Abstract

Purpose

We aimed to (1) to investigate mortality trends due to suicide in Panama at the national and regional levels from 2001 to 2016, (2) to describe the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of admitted patients with non-fatal self-harm from 2009 to 2017 in a regional hospital, and (3) to examine the association between mental health diagnoses and intentional self-harm, lethality, self-harm repetition and all-cause mortality within this population.

Methods

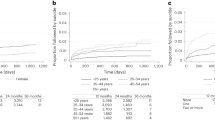

Using the national mortality registry, annual percentage changes (APC) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated to evaluate suicide trends over time. Self-harm cases were assessed by trained psychiatrists at a referral hospital through interviews. Logistic regression models were used to estimate the association between mental diagnosis with intent-to-die and lethality, expressed as odds ratios (OR) and 95% CI. Cox proportional hazards models were used to calculate hazard ratios (HR) with 95% CI for self-harm repetition and all-cause mortality.

Results

The trend of suicide in women declined, with an APC of − 4.8, 95% CI − 7.8, − 1.7, while the trend began to decline from 2006 in men; APC − 6.9, 95% CI − 8.9, − 4.9. Self-harm repetition over 12 months was 1.8%. Having a mental health diagnosis was associated with intentional self-harm (OR 1.5; 95% CI 1.0–2.4) and self-harm repetition (HR 2.7, 95% CI 1.3–5.8). Medication overdose was the preferred method for self-harm, while intentional self-harm by hanging was the preferred method for suicide.

Conclusions

Strategies for prevention and early intervention after self-harm deserve attention. Our findings highlight the importance of data to inform action.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Code availability

Stata version14.

References

Naghavi M, Global Burden of Disease Self-Harm C (2019) Global, regional, and national burden of suicide mortality 1990 to 2016: systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. BMJ 364:l9

Fazel S, Runeson B (2020) Suicide. N Engl J Med 382(3):266–274

Zalsman G, Hawton K, Wasserman D, van Heeringen K, Arensman E, Sarchiapone M et al (2016) Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry 3(7):646–659

World Health Organization (2019) Preventing suicide: a global imperative. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/131056/9789241564779_eng.pdf;jsessionid=13F6C34C1085AE3E7A00B8C89C2509B7?sequence=1. Accessed on Oct 2019

Hawton K, Zahl D, Weatherall R (2003) Suicide following deliberate self-harm: long-term follow-up of patients who presented to a general hospital. Br J Psychiatry 182:537–542

Pan American Health Organzation (2019). https://www.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2014/PAHO-mortality-suicide--final.pdf. Accessed on Oct 2019

Teti GL, Rebok F, Rojas SM, Grendas L, Daray FM (2014) Systematic review of risk factors for suicide and suicide attempt among psychiatric patients in Latin America and Caribbean. Rev Panam Salud Publica 36(2):124–133

Ministry of Health (2020). https://www.minsa.gob.pa/informacion-salud/poblacion. Accessed on Jan 2020

Instituto Nacional de Estadistica y Censo (2020). https://www.inec.gob.pa/archivos/P6751Bolet%C3%ADn%252018.%2520ESTIMACIONES%2520Y%2520PROYECCIONES.pdf. Accessed on Jan 2020

World Health Organization Mental Health Gap Action Programme (2020). https://www.who.int/mental_health/mhgap/en/. Accessed on May 2020

Gaceta Oficial resolución No 508 Ministerio de Salud (2020). https://gacetas.procuraduria-admon.gob.pa/28833_2019.pdf. Accessed on May 2020

Mikkelsen L, Phillips DE, AbouZahr C, Setel PW, de Savigny D, Lozano R et al (2015) A global assessment of civil registration and vital statistics systems: monitoring data quality and progress. Lancet 386(10001):1395–1406

Carrion Donderis M, Moreno Velasquez I, Castro F, Zuniga J, Gomez B, Motta J (2016) Analysis of mortality trends due to cardiovascular diseases in Panama, 2001–2014. Open Heart 3(2):e000510

Ministry of Health (2020). https://www.minsa.gob.pa/sites/default/files/general/asis_panama_oeste_2018.pdf. Accessed on Jan 2020

Clements C, Hawton K, Geulayov G, Waters K, Ness J, Rehman M et al (2019) Self-harm in midlife: analysis using data from the Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England. Br J Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.90

International Standard Classification of Occupations (2020). https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_172572.pdf. Accessed on Jan 2020

WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology (2020). https://www.whocc.no/atc/structure_and_principles/. Accessed on Jan 2020

National Cancer Institute (2020) Division of Cancer Control & Population Sciences. Surveillance Research Program. Number of joinpoints. https://surveillance.cancer.gov/help/joinpoint/setting-parameters/advanced-tab/number-of-joinpoints. Accessed on Apr 2020

Ortiz-Prado E, Simbana K, Gomez L, Henriquez-Trujillo AR, Cornejo-Leon F, Vasconez E et al (2017) The disease burden of suicide in Ecuador, a 15 years' geodemographic cross-sectional study (2001–2015). BMC Psychiatry 17(1):342

Fassberg MM, van Orden KA, Duberstein P, Erlangsen A, Lapierre S, Bodner E et al (2012) A systematic review of social factors and suicidal behavior in older adulthood. Int J Environ Res Public Health 9(3):722–745

Lapierre S, Erlangsen A, Waern M, De Leo D, Oyama H, Scocco P et al (2011) A systematic review of elderly suicide prevention programs. Crisis 32(2):88–98

Bustamante F, Ramirez V, Urquidi C, Bustos V, Yaseen Z, Galynker I (2016) Trends and most frequent methods of suicide in Chile between 2001 and 2010. Crisis 37(1):21–30

Orellana JD, Balieiro AA, Fonseca FR, Basta PC, Souza ML (2016) Spatial-temporal trends and risk of suicide in Central Brazil: an ecological study contrasting indigenous and non-indigenous populations. Braz J Psychiatry 38(3):222–230

Ministry of Social Development (2020). https://www.mides.gob.pa/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Informe-del-%C3%8Dndice-de-Pobreza-Multidimensional-de-Panam%C3%A1-2017.pdf. Accesed on Jan 2020

Ministry of Health (2020). https://www.minsa.gob.pa/sites/default/files/publicaciones/asis_final_2018c.pdf. Accessed on Jan 2020

O'Farrell IB, Corcoran P, Perry IJ (2016) The area level association between suicide, deprivation, social fragmentation and population density in the Republic of Ireland: a national study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 51(6):839–847

Brenner B, Cheng D, Clark S, Camargo CA, Jr. (2011) Positive association between altitude and suicide in 2584 U.S. counties. High Alt Med Biol 12(1):31–5

Kious BM, Kondo DG, Renshaw PF (2018) Living high and feeling low: altitude, suicide, and depression. Harv Rev Psychiatry 26(2):43–56

Harris IM, Beese S, Moore D (2019) Predicting future self-harm or suicide in adolescents: a systematic review of risk assessment scales/tools. BMJ Open 9(9):e029311

Hansson K, Malmkvist L, Johansson BA (2020) A 15-year follow-up of former self-harming inpatients in child & adolescent psychiatry - a qualitative study. Nord J Psychiatry. 74(4):273–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039488.2019.1697747

Diamond GS, Herres JL, Krauthamer Ewing ES, Atte TO, Scott SW, Wintersteen MB et al (2017) Comprehensive screening for suicide risk in primary care. Am J Prev Med 53(1):48–54

Hawton K, Saunders KE, O'Connor RC (2012) Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet 379(9834):2373–2382

Wasserman D, Hoven CW, Wasserman C, Wall M, Eisenberg R, Hadlaczky G et al (2015) School-based suicide prevention programmes: the SEYLE cluster-randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 385(9977):1536–1544

Carroll R, Metcalfe C, Gunnell D (2014) Hospital presenting self-harm and risk of fatal and non-fatal repetition: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 9(2):e89944

Zahl DL, Hawton K (2004) Repetition of deliberate self-harm and subsequent suicide risk: long-term follow-up study of 11,583 patients. Br J Psychiatry 185:70–75

Runeson B, Haglund A, Lichtenstein P, Tidemalm D (2016) Suicide risk after nonfatal self-harm: a national cohort study, 2000–2008. J Clin Psychiatry 77(2):240–246

Chesney E, Goodwin GM, Fazel S (2014) Risks of all-cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: a meta-review. World Psychiatry 13(2):153–160

Borges G, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Andrade L, Benjet C, Cia A, Kessler RC et al (2019) Twelve-month mental health service use in six countries of the Americas: a regional report from the World Mental Health Surveys. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 29:e53

Kohn R, Ali AA, Puac-Polanco V, Figueroa C, Lopez-Soto V, Morgan K et al (2018) Mental health in the Americas: an overview of the treatment gap. Rev Panam Salud Publica 42:e165

Gunnell D, Eddleston M, Phillips MR, Konradsen F (2007) The global distribution of fatal pesticide self-poisoning: systematic review. BMC Public Health 7:357

World Health Organization (2020) Preventing suicide: a resource for pesticide registrars and regulators. file:///C:/Users/DIETS4/Downloads/9789241516389-eng%2520(2).pdf. Accessed on Jan 2020

Gunnell D, Knipe D, Chang SS, Pearson M, Konradsen F, Lee WJ et al (2017) Prevention of suicide with regulations aimed at restricting access to highly hazardous pesticides: a systematic review of the international evidence. Lancet Glob Health 5(10):e1026–e1037

Hawton K, Simkin S, Deeks J, Cooper J, Johnston A, Waters K et al (2004) UK legislation on analgesic packs: before and after study of long term effect on poisonings. BMJ 329(7474):1076

Darvishi N, Farhadi M, Haghtalab T, Poorolajal J (2015) Alcohol-related risk of suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and completed suicide: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 10(5):e0126870

Witt K, Lubman DI (2018) Effective suicide prevention: Where is the discussion on alcohol? Aust N Z J Psychiatry 52(6):507–508

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by an institutional research grant from Panama. IMV is supported by the Sistema Nacional de Investigación (SNI), Senacyt, Panama.

Funding

Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF), Panama.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval to conduct the study was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee of the Gorgas Memorial Institute for Health Studies (No. 754/CBI/ICGES/18 and No. 708/CBI/ICGES/19). Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the Ministry of Health of Panama and the medical director of the participating hospital.

Consent to participate

Data was retrieved from hospital and mortality registries.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moreno Velásquez, I., Castelpietra, G., Higuera, G. et al. Suicide trends and self-harm in Panama: results from the National Mortality Registry and hospital-based data. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 55, 1513–1524 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01895-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01895-9