Abstract

Background and Purpose

We studied the hypothesized effects of changes in self-rated health (SRH) on subsequently assessed changes in the levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides (TRI), separately for men and women. We also investigated the reverse causation hypothesis, expecting the initial changes in the levels of serum lipids to predict subsequently assessed changes in SRH levels.

Methods

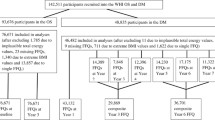

We used a longitudinal design and controlled for possible confounders known to be precursors of both SRH and the above three serum lipids. Participants were apparently healthy men (N = 846) and women (N = 378) who underwent a routine health check at three points of time (T1, T2, and T3); T1 and T3 were on the average 40 and 44 months apart for the men and women, respectively.

Results and Conclusions

For the men, relative to T1 SRH, an increase in T2 SRH was associated with an increase in the T3 HDL-C levels relative to T2 HDL-C and with a decrease in the T3 TRI levels relative to T2 TRI. For the women, initial changes in the SRH levels did not predict follow-up changes in either of the lipids. For both genders, the reverse causation hypothesis, expecting the T1–T2 change in each of the serum lipids to predict T2–T3 change in SRH, was not supported. For the men, there is support for the hypothesis that the effects of SRH on morbidity and mortality, found by past meta-analytic studies, could be mediated by serum lipids.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Barter P, Gotto AM, LaRosa JC, Maroni J, Szarek M, Grundy SM, et al. HDL-C cholesterol, very low levels of LDL-C cholesterol, and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(13):1301–10.

Bello N, Mosca L. Epidemiology of coronary heart disease in women. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2004;46(4):287–95.

Benyamini Y, Idler EL. Community studies reporting association between self-rated health and mortality- additional studies. Res Aging. 1999;21(3):392–401.

Benyamini Y, Leventhal EA, Leventhal H. Gender differences in processing information for making self-assessments of health. Psychosom Med. 2000;62(3):354–64.

Brissette I, Leventhal H, Leventhal EA. Observer ratings of health and sickness: can other people tell us anything about our health that we don’t know already? Health Psychol. 2003;22(5):471–8.

Brunner RL. Understanding gender factors affecting self-rated health. Gend Med. 2006;3(4):292–4.

Carroll MD, Lacher DA, Sorlie PD, Cleeman JI, Gordon DJ, Wolz M, et al. Trends in serum lipids and lipoproteins of adults, 1960–2002. JAMA. 2005;294(14):1773–81.

Deeg DJH, Kriegsman DMW. Concepts of self-rated health: specifying the gender difference in mortality risk. Gerontologist. 2003;43(3):376–86.

DeSalvo KB, Bloser N, Reynolds K, He J, Muntner P. Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question. A meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(3):267–75.

DeSalvo KB, Fan VS, McDonell MB, Fihn SD. Predicting mortality and healthcare utilization with a single question. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(4):1234–46.

Dobbins TA, Simpson JM, Oldenburg B, Owen N, Harris D. Who comes to a workplace health risk assessment? Int J Behav Med. 1998;5(4):323–34.

Domanski MJ. Primary prevention of coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(15):1543–5.

Dormann C. Modeling unmeasured third variables in longitudinal studies. Struct Equ Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2001;8(4):575–98.

Dowd JB, Zajacova A. Does the predictive power of self-rated health for subsequent mortality risk vary by socioeconomic status in the US? Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(6):1214–21.

Fenger M. Heritability and genetics of lipid metabolism. Future Lipidology. 2007;2(4):433–44.

Ferraro KF, Farmer MM, Wybraniec JA. Health trajectories: long-term dynamics among Black and White adults. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38(1):38–54.

Froom P, Melamed S, Triber I, Ratson NZ, Hermoni D. Predicting self-reported health: the CORDIS study. Prev Med. 2004;39(2):419–23.

Gilbody S, Richards D, Brealey S, Hewitt C. Screening for depression in medical settings with the patient health questionnaire (PHQ): a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(11):1596–602.

Goldman N, Glei DA, Chang M-C. The role of clinical risk factors in understanding self-rated health. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14(1):49–57.

Grundy SM. Promise of low-density lipoprotein-lowering therapy for primary and secondary prevention. Circulation. 2008;117(4):569–73.

Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and morbidity: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38 (1):21–37.

Ingelsson E, Schaefer EJ, Contois JH, McNamara JR, Sullivan LM, Keyes MJ, et al. Clinical utility of different lipid measures for prediction of coronary heart disease in men and women. JAMA. 2007;298(7):776–85.

Jylha M. What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(3):307–16.

Jylha M, Volpato S, Guralnik JM. Self-rated health showed a graded association with frequently used biomarkers in a large population sample. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(5):465–71.

Kaplan GA, Goldberg DE, Everson SA, Cohen RD, Salonen R, Tuomilehto J, et al. Perceived health status and morbidity and mortality: evidence from the Kuopio ischaemic heart disease risk factor study. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25(2):259–65.

Kawada T. Self-rated health and life prognosis. Arch Med Res. 2003;34(4):343–7.

Kosloski K, Stull DE, Kercher K, Van Dussen DJ. Longitudinal analysis of the reciprocal effects of s-assessed global health and depressive symptoms. J Gerontol B Psychological Sciences. 2005;60(6):296–303.

Kristenson M, Olsson AG, Kucinskiene Z. Good self-rated health is related to psychosocial resources and a strong cortisol response to acute stress: the LiVicordia Study of Middle-Aged Men. Int J Behav Med. 2005;12(3):153–60.

Manderbacka K, Lundberg O, Martikainen P. Do risk factors and health behaviours contribute to self-ratings of health? Soc Sci Med. 1999;48(12):1713–20.

Manly BFJ. Multivariate statistical methods: a primer. New York City: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2004.

Matthews KA. Are sociodemographic variables markers for psychological determinants of health? Health Psychol. 1989;8(6):641–8.

Mora PA, DiBonaventura M, Idler EL, Leventhal EA, Leventhal H. Psychological factors influencing self-assessments of health: toward an understanding of the mechanisms underlying how people rate their own health. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36(3):292–303.

Papakostas GI, Ongur D, Iosifescu DV, Mischoulon D, Fava M. Cholesterol in mood and anxiety disorders: review of the literature and new hypotheses. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004;14(2):135–42.

Pearlin LI, Lieberman MA, Menaghan EG, Mullan JT. The stress process. J Health Soc Behav. 1981;22(4):337–56.

Pollard TM, Schwartz JE. Are changes in blood pressure and total cholesterol related to changes in mood? An 18-month study of men and women. Health Psychol. 2003;22(1):47–53.

Okamoto K, Momose Y, Fujino A, Osawa Y. Gender differences in the relationship between self-rated health (SRH) and 6-year mortality risks among the elderly in Japan. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2008;47(3):311–7.

Roysamb E, Tambs K, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Neale MC, Harris JR. Happiness and health: Environmental and genetic contributions to the relationship between subjective well-being, perceived health, and somatic illness. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85(6):1136–46.

Shin JY, Suls J, Martin R. Are cholesterol and depression inversely related? A meta-analysis of the association between two cardiac risk factors. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36(1):33–43.

Shirom A, Toker S, Berliner S, Shapira I, Melamed S. The effects of physcial fitness and feeling vigorous on self-rated health. Health Psychol. 2008;27(5):567–75.

Shirom A, Westman M, Shamai O, Carel RS. Effects of work overload and burnout on cholesterol and triglycerides levels: the moderating effects of emotional reactivity among male and female employees. J Occup Health Psychol. 1997;2:275–88.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, the Patient Health Questionnaire Primary Care Study Group. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. J Am Med Assoc. 1999;282(18):1737–44.

Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K, Linzer M, de Gruy 3rd FV, Hahn SR, et al. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care. The PRIME-MD 1000 study. J Am Med Assoc. 1994;272(22):1749–56.

Steptoe A, Brydon L. Associations between acute lipid stress responses and fasting lipid levels 3 years later. Health Psychol. 2005;24(6):601–7.

Stoney CM, Bausserman L, Niaura R, Marcus B, Flynn M. Lipid reactivity to stress: II. Biological and behavioral influences. Health Psychol. 1999a;18(3):251–61.

Stoney CM, Niaura R, Bausserman L, Matacin M. Lipid reactivity to stress: I. Comparison of chronic and acute stress responses in middle-aged airline pilots. Health Psychol. 1999b;18(3):241–50.

Superko HR, King III S. Lipid management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a new strategy is required. Circulation. 2008;117(4):560–8.

Svedberg P, Bardage C, Sandin S, Pedersen NL. A prospective study of health, life-style and psychosocial predictors of self-rated health. Eur J Epidemiol. 2006;21(10):767–76.

Tirosh A, Rudich A, Shochat T, Tekes-Manova D, Israeli E, Henkin Y, et al. Changes in triglyceride levels and risk for coronary heart disease in young men. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(6):377–85.

Twisk JWR. Applied longitudinal data analysis of epidemiology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2003.

Unden AL, Elofsson S. Do different factors explain self-rated health in men and women? Gend Med. 2006;3(4):295–308.

Waldenstrom K, Ahlberg G, Bergman P, Forsell Y, Stoetzer U, Waldenstrom M, et al. Externally assessed psychosocial work characteristics and diagnoses of anxiety and depression. Occup Environ Med. 2008;65(2):90–6.

Wamala SP, Wolk A, Schenck-Gustafsson K, OrthGomer K. Lipid profile and socioeconomic status in healthy middle aged women in Sweden. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1997;51(4):400–7.

Weidner G, Boughal T, Connor SL, Pieper C, Mendell NR. Relationship of job strain to standard coronary risk factors and psychological characteristics in women and men of the family heart study. Health Psychol. 1997;16(3):239–47.

Zapf D, Dormann C, Frese M. Longitudinal studies in organizational stress research: a review of the literature with reference to methodological issues. J Occup Health Psychol. 1996;1(2):145–69.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This study was supported by a grant from the Israel Science Foundation; Grant 788/09.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shirom, A., Toker, S., Melamed, S. et al. The Relationships Between Self-Rated Health and Serum Lipids Across Time. Int.J. Behav. Med. 19, 73–81 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-011-9144-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-011-9144-y