Abstract

The problem of cooperation for rational actors comprises two sub problems: the problem of the intentional object (under what description does each actor perceive the situation?) and the problem of common knowledge for finite minds (how much belief iteration is required?). I will argue that subdoxastic signalling can solve the problem of the intentional object as long as this is confined to a simple coordination problem. In a more complex environment like an assurance game signals may become unreliable. Mutual beliefs can then bolster the earlier attained equilibrium. I will first address these two problems by means of an example, in order to draw some more general lessons about combining evolutionary theory and rationality later on.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Lewis (1969) is the seminal work regarding the statement of these problems in combination. See also Gilbert (1989), and see Radford (1969), Cargile (1970) on the problem of common knowledge for finite minds, and Heal (1978). Cubitt and Sugden (2003) is one noteworthy and fairly recent paper, also on both problems. The central question of their paper, however, is not about what the function of iterated mutual beliefs, what the relevant part of common knowledge, could be—something I will try to argue. We will get back to Lewis at the end of this paper.

The problem of the intentional object is of course a classic in analytic philosophy, with seminal work by Wittgenstein, Quine, Davidson, Kripke, Goodman.

Examples of bringing in parametric choice at an implausible (or unclear) point abound, to take a pick: Dupuy (1989), Gintis (2003), Vanderschraaff (2007) notes the trouble himself. Zollman (2005) also warns that one should be careful with drawing general lessons about human cooperation from very truncated models. Cf. the criticism by Sugden (2001).

See for example Henrich et al. (2004).

Albeit not in symmetric fashion. Escaping some actual teeth underway is more important than the problem of jumping up for nothing.

On a teleosemantic account of meaning, e.g. Millikan (1984, 1989). Of course teleosemantic theories of meaning, broadly construed, are not uncontroversial; but not, I suppose, for the restricted domain I am talking about here: primitive signals with an undisputed evolutionary past. Cf. Stegmann (2005).

Of course this plan of action is not unconditional, it depends on the other. Stag hunting, as I have supposed, is a cooperative project for our creatures. Then how might they ever get started? Stylized, the hunt might be preceded by a two-stage trigger. A) The presence of a stag plus the presence of a comrade in my vicinity causes a half way house ‘stag-as-prey’ action tendency and the corresponding signal in me. B) If this also happens in you, then you transmit the ‘stag-as-prey’ signal to me, and this brings closure, the final confirmation I need: now I am all ready to go. Compare Velleman’s analysis of a shared intention between two individuals (Velleman 1997). It is questionable whether Velleman succeeds because he discusses conditional intentions between rational actors. The crucial point here is that the cooperative project at this stage can be understood in purely causal, subdoxastic, terms.

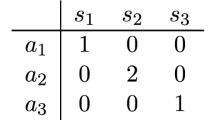

In the other subdivision of the stag hunt game [rabbits, rabbits] has the same pay off as [rabbits, stag] and v.v.

For an overview see Devetag and Ortmann (2007).

A repeated game with a small set of players and no anonymity can also generate the Pareto dominant outcome, but this result quickly unravels with more players and anonymity. Therefore the focus in the literature on randomized series, these make up the challenge.

For a recent restatement see Zahavi (2003).

One could object here that this adding costs for one party alters the pay-offs of our original game, as these are supposed to be net figures, benefits minus costs. But why should that matter? The cause of this change in pay-off structure could simply be a relevant fact. There is no rule that says that an analysis of a history of interaction should restrict itself to one and only one game form from beginning to end.

See the literature mentioned in note 5.

For an overview see Searcy and Nowicki (2005).

Møller (1990).

Wheeler (2009).

For references see Searcy and Nowicki (2005, pp. 75, 76).

Couldn’t it all be accounted for in terms of conditioned response? See Sect. 4.

This has a foothold in the literature on the origins of human intelligence: what is known as the Machiavellian intelligence hypothesis. Scholars who wonder about the evolutionary development of human intelligence focus on deception. Social animals benefit from group life, from economies of scale, division of labour, and cooperative work. But social life also brings various sources of conflict amongst the individuals: over food, mating access, who bosses whom, who are allies, and so on. These intricacies imply that it becomes more and more important to have in mind not only what others are doing, and what they might be up to, but also what they think: beliefs about beliefs, in other words. In this field, tactical deception has become a paradigm for demonstrating such higher order beliefs. It has become a standard for cognitive performance in comparative psychology. Seminal work is Byrne and Whiten (1988) and Dunbar (2003). Cf. Sterelny (2006). In line with this, note that the stag hunt story has now moved beyond Homo Habilis.

To be fair, Zollman is aware of this problem (see note 4).

Unfortunately, Duffy and Feltovich (2006), while relating to Aumann’s work (in Duffy and Feltovich 2002), did not choose a stag hunt of the assurance type. They did, however, compare a simple stag hunt with a chicken game and a prisoner’s dilemma. The trends in the results with the simple stag hunt and the PD are such that I think it is safe to interpolate: what is true of both their stag hunt and their PD is arguably true of an assurance stag hunt too.

The laboratory context is of course different than our imagined stag hunt story but I submit that the relevant relationship between signalling and mutual beliefs, i.e. how these mechanisms work together, is similar.

Compare on the origin of convention Cubitt and Sugden (2003: 203) remarking that in the end “at least some inductive standards could be common,” for example certain “innate tendencies to privilege certain patterns when making inductive inferences,” with such tendencies then of course being the product of an evolutionary process.

I assume here that forgetfulness includes such failure of conditioned learning.

See Cubitt and Sugden (2003) on how this structure could be generated.

Compare Sillari (2005) for a formal answer. Which portion of the infinite structure that becomes actual, Sillari says, has to do with what is deemed irrelevant, or what cannot be handled for lack of computational power, or for psychological reasons, and so on. He then develops a tool, ‘awareness structures,’ to take formally account of such heuristics. My approach is different but could be regarded as contrastive: given a subdoxastic basis, what could be, not irrelevant, but exactly relevant for mutual belief iteration, what could be grounds for ascending in the common knowledge structure.

Some theoretical possibilities, not mutually exclusive: signals are products of trial and error learning (evolutionary game theory applies), signals are replicators and units of selection (memetics), a teleological theory of meaning restricted to more or less simple signals (cf. Sterelny 1990).

References

Aumann R (1990) Nash equilibria are not self-enforcing. In: Gabszewicz J, Richard J, Wolsey L (eds) Economic decision making, games, econometrics and optimization. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Binmore K (2008) Do conventions need to be common knowledge? Topoi 27:17–27

Brosig J (2002) Identifying cooperative behavior: some experimental results in a prisoner’s dilemma game. J Econ Behav Organ 47:275–290

Byrne R, Whiten A (eds) (1988) Machiavellian intelligence: social expertise and the evolution of intellect in monkeys, apes, and humans. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Call J, Tomasello M (2008) Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? 30 years later. Trends Cogn Sci 12:187–192

Cargile J (1970) A note on “iterated knowings”. Analysis 30:151–155

Charness G (2000) Self-serving cheap talk: a test of Aumann’s conjecture. Games Econ Behav 33:177–194

Clark K, Kay S, Sefton M (2001) When are Nash equilibria self-enforcing? An experimental analysis. Int J Game Theory 29:495–515

Connor R, Mann J (2006) Social cognition in the wild: Machiavellian Dolphins? In: Hurley S, Nudds M (eds) Animal rationality?. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Cubitt R, Sugden R (2003) Common knowledge, salience and convention: a reconstruction of David Lewis’ game theory. Econ Philos 19:175–210

Davidson D (1982) Rational animals. Dialectica 36:317–327

Devetag G, Ortmann A (2007) When and why? A critical survey on coordination failure in the laboratory. Exp Econ 10:331–344

Duffy J, Feltovich N (2002) Do actions speak louder than words? An experimental comparison of observation and cheap talk. Games Econ Behav 39:1–27

Duffy J, Feltovich N (2006) Words, deeds, and lies: strategic behaviour in games with multiple signals. Rev Econ Stud 73:669–688

Dunbar R (2003) Evolution of the social brain. Science 302:1160–1161

Dupuy J (1989) Common knowledge, common sense. Theory Decis 27:37–62

Eilan N, Hoerl C, McCormack T, Roessler J (eds) (2005) Joint attention: communication and other minds. Oxford University Press, New York

Ekman P (1971) Telling lies. W.W. Norton, New York

Ekman P (2003) Emotions revealed. Henri Holt, New York

Ekman P, Friessen W (1971) Constants across cultures in the face and emotion. J Pers Soc Psychol 17:124–129

Fine A (1993) Fictionalism. Midwest Stud Philos 18:1–18

Fine A (2009) Science fictions: comment on Godfrey-Smith. Philos Stud 143:117–125

Frank R (1988) Passions within reason: the strategic role of the emotions. W.N. Norton, New York

Frank R (2004) Can cooperators find one another? In: What price the moral high ground? Ethical dilemmas in competitive environments. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Frigg R (2010) Models and fiction. Synthese 172:251–268

Gilbert M (1989) Rationality and salience. Philos Stud 57:61–77

Gintis H (2003) Solving the puzzle of human sociality. Ration Soc 15:155–187

Gintis H (2007) A framework for the unification of the behavioral sciences. Behav Brain Sci 30:1–61

Godfrey-Smith P (2009) Models and fictions in science. Philos Stud 143:101–116

Guala F (2012) Reciprocity: weak or strong? What punishment experiments do (and do not) demonstrate. Behav Brain Sci 35:1–59

Heal J (1978) Common knowledge. Philos Q 28:116–131

Henrich J, Boyd R, Bowles S, Camerer C, Fehr E, Gintis H (eds) (2004) Foundations of human sociality: economic experiments and ethnographic evidence from fifteen small-scale societies. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Lewis D (1969) Convention. A Philosophical Study. Basil Blackwell, Oxford

Millikan R (1984) Language, thought, and other biological categories. MIT Press, Cambridge

Millikan R (1989) Biosemantics. J Philos 6:281–297

Møller A (1990) Deceptive use of alarm calls by male swallows, Hirundo rustica: a new paternity guard. Behav Ecol 1:1–6

Morgan M (2001) Models, stories, and the economic world. J Econ Methodol 8:361–384

Morgan M (2004) Imagination and imaging in model building. Philos Sci 71:753–766

Povinelli D, Vonk J (2006) We don’t need a microscope to explore the chimpanzee’s mind. In: Hurley S, Nudds M (eds) Animal rationality?. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 385–412

Radford C (1969) Knowing and telling. Philos Rev 78:326–336

Sally D (1995) Conversation and cooperation in social dilemmas: a meta-analysis of experiments from 1958 to 1992. Ration Soc 7:58–92

Searcy W, Nowicki S (2005) The evolution of animal communication. Reliability and deception in signaling systems. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Sillari G (2005) A logical framework for convention. Synthese 147:379–400

Skyrms B (2004) The stag hunt and the evolution of social structure. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Skyrms B (2010) Signals. Evolution, learning and information. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Stegmann U (2005) John Maynard Smith’s notion of animal signals. Biol Philos 20:1011–1025

Sterelny K (1990) The representational theory of mind: an introduction. Blackwell, Cambridge

Sterelny K (2006) Folk logic and animal rationality. In: Hurley S, Nudds M (eds) Animal rationality?. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 293–311

Sugden R (2000) Credible worlds: the status of theoretical models in economics. J Econ Methodol 7:1–31

Sugden R (2001) The evolutionary turn in game theory. J Econ Methodol 8:113–130

Sugden R (2009) Credible worlds, capacities, and mechanisms. Erkenntnis 70:3–27

Tomasello M, Call J (1997) Primate cognition. Oxford University Press, New York

Tomasello M, Call J (2006) Do chimpanzees know what others see—or only what they are looking at? In: Hurley S, Nudds M (eds) Animal rationality?. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 371–384

Tomasello M, Call J, Hare B (2003) Chimpanzees understand psychological states—the question is which ones and to what extent. Trends Cognit Sci 7:153–156

Tomasello M, Carpenter M, Call J, Behne T, Moll H (2005) Understanding and sharing of intentions: the origins of cultural cognition. Behav Brain Sci 28(2005):675–735

van Hooff J (1972) A comparative approach to the phylogeny of laughter and smiling. In: Hinde R (ed) Non-verbal communication. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

van Hooff J, Preuschoft S (2003) Laughter and smiling: the intertwining of nature and culture. In: de Waal F, Tyack P (eds) Animal social complexity. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Vanderschraaff P (2007) Covenants and reputations. Synthese 157:155–183

Velleman J (1997) How to share an intention. Philos Phenomenol Res 57:29–50

Wheeler B (2009) Monkeys crying wolf? Tufted capuchin monkeys use anti-predator calls to usurp resources from conspecifics. Proc Royal Soc 276:3013–3018

Zahavi A (2003) Indirect selection and individual selection in sociobiology: my personal views on theories of social behaviour’ (anniversary essay). Anim Behav 65:859–863

Zollman K (2005) Talking to neighbors: the evolution of regional meaning. Philos Sci 72:69–85

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Govert den Hartogh and Gijs van Donselaar.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Boer, J. A stag hunt with signalling and mutual beliefs. Biol Philos 28, 559–576 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10539-013-9375-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10539-013-9375-1