom S, Barocas J, Silver RK (2010) Alleviating distress during antepartum hospitalization: a randomized controlled trial of music and recreation therapy. J Womens Health 19(3):523–531

Robertson E, Grace S, Wallington T, Stewart DE (2004) Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: a synthesis of recent literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 26(4):289–295

Weidner K, Einsle F, Köllner V, Haufe K, Joraschky P, Distler W (2004) Werden Patientinnen mit psychosomatischen Befindlichkeitsstörungen im Alltag einer Frauenklinik erkannt? Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 64(5):479–490

Acknowledgements

We specifically thank all participants of our trial for their willingness, time, and effort to answer the questionnaires. Furthermore, the authors thank the physicians and nursery staff of the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, University Hospital Carl Gustav Carus, TU Dresden, Dresden, Germany for their support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HC, BA, and WK designed the study. HC performed the analysis and wrote the manuscript in consultation with BA. JJH, MS, NK, and WK revised the manuscript for critical input. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest and are solely responsible for the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hanko, C., Bittner, A., Junge-Hoffmeister, J. et al. Course of mental health and mother–infant bonding in hospitalized women with threatened preterm birth. Arch Gynecol Obstet 301, 119–128 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-019-05406-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-019-05406-3