Abstract

There is an ambiguity in Amartya Sen’s capability approach as to what constitutes an individual’s resources, conversion factors and valuable functionings. What we here call the “circularity problem” points to the fact that all three concepts seem to be mutually endogenous and interdependent. To econometrically account for this entanglement we suggest a panel vector autoregression approach. We analyze the intertemporal interplay of the above factors over a time horizon of 15 years using the BHPS data set for Great Britain, measuring individual well-being in functionings space with a set of basic functionings, comprising “being happy”, “being healthy”, “being nourished”, “moving about freely”, “being well-sheltered” and “having satisfying social relations”. We find that there are indeed functionings that are resources for many other functionings (viz. “being happy”) while other functionings (“being well-sheltered” and “having satisfying social relations”) are by and large independent, thus shedding light on a facet of the capability approach that has been neglected so far.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It also extends to the question of whether some functionings might be considered indicators of capability and vice versa. We abstract from this question in the present paper and remain on the level of outcomes (functionings), not opportunities (capabilities to function).

We follow Kuklys (2005) in notation.

The survey is undertaken by the ESRC UK Longitudinal Studies Centre with the Institute for Social and Economic Research at the University of Essex, UK (BHPS 2009). Its aim is to track social and economic change in a representative sample of the British population (for more information on the data set, see Taylor 2009). The sample comprises about 15,000 individual interviews. Starting in 1991, up to now, there have been 17 waves of data collected with the aim of tracking the individuals of the first wave over time (there is a percentage of rotation as some individuals drop out of the sample over time and others are included, but attrition is quite low, see Taylor 2009).

This might also explain the finding by Ramos and Silber (2005) that the exact specification of a set of functionings does not seem overly critical for the resulting multidimensional welfare measure. The authors have demonstrated a great (empirical) similarity of the different approaches in their study (also using the BHPS data set).

We have relegated the descriptive statistics for model 2 in the appendix (see Table 5).

The BHPS also asks for individuals’ life satisfaction scores. We have decided against using these for two reasons. First, the question was only introduced halfway into the sampling period, resulting in considerably lower observations. While we could have included it for the shorter model, we wanted to keep the composition of the functionings in both models constant. Second, there seem to be order effects in the way the question was elicited in the survey, casting some doubt on the validity of the answers.

Note that we implicitly interpret our well-being measure as cardinal in using an OLS regression in the panel VAR (besides we use OLS for the income variables and continuous health, social and shelter variables in the models). This is justified for two reasons. First, such an interpretation is common in the psychological literature on well-being, and it has been shown that there are no substantial differences between both approaches in terms of the results they generate (Ferrer-i Carbonell and Frijters 2004): it seems that individuals convert ordinal response labels into similar numerical values such that these cardinal values equally divide up the response space (Praag 1991; Clark et al. 2008a). As opposed to this, the differences in results between model specifications that account for fixed effects and those which do not are substantial (Ferrer-i Carbonell and Frijters, 2004). Second, as our measure of well-being has 37 outcomes, the supposition of a cardinal underlying latent variable does not really seem problematic.

As in the case of well-being, we have reversed the numerical order of the Likert scale to consistently use higher values for higher ‘achievement’ in these domains. The original coding in the BHPS codes a value of one to be excellent health and five to be very poor health. Note further that in the 1999 wave, a different coding of this indicator has been used. Since comparability between the different scalings is nontrivial, we have chosen to discard the observations of this wave to have a more consistent panel at our disposal.

While we are aware of possible drawbacks of such a procedure, viz. neglecting parts of the variance inherent in the indicators, we feel justified on ignoring these concerns in the present context. The main aim of our paper lies elsewhere, and we allow ourselves to remain agnostic on the concrete aggregation of indicators. There is also some discussion in the literature to what extent a standard Principal Component Analysis provides flawed estimates for discrete proxy variables. This is based on the contention that a Pearson correlation matrix, as is used in a standard PCA, would not make much econometric sense when it comes to binary or ordinal variables, hence different types of variables necessitate different types of correlation matrices to be used in a PCA. We follow the reasoning of Kolenikov and Angeles (2009), who argue that this is unnecessary in the case of ordinal variables, especially when the number of ordinal categories is five or more. Empirically, there tend to be only small differences between using a PCA with polychoric correlations and just treating ordinal variables as cardinal in a PCA. We therefore did the calculations with a standard (Pearson) PCA.

In the first year, these expenditures were asked in continuous amounts of GBP, which could be easily transformed into these 12 categories by the authors, however.

See Table 7 in the appendix for more information on the housing conditions.

While (higher) education seems to play a role in the conversion of resources into functionings in many contexts, we are grateful to a referee for pointing out that this might not be the case for entrepreneurs or self-employed individuals.

For more information see (Taylor 2009), App. 2, pp. 18–19.

Moreover, the coding of this variable is arguably quite “crude” (Robeyns 2006, p. 256).

The other comparatively high correlation in that table is between education and age (r = −0.3424), two of our control variables of which we report only levels, not differences. An explanation why age is negatively associated with education could be that the sample contains a large proportion of older individuals who do not hold as many high academic degrees as might be usual today.

The low correlation (in levels) of log equivalised income with some of the other variables shows that these other dimensions of well-being do indeed capture important information on individuals’ well-being that cannot captured by income variables. Such low correlation also suggests that income might not be an important resource for many relevant other functionings (however, income and both food and mobility functionings show high positive correlation, of which at least the former correlation might be explained by the way we measure functioning achievement “being nourished”, i.e. via food expenditures).

Negative autocorrelation in differenced variables in VAR models has also been observed in other cases, such as firm growth (e.g. Coad 2010).

It is, however, still debated to what extent this set point might vary over long time horizons (Headey 2010).

One could speculate that this is an effect of “overachievement” in the food dimension, such as obesity, that then negatively impacts on individuals’ ability to earn their living, but this speculation is not borne out by the data as we can see no negative relation between food and health achievements.

The generally poor results in their case could of course be due to the coding of the variables or the shorter sample horizon, viz. fewer observations, which we cannot rule out completely.

We also conducted an analysis for the subgroup of unemployed but except for the negative autocorrelation of the individual functionings, no significant results were obtained. We attribute this to the relatively few individuals in this subgroup. In the short model for the unemployed, we only had 348 observations in differences.

References

Alkire, S. (2002). Valuing freedoms—Sen’s capability approach and poverty reduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Anand, P., & Hees, M. v. (2006). Capabilities and achievements: An empirical study. Journal of Socio-Economics, 35, 268–284.

Anand, P., Hunter, G., Carter, I., Dowding, K., Guala, F., & Hees, M. v. (2009). The development of capability indicators. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 10(1), 125–152.

Anand, P., Hunter, G., & Smith, R. (2005). Capabilities and well-being: Evidence based on the Sen-Nussbaum approach to welfare. Social Indicators Research, 74, 9–55.

Anand, P., Santos, C., & Smith, R. (2008). The measurement of capabilities. In: Basu, K., & Kanbur, R., (Eds.) Arguments for a better world: Essays in Honor of Amartya Sen (Vol. 1, Chap. 16 pp. 283–310). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Arrow, J. (1996). Estimating the influence of health as a risk factor on unemployment: A survival analysis of employment durations for workers surveyed in the German Socio-economic Panel (1984–1990). Social Science & Medicine, 42(12), 1651–1659.

Becchetti, L., Pelloni, A., & Rossetti, F. (2008). Relational goods, sociability, and happiness. Kyklos, 61(3), 343–363.

Becker, G. S. (1964). Human capital—A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. New York/London: Columbia University Press.

BHPS. (2009). British household panel survey. http://www.iser.essex.ac.uk/ulsc/bhps/.

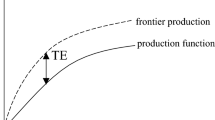

Binder, M., & Broekel, T. (2008). Applying a robust non-parametric efficiency analysis to measure conversion efficiency in Great Britain. SSRN working paper No. 1104430. Accepted for publication in: Journal of Human Development and Capabilities.

Binder, M., & Coad, A. (2010). An examination of the dynamics of happiness using vector autoregressions. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, forthcoming, doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2010.06.006

Brockmann, H., & Delhey, J. (2010). Introduction: The dynamics of happiness and the dynamics of happiness research. Social Indicators Research, 97, 1–5.

Burchardt, T. (2005). Are one man’s rags another man’s riches? Identifying adaptive expectations using panel data. Social Indicators Research, 74, 57–102.

Chiappero-Martinetti, E., & Salardi, P. (2007). Well-being process and conversion factors. An estimation of the micro-side of the well-being process. Mimeo.

Clark, A. E., Frijters, P., & Shields, M. A. (2008a). Relative income, happiness, and utility: An explanation for the Easterlin paradox and other puzzles. Journal of Economic Literature, 46(1), 95–144.

Clark, A. E., Diener, E., Georgellis, Y., & Lucas, R. E. (2008b). Lags and leads in life satisfaction: A test of the baseline hypothesis. The Economic Journal, 118, F222–F243.

Clark, A. E., & Oswald, A. J. (2002). A simple statistical method for measuring how life events affect happiness. International Journal of Epidemiology, 31, 1139–1144.

Coad, A. (2010). Exploring the processes of firm growth: Evidence from a vector auto-regression. Industrial and Corporate Change, forthcoming, doi:10.1093/icc/dtq018.

Cummins, R. A. (2000). Objective and subjective quality of life: An interactive model. Social Indicators Research, 52, 55–72.

Deutsch, J., Ramos, X., & Silber, J. (2003). Poverty and inequality of standard of living and quality of life in Great Britain. In M. J. Sirgy, D. Rahtz, & A. C. Samli (Eds.), Advances in quality-of-life theory and research (Chap. 7 pp. 99–128). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers

Diener, E., & Suh, E. (1997). Measuring quality of life: Economic, social, and subjective indicators. Social Indicators Research, 40, 189–216.

Diener, E., Suh, E., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin 125(2), 276–302.

Dolan, P., & White, M. (2006). Dynamic well-being: Connecting indicators of what people anticipate with indicators of what they experience. Social Indicators Research, 75, 303–333.

Easterlin, R. A. (2003). Explaining happiness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(19), 11176–11183.

Ferrer-i Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? The Economic Journal, 114, 641–659.

Frederick, S., & Loewenstein, G. F. (1999). Hedonic adaptation. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-Being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 302–329). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Gardner, J., & Oswald, A. (2004). How is mortality affected by money, marriage, and stress? Journal of Health Economics, 23, 1181–1207.

Gardner, J., & Oswald, A. J. (2007). Money and mental wellbeing: A longitudinal study of medium-sized lottery wins. Journal of Health Economics, 26, 49–60.

Graham, C., Eggers, A., & Sukhtankar, S. (2004). Does happiness pay? An exploration based on panel data from Russia. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 55, 319–342.

Grossman, M. (2005). Education and nonmarket outcomes. NBER working paper, no. 11582, http://www.nber.org/papers/w11582.

Headey, B. (2010). The set point theory of well-being has serious flaws: On the eve of a scientific revolution? Social Indicators Research, 97, 7–21.

Johnston, D. W., Propper, C., & Shields, M. A. (2009). Comparing subjective and objective measures of health: Evidence from hypertension for the income/health gradient. Journal of Health Economics, 28, 540–552.

Kolenikov, S., & Angeles, G. (2009). Socioeconomic status measurement with discrete proxy variables: Is principal component analysis a reliable answer? Review of Income and Wealth, 55(1), 128–165.

Kuklys, W. (2005). Amartya Sen’s capability approach—theoretical insights and empirical applications. Berlin: Springer

Lancaster, K. (1966). A new approach to consumer theory. Journal of Political Economy, 74(2), 132–157.

Lelli, S. (2001). Factor analysis vs. fuzzy sets theory: Assessing the influence of different techniques on Sen’s functioning approach. Center for economic studies discussion paper series 01.21.

Lelli, S. (2005). Using functionings to estimate equivalence scales. Review of Income and Wealth, 51(2), 255–284.

Levy, H., & Jenkins, S. P. (2008). Documentation for derived current and annual net household income variables, BHPS waves 1–16. Institute for Social and Economic Research, University of Essex, Colchester.

Lykken, D., & Tellegen, A. (1996). Happiness is a stochastic phenomenon. Psychological Science, 7(3), 186–189.

Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131(6), 803–855.

McClements, L. D. (1977). Equivalence scales for children. Journal of Public Economics, 8(2), 191–210.

Myers, D. G. (1999). Close relationships and quality of life. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-Being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 374–391). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Nussbaum, M. C. (2000). Women and human development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Oswald, A. J. (1997). Happiness and economic performance. The Economic Journal, 107(445), 1815–1831.

Praag, B. S. v. (1991). Ordinal and cardinal utility: An integration of the two dimensions of the welfare concept. Journal of Econometrics, 50(1–2), 69–89.

Qizilbash, M. (2002). Development, common foes and shared values. Review of Political Economy, 14(4), 463–480.

Ramos, X. (2008). Using efficiency analysis to measure individual well-being with an illustration for Catalonia. In N. Kakwani & J. Silber (Eds.), Quantitative approaches to multidimensional poverty measurement (Chap. 9 pp. 155–175). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

Ramos, X., & Silber, J. (2005). On the application of efficiency analysis to the study of the dimensions of human development. Review of Income and Wealth, 51(2), 285–309.

Robeyns, I. (2005). Selecting capabilities for quality of life measurement. Social Indicators Research, 74, 191–215.

Robeyns, I. (2006). Gender inequality in functionings and capabilities: Findings from the British household panel survey. In P. Bharati & M. Pal (Eds.), Gender disparity: Its manifestations, causes and implications (Chap. 13 pp. 236–277). Anmol, Delhi.

Roche, J. M. (2008). Monitoring inequality among social groups: A methodology combining fuzzy set theory and principal component analysis. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 9(3), 427–452.

Sen, A. K. (1984). Rights and capabilities. In Resources, Values and Development (pp. 307–324). Cambridge/Mass: Harvard University Press.

Sen, A. K. (1985a). Commodities and capabilities. Amsterdam: North Holland.

Sen, A. K. (1985b). Well-being, agency and freedom: The Dewey lectures 1984. The Journal of Philosophy, 82(4), 169–221.

Sen, A. K. (1992). Inequality reexamined. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Shields, M. A., & Wheatley Price, S. (2005). Exploring the economic and social determinants of psychological well-being and perceived social support in England. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (Statistics in Society), 168(3), 513–537.

Smith, J. P. (1999). Healthy bodies and thick wallets: The dual relation between health and economic status. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 13(2), 145–166.

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2008). Economic growth and subjective well-being: Reassessing the Easterlin paradox. NBER working paper no. 14282.

Taylor, M. F. E. (2009). British household panel survey user manual volume a: Introduction, technical report and appendices. In: J. Brice, N. Buck, & E. Prentice-Lane (Eds.), Colchester: University of Essex.

UNDP. (2006). Human development report. http://hdr.undp.org/hdr2006/report.cfm.

Zaidi, A., & Burchardt, T. (2005). Comparing incomes when needs differ: Equivalization for the extra costs of disability in the UK. Review of Income and Wealth, 51(1), 89–114.

Acknowledgment

We thank Tom Broekel and an anonymous referee for helpful comments and suggestions. Remaining errors are ours.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The authors are grateful for having been granted access to the BHPS data set, which was made available through the ESRC Data Archive. The data were originally collected by the ESRC Research Centre on Micro-Social Change at the University of Essex (now incorporated within the Institute for Social and Economic Research). Neither the original collectors of the data nor the Archive bear any responsibility for the analyses or interpretations presented here.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Binder, M., Coad, A. Disentangling the Circularity in Sen’s Capability Approach: An Analysis of the Co-Evolution of Functioning Achievement and Resources. Soc Indic Res 103, 327–355 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9714-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9714-4