Abstract

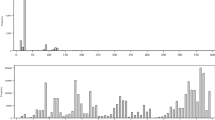

Lower-income citizens in the United States have distinct partisan and policy preferences from higher-income citizens. Lower-income citizens, however, have been numerically underrepresented in policymaking institutions throughout most of American history. This numerical underrepresentation of the working class is potentially problematic because members of Congress are consistently more responsive toward upper income constituents. This bias toward upper income constituents may be a result of the fact that members themselves are disproportionately wealthy. This paper seeks to determine what demographic relationships actually exist on the basis of legislator wealth. To ascertain this, we utilize data from Roll Call, which each year since 1990 has reviewed the financial disclosures of all 535 senators and representatives to determine the 50 richest members of Congress. For the first time, the report derived from forms covering 2014 went a step further by publishing a ranking of every single lawmaker by their minimum net worth. This analysis finds that there is not a straightforward relationship with legislator wealth and partisanship. There is, however, a strong relationships with race and legislative wealth. The wealthiest members of Congress tend to be disproportionately white Democrats and the least wealthy members non-whites. Along with being more likely to be white relatively wealthy members of Congress also tend to represent wealthier constituencies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Paul Burstein, American Public Opinion, Advocacy, and Policy in Congress: What the Public Wants and What it Gets (New York, Cambridge University Press, 2014), p. 59.

Rudy B. Andeweg and Jacques J.A. Thomassen, “Modes of Political Representation: Toward a New Typology,” Legislative Studies Quarterly 30 (2005): 507-528.

Jeffrey Harden, “Multidimensional Responsiveness: The Determinants of Legislators’ Representational Priorities,” Legislative Studies Quarterly 38 (2013): 155-184.

Gerhard Loewenberg, On Legislatures: The Puzzle of Representation (Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers, 2011), Chapter 1.

Peter K. Enns and Christopher Wlezien, “Group Opinion and the Study of Representation,” in Who Gets Represented (New York: Russell Sage, 2011), Peter Enns and Christopher Wlezien eds., pp. 1-25.

Nicholas Carnes, “Does the Numerical Underrepresentation of Working Class in Congress Matter?” Legislative Studies Quarterly 37 (2012): 5-34.

Ibid.

Nicholas Carnes. White Collar Government (Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 2013), p. 7.

Lisa Disch, “Democratic Representation and the Constituency Paradox,” Perspectives on Politics 10 (2012): 599-616.

Christopher Ellis, “Understanding Economic Biases in Representation: Income, Resources, and Policy Representation in the 110th House,” Political Research Quarterly 65 (2012): 938-951.

Roll Call, “Wealth of Congress Index,” http://media.cq.com/50Richest/ December 5, 2015.

Patrick Fisher, Demographic Gaps in American Political Behavior (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2014).

Sociologists for Women in Society, “Fact Sheet: Women and Wealth in the United States,” Spring 2010.

Roll Call, “Wealth of Congress Index.”

Ibid.

Sam Peltzman, “An Economic Interpretation of the History of Congressional Voting in the Twentieth Century,” American Economic Review 75 (1985): 656-675.

Larry Bartels, Unequal Democracy (New York: Russell Sage, 2008) and Thomas J. Hayes, “Responsiveness in an Era of Inequality: The Case of the U.S. Senate,” Political Research Quarterly 66 (2012): 585-599.

Nicholas Carnes. White Collar Government (Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 2013), p. 14.

Ibid.

Martin Gilens, “Preference Gaps and Inequality in Representation,” PS: Political Science and Politics 42 (2009): 335-341.

Martin Gilens and Benjamin I. Page, “Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens,” Perspectives on Politics 12 (2014): 565-581.

Jacob S. Hacker and Paul Pierson, “Winner-Take-All Politics: Public Policy, Political Organization, and the Precipitous Rise of Top Incomes in the United States,” Politics and Society 38 (2010): 152-204.

Nicholas Carnes. White Collar Government (Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 2013), p. 16.

Jeffrey A. Winters and Benjamin I. Page, “Oligarchy in the United States?” Perspectives on Politics 7 (2009): 731-751.

Peter K. Enns and Christopher Wlezien, “Group Opinion and the Study of Representation,” in Who Gets Represented (New York: Russell Sage, 2011), Peter Enns and Christopher Wlezien eds., pp. 1-25.

Thomas J. Hayes, “Responsiveness in an Era of Inequality: The Case of the U.S. Senate,” Political Research Quarterly 66 (2013): 585-599.

Larry Bartels, Unequal Democracy (New York: Russell Sage, 2008).

Gary Miller and Norman Schofield, “The Transformation of the Republican and Democratic Party Coalitions in the U.S.,” Perspectives on Politics 6 (2008): 433-450.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fisher, P. Demographic Dynamics of the Wealth Gap in Congress. Soc 53, 503–509 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-016-0057-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-016-0057-x