Abstract

Purpose

The active form of vitamin D (1,25(OH)2D) contributes to blood flow regulation in skeletal muscle. The aim of the present study was to determine whether this hormone also modulates coronary physiology, and thus whether abnormalities in its bioavailability contribute to excess cardiovascular risk in patients with disorders of mineral metabolism.

Methods

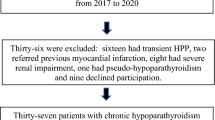

As a clinical model of the wide variability in 1,25(OH)2D bioavailability, we studied 23 patients (62 ± 8 years) with suspected primary hyperparathyroidism referred for myocardial perfusion imaging because of atypical chest pain and at least one cardiovascular risk factor. Dipyridamole and baseline myocardial blood flow indexes were assessed on G-SPECT imaging of 99mTc-tetrofosmin, with normalization of the myocardial count rate to the corresponding first-transit counts in the pulmonary artery. Coronary flow reserve (CFR) was defined as the ratio between dipyridamole and baseline myocardial blood flow indexes. In all patients, parathyroid hormone, 25-hydroxy vitamin D (25(OH)D) and 1,25(OH)2D serum levels were determined.

Results

Primary hyperparathyroidism was eventually diagnosed in 15 of the 23 patients. The mean 25(OH)D concentration was relatively low (21 ± 10 ng/mL) while the concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D varied widely but within the normal range (mean 95 ± 61 pmol/L). No patient showed reversible perfusion defects on G-SPECT. CFR was not correlated with either the serum concentration of 25(OH)D nor that of parathyroid hormone, but was strictly correlated with the serum level of 1,25(OH)2D (R = 0.8, p < 0.01). Moreover, patients with a 1,25(OH)2D concentration below the median value (86 pmol/L) had markedly lower CFR than the other patients (1.48 ± 0.40 vs. 2.51 ± 0.63, respectively; p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Bioavailable 1,25(OH)2D modulates coronary microvascular function. This effect might contribute to the high cardiovascular risk of conditions characterized by chronic reduction in bioavailability of this hormone.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Lavie CJ, Lee JH, MIlani RV. Vitamin D and cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1547–56.

Holick MF. Vitamin D, for health and in chronic kidney disease. Semin Dial. 2005;18:266–75.

Anderson JL, May HT, Horne BD, Bair TL, Hall NL, Carlquist JF, et al.; Intermountain Heart Collaborative (IHC) Study Group. Relation of vitamin D deficiency to cardiovascular risk factors, disease status, and incident events in a general healthcare population. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:963–8.

Pittas AG, Chung M, Trikalinos T, Mitri J, Brendel M, Patel K, et al. Systematic review: vitamin D and cardiometabolic outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:307–14.

Pilz S, Dobnig H, Fischer JE, Wellnitz B, Seelhorst U, Boehm BO, et al. Low vitamin D levels predict stroke in patients referred to coronary angiography. Stroke. 2008;39:2611–3.

Deo R, Katz R, Shlipak MG, Sotoodehnia N, Psaty BM, Sarnak MJ, et al. Vitamin D, parathyroid hormone, and sudden cardiac death: results from the cardiovascular health study. Hypertension. 2011;58:1021–8.

Borges AC, Feres T, Vianna LM, Paiva TB. Effect of cholecalciferol treatment on the relaxant responses of spontaneously hypertensive rat arteries to acetylcholine. Hypertension. 1999;34:897–901.

Artham SM, Lavie CJ, Milani RV, Patel DA, Verma A, Ventura HO. Clinical impact of left ventricular hypertrophy and implications for regression. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;52:153–67.

Duprez D, de Buyzere M, de Backer T, Clement D. Relationship between vitamin D3 and the peripheral circulation in moderate arterial primary hypertension. Blood Press. 1994;3:389–93.

Molinari C, Uberti F, Grossini E, Vacca G, Carda S, Invernizzi M, et al. 1α,25-Dihydroxycholecalciferol induces nitric oxide production in cultured endothelial cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2011;27:661–8.

Shapses SA, Manson JE. Vitamin D and prevention of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: why the evidence falls short. JAMA. 2011;305:2565–6.

Elamin MB, Nisrin O, Abu E, Fatourechi MM, Alkatib AA, Almandoz JP, et al. Vitamin D and cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1931–42.

Hewison M, Zehnder D, Bland R, Stewart PM. 1alpha-Hydroxylase and the action of vitamin D. J Mol Endocrinol. 2000;25:141–8.

Jourde-Chiche N, Dou L, Cerini C, Dignat-George F, Brunet P. Vascular incompetence in dialysis patients: protein-bound uremic toxins and endothelial dysfunction. Semin Dial. 2011;24:327–37.

Marini C, Giusti M, Armonino R, Ghigliotti G, Bezante G, Vera L, et al. Reduced coronary flow reserve in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism: a study by G-SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:2256–63.

Ito Y, Katoh C, Noriyasu K, Kuge Y, Furuyama H, Morita K, et al. Estimation of myocardial blood flow and myocardial flow reserve by 99mTc-sestamibi imaging: comparison with the results of [15O]H2O PET. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30:281–7.

Taki J, Fujino S, Nakajima K, Matsunari I, Okazaki H, Saga T, et al. (99m)Tc-sestamibi retention characteristics during pharmacologic hyperemia in human myocardium: comparison with coronary flow reserve measured by Doppler flowire. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:1457–63.

Storto G, Cirillo P, Vicario ML, Pellegrino T, Sorrentino AR, Petretta M, et al. Estimation of coronary flow reserve by Tc-99m sestamibi imaging in patients with coronary artery disease: comparison with the results of intracoronary Doppler technique. J Nucl Cardiol. 2004;11:682–8.

Storto G, Sorrentino AR, Pellegrino T, Liuzzi R, Petretta M, Cuocolo A. Assessment of coronary flow reserve by sestamibi imaging in patients with typical chest pain and normal coronary arteries. Eur J Nucl Med. 2007;34:1156–61.

Marini C, Bezante G, Gandolfo P, Modonesi E, Morbelli SD, Depascale A, et al. Optimization of flow reserve measurement using SPECT technology to evaluate the determinants of coronary microvascular dysfunction in diabetes. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:357–67.

Daniele S, Nappi C, Acampa W, Storto G, Pellegrino T, Ricci F, et al. Incremental prognostic value of coronary flow reserve assessed with single-photon emission computed tomography. J Nucl Cardiol. 2011;18:612–9.

Hendel RC, Budoff MJ, Cardella JF, Chambers CE, Dent JM, Fitzgerald DM, et al.; American College of Cardiology (ACC); American Heart Association (AHA). ACC/AHA/ACR/ASE/ASNC/HRS/NASCI/RSNA/SAIP/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR/SIR. Key Data Elements and Definitions for Cardiac Imaging: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Writing Committee to Develop Clinical Data Standards for Cardiac Imaging). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:91–124.

Camici P, Marraccini P, Marzilli M, Lorenzoni R, Buzzigoli G, Puntoni R, et al. Coronary hemodynamics and myocardial metabolism during and after pacing stress in normal humans. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:E309–17.

Scragg R. Seasonality of cardiovascular disease mortality and the possible protective effect of ultra-violet radiation. Int J Epidemiol. 1981;10:337–41.

Fleck A. Latitude and ischaemic heart disease. Lancet. 1989;1:613.

Kendrick J, Targher G, Smits G, Chonchol M. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D deficiency is independently associated with cardiovascular disease in the third national health and nutrition examination survey. Atherosclerosis. 2009;205:255–60.

Kasuga H, Hosogane N, Matsuoka K, Mori I, Sakura Y, Shimakawa K, et al. Characterization of transgenic rats constitutively expressing vitamin D-24-hydroxylase gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;297:1332–8.

Shen H, Bielak FL, Ferguson JF, Streeten EA, Yerges-Armstrong LM, Liu J, et al. Association of the vitamin D metabolism gene CYP24A1 with coronary artery calcification. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:2648–54.

Watson KE, Abrolat ML, Malone LL, Hoeg JM, Doherty T, Detrano R, et al. Active serum vitamin D levels are inversely correlated with coronary calcification. Circulation. 1997;96:1755–60.

Young KA, Snell-Bergeon JK, Naik RG, Hokanson JE, Tarullo D, Gottlieb PA, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and coronary artery calcification in subjects with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:454–8.

Gould KL, Lipscomb K. Effects of coronary stenoses on coronary flow reserve and resistance. Am J Cardiol. 1974;34:48–55.

Kim C, Kwok Y, Heagerty P, Redberg R. Pharmacologic stress testing for coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2001;146:934–43.

Travain MI, Wexler JP. Pharmacological stress testing. Semin Nucl Med. 1999;29:298–318.

Koleganova N, Piecha G, Ritz E, Gross ML. Calcitriol ameliorates capillary deficit and fibrosis of the heart in subtotally nephrectomized rats. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:778–87.

Parodi O, Neglia D, Palombo C, Sambuceti G, Giorgetti A, Marabotti C, et al. Comparative effects of enalapril and verapamil on myocardial blood flow in systemic hypertension. Circulation. 1997;96:864–73.

Möser GH, Schrader J, Deussen A. Turnover of adenosine in plasma of human and dog blood. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:C799–806.

Chilian WM, Layne SM, Klausner EC, Eastham CL, Marcus ML. Redistribution of coronary microvascular resistance produced by dipyridamole. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:H383–90.

Sambuceti G, Marzilli M, Marini C, L'Abbate A. Interaction between coronary artery stenosis and coronary microcirculation in ischemic heart disease. Z Kardiol. 2000;89(IX):126–31.

Sambuceti G, Marzilli M, Mari A, Marini C, Schluter M, Testa R, et al. Coronary microcirculatory vasoconstriction is heterogeneously distributed in acutely ischemic myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288(5):H2298–305.

Raitakari OT, Toikka JO, Laine H, Ahotupa M, Iida H, Viikari JS, et al. Reduced myocardial flow reserve relates to increased carotid intima-media thickness in healthy young men. Atherosclerosis. 2001;156:469–75.

Kaufmann PA, Gnecchi-Ruscone T, di Terlizzi M, Schäfers KP, Lüscher TF, Camici PG. Coronary heart disease in smokers: vitamin C restores coronary microcirculatory function. Circulation. 2000;102:1233–8.

Sambuceti G, Marzullo P, Giorgetti A, Neglia D, Marzilli M, Salvadori P, et al. Global alteration in perfusion response to increasing oxygen consumption in patients with single-vessel coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1994;90:1696–705.

Scragg RK, Camargo Jr CA, Simpson R. Relation of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D to heart rate and cardiac work (from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys). Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:122–8.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to dr. Paolo Bruzzi for valuable assistance in the statistical analysis. The study was supported by the following public bodies: Italian Ministry of Health (Finanziamento conto capitale 2012) and by Regione Liguria (Finanziamento ricerca sanitaria 2009).

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Capitanio, S., Sambuceti, G., Giusti, M. et al. 1,25-Dihydroxy vitamin D and coronary microvascular function. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 40, 280–289 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-012-2271-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-012-2271-0