Abstract

This section presents lessons learnt from Thailand in climate policy design. Thailand has filled the gap between modelling analyses and climate policy development in its Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Action (NAMA). Thailand’s mitigation pledge under NAMA framework was successfully designed and communicated to UNFCCC in COP20. The integrated assessment modelling analysis plays an important role in the development of Thailand NAMA. Consensus building was derived from several discussions among stakeholders of NAMA implementation. Criteria for selection of greenhouse gas countermeasures were based on cost optimization by using a module of the Asia-Pacific Integrated Model called ‘AIM/Enduse’, abatement costs, co-benefits and feasibility of implementation. In addition, economic feasibility of countermeasures in NAMA actions was also assessed. Then, NAMA implementation has been prepared based on assumptions concerning limitations of resources, capital requirement, timing and appropriateness for Thailand.

Since 2012 Thailand’s mitigation pledge to UNFCCC has been prepared on the basis of domestic appropriate measures. Co-benefits of NAMAs are also assessed, and they reveal positive aspects of GHG mitigation under NAMA framework. Results found that Thailand has high potential of GHG emission reduction by both domestically supported NAMAs and internationally supported NAMAs about 23–73 million tonnes CO2 per year in 2020 or approximately accounted for 7–20 % in 2020 of the total GHG emissions. The NAMA actions include measures in (1) renewable electricity, (2) energy efficiency, (3) biofuels in transportation and (4) environmental sustainable transport system. These GHG countermeasures are in line with the national policy and plans of ministries of energy and transport in order to avoid the conflict between climate policy and policies of the related ministries. Results of cost optimization, co-benefits, economics and appropriateness are also necessary for communication among policymakers, administrators, academic researchers and the public on consensus building.

Finally, to ensure the quantified GHG reduction in 2020 and the transparency of Thailand’s NAMA implementation, the measurement reporting and verification (MRV) process is required. The MRV process of these NAMAs needs cooperation among related ministries. These lessons learnt from Thailand, when modified as needed, can be a ‘good practice’ of climate policy design.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Thailand NAMA

- Integrated assessment modelling

- Renewable energy

- Energy efficiency

- Co-benefits of GHG Mitigation

- AIM/Enduse

-

Thailand successfully developed its Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Action (NAMA).

-

Integrated assessment modelling helps in climate policy development.

-

Consensus building is necessary among stakeholders’ concerns.

Lessons learnt from Thailand can be a ‘good practice’ of climate policy design.

1 Introduction

Within the climate change framework, there is a gap between modelling analyses and policy development, and whether national climate policy incorporates such modelling analyses depends on several factors. This section introduces a good example of a means to fill in this gap. Through discussion with the climate change focal point and related agencies, Thailand succeeded in reflecting the modelling analysis in actual policy development. Thailand’s scenario studies on Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Action (NAMA) and NAMA roadmap development have been highly successful. This approach can be adopted by other regions as a ‘good practice’ of climate policy design and modified as needed according to local conditions.

2 NAMA and CO2 Mitigation Strategy

Climate change and greenhouse gas (GHG) mitigation are two key global issues, with a growing list of countries adding them to agendas within United Nation Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) discussions. Further, the Conference of Parties (COP) has decided on appropriate implementations and GHG mitigation targets for developing countries. The ‘Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Action (NAMA)’ concept was first introduced in the ‘Bali Action Plan’ in COP13 in 2008 and, for developing countries, involves submission of GHG mitigation targets at the request of COP. In other words, the targets are only GHG mitigation ‘pledges’ (Decision 1/CP.13 ‘Bali Action Plan’, Decision 1/CP.16 ‘Cancun Agreements’, Decision 2/CP.17 in Durban and Draft, Decision -/CP.18 ‘Doha Climate Gateway’). Moreover, developing countries are welcome to propose their actions and targets for GHG mitigation under the voluntary basis of the UNFCCC. As of October 2012, 54 countries had proposed mitigation pledges that included NAMA implementation. Thailand communicated its NAMA pledge to UNFCCC in COP20 in Lima (Dec. 2014).

In the convention-track decision, developing countries agree to take on NAMAs, supported by technology and finance, based on their goal as being ‘aimed at achieving a deviation in emissions relative to ‘business-as-usual’ emissions in 2020’. Developed countries are urged to raise ambition levels of their targets ‘to a level consistent with’ the latest recommendations of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Developed countries have been requested to prepare ‘low-carbon development strategies or plans’, and so have developing countries.

The term ‘NAMAs’ refers to any national climate policy that leads to reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in developing countries. The mitigation pledges communicated to UNFCCC by signatory countries of NAMA agreements can be classified into four main groups: (1) NAMA concept, (2) NAMA plan, (3) NAMA implementation and (4) NAMA submitted to the UNFCCC’s NAMA registry. Thailand’s NAMAs are in line with national sustainable development plans and are aimed at achieving GHG emissions reduction relative to ‘business as usual’ emissions in 2020, resulting in GHG mitigation. NAMAs have impacts that can be measured, reported and verified (MRV) and comprise two types in Thailand: (1) domestically supported NAMAs and (2) internationally supported NAMAs. Both types require MRV processes to verify actual emission reductions and to provide transparency of the processes. In 2014, Thailand constructed a national strategy ‘Roadmap to Thailand NAMAs 2020’ with clear targets to set up benchmarks and orient emission reductions activities. In December 2014, the country announced its NAMA pledge with a GHG reduction target in the range of 7–20 % in COP20 in Lima. The pledge communicated to UNFCCC was approved by the cabinet, the national climate change committee and NAMA subcommittee and stakeholder consultations. As this pledge has no legal binding for the country, the final NAMA pledge process only needed approval at the cabinet level (see Fig. 6.1), and if it were legally binding, it would have required parliamentary approval, in accordance with the constitution. In such case, the Department of Treaties and Legal Affairs of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs would be involved. If the post-2020 mitigation pledge involves legal binding, the domestic processes leading up to communication to UNFCCC will require more time.

3 Implementation of a Climate Change Mechanism in Thailand

In 2012, the first study by Thailand Greenhouse Gas Management Organisation (TGO) showed that Thailand has a high potential for GHG emissions reduction, via both domestically and internationally supported NAMAs, to the tune of about 23–73 million tonnes CO2 per year by 2020 or approximately 7–20 % of the total GHG emissions for 2020. The calculated abatement costs of NAMAs vary in the range 0–1000 USD/t-CO2. However, these CO2 reduction actions are voluntarily for Thailand. In order to convey its intent as regards being a main supporter for climate change reduction and GHG mitigation in SE Asia, Thailand has to be ready for the coming strategies in the proposed NAMAs. The TGO working group and the Ministry of Energy found that the national sectoral approach actions are composed of:

-

1.

Alternative Energy Development Plan (AEDP) 2012–2021 (updated in May 2012)

-

2.

Energy efficiency measures in industrial and building sectors, according to the act on energy conservation passed by the Ministry of Energy

-

3.

Biofuel promotion in the transport sector under AEDP

-

4.

The mass transit system, termed ‘environmental sustainable transport system’, by the Office of Transport and Traffic Policy and Planning (OTP)

Thailand’s mitigation pledge to UNFCCC has been prepared on the basis of these measures since 2012. In addition, co-benefits of NAMAs are also assessed, and they reveal positive aspects of GHG mitigation under the NAMA framework. The MRV process of these NAMAs requires cooperation among the related ministries.

3.1 Success of Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) Projects in Thailand

As of January 2012, TGO reported that the number of CDM projects issuing CERs had increased to ten, with a total CO2 reduction of 1.05 Mt-CO2. However, as developing CDM projects up to the issuance of CERs takes much time, it is recommended that Thailand’s NAMA process be made more flexible and simplified to reduce the overall processing time and that other developing CDM projects be switched to register in the NAMA category. It is anticipated that Thailand will fast-track projects under NAMAs. As of December 2014, 222 Thai CDM projects had received the letter of approval (LoA), accounting for a cumulative GHG reduction of 12.72 Mt-CO2. Of these, however, only 151 projects had been registered by the CDM Executive Board (CDM-EB) (with a cumulative GHG reduction of 7.25 Mt-CO2), and only 43 projects had received issuance of certified emission reductions (CERs) (equal to 6.92 Mt-CO2).

4 Overview of Energy, Environment and Socio-Economic Factors

4.1 Thailand’s Energy Sector

Thailand is the second largest economy in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and is categorised as a middle-income developing country. Since recovering from the Asian financial crisis in 1997, its economy has shown significant growth, rising to 224 billion USD in 2012 and growing on average at 4.07 % annually. Medium-term economic projections point to Thailand maintaining this growth rate (about 4 % annually), and one report (‘Thailand Power Development Plan 2010’, published by Ministry of Energy, Thailand) quotes a figure of 4.27 % for 2012–2030.

The population of Thailand expanded 2.4 times during 1960–2012 and reached 66.8 million in 2012. Two decades ago the average annual population growth rate dropped to 0.74 % and then to 0.46 % in the most recent decade. The urban population was reported as 34.4 % in 2012. Accompanying the expected gradual economic growth, infrastructure development, increased access to modern energy and high-income generation will lead to increased urbanisation in future; thus, the urban population is forecasted to rise to 60 % by 2050.

4.2 Primary Energy Supply and Final Energy Consumption

Behind Indonesia, Thailand is the second largest energy consumer in ASEAN and consumed over 70.5 Mtoe in 2011, amounting to just over 20 % of regional demand. Of this, 70 % was due to transport and industrial sectors, with the transport sector being the largest energy consumer in 2011 (25,466 ktoe), closely followed by the industrial sector (24,966 ktoe). The residential sector is the third (16,551 ktoe). Over the last two decades, the highest average annual growth rate in energy demand was recorded in the industrial sector at 6.78 %, followed by transport and residential sectors at 5.16 % and 3.1 %, respectively.

In terms of fuel mix, as shown in Fig. 6.2, petroleum products dominate the total final energy consumption (TFEC) at 47 %, followed by electricity at 18 %. The dependency on fossil fuels is significant, as petroleum products, coal and its products and natural gas amounted to 63 % of TFEC in 2011.

As regards total primary energy supply for the world, it doubled from 1973 to 2011. Figure 6.3 gives a comparison of fuel mix in 1973 and 2011. According to the figures, fossil fuels have maintained their dominance since the 1970s. Except for the increase in nuclear share, from 0.9 % in 1973 to 5.1 % in 2011, none of the non-fossil fuel shares exhibit significant increases, though some of them have higher incremental factors, such as solar PV and wind power. In addition, the contribution of oil to total primary energy supply (TPES) dropped from 46 to 31.5 %, whilst natural gas and coal increased to 21.3 % and 28.8 % in 2011, from 16 % and 24.6 % in 1973, respectively.

In 2011, TPES in Thailand was recorded at 127.9 Mtoe, whilst still only 0.97 % of the world and 8 % of Asia excluding China attained this figure due to an average annual growth rate of 6.74 % since 1990. As with the global statistics, oil has the major share in the fuel mix of TPES at just above 36 %, followed by natural gas at 32 % and biomass at 16.2 % in 2011. The natural gas share has grown considerably due to its increased use in power generation. On the other hand, growth in energy from coal has been restricted due to its environmental concerns in Thailand and had a share of about 12.3 % of TPES in 2011. However, the percentage for fossil fuels in TPES stood at about 85 % in 2011.

4.3 Thailand’s GHG Emissions

In 2000 Thailand emitted about 229 Mt-CO2eq, most of which is due to the power sector. It is followed by transport and industry sectors, each accounting for 44.4 and 30.3 Mt-CO2, respectively. Figure 6.4 shows sectoral shares of CO2 emissions in 2000 and in particular shows that the energy sector is the biggest CO2 emitter, accounted for 69.57 % of the total. The share of CO2 emissions in the agricultural sector is about 22.64 %. The forestry sector and carbon sequestration result in CO2 absorption of 3.44 %.

Breakdown of CO2 emissions by sector in 2000 (Source: Thailand’s Second National Communication, ONEP 2011)

The trend in Thailand’s GHG emissions shows an increase—in 1992 total CO2 emissions stood at about 100,033 kt-CO2, which then increased to 194,853 in 2009, and accounted for an average increase rate of 2.33 % per annum. The biggest CO2-emitting sector is the power sector, which was responsible for 41,838 kt-CO2 in 1992, and 81,797 in 2009, and accounted for an average increase rate of 5.14 % per annum. This is followed by the industrial, transport and building sectors, which accounted for average annual increase rates of 1.66 %, 2.00 % and 2.98 %, respectively.

In 2011, CO2 emissions of 206.4 Mt-CO2 were recorded, a contribution of only 0.66 % to the global figure. However, CO2 increased by 202.4 % over the last two decades. Of the total, 41.8 % came from the power sector in 2011, and second was transport at 28.52 % (58.87 Mt-CO2). However, although the emission quantity is still comparatively small, emissions from residential and commercial sectors have the highest average annual growth rate of 5.35 %, followed by the industry and the power sectors of 4.47 % and 3.89 %, respectively. A fuel-wise comparison of carbon emissions shows that by far oil is the largest emitter and was responsible for about half of CO2 emissions for 2011. Due to its high use in power generation, natural gas has also incurred considerable emissions (about one third of the total) followed by coal (about one fifth).

In the energy sector, the energy conversion processes in electricity power plants are the chief contributor to CO2 emissions, which are followed by combustion processes in industry and transportation. During 2002–2010, the corresponding CO2 emissions increased by 30.03 %, 18.78 % and 12.47 % in the power, industry and transport sectors, respectively. Therefore, it is recommended that related policy measures in GHG mitigation in the energy sector be focused on energy conversion processes and fossil fuel combustion processes in industry and transportation sectors. Thus, for Thailand’s NAMA, the first study focused on power generation, industry and waste to energy activities.

4.4 Other Air Pollutant Emissions

NOx emissions in 2011 stood at 971 kt-CO2 and during the period 1994–2011 increased by about 83 %. The transport sector is the major NOx emitter in Thailand and in 2011 was responsible for 307 kt-CO2, an approx. 31.6 % share of the total. However, power, manufacturing and others (agricultural, construction and mining) also emitted considerable amounts.

With regard to SOx emissions, the figures dropped considerably during the period 1994–2011, from 1326 kt in 1994 to 552 kt in 2011. Since the power sector is responsible for the highest SOx emissions, desulphurisation retrofits in power plants have decreased SOx emissions drastically. However, in 2011 the power sector emitted the highest amount at about 55 %. More than 96 % of SOx emissions in 2011 were produced from the power and manufacturing sectors.

5 Relationship Between Thailand’s Energy Policy and Climate Change

The energy policy of the Ministry of Energy of Thailand has three main strategy aims: energy security, promotion of alternative energy and increased energy efficiency in the enduse sectors, as follows:

-

1.

The energy security strategy aims at development and promotion of endogenous energy resources to satisfy domestic consumption. It includes cooperation with nearby countries in the development of energy sources and utilisation of renewable energy resources such as small hydroelectricity generation, development of nuclear power and utilisation of clean coal technologies.

-

2.

The alternative energy strategy was announced by the Thai government as a national agenda in 2008. Promotion and utilisation of alternative energy supplies include biofuels, biomass, biodiesel and waste to energy. In addition, renewable electricity generation from solar, wind and hydro has been targeted in the 15-year Alternative Energy Development Plan (AEDP) of the Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency (DEDE), Ministry of Energy. The first 15-year AEDP plan made in 2011 is divided into three periods: 2008–2011, 2012–2016 and 2017–2022. This plan will result in cumulative energy savings of 19,799 ktoe by 2022 and will account for 20 % of total final consumption in 2022.

-

3.

The increased energy efficiency strategy of DEDE aims at targeting energy savings in the residential, industrial, commercial and transport sectors. It includes promoting awareness and understanding of energy conservation, providing financial incentives to the private sector in retrofits of energy equipment for energy savings, peak load cutting in the commercial sector and R&D on minimum energy performance standards, building energy codes and mass transit systems. Efficient use of energy results in less investment in the energy supply (DEDE, 2009).

5.1 Revised Alternative Energy Development Plan: AEDP 2012–2021

As mentioned above, the first AEDP is divided into three subperiods and aims to promote renewable electricity generation such as biomass power, biogas power, small hydropower, solar power, wind power and waste to power. In January 2012, DEDE increased the target of 2012 AEDP to 25 % by 2021. To achieve this target in the revised AEDP plan, Ministry of Energy has provided financial support and mechanisms to promote renewable electricity generation in the form of ‘adders’ on the top of buy-back rates. Adders of different renewable energy sources will be given by different rates. The concept of these incentives is to make the renewable energy investment yield sufficient profits within given lifetimes under specified economic criteria. The target of renewable electricity generation in its first AEDP plan was 5604 MW, in which biomass power will share about 3700 MW and will account for 66 % of the total capacity by 2022 (see Table 6.1).

In 2012, the National Energy Policy Committee (which includes the prime minister) announced the revised AEDP plan. Total renewable power generation was to be 13,927 MW in 2021 with expected annual energy generation of 63,035 GWh in 2021. The largest share of power capacity will be represented by 4800-MW from biomass electricity generation (see Table 6.1).

5.2 Thailand’s 20-Year Energy Efficiency Development Plan

In 2011, the Ministry of Energy announced the 20-Year Energy Efficiency Development Plan (EEDP). This plan aims at cutting off overall energy intensity and total final energy consumption by 25 % and 20 %, respectively, in 2030. The main sectors targeted are transport and industry (EPPO 2011). EEDP will provide both mandatory actions and voluntary support to promote energy efficiency. The mandatory actions will comply with the 1992 Energy Conservation Act (ENCON Act) and the revised 2007 ENCON Act and minimum energy performance standards including energy labelling. The main form of support to promote energy efficiency is financial, such as incentives for measures proven to enable energy savings, incentives to promote the use and production of energy devices that comply with minimum energy performance standards and incentives to promote high energy efficiency vehicles.

5.3 Thailand Power Development Plan (PDP) 2010–2030

The Thailand Power Development Plan is the government-approved development pathway of the power sector for the period 2010–2030. Two objectives have been accomplished by developing this plan. First, the future peak power demand and the total energy demand have been forecasted. Second, a roadmap for power generation expansion to meet forecasted demand has been developed. The PDP 2010 plan has been revised several times for a variety of reasons and changes in national energy circumstances. The first revision was made since the peak demand in 2010 was significantly higher than as forecasted and capacity addition of independent power producers (IPPs) was lower than planned due to delays in plant construction. Then, due to lowered public acceptance for nuclear power as a result of Japan’s Fukushima incident, a second revision was prepared. The third and latest revisions were prepared based on three key issues: (1) to adopt forecasted power demand results, (2) to include the guidelines given in the revised Alternative Energy Development Plan (AEDP 2012–2021) and (3) to place more emphasis on energy security.

In PDP2010 Revision 3, to forecast power demand, energy saving programmes and energy efficiency promotions have been considered at a success rate of only 20 %, in accordance with MoEN’s (Ministry of Energy) 20-Year Energy Efficiency Development Plan 2011–2030. According to the forecasts, the peak generation requirement in 2030 is 52,256 MW, and net energy generation requirement is 346,767 GWh. These figures have been set as the baseline for preparation of the PDP. In addition, the following features can be highlighted. One of the considerations taken into account was keeping the reserve margin at the level of 20 % higher than the peak demand due to risk in the natural gas supply sources in western Thailand. In addition, diversification of fuel has also been considered to reduce the natural gas dependency. Another consideration was to maintain the share of nuclear power below the 5 % margin. In the plan, a capacity of 2000 MW has been planned for nuclear in 2026. Increasing the share of renewable power generation by 5 % from the level proposed in its PDP Revision 2 has been taken into account. In the PDP 2010 plan, adding 14,580 MW of renewable power capacity has been planned for the system, 9481 MW coming from domestic sources and 5099 MW via purchases from neighbouring countries. Promotion of cogeneration and increasing the power purchased from it were another assumption made, with cogeneration accounting for 6476 MW of capacity addition. In addition, 25,451 MW from combined cycle power plants and 8623 MW thermal power capacity, including 4400 MW of coal, have been added for the period 2012–2030. Altogether, 55,130 MW of new capacity has been added for 2012–2030, whilst 16,839 MW of capacity has been retired. At the end of 2030, net operating capacity stands at 70,686 MW for 2030.

5.4 Environmental Sustainable Transport System

The ‘environmental sustainable transport system’ was proposed and developed by the Office of Transport and Traffic Policy and Planning (OTP). The actions, which mainly involve a modal shift, fuel economy improvement and sustainable mass transit system, started in 2012. However, due to the long lead time for construction, this sustainable system is not due to be fully operational until after 2020.

6 AIM/Enduse Modelling of Thailand’s Energy System

The methodology used to develop Thailand’s NAMAs is based on a bottom-up tool, the ‘AIM/Enduse’ model. The Asia-Pacific Integrated Model (AIM) was developed by the National Institute for Environmental Studies (NIES) of Japan as the first and only integrated assessment model specific to Asia and was used to evaluate policy options on sustainable development particularly in the Asia-Pacific region (Kainuma et al. 2003). AIM/Enduse is a bottom-up optimisation model comprising a detailed technology selection framework within a country’s energy-economy-environment system. It can analyse mitigation scenarios by using both the AIM/Enduse model and AIM/Enduse tools. In the model, ‘energy technology’ refers to a device that provides a useful energy service by consuming energy. Energy service refers to a measurable need within a sector that must be satisfied by supplying an output from a device. It also can be defined in either tangible or abstract terms; thus, ‘service demand’ refers to the quantified demand created by a service; i.e. service outputs from devices satisfy service demands. The AIM/Enduse leader in Thailand is Prof. Ram M Shrestha, who has developed and analysed climate policies for several Asian countries, as well as Thailand.

In this study, the structure of AIM/Enduse for Thailand’s reference energy system was created using socio-economic assumptions obtained from related agencies such as the Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board (NESDB), Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT 2010) and DEDE (see Fig. 6.5). Then, the selected CO2 countermeasures are analysed. The AIM family tools could handle the problems in both general equilibrium and partial equilibrium modelling. Thus, the AIM/Enduse tool is highly suitable for analyses of CO2 countermeasures in Thailand’s NAMAs. Results from the AIM/Enduse modelling for Thailand’s energy system show that final energy consumption by economic sectors in the BAU will increase from 71,491 ktoe in 2005 to 113,384 ktoe in 2020 (see Fig. 6.6).

The steps of modelling analyses of Thailand’s NAMAs are as follows: (1) reviews of national policy measures related to CO2 countermeasures, (2) data collection and verification, (3) data processing, analyses and modelling by the AIM/Enduse tool, (4) development of CO2 emissions as baseline in the business-as-usual (BAU) scenario, (5) analyses of CO2 countermeasures and (6) discussion and conclusion on CO2 countermeasures under NAMAs (Limmeechokchai et al. 2013).

7 Designing a National Policy Framework for Thailand’s NAMAs

7.1 Criteria/Selection of CO2 Countermeasures

In the analyses of CO2 countermeasures (CMs) for Thailand’s NAMAs, the abatement costs of selected countermeasures from the national policies and plans, including their economic feasibility, were estimated. The selected countermeasures with appropriate abatement costs were proposed as measures for Thailand’s NAMAs (see Fig. 6.7). The proposed countermeasures for Thailand’s NAMAs were also assessed for their economic feasibility.

7.2 Domestically vs. Internationally Supported NAMAs

The CO2 countermeasures (CMs) obtained from the AIM/Enduse analyses can be classified into two types:

-

1.

Domestic NAMAs performed voluntarily by the Thai government, sinceCO2 abatement costs are not excessive and the CO2 CMs could utilise domestic technologies and know-how

-

2.

Internationally supported NAMAs which have high abatement costs and need support, technology transfer, know-how and capacity building from developed countries

7.3 Economic Assessment of Domestic and Internationally Supported NAMAs

In addition to the incremental abatement costs of CO2 countermeasures, the internal rate of return (IRR) of each identified CO2 CM has been analysed. Table 6.2 presents the IRRs of CO2 CMs for renewable power generation. The CO2 CMs with high incremental abatement costs tend to have low IRRs, such as the IRRs of wind and solar power without incentives or ‘adders’ of only 1.5 % and −5.5 %, respectively. When the adders are taken into account, the IRRs of wind and solar power increase to 10.8 % and 9.0 %, respectively. Therefore, both wind and solar power should be considered as internationally supported NAMAs and since need international support to promote the nationwide use of such technologies as CO2 countermeasures.

On the other hand, renewables powered by biogas, small hydro and biomass have low incremental abatement costs of 0.02, 0.69 and 2.67 US$/t-CO2, respectively. In addition to incremental abatement costs, their IRRs without adders are 8.8 %, 5.4 % and 4.0 %, respectively. When 2011 adders are taken into account, their IRRs increase to 14.0 %, 11.7 % and 11.3 %, respectively (see Table 6.2). These IRRs are sufficient and result in financial viability for the renewable power producers in Thailand. Therefore, biogas, small hydro, and biomass power must be classified as domestic NAMAs in Thailand.

For the waste-to-energy sector, from the IRR point of view the MSW of local landfill technology is the best CO2 countermeasure. However, the identified four MSW technologies show negative IRRs. The IRRs without 2011 adders for MSW-Local landfill, MSW-INC, MSW-BD and MSW-Controlled landfill are −1.3 %, −4.5 %, −6.0 % and −8.0 %, respectively (see Table 6.3). The corresponding incremental abatement costs are 32.85, 140.63, 164.73 and 395.32 US$/t-CO2, respectively. When adders were taken into account, their IRRs increase to 11.0 %, 9.0 %, 9.0 % and 10.0 % for MSW-Local landfill, MSW-INC, MSW-BD and MSW-Controlled landfill, respectively. Therefore, all CO2 countermeasures in the waste-to-energy sector will be considered as internationally supported NAMAs since they need financial incentives, technology transfers and capacity building.

For energy efficiency (EE) countermeasures, the payback periods of EE lighting, EE cooling and EE motors in industry were calculated (see Table 6.4). It was found that payback periods of the proposed countermeasures for EE NAMAs in industry are satisfactory. Their short payback periods for business investment are only 3.0–3.5 years. These results are consistent with the stakeholder consultation.

8 Framework for Thailand’s NAMAs

8.1 NAMA Pledge to UNFCCC

Thailand is assessed as having a high potential for GHG mitigation from both domestically supported NAMAs and internationally supported NAMAs, up to 72.99 Mt-CO2. Of this, 23.33 Mt-CO2 will be from domestically supported NAMAs and 49.66 Mt-CO2 internationally supported, as shown in Table 6.5. Figure 6.8 shows the potential CO2 reduction from Thailand’s NAMAs in 2020.

With respect to the potential for GHG mitigation from these measures in 2020, Thailand will be able to provide a draft mitigation pledge as a NAMA concept. Such information includes the base year and the potential of GHG mitigation when compared with the GHG emissions in the target year, 2020.

Thailand’s mitigation pledge as a NAMA concept was finalised in 2013. However, more analysis needs to be conducted on the policies in different sectors as well as examples of mitigation pledges submitted by other countries, e.g. China, India, Indonesia, Brazil, Mexico and Chile before drafting Thailand’s NAMA policies for the UNFCCC. This step is conceptually important in the development of NAMAs for the implementation phase. It is also beneficial to the country in terms of international financial support for the internationally supported NAMAs.

In conclusion, the total appropriate GHG mitigation by NAMA measures in the energy sector under domestically and internationally supported NAMAs in 2020 will be about 73 Mt-CO2, accounting for 20 % from the total GHG emissions estimated in the 2020 BAU, where the measures should be explained according to NAMA that:

Thailand will lower CO2 emissions by 20 % when compared to the BAU 2020 level.

The potential to reduce the GHG emissions by domestically supported NAMAs is one important measure which could demonstrate the effort Thailand is making as a developing country involved in global GHG mitigation, but, naturally, different countries have different limitations and motivations in developing domestically supported NAMA actions.

A further development in domestically and internationally supported NAMAs is to group NAMAs together, i.e. create ‘Bundled NAMAs’. For example, the Power Development Plan (PDP), waste to energy plan, increased energy efficiency in industrial and building sectors plan, promotion of bioenergy in the transport sector plan and increased energy efficiency in the transport sector plan could be combined as a bundle of NAMAs under Thailand’s NAMAs, which would demonstrate the importance of GHG emission reductions and funding sources. Thailand has considered carrying out further studies on the environmental impacts in other dimensions, sustainable development and financial availability of the government funds to achieve the 2020 GHG mitigation target.

8.2 Seeking Financial Support

In Thailand, it is found that there are two sources of domestic funds for the GHG mitigation in energy sector. The first is the ‘Energy Conservation Promotion Fund’ (ENCON Fund), which was established by the energy conservation act to provide financial support for the implementation of energy security and the development of renewable energy. It is responsible for funding efficiency improvements, renewable and alternative energy development, R&D projects, human resources development, public education, campaigns and environmental projects. The ENCON Fund is currently focused more on projects that follow the Thailand 20-Year Energy Efficiency Development Plan 2011 –2030 (EEDP) and Thailand 10-Year Alternative Energy Development Plan 2012–2021 (AEDP) but not the climate change issue.

The second fund is the ‘Energy Service Company Fund’ (ESCO Fund), which is supported by the Ministry of Energy. Its objective is to encourage private investment in renewable energy and energy efficiency projects. The ESCO Fund is financed by the ENCON Fund to encourage six kinds of investment: (1) equity investment, (2) ESCO venture capital, (3) equipment leasing, (4) credit guarantee facility, (5) technical assistance and (6) assistance for renewable energy projects in selling carbon credits. Due to its benefits, ESCO would appear to be a very worthy mechanism for the domestically supported NAMA plan.

However, as investments for projects tend to be very high, more funds should be provided to help operators. Such projects warrant further study, though procedures for requesting assistance from the ENCON Fund are still very strict and complex due to the limited and discontinuous nature of the fund, which affects motivation and which in turn is why implementation of NAMAs does not go according to plan or may not achieve the targets. Therefore, implementation of NAMAs will have to rely on funding and capacity building from international sources, such as the Green Climate Fund (GCF). It also needs the cooperation of developed countries such as Germany, despite the presence of limitations, complexity and difficulty in accessing the funds. The funding for GHG mitigation actions in Thailand has very high potential of necessity in the near future since domestic funds are not sufficient and there exist barriers for domestic funding.

In addition to RE and EE NAMA actions, Thailand’s transport master plan, the ‘environmental sustainable transport system’, which is a capital intensive plan proposed by the Office of Transport and Traffic Policy Planning (OTP), will also require international support. However, due to the long lead times of the transport system, this system will contribute less in the NAMA 2020 period but will play a key role in GHG reduction potential post-2020.

9 Building Consensus Among NAMA Stakeholders in Thailand

During 2012–2013, several NAMA workshops were carried out among stakeholders of GHG emitters in the power, industry and waste to energy and transport sectors to identify the appropriate GHG mitigation measures and potential in Thailand. As regards Thailand’s NAMA stakeholder workshops, the steps in organising stakeholder workshops by ONEP (2014) and TGO (2014) during 2012–2013 are as follows:

-

1.

Organising the workshops and work with experts in related GHG mitigation sectors in order to prepare GHG mitigation potential and mitigation plans in the power, industrial, transport and waste to energy sectors, including preparation of related documents to cover the issues discussed in the workshops

-

2.

Collection of Q&A and discussed issues in the workshops from stakeholders of power, industries, transport, waste to energy, ministerial officers, NGO and private sectors

-

3.

Summary report submitted to the policymakers in the related ministries

Barriers to Thailand’s NAMAs have been identified in the stakeholder workshops, including barriers to support for CO2 countermeasures (CMs). The identified CO2 CMs under NAMAs show that Thailand and other developing countries have taken the responsibility to prepare voluntary mitigation in the low-carbon development plans toward helping, together with developed countries, to solve global climate issues. However, Thailand and other developing countries require capacity-building assistance in preparing CO2 CMs under NAMAs. Further, developed countries need to provide support for developing countries in terms of capacity building, technology transfers of CO2 CMs and financial support.

It was agreed on by the stakeholders that Thailand needs to analyse the policies of all involved agencies, the structure of the organisations involved, the existing energy policies related to GHG emission measures and the barriers to implementing GHG mitigation actions in renewable electricity generation and energy savings in industry, building and transport sectors.

The implementation of GHG mitigation actions within the renewable electricity generation sector and the energy savings in the industry and building sectors can be performed using two approaches—‘project-based NAMAs’ and ‘sectoral-based NAMAs’. Both approaches have to be analysed for the amount of GHG reductions which will involve related organisations during implementation and MRV process. Thailand intends to set up an organisation or group responsible for the follow-up of NAMA implementation and NAMA MRV that will assume the role of ‘Thailand NAMA coordinator’.

On the other hand, Thailand has yet to familiarise itself with the ‘sectoral-based NAMAs’ since most of the actions are nonmarket mechanisms where the structure and process of the GHG mitigation actions are set up by the government, e.g. adders and feed-in tariff scheme for electricity generation from renewable energy (solar, wind, hydro and biomass), which have different types of energy sources, NAMA methodology and NAMA MRV measures. The sectoral-based NAMAs can be adapted for use with other policies in the energy sector, e.g. measures to promote energy efficiency, whilst energy savings in the building and industrial sectors will have different NAMA methodologies and NAMA MRV processes.

10 Co-Benefits of Thailand’s NAMAs

10.1 Energy Security Aspect

Co-benefits of GHG mitigation actions in Thailand NAMAs in terms of energy security have been assessed. The co-benefit aspects under consideration are of the following indicators: (1) Diversity of Primary Energy Demand (DoPED), (2) Net Energy Import Dependency (NEID), (3) Net Oil Import Dependency (NOID), (4) Net Gas Import Dependency (NGID) and (5) Non-Carbon-based Fuel Portfolio (NCFP), along with four co-benefits, which are (1) oil import intensity (OII), (2) gas import intensity (GII), (3) energy intensity (EI) and (4) carbon intensity (CI).

Results from analyses of energy security show that CO2 countermeasure implementations under Thailand’s NAMAs are able to increase national energy security since Thailand’s NAMAs are related to the promotion of renewable electricity generation, which will also reduce the use of fossil fuels in electricity generation and increase the energy efficiency in the industrial and building sectors. In the case of a GHG reduction of 20 % in 2020, the indicators for DoPED and NEID will be increased by 2.66 % and 10.56 %, respectively, whilst the indicators for NOID and NGID will be decreased by 3.65 % and 3.62 %, respectively, when compared to BAU for 2020. From the increase in renewable energy, the CO2 emissions can be reduced, which will result in an increased NCEP indication of 18.99 %.

In addition, the indicators on OII and GII will be decreased by 8.14 % and 8.35 %, respectively. Furthermore, the indicators on energy intensity and carbon intensity in the case of a GHG reduction of 20 % in 2020 will be decreased by 17.9 % and 18.3 %, respectively, when compared to BAU.

Therefore, promoting the use of renewable energy can increase the energy security indices and GHG mitigation in Thailand. In general, Thailand still has many kinds of useful renewable energy resources which have high potential to be utilised because Thailand is an oil-importing country, so it is important that the government give more attention to promote the renewable energy resources to replace the imported fossil fuels (Limmeechokchai et al. 2014).

10.2 Environmental Aspect

Thailand NAMA implementation will directly result in decreased fossil fuel consumption. Consequently, a large amount of GHG emissions will be mitigated. In addition, other gases from combustion of fossil fuels will be mitigated as well. Transport NAMA actions will directly improve local and city air quality. It was also found that Thailand’s NAMA actions will result in not only decreased CO2 emissions, but also decreased CO, NOx and SO2 emissions.

10.3 Economic Aspect

The GHG countermeasures in Thailand’s NAMAs have been assessed in terms of macroeconomic effects by using the input-output table. Results show that investment from the economic sector in Thailand’s renewable energy power plants can be increased, which will cause an increase in the domestic production when compared to the 2020 BAU scenario. It also means an increase in investment for biomass and hydropower plant power generation, despite the fact that domestic production will be decreased due to solar and wind power projects. However, decreasing GDP in 2020 will come from investment of the private and public consumption sectors due to imported commodities resulting from the import of renewable technologies such as solar PV and wind turbines. Employment in the country will increase in 2020 as a result of increased activity in electricity production from domestic biomass.

Results of macroeconomic analyses based on increased energy efficiency of motors and lighting in the industrial sector show no economic stimulus, which will decrease the GDP by 1.25 billion Baht, increase the imported commodities by 1.19 billion Baht and increase the investment of the private and public consumption sector in implementing new motors by 0.83 billion Baht. However, the energy efficiency measures will help decrease the import of fossil fuels and gain more benefit when compared to the decreased GDP and also increase Thailand’s energy security.

The analysis covering increased energy efficiency of cooling systems via installation of insulators for building envelopes and of lighting systems via upgraded light bulbs in the building sector shows that there is no increase in economic stimulus, which will decrease the GDP by 18.59 billion Baht, decrease the value of exports by 6.84 billion Baht and decrease the value of imports by 0.49 billion Baht. Moreover, the increased energy efficiency will decrease the private and public consumption sectors by 6.67 billion Baht and domestic production by 18.59 billion Baht. This means Thailand can reduce the amount of imported fossil fuels, which will outweigh the reduced GDP. This also increases Thailand’s energy security.

10.4 Social Aspect

It is evident that the EE NAMA actions in the residential and commercial building sector will result in reduced energy cost for households and building owners. The social aspect of Thailand’s NAMA actions has been assessed as savings per household and saving per unit of electricity consumption of buildings. In the NAMA case of a 20 % CO2 reduction in 2020, it was found that the annual electricity bill saving per household will be around 60 USD. This social aspect of co-benefits shows the positive impact of Thailand NAMA actions, and finally it helps readily adopt EE NAMA actions.

11 Layout of Roadmap to Thailand NAMA 2020

To achieve a GHG reduction of 7–20 %, as Thailand communicated in its mitigation pledge to UNFCCC in Lima COP20, the Office of Natural Resources and Environmental Planning and Policy (ONEP) under MONRE proposed a roadmap to Thailand’s 2020 NAMAs (see Fig. 6.9). This roadmap includes both domestically and internationally supported NAMAs (ONEP 2014). If GHG countermeasures implemented under Thailand’s NAMA roadmap during 2014–2020 successfully clear the MRV processes, the higher GHG mitigation target of 20 % in 2020 will be achieved easily. However, the NAMAs still need support in terms of capacity building, financing, technology transfer and removal of EE barriers (Asayama and Limmeechokchai 2014).

12 MRV of Thailand’s NAMAs: The Road to Success

Thailand has prepared a NAMA roadmap in relation to the estimated GHG emission reductions. The MRV process under Thailand’s NAMA actions complies with the UNFCCC process; thus, it will not cause more barriers to the NAMA MRV or the procedure according to the mitigation actions for both project-based NAMAs and policy-based NAMAs. Before pushing ahead with the projects, meetings with stakeholders must be held. These meetings need to be arranged by the agencies responsible for the MRV process, and MRV guidelines for each project need setting. This can be done by the working group and coordinator from the department of energy and climate change and by the working groups on GHG mitigation in the energy sector from the Ministry of Energy, together with the working groups from the Ministry of Energy and MONRE.

It was found that strategies for reduced GHG emissions from the use of renewable energy for electricity generation, increased energy efficiency in buildings and energy savings in industries are high priorities under Thailand’s NAMA actions. However, for the NAMA actions to be achieved successfully, the organisations and the MRV process have to be developed at the same time as the NAMA action.

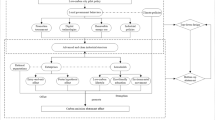

For the RE NAMA actions, the MRV process requires cooperation among ONEP, TGO, Ministry of Energy (Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency), Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC) and Energy Policy and Planning Office (EPPO) (see Fig. 6.10a, b). These agencies will be responsible for NAMA MRV so that NAMA actions will be achieved to meet the targets of the AEDP plan and the targets for GHG emission reductions following the NAMA actions.

For the EE NAMAs, the actions are related to energy efficiency in industry and buildings. The MRV process requires cooperation among TGO and the Ministry of Energy (Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency) (see Fig. 6.10c). These agencies will be responsible for NAMA MRV so that NAMA actions will accomplish the targets in energy conservation in industry and buildings and the targets for GHG emission reductions.

Finally, in October 2014, the ONEP revealed roadmap to Thailand’s NAMAs. It shows that the domestic MRV processes of both RE and EE NAMAs already achieve a CO2 reduction of 7 % (Fig. 6.11).

References

AEDP (2012) Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency (DEDE) (2012) The Renewable and Alternative Energy Development Plan for 25 Percent in 10 Years (AEDP 2012. published by Ministry of Energy, Bangkok, Thailand Available: http://www4.dede.go.th/dede/images/stories/pdf/dede_aedp_2012

Asayama Y, Limmeechokchai B (2014) Policies and measures to remove energy efficiency barriers in Thai Buildings toward NAMAs. In: International conference and utility exhibition 2014 on green energy for sustainable development (ICUE 2014), Pattaya, Thailand, 19–21 March 2014

Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency (DEDE) (2009) Building energy code. Ministry of Energy. Available: http://www.dede.go.th/dede/images/stories/energysaving12/15_2552.pdf

Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency (DEDE) (2010) Annual report: Thailand energy situation 2010. Ministry of Energy. Available: http://www.dede.go.th/dede/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1841&Itemid=318

Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency (DEDE) (2012) The renewable and alternative energy development plan for 25 Percent in 10 Years (AEDP 2012–2021). Ministry of Energy. Available: http://www.dede.go.th/dede/images/stories/dede_aedp_2012_2021.pdf

Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT) (2010) Thailand Power Development Plan (PDP2010: Revision3), published by EGAT, Bangkok, Thailand Available: http://www.egat.co.th/en/images/about-egat/PDP2010-Rev3-Eng.pdf

Energy Policy and Planning Office (EPPO) (2011) Thailand 20-year energy efficiency development plan (2011–2030). Ministry of Energy. Available: http://www.eppo.go.th/encon/ee-20yrs/EEDP_Eng.pdf

Kainuma M, Matsuoka Y, Morita T (2003) Climate policy assessment: Asia-Pacific integrated modelling, vol II. Springer, Tokyo

Limmeechokchai B, Winyuchakrit P (2014) Development of Thailand’s Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Actions (NAMAs) for low carbon society: energy security and co-benefit aspects. In: International Conference and Utility Exhibition 2014 on Green Energy for Sustainable Development (ICUE 2014), Pattaya, Thailand, 19–21 March 2014

Limmeechokchai B, Winyuchakrit P, Promjiraprawat K, Selvakkumaran S, Sritong N, Chunark P (2013) The development of mitigation pledge and Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Actions (NAMAs) in energy sectors: power generation, industry and designated buildings. Thammasat University Research and Consultancy Institute, Pathumthani

Office of Natural resources and Environment Planning and Policy (ONEP) (2014) Roadmap to Thailand NAMA 2020, published by ONEP, Bangkok, Thailand, December 2014

ONEP (2011) Thailand second national communication. Office of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy and Planning (ONEP), Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, Bangkok, Thailand. Available: https://unfccc.int/files/national_reports/nonannex_i_natcom/submitted_natcom/application/pdf/snc_thailand.pdf

Thailand Greenhouse gas organization Management (TGO) (2014) Status of carbon credits in Thailand, published by TGO, Bangkok, Thailand, December 2014

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License, which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Copyright information

© 2016 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Limmeechokchai, B. (2016). Designing a National Policy Framework for NAMAs. In: Nishioka, S. (eds) Enabling Asia to Stabilise the Climate. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-826-7_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-826-7_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-287-825-0

Online ISBN: 978-981-287-826-7

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)