Abstract

This chapter contextualizes the evolution of the private sector in the last decades and examines how this process has led to sustainability standards becoming an important tool for aligning commercial activity with the sustainability agenda. On the one hand, the global governance approach appears to be a potentially useful one for guiding private sector behaviour with the help of a set of globalized norms and regulations. On the other hand, corporate social responsibility is put forth as a useful instrument for activating sustainability standards in different processes and stages of private sector activity. These approaches are reviewed in the context of a particular country case—Mexico. Based on the existing literature as well as on interviews with representative bodies related to CSR and sustainability initiatives, it is suggested that in ensuring that the private sector engages with and contributes to the 2030 Agenda, frameworks such as CSR can prove useful in facilitating the implementation of standards and regulations to meet with larger social goals and expectations.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The last two decades of the last century were marked by several economic crises that started in the mid-1970s and resulted in a change from closed and protected economies to an open and export-oriented view. This new model was applied by several economies—developed and developing—and was understood in the terminology of ‘neoliberalism’ or the ‘Washington Consensus’ (Williamson, 1990). This change of paradigm sped up the globalization process in the 1980s and the 1990s, as it implied the liberalization of trade, finance, technological change, and the internationalization of firm activity (WTO, 1998). Among other things, it resulted in a rise in the number of free trade agreements, a consolidation of regional integration processes, and a renewed multilateral impetus signified by the rebirth of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) as the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995. This changing landscape had two significant implications for the concerns about the private sector.Footnote 1 In the 1980s, the main concern was around the adverse effects of firm activity, technological changes and a new environmental agenda. In the 1990s, concern was focused on the increasing competition among countries (developed and developing) and the role of governments in promoting good environmental policies for transnational corporations (TNCs) (Dunning, 2005; Fischer, 1999, p. 79).

In this period, as Dunning (2005) states, intergovernmental organizations such as the United Nations (UN) became more and more concerned about how the activities of governments, international organizations and TNCs could jointly contribute towards reaching social objectives and strengthening the benefits of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and globalization in recipient countries. Perhaps the most significant manifestation of such concern was the launch of the Global Compact by the UN in the year 2000 to support the development agenda as articulated in the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

Nowadays, the role of the private sector in the context of globalization, international cooperation and global governance is well recognized and the private sector is also a part of the current debates around sustainability (Rio + 20, green economy, green growth) and development [MDGs as well as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)], which bring these two strands of discussion together. In reflecting economic, environmental and social goals, standards play an important role in a broadened sustainable development agenda as they provide a common ground for different actors formally and informally linked to global governance.

The aim of this chapter is to review the role of the private sector at the beginning of the current century and to link it with the debate over social and environmental standards and regulations in the context of global governance. The chapter seeks to address the following guiding questions: what context best explains the current use of social and environmental standards and regulations by the private sector?; what conceptual approaches can help understand the current use of standards and regulations by this actor?; and what are the policy implications and trends around norms and standards for the international debates and the relevant actors?

The chapter is divided into two sections that cover the first two questions. In the first, the context is reviewed, and in the second, the framework of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) as an interface of the private sector with standards and norms is discussed. Finally, some concluding remarks relating to policy implications are presented.

2 The Relevance of the Private Sector

To understand the role of the private sector in the current use of social and environmental standards and regulations, we need to understand the context and evolution of this relationship. It is well recognized that firms bring positive outcomes for society, particularly through FDI and related effects on employment, technology transfer, balance of payments, market development and spillover effects. However, it is equally well-known that firms may bring negative impacts, also related to FDI, such as unemployment, delocalization of investment, low wages, pollution, and depletion of resources (Aziz, Lerche, & Lerche, 1995; Dunning, 1992; Stiglitz & Charlton, 2005).

Dunning (2005) identifies the evolution of TNCs and their influence at the global level, as well as some of the global initiatives to regulate them:

-

In the 1970s, the main concern was focused on the role of FDI in recipient countries and on the negative effects of TNCs. This opened the door to the first initiatives to regulate firm activity through guides, codes of conduct and multilateral agreements, such as the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, or the Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning the Multinational Enterprises of the International Labor Organization (ILO).

-

The 1980s were influenced by a deep technological change, trade openness and the new approach of ‘sustainable development’. This context facilitated a change of economic model towards a market-oriented approach, resulting in the strengthening of the private sector vis-à-vis state power.

-

By the 1990s, the international agenda started to get involved more closely with the private sector in order to make globalization and the effects of trade and investment a more balanced process, given the emergence of strong middle-income countries such as the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) and the competitive environment created as a result.

-

In the post-2000 phase, the context shows a clear and close involvement of the private sector with the international agenda, particularly oriented to a sustainable approach. Some of the most relevant initiatives in this period include the UN Global Compact that sought to incorporate the principles of human rights, labour standards, environment and anti-corruption in firm activity, and some other initiatives such as the ‘Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights’, developed by John Ruggie in his role as the UN Secretary-General’s Special Representative on Business and Human Rights and endorsed by the UN Human Rights Council in 2011.

As Schäfer, Beer, Zenker, and Fernandes (2006) and Elkington (1998) point out, since the 1990s, there has been a big movement, where the private sector has benefitted from the change in the economic model that has increased the volumes of trade and investment around the word. This expansion of firm activity has provided more profits to enterprises, more political power through lobbying, and more capacity to mobilize support for their processes worldwide. Such an expansion of the businesses implies a new division of labour at the international level and an expansion in the value chain of the firm. In this context, governments, civil society and different stakeholders demand more transparency, ethics and accountability from the private sector in its activities.

On similar lines, Dembinski (2003, p. 39) identifies three main issues where we can weigh the current relevance of the private sector at the international level: the aggregate weight of the non-financial enterprises in the world economy, comparing their weight with the poorest countries, and considering categories such as the ‘very big enterprises’ as forces of globalization. Based on this proposal, the relevance of such categories is examined in Fig. 1 and Table 1.

Source For FDI, UNCTAD statistics, http://unctadstat.unctad.org, and for ODA, OECD statistics, http://stats.oecd.org

ODA versus FDI flows, 1970–2013 (millions USD, current).

In order to demonstrate the current weight of the private sector compared with that of the public sector, a couple of examples may be cited; first, the comparison of FDI flows from the North to the South and the public flows of official development assistance (ODA) in recent years. As is clearly seen, private flows have overtaken the public flows, pointing at the new strength of the private sector (Fig. 1).

A second example compares the richest TNCs—or multinational enterprises (MNEs)—of the world by foreign assets (Table 1) against the gross domestic product (GDP) of some poor and low-income countries.Footnote 2 It is clear that the value of some non-financial TNCs—from developed and developing countries—is many times superior to the GDP of some countries, showing the economic power that firms have acquired as compared to countries (on the lines of Dembinski). For instance, the GDP of Samoa is roughly 964 times smaller than the foreign assets of General Electric and roughly 131 times smaller than those of Hutchison Whampoa Limited.

In addition, it should not be forgotten that firms cause increasing damage to the environment as part of their economic activity and patterns of consumption. The climate change consequences of firm activity have been widely documented since a couple of decades by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)Footnote 3 and by the Stern Review. Such a landscape requires a clear response from the public and private sector to strengthen social and environmental standards and regulations. One framework that facilitates the analysis of sustainable development, in the context of the relationship among different actors, such as the private sector, is the framework of ‘global governance’. Authors such as Rosenau (1995), Finkelstein (1995), Dingwerth and Pattberg (2006) are representatives of different approaches to this framework and most of them build upon the definition provided by the Commission on Global Governance that defined global governance as:

… the sum of the many ways in which individuals and institutions, public and private, manage their common affairs […] At the global level, governance has been viewed primarily as intergovernmental relationships, but it must now be understood as also involving non-governmental organizations (NGOs), citizens’ movements, multinational corporations, and the global capital market. (1995, pp. 1–2)

As per Dingwerth and Pattberg (2006, p. 189), global governance can be understood in two different ways. The first is as an analytical concept to explain the contemporary reality and the second as a normative view on how political institutions should react given the diminished strength of governments. Most importantly, ‘global governance is conceived to include systems of rule at all levels of human activity—from the family to the international organization—in which the pursuit of goals through the exercise of control has transnational repercussions’ (Rosenau, 1995, p. 13). It is useful to conduct the analysis of social and environmental standards and regulations for the private sector using the concept of global governance as a framework of reference. As Levi-Faur points out, ‘… scholars of global governance tend to focus on standards and soft norms’ (Levi-Faur, 2011, p. 3).

The negative effects of firm activity on the environment started to be recognized as a serious concern at the end of the 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s. Examples of the multifarious problems included depletion of the ozone layer, the rational use of natural resources (forests, oil, water, etc.), and ecological disasters (oil spills, chemicals, nuclear energy disasters). The international regimes on environment, sustainable development and climate change have become a relevant pathway to bring firms to be more accountable to the needs of the planet (dimensions related to the sustainable development approach). Some of the most relevant developments in this context include:

-

Creation of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) in 1972

-

Adoption of the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer in 1987

-

Brundtland Report that conceptualized ‘sustainable development’ in 1987

-

Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro that introduced the Agenda 21 in 1992

-

Kyoto Protocol in 1997

-

Johannesburg Summit in 2002

-

Rio + 20 in 2012

-

SDGs and the 2030 Agenda in 2015.

Concerns regarding the effects of firm activity would not be so significant if the influence of such activity were not so deep. What is needed is an approach that can help firms align their work with social and environmental standards and norms relating to the current agenda (Bruce Hall & Biersteker, 2002). The CSR framework can act as a bridge to facilitate this linkage.

3 The Corporate Social Responsibility Interface

In this section, the relevance of two relationships is examined—the linkages of social and environmental norms, standards and regulations with the private sector, and the linkages of the sustainable development approach with the CSR framework. These links seem to point to the same set of solutions to create new rules for different stakeholders to align their activities with the new sustainable development agenda based on the SDGs to be achieved by 2030.

First, when we refer to the private sector and link it with norms, regulations and standards, following ITC (2011, p. 1), we must consider the framework of public rules within which producers, exporters and buyers operate, as well as its growing interplay with private rules. Possible categories of research as identified by the ITC include:

-

private standards in global value chains

-

private standards’ impacts on producers and exporters

-

public and private standards interplay

-

public standards’ benefits for producers and exporters.

There is also a possibility of differentiating between public and private standards in the following ways (ITC, 2011, p. 1), even though there are overlaps:

-

Private standards tend to include requirements related to wider social and environmental aspects of production, e.g. working and living conditions at the farm/factory or even community level.

-

Public standards may focus on narrower aspects such as product and food safety as well as quality, but they also go beyond to address environmental (and worker) protection, for instance.

Büthe and Mattli further explain the differences between norms, standards and regulations, to appreciate their utility, in the following sense:

Like norms and regulations, standards are instruments of governance. But standards differ from most social norms in that they are more explicit. At the same time, standards differ from governmental regulations in that the use of, or compliance with, a standard is not mandatory. Only if a standard becomes the technical basis for a law or regulation – which often and increasingly occurs – does it become legally binding. (2010, p. 455)

On the same lines, the above-mentioned authors (Büthe & Mattli, 2011), quoted by the ITC (2011, pp. 5–6) propose the following typology of standards, whether public or private:

-

public non-market-based standards and norms developed by international organizations or domestic regulators (such as ILO labour standards)

-

public market-based standards established by competing public regulatory agencies of individual states or regional and multilateral standard-setting bodies (such as Codex Alimentarius)

-

non-market-based private standards set up by major private bodies (such as ISO 26,000, ISO 14,000, etc.)

-

market-based private standards developed by firms, NGOs, academia, industry associations, etc. (such as Fairtrade).

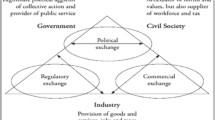

Once we can differentiate between public and private rules at the global or local level, a key question is ‘what to regulate?’, particularly by the private sector. Levi-Faur (2011) proposes that not only the private sector (market), but also the society (civil) or governmental actors (state), as regulators, can be categorized in eight ways in any governance system (Fig. 2). If we place the private sector at the core of the figure, we see through the diagram how firms create value for their different stakeholders, and by extension, the possibility of identifying what are the main aspects to be regulated. Figure 3, taken from the Stakeholder Theory (Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Parmar, & De Colle, 2010), illustrates this relationship between the firm and the value creation for others.

Source Levi-Faur (2011, p. 9)

What to regulate or standardize?

Source Freeman et al. (2010, p. 24)

Whom to regulate or apply standards to?

As part of the stakeholder theory, CSR becomes a helpful tool to develop social and environmental standards and regulations under the sustainable development approach. In addition, as Nuñez (2003, p. 5) points out, most of the CSR aspects are already included to some extent in the international standardsFootnote 4 relating to new concerns such as environmental protection. To contextualize briefly, CSR can be understood in its classical definition as ‘… the economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary expectations that society has of organizations at a given point in time’ (Carroll, 1979, p. 500; Carroll, 2008). While linking it with sustainable development, it has been proposed that the most accurate definition of CSR must incorporate not only dimensions of analysis like those identified by Carroll, but also incorporate the concerns of the different stakeholders of the firm (primary and secondary), at least in four main areas: government (states and public administration), society (consumers, NGOs and citizens), market (industries and competition) and nature (the environment) (Elkington, 1998; Nuñez, 2003; Raufflet, Lozano, Barrera, & García de la Torre, 2012).

The main theoretical frameworks that can be used to understand CSR include: the economic approach (Friedman [1962] 2002), the social performance theory (Carroll, 1979), the stakeholder theory (based on an ethical view) and the corporate citizenship approach (Melé, 2008, pp. 48–49; Mutz, 2008). Similarly, many initiatives related to norms and standards that incorporate different concerns around sustainable development can be identified. It is important to note that such initiatives under CSR go beyond many of the norms and standards with a social and environmental focus as they also include economic and financial dimensions.

Nuñez (2003) proposes a three-level classification of initiatives of CSR—global, regional and national—to guide the private sector under a sustainable development approach through norms, standards, principles, guides, codes of conduct, global indexes, and reports (Table 2). Table 2 can be complemented with later initiatives such as the ISO 26,000 on social responsibility for organizations, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) and its standard, or, at the local level in the Mexican case, the Sustainable IPC for the Mexican Stock Exchange and initiatives such as the ESR emblem provided by the Mexican Center for Philanthropy (CEMEFI) (Pérez, 2011) .

To illustrate the interface between the private sector, and social and environmental standards and regulations, through CSR, three key institutions in México are considered—The Mexican Center for Philanthropy (CEMEFI), The Global Compact Mexican Chapter (GCMC), and the Caux Round Table Mexican Chapter (CAUX)—as examples of the influence of CSR strengthening standards, norms and regulations locally. The main findings are listed in the Annex, and can be summarized as follows:

-

1.

There is a perception that CSR is influencing the strengthening of standards at value chain level, however, it seems this influence is limited to reputational rather than strategic considerations. Even then, some local institutions are promoting international initiatives around social and environmental norms and standards, such as the SR10 from IQNet adopted by the Mexican private sector.

-

2.

Related to the current state of social and environmental standards and regulations in México, new alternatives have been emerging lately. On the government side, institutions such as the Mexican Ministry of Labour (STPS), the National Institute for Women (INMUJERES), or the National Council to Prevent Discrimination (CONAPRED) have launched, in the last few years, initiatives such as the Norm NMX-R-025-SCFI-2015 against discrimination and labour inequality. From civil society and the international community, alternatives such as the certification of family-friendly enterprises (EFR) and the GCMC have emerged. A direct relationship can be perceived between each component of CSR and the local implementation of international standards and norms that cover all those areas, such as SA 8000 or ISO 9000 and some others. However, the coverage is still low, as Global Compact figures show (Annex).

-

3.

Finally, relating to broader initiatives or national platforms such as the ones promoted by the United Nations Forum on Sustainability Standards (UNFSS), there is a lack of knowledge of such work at the level of local stakeholders. However, local institutions such as the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT) have been working on the launch of labels and certifications on responsible consumption. The 2030 Agenda is likely to influence the implementation of social and environmental standards to attain the SDGs.

It is perceived, in general, that given the SDGs and the increasing involvement of the private sector in the sustainable development agenda, many other initiatives will appear at this interface, such as the Emerging Market Multinationals Network for Sustainability, the movement around impact investment linked, among others, with the International Finance Corporation (IFC) of the World Bank Group, the work of the UN around the promotion of the Global Compact, development agencies such as the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) and their work promoting business models for sustainable development, or the efforts around business and development carried out by the World Business Council for Social Development (WBCSD), the UNDP, the OECD or the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD).

As a concluding example in this context, we can consider a given ministry related to any environmental topic (water, forest, seas, lakes, etc.) in any developing country or emerging economy. Its technical department may manage a pool of contractors that can contribute, with their technology, to improve certain aspects regulated by this ministry (water filters, pipes, paper and packing materials, renewable energy technology, etc.). In collaboration with the international cooperation department, which also interacts with development agencies and engages in global debates, such pool of firms could increasingly be filtered based on general (or specific) norms and standards adopted by the international community in the labour and environmental areas. Applying the CSR approach, requirements that can be imposed include: that the firm belongs to the Global Compact; that the firm produces an Annual Sustainability Report that has been certified by the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI); or that the firm has achieved a local or international standard or certificate, such as the ISO 14,000 family, ISO 26,000, or in the Mexican case, the NOM-120-SSA1-1994 on health and sanitation practices in the processing of food, alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages etc.

4 Conclusions

The main aim of the chapter was to underline the relevance of the private sector in the context of social and environmental norms, standards and regulations in the world economy. In particular, the chapter sought to show that in the current situation, the evolution of the private sector must take place in a way in which, through the creation of certain norms and standards, the goals of the private sector can be aligned with the goals of society in order to guarantee sustainable development.

It was shown that the main activities of a firm along many of its processes (production, distribution and consumption) intersect with relevant aspects of the sustainability approach, i.e. to take care of the economy, of the society and of the environment. In this context, corporate social responsibility appears to be a framework that can help integrate the use of social and environmental standards into firm activity in the context of global governance, promoted both by public and private initiatives. This needs to be done not only for the sake of the local environment, but for the provision of global public goods. The 2030 Agenda can be an opportunity to promote the convergence of social and environmental standards and regulations with CSR, with the aim of better aligning the private sector’s and other actors’ activities with the SDGs. The Mexican experience shown here briefly can work as an example of how such convergence is in fact happening and contributing to the 2030 goals.

Notes

- 1.

As has been pointed out in many sources, the ‘private sector’ can be broadly understood, including not only large enterprises or firms of many sizes, but also chambers of commerce, firm associations, philantrophic foundations, worker-owned cooperatives, self-employed etc. (CCIC, 2001, p. 4; Pingeot, 2014, p. 17). In this chapter, by ‘private sector’ we mean mainly transnational companies since they are closely associated with global standards and regulations, However, it must be said that some small-medium-micro enterprises, and other private firms may also adopt, directly or indirectly, the same kind of norms and regulations.

- 2.

A list of the poorest countries was considered to illustrate the magnitude of difference in the value of some of the biggest non-financial TNCs against the income of some developing countries’ GDP. This can help illustrate the distance in economic value from firms to countries. This comparison may not be so relevant if we select developed countries or middle-income countries. Data is based on World Bank statistics.

- 3.

Some recommended readings on this include the Climate Change Reports from the IPCC, https://www.ipcc.ch/, and the Emissions Gap Report published by UNEP, http://web.unep.org/climatechange/cop21/publications.

- 4.

In this case, the reference is to standards related to human rights or labour issues, which have had a longer tradition within the UN and ILO. The Global Compact incorporates these two fields, plus two more contemporary concerns—environment and corruption. This is an example of international standards and principles for the private sector in the global governance context.

References

Aziz, A. S., Lerche, O. C., Jr., & Lerche, O. C., III. (1995). Concepts of international politics in global perspective. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bruce Hall, R., & Biersteker, T. J. (2002). The emergence of private authority in global governance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Büthe, T., & Mattli, W. (2010). Standards for global markets: Domestic and international institutions for setting international product standards. In H. Enderlein, S. Wälti, & M. Zürn (Eds.), Handbook on multi-level governance (pp. 455–476). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Büthe, T., & Mattli, W. (2011). The new global rulers: The privatization of regulation in the world economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Carroll, A. (1979). A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Academy of Management Review, 4(4), 497–505.

Carroll, A. (2008). A history of corporate social responsibility: Concepts and practices. In A. Crane, A. McWilliams, D. Matten, J. Moon, & D. Siegel (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of corporate social responsibility. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

CCIC. (2001). Bridges or walls?: Making our choices on private sector engagement. A Deliberation Guide For Action Against Poverty. Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Council for International Co-operation.

Commission on Global Governance. (1995). Our global neighbourhood (Report of the Commission on Global Governance). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dembinski, P. (2003). Economic power and social responsibility of very big enterprises: Facts and challenges. In UNCTAD 2004, disclosure of the impact of corporations on society: Current trends and issues.

Dingwerth, K., & Pattberg, P. (2006). Global governance as a perspective on world politics. Global Governance, 12(2), 185–203.

Dunning, J. H. (1992). Multinational enterprises and the global economy. Wokingham: Addison-Wesley.

Dunning, J. H. (2005). The United Nations and transnational corporations: A personal assessment. In L. Cuyvers & F. De Beule (Eds.), Transnational corporations and economic development, from internationalization to globalization (pp. 1–37). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Elkington, J. (1998). Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of the 21st century business. Stony Creek: The New Society Publishers.

Finkelstein, L. (1995). What is global governance? Global Governance, 1(3), 367–372.

Fischer, S. (1999). ABCDE: Past ten years, next ten years. In B. Pleskovic & J. E. Stiglitz (Eds.), Annual World Bank Conference on Development Economics 1998 (pp. 77–86). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J., Wicks, A. C., Parmar, B. L., & De Colle, S. (2010). Stakeholder theory, the state of the art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Friedman, M. ([1962] 2002). Capitalism and freedom (Fortieth Anniversary ed.). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

ITC. (2011). The interplay of public and private standards: Literature review series on the impacts of private standards—Part III. Geneva: International Trade Center.

Levi-Faur, D. (2011). Regulation and regulatory governance. In D. Levi-Faur (Ed.), Handbook on the politics of regulation (pp. 3–21). Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Melé, D. (2008). Corporate social responsibility theories. In A. Crane, A. McWilliams, D. Matten, J. Moon, & D. Siegel (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of corporate social responsibility (pp. 47–82). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mutz, G. (2008). CSR and CC: Social responsibility and corporate citizenship. In ICEP & CODESPA, Business and poverty, innovative strategies for global CSR (pp. 107–111). España: ICEP Austria, Fundación Codespa.

Nuñez, G. (2003). La responsabilidad social corporativa en un marco de desarrollo sotenible. CEPAL, GTZ, serie medio ambiente y desarrollo 72.

Pérez, J. A. (2011). La responsabilidad social mexicana, actores y temas. México: Instituto Mora, Universidad Anahuac, Red Puentes.

Pingeot, L. (2014). La influencia empresarial en el proceso post-2015. Madrid: Editorial Plataforma 2015 y más.

Raufflet, E., Lozano, J. F., Barrera, E., & García de la Torre, C. (2012). Responsabilidad Social Empresarial. México: Pearson.

Rosenau, J. N. (1995). Governance in the twenty-first century. Global Governance, 1, 13–43.

Schäfer, H., Beer, J., Zenker, J., & Fernandes, P. (2006). Who is who in corporate social responsibility rating? Gütersloh, Germany: Bertelsmann Foundation.

Stiglitz, J. & Charlton, A. (2005). Fair trade for all: How trade can promote development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Williamson, J. (1990). Latin American adjustment: How much has happened? Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics.

WTO. (1998). Annual report 1998. Geneva: World Trade Organization.

Acknowledgements

I appreciate the feedback for this work from Johannes Blankenbach from the German Development Institute/Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn and Archna Negi from the Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, and all the colleagues from the MGG network that attended the workshops of the project ‘Social and Environmental Standards and Regulations for the World Economy’. At the same time, I appreciate the time and inputs provided by Lorena Cortes from CEMEFI, Marco Pérez Ruíz from the United Nations Global Compact Network Mexico, and Walter Zehle from Caux Round Table Mexican Chapter for the interviews provided. The current text was developed between 2015 and 2016—at the beginning of the 2030 Agenda—and therefore focuses on the Mexican developments in the context of sustainability standards in that period.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Annex

Annex

Apart from literature, this chapter builds upon interviews on the relationship between CSR and social and environmental standards and regulations in Mexico with three experts from key local institutions:

-

Ms. Lorena Cortes (LC), Head of Research at the Mexican Centre for Philanthropy (CEMEFI)

-

Marco Pérez (MP), Coordinator of the Global Compact’s Mexican Chapter (GCMC)

-

Walter Zehle (WZ), Representative of the Mexican Chapter of the Caux Round Table (CAUX).

The interviews focused on three main aspects:

-

Question 1—What is the role of CSR in the strengthening of standards in Mexico?

-

Question 2—What is the current state of social and environmental standards and regulations in Mexico?

-

Question 3—Is there any progress on the configuration of a national platform on (private) sustainability standards like the one recently launched in India? (Note: The Mexican National Platform on Voluntary Sustainability Standards was subsequently launched in April 2018).

The following table summarizes the main findings of the interviews:

Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

LC | • CSR is currently influencing the strengthening of standards in Mexico, particularly at the value chain level • Defining a common concept of CSR and establishing its link with standards is still difficult • In many sectors such as agriculture or construction, there is a debate on the implications for corporations and their collaborators if CSR is implemented in those sectors. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) implement international standards as they are obliged to comply with the international benchmarks of multinational corporations in order to be accepted as part of their value chains • There is still the feeling that CSR standards can only be complied with by big corporations and not by local and small companies | • It is possible to identify a number of initiatives driven by different actors, but particularly the Mexican government through the Ministry of Labour (Secretaría del Trabajo y Prevision Social—STPS), has been recently promoting different labelling initiatives linked to the value chain of different sectors, e.g. for: – family-friendly enterprises (DEFR) (https://www.gob.mx/stps/articulos/distintivo-empresa-familiarmente-responsable-efr?idiom=es) – enterprises promoting inclusive labour (Gilberto Rincón Gallardo), and – farms free of child labour (DEALTI) https://www.gob.mx/stps/articulos/convocatoria-a-empresas-para-obtener-distintivos-en-materia-de-inclusion-laboral-y-contra-el-trabajo-infantil • Another example is the recent creation of the NMX-R-025-SCFI-2015 norm against discrimination and equal labour, developed by three governmental institutions: INMUJERES, CONAPRED and STPS (http://www.gob.mx/inmujeres/acciones-y-programas/norma-mexicana-nmx-r-025-scfi-2015-en-igualdad-laboral-y-no-discriminacion) • Finally, the private Fundación Más Familia awards the EFR certification to family-friendly enterprises based on CSR principles. It is a management model with presence in more than 20 countries and three core areas: family and labour conciliation, support for equal opportunities, inclusiveness. The levels of engagement are: firms, municipalities, education, social economy, franchises, micro-entities, global (http://www.masfamilia.org/iniciativa-efr/que-es) | The interviewee had no information regarding this question |

MP | The general opinion is that currently, CSR is still limited more to philanthropy and voluntary services rather than to sustainable business strategies. In practice, there is not yet an alignment between CSR and standards. CSR for many Mexican firms (mostly SMEs) still is a means and not an end | Although the number of norms has grown in the recent years, the challenge is still too big, because firms use them very little. Even though the Global Compact (GC) is one of the biggest movements worldwide related to CSR and some social and environmental standards, the number of firms engaged in the GC at country level (around 781 organizations and among them around 530 firms) is still low considering that there are almost five million firms in Mexico (The country has the third biggest GC network in the world, and the first in the Latin-American region. At global level, the GC accounts for 9000 firms and 3000 non-businesses https://www.unglobalcompact.org/what-is-gc/participants). There is a need to align initiatives such as GC, Global Reporting Initiative, etc. | The interviewee had no information regarding the specificities of social and environmental standards However, there was a perception that the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs offer new potentials for standards and indicators development as well as for their alignment with these global goals |

WZ | The CSR movement has influenced many local institutions and initiatives around standards and norms, for example: • Under ISO 26,000, IQNet (The International Certification Network) developed the SR10 certificate, an international standard on responsible and sustainable management that is supported and operated in Mexico by the Instituto Mexicano de Normalización y Certificación A.C. (IMNC) and by the Asociación de Normalización y Certificación A.C. (ANCE). (Private, independent multisectoral organizations that support the industry). Another case is the ‘Etica y Valores’ award presented by the Confederation of Industrial Chambers of Mexico (CONCAMIN) since around 15 years | There is a big influence of international standards on local standards and norms. In the case of CSR, for each CSR topic we can identify a particular standard, some of them international (e.g. SA 8000, ISO 9000 and many environmental standards) but at the same time referred to in Mexican laws and standards. For this reason, it does not seem clear why to consider the creation of (new) standards when most of the international standards are represented in local laws, norms or standards | There are no clear initiatives in this regard; however, the government will launch standards and norms relating to CSR (e.g. on responsible consumption) through institutions such as the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT). These are intended to complement regulations in promoting sustainability |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Pérez-Pineda, J. (2020). Corporate Social Responsibility: The Interface Between the Private Sector and Sustainability Standards. In: Negi, A., Pérez-Pineda, J., Blankenbach, J. (eds) Sustainability Standards and Global Governance. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-3473-7_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-3473-7_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-15-3472-0

Online ISBN: 978-981-15-3473-7

eBook Packages: Political Science and International StudiesPolitical Science and International Studies (R0)