Abstract

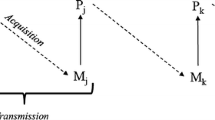

Cultural evolutionists typically emphasize the informational aspect of social transmission, that of the learning, stabilizing, and transformation of mental representations along cultural lineages. Social transmission also depends on the production of public displays such as utterances, behaviors, and artifacts, as these displays are what social learners learn from. However, the generative processes involved in the production of public displays are usually abstracted away in both theoretical assessments and formal models. The aim of this paper is to complement the informational view with a generative dimension, emphasizing how the production of public displays both enable and constrain the production of modular cultural recipes through the process of innovation by recombination. In order to avoid a circular understanding of cultural recombination and cultural modularity, we need to take seriously the nature and structure of the generative processes involved in the maintenance of cultural traditions. A preliminary analysis of what recombination and modularity consist of is offered. It is shown how the study of recombination and modularity depends on a finer understanding of the generative processes involved in the production phase of social transmission. Finally, it is argued that the recombination process depends on the inventive production of an interface between modules and the complex recipes in which they figure, and that such interfaces are the direct result of the generative processes involved in the production of these recipes. The analysis is supported by the case study of the transition from the Oldowan to the Early Acheulean flake detachment techniques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

There is a vast scientific literature concerned with the structure of behaviors. One general point of consensus among cognitive psychologists, neuroscientists, linguists, paleoarcheologists, anthropologists, primatologists, and artificial intelligence researchers is that behaviors are hierarchically organized (Botvinick 2008; Byrne 2003; Byrne and Russon 1998; Chomsky 1957; Greenfield 1991; Guerra-Filho and Aloimonos 2012; Lashley 1951; Mesoudi and Whiten 2004; Miller et al. 1960; Pastra and Aloimonos 2012; Schank and Abelson 1977; Simon 1962; Stout 2011; Whiten 2002). Cultural evolutionists have also noted that complex cultural recipes are hierarchically organized and have studied some of the evolutionary implications of these structures (Enquist et al. 2011; Mesoudi and O’Brien 2008; Mesoudi and Whiten 2004).

Just how we decide what constitutes a basic action unit will not be addressed here in any detail. There has been debates on just what the appropriate level of description is and whether there exists such thing as an atomic action (e.g., Lombard and Haidle 2012; Perreault et al. 2013). For the remainder, we can assume that all agree on the right granularity of description, as what is of interest here is not the proper grain of description for complex behaviors but the implications of their hierarchical structures having different degrees of integration.

The expression is mine, but it is adapted from Moore (2007, 2010) who also develops a hierarchical description of the recipe’s functional structure. However, Moore writes about a “basic flake unit,” which suggests a static view, an object. The active form “flaking” is preferred here as it makes it clearer that the unit is a behavioral/cognitive process and not a material end-result.

Although technically the Early Acheulean technique examined here is not a part of the Acheulean industry, it is nevertheless generally considered part of the transition leading to the Acheulean. See Stout (2011) for discussion.

Following most paleoarcheologists, it is assumed here that the transition from the Oldowan to the Early Acheulean techniques is a cultural (technological) one, made possible (at least in part) by the cultural transmission of the flaking techniques. Some doubts have been raised about this possibility (see Richerson and Boyd 2005; Corbey et al. 2016). Even if it was shown that the Oldowan-Early Acheulean transition was not cultural, the general conceptual analysis developed her would still stand on its own. Moreover, the basic flaking unit is known to be transmissible through social learning as even more sophisticated, clearly cultural techniques employ it (Whittaker 1994).

The case of learning the basic flaking unit might not be generalizable to all modular cultural traditions as we might not expect all cultural recipes to depend on practice and trial-and-error learning. However, the case study shows that the material nature of the generative processes can have an important role in such forms of social learning and will thus be relevant when perpetuating a cultural tradition requires each individual in the chain to practice actions and learn about materials.

References

Arthur, B. (2009). The nature of technology: what it is and how it evolves. New York: Free Press.

Basalla, G. (1988). The evolution of technology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Botvinick, M. M. (2008). Hierarchical models of behavior and prefrontal function. Trends in Cognitive Science, 12(5), 201–208.

Boyd, R., & Richerson, P. J. (1985). Culture and the Evolutionary Process. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Boyer, P. (1999). Cognitive tracks of cultural inheritance: how evolved intuitive ontology governs cultural transmission. American Anthropologist, 100(4), 876–889.

Brandon, R. N. (2005). Evolutionary modules: conceptual analyses and empirical hypotheses. In W. Callebaut & D. Rasskin-Gutman (Eds.), Modularity: understanding the development and evolution of natural complex systems (pp. 51–60). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Braun, D. R., Plummer, T., Ferraro, J. V., Ditchfield, P., & Bishop, L. (2009). Raw material quality and Oldowan hominin toolstone preferences: evidence from Kanjera South, Kenya. Journal of Archaeological Science, 36, 1605–1614.

Byrne, R. W. (2003). Imitation as behaviour parsing. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 358, 529–536.

Byrne, R. W., & Russon, A. E. (1998). Learning by imitation: a hierarchical approach. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 21, 667–721.

Cavalli-Sforza, L. L., & Feldman, M. W. (1981). Cultural transmission and evolution: a quantitative approach. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Charbonneau, M. (2015a). All innovations are equal, but some more than others: (re)integrating modification processes to the origins of cumulative culture. Biological Theory, 10(4), 322–335.

Charbonneau, M. (2015b). Mapping complex social transmission: technical constraints on the evolution cultures. Biology & Philosophy, 30, 527–546.

Chomsky, N. (1957). Syntactic structures. Gravenhage: Mouton & Co.

Claidière, N., & Sperber, D. (2010). Imitation explains the propagation, not the stability of animal culture. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 277, 651–659.

Claidière, N., Scott-Phillips, T. C., & Sperber, D. (2014). How Darwinian is cultural evolution? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 369(1642), 20130368.

Corbey, R., Jagich, A., Vaesen, K., & Collard, M. (2016). The Acheulean handaxe: more like a bird’s song than a Beatles’ tune? Evolutionary Anthropology, 25, 6–19.

de la Torre, I. (2011). The origins of stone tool technology in Africa: a historical perspective. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 366, 1028–1037.

Delagnes, A., & Roche, H. (2005). Late Pliocene hominid knapping skills: the case of lokalalei 2C, west Turkana, Kenya. Journal of Human Evolution, 48, 435–472.

Durham, W. H. (1991). Coevolution: genes, culture, and human diversity. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Enquist, M., Ghirlanda, S., & Eriksson, K. (2011). Modelling the evolution and diversity of cumulative culture. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 366, 412–423.

Greenfield, P. M. (1991). Language, tools and brain: the ontogeny and phylogeny of hierarchically organized sequential behavior. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 14, 531–595.

Griffiths, T. L., Kalish, M. L., & Lewandowsky, S. (2008). Theoretical and empirical evidence for the impact of inductive biases on cultural evolution. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 363, 3503–3514.

Guerra-Filho, G., & Aloimonos, Y. (2012). The syntax of human actions and interactions. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 25, 500–514.

Heintz, C., Claidière, N., (2015). Current Darwinism in social science. In Lecointre G, Huneman P, Machery E, Silberstein M (Ed), Handbook of Evolutionary Thinking in the Sciences (pp 781–807). Dordrecht: Springer.

Hoppitt, W., & Laland, K. N. (2013). Social learning: an introduction to mechanisms, methods, and models. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Inizan, M.-L., Reduron-Ballinger, M., Roche, H., & Tixier, J. (1999). Technology and terminology of knapped stone. Nanterre: CREP.

Lashley, K. S. (1951). The problem of serial order in behavior. In L. A. Jeffress (Ed.), Cerebral mechanisms in behavior (pp. 112–136). New York: John Wyley & Sons.

Lewis, H. M., & Laland, K. N. (2012). Transmission fidelity is the key to the build-up of cumulative culture. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 367, 2171–2180.

Lombard, M., & Haidle, M. N. (2012). Thinking a Bow-and-arrow Set: cognitive implications of middle stone Age Bow and stone-tipped arrow technology. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 22(2), 237–264.

Lyman, R. L., & O’Brien, M. J. (2003). Cultural traits: units of analysis in early twentieth-century anthropology. Journal of Anthropological Research, 59, 225–250.

Mesoudi, A. (2011). Cultural evolution: how Darwinian theory can explain human culture and synthesize the social sciences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mesoudi, A., & O’Brien, M. J. (2008). The learning and transmission of hierarchical cultural recipes. Biological Theory, 3, 63–72.

Mesoudi, A., & O’Brien, M. J. (2009). Placing archaeology within a unified science of cultural evolution. In S. Shennan (Ed.), Pattern and process in cultural evolution (pp. 21–32). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Mesoudi, A., & Whiten, A. (2004). The hierarchical transformation of event knowledge in human cultural transmission. Journal of Cognition and Culture, 4, 1–24.

Mesoudi, A., Whiten, A., & Laland, K. N. (2006). Towards a unified science of cultural evolution. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 29, 329–383.

Miller, G. A., Galanter, E., & Pribam, K. H. (1960). Plans and structure of behavior. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc.

Moore, M. W. (2007). Lithic design space modelling and cognition in Homo floresiensis. In A. C. Schalley & D. Khlentzos (Eds.), Mental states (Evolution, function, nature, Vol. I, pp. 11–33). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Moore, M. W. (2010). “Grammar of action” and stone flaking design space. In A. Nowell & I. Davidson (Eds.), Stone tools and the evolution of human cognition (pp. 13–43). Boulder: University Press of Colorado.

Morin, O. (2016). How Traditions Live and Die. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Neff, H. (1992). Ceramics and evolution. Archaeological Method and Theory, 4, 141–193.

O’Brien, M. J., Lyman, R. L., Mesoudi, A., & VanPool, T. L. (2010). Cultural traits as units of analysis. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 365, 3797–3806.

Pastra, K., & Aloimonos, Y. (2012). The minimalist grammar of action. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 367, 103–117.

Pelegrin, J. (1990). Prehistoric lithic technology: some aspects of research. Archaeological Review from Cambridge, 9(1), 116–125.

Pelegrin, J. (1993). A framework for analyzing prehistoric stone tool manufacture and a tentative application to some early stones industries. In A. Berthelet & J. Chavaillon (Eds.), The use of tools by human and non-human primates (pp. 302–317). Oxford: Clarendon.

Pelegrin, J. (2005). Remarks about archaeological techniques and methods of knapping: elements of a cognitive approach to stone knapping. In V. Roux & B. Bril (Eds.), Stone knapping: the necessary conditions for a uniquely hominin behaviour (pp. 23–33). Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.

Perreault, C., Brantingham, P. J., Kuhn, S. L., Wurz, S., & Gao, X. (2013). Measuring the complexity of lithic technology. Current Anthropology, 54, S397–S406.

Reader, S. M. (2006). Evo-devo, modularity and evolvability: insights for cultural evolution. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 29, 361–362.

Richerson, P. J., & Boyd, R. (2005). Not by genes alone: how culture transformed human evolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Roux, V., & Bril, B. (Eds.). (2005). Stone knapping: the necessary conditions for a uniquely hominin behaviour. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.

Schank, R. C., & Abelson, R. P. (1977). Scripts, plans, goals, and understanding. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Schick, K., & Toth, N. (2006). An overview of the Oldowan industrial complex: the sites and the nature of their evidence. In N. Toth & K. Schick (Eds.), The Oldowan: case studies into the earliest stone Age (pp. 3–42). Gosport: Stone Age Institute Press.

Schlanger, N. (2005). The chaîne opératoire. In C. Renfrew & P. Bahn (Eds.), Archaeology: the Key concepts (pp. 18–23). London: Routledge.

Simon, H. A. (1962). The architecture of complexity. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 106(6), 467–482.

Soressi, M., & Geneste, J.-M. (2011). The history and efficacy of the chaîne opératoire approach to lithic analysis: studying techniques to reveal past societies in an evolutionary perspective. PaleoAnthropology, 334, 350.

Sperber, D. (1996). Explaining culture: a naturalistic approach. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Sperber, D. (2006). Why a deep understanding of cultural evolution is incompatible with shallow psychology. In N. J. Enfield & S. C. Levinson (Eds.), Roots of human sociality (pp. 431–449). Oxford: Berg.

Sperber, D., & Hirschfeld, L. A. (2004). The cognitive foundations of cultural stability and diversity. Trends in Cognitive Science, 8, 4046.

Sterelny, K. (2012). The evolved apprentice. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Stout, D. (2011). Stone toolmaking and the evolution of human culture and cognition. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 366, 1050–1059.

Stout, D., & Chaminade, T. (2009). Making tools and making sense: complex, intentional behaviour in human evolution. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 19(1), 85–96.

Stout, D., Toth, N., Schick, K., & Chaminade, T. (2008). Neural correlates of early Stone Age toolmaking: technology, language and cognition in human evolution. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 363, 1939–1949.

Whiten, A. (2002). Imitation of sequential and hierarchical structure in action: experimental studies with children and chimpanzees. In K. Dautenhahn & C. L. Nehaniv (Eds.), Imitation in animals and artifacts: complex adaptive systems (pp. 191–209). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Whittaker, J. C. (1994). Flintknapping: making and understanding stone tools. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Wimsatt, W. C. (2006). Generative entrenchment and an evolutionary developmental biology for culture. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 29, 364–366.

Wimsatt, W. C. (2013). Entrenchment and scaffolding: an architecture for a theory of cultural change. In L. Caporael, J. R. Griesemer, & W. C. Wimsatt (Eds.), Developing scaffolds in evolution, culture, and cognition (pp. 77–105). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Christophe Heintz, Olivier Morin, Mike O’Brien, and Dan Sperber for useful discussions and comments on the ideas presented here. The research reported in this manuscript was supported by the postdoctoral scholarship in technology studies of the Science Studies program at the Central European University and by the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007-2013) / ERC grant agreement n° [609819], SOMICS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Charbonneau, M. Modularity and Recombination in Technological Evolution. Philos. Technol. 29, 373–392 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-016-0228-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-016-0228-0