Abstract

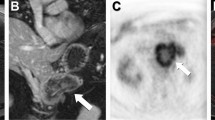

Objective: To assess the usefulness of 2-[fluorine-18]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) in locating occult primary lesions.Methods: 50 patients with varying heterogeneous metastases of unknown primary origin were referred for FDG PET. The locations of the known metastatic tumor manifestations were distributed as follows: cervical lymph nodes metastases (n=18), skeletal metastases (n=15), cerebral metastases (n=12), others (n=5). All patients underwent whole body18F-FDG PET imaging. The images were interpreted by visual inspection and semi-quantitative analysis (standardized uptake value, SUV). The patients had undergone conventional imaging within 2 weeks of FDG PET. Surgical, clinical and histopathologic findings were used to assess the performance of FDG PET.Results: FDG PET was able to detect the location of the primary tumor in 32/50 patients (64%). The primary tumors were proved by histopathologic results, and located in the lungs (n=17), the nasopharynx (n=9), the breast (n=2), the ovary (n=1), the colon (n=1), the prostate (n=1), the thyroid (n=1). FDG PET were proved false positive in 2 patients (4%), and the suspicious primary tumors were in uterus and colon respectively. During the clinical follow-up of 2 to 26 months, the primary tumor was found in only 2 patients (prostate cancer, gastric cancer).Conclusion: PET imaging allows identification of the primary site and metastatic lesions(including bone and soft tissue metastases) at a single examination. Whole body18F-FDG PET allows effective localization of the unknown primary site of origin and can contribute substantially to patient care.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Davidson BJ, Spiro RH, Patel S,et al. Cervical metastases of occult origin: the impact of combined modality therapy. Am J Surg, 1994, 168: 395–399.

Muir C. Cancer of unknown primary site. Cancer, 1995, 75: 353–356.

Hainsworth JD, Greco FA. Treatment of patients with cancer of an unknown primary site. N Engl J Med, 1993, 329: 257–263.

Maiche AG. Cancer of unknown primary: a retrospective study based on 109 patients. Am J Clin Oncol, 1993, 16: 26–29.

Harwick RD. Cervical metastases from an occult primary site. Semin Surg Oncol, 1991, 7: 2–8.

Riquet M, Badoual C, Barthes F,et al. Metastatic thoracic lymph node carcinoma with unknown primary site. Ann Thorac Surg, 2003, 75: 244–249.

De Braud F, Heilbrun LK, Ahmed K,et al. Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of an unknown primary localized to the neck: advantages of an aggressive treatment. Cancer, 1989, 64: 510–515.

Bar-Shalom R, Valdivia AY, Blaufox MD. PET imaging in oncology. Semin Nucl Med, 2000, 30: 150–185.

Hoh CK, Schiepers C, Seltzer MA,et al. PET in oncology: will it replace the other modalities? Semin Nucl Med, 1997, 27: 94–106.

Gambhir SS, Czernin J, Schwinmmeer J,et al. A tabulated summary of the FDG PET. J Nucl Med, 2000, 42: 1s-93s.

Reske SN, Kotzerke J. FDG-PET for clinical use. Eur J Nucl Med, 2001, 28: 1707–1723.

Coleman RE. Newsline. J Nucl Med, 2000, 41: 36–42.

Braams JW, Pruim J, Kole AC,et al. Detection of unknown primary head and neck tumors by positron emission tomography. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 1997, 26: 112–115.

Bohuslavizki KH, Klutmann S, Kroger S,et al. FDG PET detection of unknown primary tumors. J Nucl Med, 2000, 41: 816–822.

Kole AC, Nieweg OE, Pruim J,et al. Detection of unknown occult primary tumors using positron emission tomography. Cancer, 1998, 82: 1160–1166.

Aassar OS, Fischbein NJ, Caputo GR,et al. Metastatic head and neck cancer: role and usefulness of FDG PET in locating occult primary tumors. Radiology, 1999, 210: 177–181.

Regelink G, Brouwer J, Bree RD,et al. Detection of unknown primary tumours and distant metastases in patients with cervical metastases: value of FDG PET versus conventional modalities. Eur J Nucl Med, 2002, 29: 1024–1030.

Padgett HC, Schmidt DG, Luxen A,et al. Computer-controlled radiochemical synthesis: a chemistry process control unit for the automated production of radiochemicals. Appl Radiat Isot, 1989, 40: 433–445.

Smith TAD. FDG uptake, tumour characteristics, and response to therapy: a review. Nucl Med Commun, 1998, 19: 97–105.

Jeong HJ, Chung JK, Kim YK,et al. Usefulness of whole-body18F-FDG PET in patients with suspected metastatic brain tumors. J Nucl Med, 2002, 43: 1432–1437.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jun, Z., Xiangtong, L., Yihui, G. et al. Detection of unknown primary tumors using whole body FDG PET. Chin. -Ger. J. Clin. Oncol. 2, 179–183 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02842297

Received:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02842297