Abstract

Ester Boserup promoted a focus on women’s role in agriculture as a new perspective through which to understand the link among economic, technological and agricultural development. Her work has been considered a starting point in understanding the importance of women’s role in development globally.

Her work remains important for analysing agricultural development and sustainability issues in Austria today. Time use is a crucial factor when making decisions on production strategies on Austrian farms. Currently, farmers aim to avoid having longer working hours and less income than employees from other sectors. Technological change can diminish the workload of farmers, but it does so mainly in regions that are favourable for large-scale industrialised agriculture. Sustainable agriculture with a focus on mixed production and the maintenance of cultural landscapes in a lively region must be attractive for young people, men and women alike, to keep them working on farms.

The on-going structural change in agriculture, with its implications for ecology and society, is one of the well analysed and documented long-term socioecological changes in Austria. Building models is one way to use this scientific knowledge as well as experts’ and farmers’ expertise for developing future scenarios and regional strategies for sustainable development.

This paper presents an agent-based model with single farm households as agents within the ecological and socio-economical setting of an Austrian region. The model assesses effects on land use patterns and socio-economic conditions induced by changes in the farms’ environment, such as changes in subsidies on the European and national level, changes in agricultural policy and changes in market prices of agricultural products. The decision-making process of each agent is simulated within a “sustainability triangle” of ecological, economic and social dimensions. Time-use data are used to integrate a gender perspective in the decision tree of farms, which was developed in a participatory process with agricultural experts and farm women of the region.

Three scenarios were developed and analysed, as follows: a trend scenario, a globalisation scenario and a sustainability scenario. The current problems of decreasing farm activities and increasing forests could be reduced at a certain level with the measures assessed in the sustainability scenario. However, as the model results show, in the sustainability scenario the unequal distribution of workload on women farmers would increase. This result must be considered when thinking about ways to enhance the success of any effort towards sustainable development.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Austria

- Agricultural labour time

- Agricultural change

- Long-term socio-ecological research

- Agent-based modelling

- Local case study

- Gender relations

1 Why Link to Boserup’s Approach?

Are women farmers a hindrance to progress in agriculture? Is progress in agriculture the solution for feeding the world? How can we find a path to develop agriculture without pushing natural, economic or social limits too far? Can we obtain greater insights into these issues if we study the role of women in agriculture and development?

Ester Boserup was the first scientist to ask these questions comprehensively. During her long career, she succeeded in developing a vast pool of data and insights. Ester Boserup promoted women’s role in agriculture as a new perspective through which to understand the link among economic, technological and agricultural development. Her work has been considered a starting point in understanding the importance of women’s role in development globally (e.g., Boserup 1970). Reading her work as students of social anthropology, sociology and biology, we were introduced to thinking about these questions in varying contexts.

Her focus on unequal workloads and strategies of using the available time enables researchers to grasp problems for which analysing solely economics will fail (Boserup 1965). It encouraged us to pursue time-use research as a non-reductionist approach for analysing social development, especially gender inequalities and dynamics, when tackling the problems of agricultural structural change.

Boserup was an economist working with economic and non-economic data and theories. She was apt to communicate and cooperate across disciplinary and academic boundaries. She was heard by scientists, public administrators and politicians alike. Our socioecological research is based on an interdisciplinary team working with stakeholders concerned with the problem in question. Here again, we believe that Ester Boserup gave a fine example of the importance of inter- and transdisciplinary research when attempting to find solutions.

In the current paper, we aim to show how we used the three-fold influence of Ester Boserup, i.e.,

-

A focus on women’s role in agriculture,

-

A focus on time use as important data beyond the economic and ecological factors and

-

An inter- and transdisciplinary approach,

as guidance in the research project “GenderGAP”.Footnote 1

In “GenderGAP”, we examined how changes in agricultural subsidies affect the economic, ecological and social situation of farms. We further investigated the factors—apart from economic factors—that influence decisions concerning the type and scale of production in small-scale family-run farms.

These research questions made it obvious that Ester Boserup’s work remains important for analysing agricultural development and sustainability issues in Austria today. Time use is a crucial factor in decisions concerning production strategies on Austrian farms. Today, farmers aim to avoid having a high workload combined with low income. Technological change can diminish the workload of farmers. However, in the setting of industrialised agriculture, efficiency gains can only be expected in regions that are favourable for large-scale industrialised agriculture. More sustainable forms of agricultural production, therefore, must focus on mixed production and the maintenance of cultural landscapes in a lively region and must be attractive for young people, men and women alike, to keep them working on farms.

Following this introduction, which draws a link between Boserup’s approach and the research undertaken, part 2 describes briefly the project in which this research was embedded. In part 3, we continue with a brief conceptual introduction to sustainable development and quality of life from a gender perspective. In part 4, we present the methods of agent-based modelling and its participatory application as well as the results for three scenarios. The final part recapitulates the significant findings and attempts to derive recommendations from them.

2 The “GenderGAP” Project—An Austrian Case Study

The on-going structural change in Austrian agriculture, with its implications for ecology (e.g., land use, material and substance flows) and society (e.g., regional development, food and crops, cultural landscapes), is one of the well analysed and documented long-term socioecological changes in Austria (Krausmann 2008; Rammer 1999).

In “GenderGAP”, we asked how the industrialisation and restructuring process that has been occurring in rural regions since the Second World War, and especially under the conditions of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) reform in 2003, can be analysed from a socioecological perspective (Fischer-Kowalski and Erb 2006; Fischer-Kowalski and Haberl 2007). What can we learn about the possible pathways to sustainable development if we study the interaction between social and ecological aspects of agricultural production? How can we create knowledge that can support social systems on their way to more sustainable solutions? We use the term “sustainable agriculture”, meaning a spectrum from an ecologically friendly type of agriculture, which is characterised by farms using less fertiliser and other artificial inputs than allowed by the EU subsidy scheme, to certified organic production without any non-organic inputs. Within this spectrum, we do not further differentiate the degree to which production is ecologically friendly. We choose building a model as a way to use scientific knowledge and the knowledge of agricultural experts and farmers to develop future scenarios and regional strategies for sustainable agricultural development.

As Austrian agricultural development is highly influenced by the Common Agricultural Policy of EU, in 2005, we began the project “GenderGAP” with the following questions:

-

What are the ecological, economic and social implications of the EU’s CAP reform of 2003?

-

Are women and men on farms affected differently by the CAP reform?

-

How can scientists, farmers and stakeholders create and use an agent-based model to work on future scenarios and strategies for a sustainable development of Austria’s agriculture?

The CAP reform adopted in June 2003 by EU agriculture ministers led to a profound transformation of the support mechanisms for the common agricultural sector. In particular, Brussels decoupling of the subsidies (which were previously bound to area use or livestock numbers) from the production volume had the intention to support a long-term perspective for sustainable agriculture.

Austrian agriculture produces much of Austria’s food and feed despite its Alpine environment. As a main player in the task of shaping the cultural landscape, agriculture is one of the touristic and ecological assets in these mountain regions (70 % of national area). Approximately 45 % of the national area is used as agricultural area and is worked on by only 5 % of the total people employed. Off the fertile lowlands, agriculture is characterised by small-scale family farms that produce dairy products and meat. It is further characterised by a high degree of organic farming (16 % of the national area) and a high percentage of women farmers (32 % of farms are headed by women; 17 % by married couples) (BMLFUW 2005).

The study region around St. Pölten, the capital of Lower Austria, is largely defined by the catchment areas of the two rivers Traisen and Gölsen. It extends from the political districts of St. Pölten in the north to the municipality of Lilienfeld in the south. We selected this region because it represents practically all production forms that are relevant for Austria within a relatively small area (Statistik Austria 2003). Whereas the share of the land used for agriculture is between 30 and 70 % in the northern municipalities in the St. Pölten region, only between 5 and 30 % of the land is used for agricultural purposes in the southern district of Lilienfeld. This proportion is reversed when forested area is considered, as 50 to 70 % of the land area in the south of the region is wooded. Because the technical aspects of modelling did not allow to consider the entire regions with all of their agricultural holdings, the two municipalities of Nussdorf ob der Traisen (in the north) and Hainfeld (in the south) served as case studies for modelling the southern and northern parts of the region.

In “GenderGAP”, we attempted to widen the analysis of the impacts of socio-economic conditions upon farms in two Lower Austrian municipalities by including a gender perspective. In cooperation with farmers and agricultural experts, time use was selected as an indicator that enables the integration of a gender perspective within an agent-based model (Smetschka et al. 2008). This model allows for a simulation of the social, ecological and economic conditions on farms and the evaluation of the living and working conditions of women and men farmers.

3 Sustainability Research, Gender Issues and Quality of Life

3.1 The Sustainability Triangle

In “GenderGAP”, the sustainability triangle served as the overall conceptual starting point for our research questions and the modelling process. The triangle sets the three aspects of sustainable development—economic, ecological and social—in relation to one another and translates them into economic prosperity, natural resource use and human wellbeing or quality of life (Fischer-Kowalski and Haberl 1998). There is a dynamic inherent in this triangle (Fig. 14.1): increased wellbeing requires increased prosperity, which requires increased resource use. From a perspective of sustainable development, it is necessary to analyse the logic of the dynamic within the triangle and to determine the crucial points for intervention.

Sustainability triangle. (Modified from Fischer-Kowalski and Haberl 1998)

Decisions that are made about the types and scales of agricultural production at a particular farm are influenced by numerous factors. Subsidies, production costs and product prices form the economic conditions under which agricultural production occurs. Influence is also exerted, however, by the regional labour market situation and opportunities for manufacturing and marketing (niche) products. General physical environmental conditions determine the production type and the options for either intensifying or extensifying production.

In addition to these environmental (or external) factors that condition the system “farm”, intrinsic characteristics of the farm itself affect the key management decisions. These characteristics involve social issues such as the planned transfer of farm ownership, the openness to innovation that often accompanies this and the size of the farm workforce. Family structure and the expectations and needs of family members in regards to their life and working conditions are determining factors for changes in agricultural production.

The primary goals of family-run farms are not growth and profit maximisation, but the achievement of a balance between income and expenditure (Vogel and Wiesinger 2003). In this respect, family farms can be defined as “peasant economy” or “domestic economy” (Chayanov 1966; Sahlins 1969). Questions concerning how much income can be achieved with how much land, livestock and working time form the basis for decision-making on the farm. Expansion and agricultural intensification represent opportunities to increase income sufficiently to secure the farm’s continued existence. Moving to more lucrative production branches or niche production may be a further strategy for achieving this goal.

The sustainability triangle serves as a framework within which decisions made by actors—in this case, farms as the agents of a computer model—can be analysed from a sustainability perspective, focusing on interrelations, impacts and limits. An agent-based model can consider these economic, ecological and social factors and the limiting factors that can be found both internally and externally.

3.2 Time-Use Approach as a Means for Analysing Changes in Gender Relations

Time-use surveys on the development and organisation of work have a long tradition in industrialised countries. These studies originally focused on paid working hours and the “normal” biography of a fully employed man. Since the 1980s, the discussions on gender relations and the gendered division of labour have led to a demand for data on paid and unpaid work. Time-use surveys are a regular part of the United Nations Statistical Division (UNSD) surveys: “Time-use statistics offer a unique tool for exploring a wide range of policy concerns including social change; division of labour; allocation of time for household work; the estimation of the value of household production; transportation; leisure and recreation; pension plans; and health-care programme, among others” (UNSTATS 2013). A number of European nations conduct time-use surveys on a regular basis. These data are widely used to analyse changes in gender relations (Aliaga and Winqvist 2003; Bundesministerin für Frauen 2010; Döge 2006; Sellach et al. 2005; Statistisches Bundesamt 2004) and socio-economic conditions such as family and household structures, working hours, recreational behaviour and consumption patterns (Gershuny 2000; Hartard et al. 2006; Schor 2005; Stahmer and Schaffer 2004).

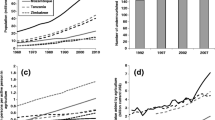

In “GenderGAP”, we used time-use data to model the agricultural development in an Austrian region. The agents in the model are farms modelled along the concept of the sustainability triangle according to their economic, ecological and social circumstances (Fig. 14.2). The quality of life of a farm family can be operationalised for a formal model as the family time budget. The family time budget consists of the number of family members multiplied by 24 hours per day. Time is a resource that is clearly limited and distributed equally to all. The opportunity for individuals to decide freely about how to use their time is, however, unequally distributed. In every case, individual time use differs with socio-economic and cultural patterns of division of labour according to age and gender. The social situation within the farm business comprises the family composition by age and gender and the possible and preferred working hours of all family members as a measure of quality of life (Gershuny and Halpin 1996).

Individuals use their time for the production and reproduction of four areas of life (Table 14.1) (adapted from Haug 2008; Fischer-Kowalski et al. 2011). This concept helps broaden the definition of working time, which in the current model includes the areas of family and household work, all types of para-agricultural tasks and the farm work per se. The model thus includes reproduction and subsistence activities, which are often the activities of women.

Studies on the situation of women in farming show that the traditional gender-related division of labour is changing slowly. This slow change relates to the fact that women farmers tend to have a higher workload due to their combination of various roles and responsibilities (Inhetveen and Schmitt 2004; Oedl-Wieser 2008).

We used data on farming and domestic working time from two comprehensive studies from 1979 and 2002 (Blumauer et al. 2002; Wernisch 1979) and agricultural statistics (Handler et al. 2006; Pöschl 2004) for Austria. This material was verified through several workshops and a series of qualitative interviews with men and women farmers and adapted for use in the model.

Time-use data have several functions in the model. They can help in the following ways:

-

Operationalise the changing needs of members of a family-run farm.

-

Depict ways to overcome divisions in the sphere of production and reproduction as supported by research on gender and women’s issues.

-

Facilitate differentiated treatment of subsistence work, para-agricultural activity, household and family work and agricultural production, particularly in the farming sector.

-

Support communication about quality of life and work and structural transformations in transdisciplinary research processes.

Because we focus on the gender perspective of living and working on a farm and on the changes that we can find and envision, time use seems adequate because of its inherent quality as a natural resource at the disposal of every individual equally, despite their sex, age or other differences. Another advantage of using time-use data lies in the limits that time represents. In the model, alternatives in agricultural production can increase income and working time. It is useful to be able to set the limits at the maximum of time available in a specific family. This farm family is a specific group of individuals—male and female children, adults and elderly—who must spend some time on their personal reproduction and some on care and group reproduction. Therefore, as a group, they only have a certain amount of time left for working on the farm.

3.3 Quality of Life: Time Use as a Bridging Concept Between Sustainability and Social Issues

In sustainability science, it is important to find indicators to assess quality of life and any changes therein. Time use is an integrative aspect of many facets of quality of life, and therefore can be used for monitoring changes in quality of life (Carlstein 1981; Fischer-Kowalski and Schaffartzik 2008; Garhammer 2001, 2007; Mischau and Oechsle 2005; Moe 1998; Mückenberger and Boulin 2005; Schaffer 2007). The terms “time scarcity” and “time affluence” (Heitkötter 2007; Kränzl-Nagel and Beham 2007; Rinderspacher 2002; Schor 2010) are used to link economic and social factors and to find alternatives to a solely economic notion of growth and development (De Graaf 2003; Kasser and Sheldon 2010; Sanne 2002). In its European Quality of Life Survey, Eurofound (the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions) examines a range of issues, such as employment, income, education, housing, family, health, work-life balance, life satisfaction and perceived quality of society. “Having sufficient time to fulfil both professional and personal goals—raising children, caring for older relatives, maintaining social and family contacts—is a crucial element in determining a good quality of life. However, findings from the European Quality of Life Survey 2007 indicate that work–life balance remains an elusive goal for many working Europeans” (Eurofound 2010, p. 3; see also Boulin 2003).

Linking sustainability research with time-use research is attaining some importance in socio-economic national accounting, non-monetary input-output approaches (Minx and Baiocchi 2010; Schaffer and Stahmer 2006; Stahmer et al. 2003) and other new attempts to strengthen socio-economic features within sustainability discourse (Chiou 2009; Hayden and Shandra 2009; Jalas 2002, 2008; Vinz 2005). An Australian survey on lifestyles, consumption and environmental impact includes time-use data as an important factor (Schandl et al. 2009).

Using time-use analysis helps to consider the quality-of-life aspect as one of the three aspects connected in the sustainability triangle. For the farms in the current model, we used the following data:

-

Farm and off-farm income and subsidies for the economic aspect of a farm,

-

Land-use and type of production for the ecological basis and

-

The time that the farming family used on work and other activities as an indicator of their social situation.

4 Agent-Based, Participatory Modelling and Scenario Results

4.1 Agent-Based Model of Two Villages

On the one hand, models can be used to reach a better understanding of dynamics within a system, reconstruct dynamics of past or ill-documented systems and develop future scenarios. On the other hand, they are useful for structuring communication processes on recommended actions. Many examples of modelling sustainable development are overly complex and elaborate to make without stakeholder involvement (e.g., IPCC 2007). With participatory modelling, we attempt taking a step towards translating knowledge about paths for sustainable development into societal action.

Agent-based modelling is a computer technique that allows the simulation of different actors as agents, the socio-economic and natural environment in which they are embedded and the interactions among agents and between agents and their environment. The simulation of these agents and their interactions according to the needs of a transdisciplinary working group makes these types of models particularly attractive. The similarities with a computer game add to this attraction (Fig. 14.4). Additionally, the equidistance of a computer game to the working practice of scientists and stakeholders involved helps foster the transdisciplinary process.

The current research questions require integrated analyses of ecological, social and economic factors and their interdependencies. A change in the economic framework conditions (e.g., CAP reform) simultaneously produces new preferences for women and men farmers regarding land use and the use of working time. These new preferences, in turn, have social and ecological consequences. We developed an agent-based model to analyse the interaction among these various factors and observe potential developments of socio-economic and biophysical processes in scenarios.

Each agent depicted in the model represents a particular farm that is characterised by more than 50 different features. In the case studies presented here, all agricultural holdings in the two municipalities of Nussdorf ob der Traisen and Hainfeld (Nussdorf 98, Hainfeld 105) are modelled. Referring to official statistical data (Statistik Austria 2003), distinctions are made among forestry holdings, forage growers, mixed farms, cash crop farms, permanent crop farms and graft nurseries. Demographic characteristics, e.g., the number of occupants in a household and household composition by age and gender, are also recorded. Other key attributes that flow into the model relate, for example, to family structure, farm succession, identifying whether the farm is run as the main or supplementary source of income and whether the farm is run with the aim of achieving future expansion. In accordance with the three dimensions of sustainability, the characteristics and attributes of the agricultural holding are assigned to the three spheres of social affairs, economy and ecology.

The environment in which the agents operate comprises natural environmental conditions together with the economic, social and political setting. The labour market, as a significant basic condition that affects farms, is represented in the model together with CAP subsidies and, in particular, payments related to the Austrian ÖPUL programme. The agents account for both aspects of their environment and other agents. This concerns not only subsidies but also production costs and prices for agricultural and forestry products. Agents calculate their household income using information on subsidies, production costs and prices for agricultural and forestry products. The available working time is calculated based on the household characteristics and perceived environmental conditions.

Farms annually make decisions regarding new patterns of land use and the utilisation of working time. Concrete decisions made on the farm are influenced by its internal structure, e.g., the number of agricultural workers on the farm and external framework conditions, e.g., subsidies for agricultural products. As agents, agricultural holdings have the opportunity, pursuant to differently weighted probabilities, to react to changes in their environment (e.g., a reduction in agricultural subsidies) and choose from a range of actions, including intensification, contraction, expansion, extensification, farm abandonment, converting production, moving to supplementary income activities, hiring external labour and direct marketing.

Interaction between agricultural holdings consists of leasing land from and to one another. Leasing and rental offers are collected at rental markets, and leasing agreements are made. Leasing agreements can only be made where lessor and lessee reside within 20 km of one another (according to the experts participating in the transdisciplinary research process). Where several such partners are available, the lessor and lessee are chosen at random from among them.

4.2 Participatory Modelling

Participatory modelling allows integrating the most relevant issues for stakeholders into the model and developing scenarios and strategies together with the stakeholders. The agent-based computer model was developed in a transdisciplinary research process (Fig. 14.3) in cooperation with six women farmers from farms representing the different production types and three experts from the Chamber of Agriculture.

During a total of four workshops at regular intervals over 2 years at the Lower Austria Chamber of Agriculture (Landeslandwirtschaftskammer NÖ, LLWK NÖ), a transdisciplinary working group took each of the steps from problem definition via model development to scenarios and options for taking action. As project partner, the department “Bildung, Bäuerinnen, Jugend” (education, women farmers, youth) within the LLWK NÖ played a central role in the project. The manager of this department facilitated contact with women farmers, most of whom were active as local farmers in the “Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Bäuerinnen” (working group of women farmers), and LLWK experts. Women farmers who were invited to the workshops were involved in distributing the project results. The inclusion of women farmers’ views and their expertise about farming decisions and family working time proved essential to ensure that the model depicted reality as effectively as possible.

At the same time, the method of participatory modelling fostered collaborative structuring of themes and mutual learning across inter- and transdisciplinary boundaries. Participating actors recorded that the process had been particularly interesting for them, not least because the discussions regarding the model had significantly increased their understanding of their own living environment and those of women farmers working in different farming and production environments.

4.3 Building Scenarios and Model Results

The main results of the research process are the three scenarios generated in collaboration with women farmers and representatives of the LLWK NÖ. They were developed in the course of the third workshop. Scenario building began with homogenous working groups, in which women from similar forms of agricultural production created stories of best-case scenarios for their farms and regions. We transferred these stories to a combined set of variables and calculated for the year 2020. The scenarios can shortly be defined as follows:

-

TREND-Scenario: Continuation of the current subsidy conditions and price relations

-

GLOB-Scenario: Substantial reduction of agricultural subsidies, liberalisation of the economy

-

SUST-Scenario: Increased support for environmentally friendly and sustainable production and consumption patterns.

The variables that were identified during the workshops as most relevant are presented as controls at the user interface of the model and may be individually adjusted. Among the controls for working and family situation are important factors for management decisions, such as farm succession, willingness to introduce innovations, the desired level of leisure time and minimum income. Alongside these controls, diagrams of the results are presented, in which the impacts of each respective change in the controls can be viewed after each run of the model (Fig. 14.4).

The model interface is a result of the participatory process. The aim was to find a consensus among all participants concerning which framework conditions are of general interest and exert a significant influence to merit appearing as interactive elements of the user interface. Discussion related to the directly observable results diagrams identified which areas were sufficiently relevant for users that their development should be simultaneously visible throughout the course of the model calculations.

Figure 14.4 shows the resulting model interface. It shows the municipality of Hainfeld, with the green circles representing farms working mainly with grassland, dark green circles indicating forests and brown circles representing crop land. The tables (yellow) show the percentage of farms that have terminated agricultural production and the number of farms moving from full- to part-time production. The orange slides can be used as controls of (1) prices and costs for conventional and organic farming, (2) different EU and national types of subsidies and (3) the social situation for farm production, showing (a) minimal income required, (b) importance of leisure time and (c) situation on the local labour market.

The main model results for agricultural development in the study area are as follows:

-

From 25 % to more than 40 % of all farms will go out of business.

-

Full-time farmers decline in all scenarios by at least 40 %.

-

Most of the surviving farms have forests in the GLOB-scenario.

-

In the SUST-scenario, land use diversity (grassland/forest/cropland) can be maintained.

-

Cultivated agricultural area diminishes by 50–80 %.

-

Animal stock is reduced by 50–90 %.

It is evident that the land area used for agricultural purposes decreases in all three scenarios, although it does so most strongly in the GLOB-Scenario and to the least extent in the SUST-Scenario. According to the GLOB-Scenario, this decrease leads to a concentration of a few intensively farmed large-scale holdings. In the SUST-Scenario, the reduction in the number of agricultural holdings is least among the three scenarios; the farms that remain enjoy relatively good living and working conditions. The share of grassland is highest in the SUST-Scenario and lowest in the GLOB-Scenario.

Modelling results show that the most sensitive parameters are

-

regional labour market and infrastructure,

-

production costs and prices/subsidies and

-

quality of life—minimum income and leisure time.

The results of this model show that strengthening the regional labour market does not lead to a reduction in the number of agricultural workers; instead, it contributes to the continuation of agricultural activity inasmuch as it becomes possible to stabilise the farm business through the creation of relatively attractive non-agricultural work opportunities. The measures associated with the SUST-Scenario would thus allow a sustainable development of agriculture to be fostered.

However, the SUST-Scenario also results in a larger share of work for women farmers than men farmers for grassland areas (Fig. 14.5). Time-use studies show that when household work, para-agricultural activities, agricultural activities and non-agricultural employment are added together, women farmers work more hours annually than men farmers. The scenario calculations show an increase in the workload inequality in the SUST-Scenario, rising from 100 to 200 h/y worked more by women farmers than men farmers. In contrast, this relationship is reversed in the GLOB-Scenario, with the workload of men farmers exceeding that of women farmers by 100 h/y.

The main outcomes of the agent-based model show that increasing forest area caused by a decline of agriculture in Austria could be reduced in a sustainability scenario. In this scenario, it is assumed that agricultural production becomes more attractive through fair prices and subsidy systems. Nevertheless, the workload of women farmers is much higher than that of men farmers in this SUST scenario, thus making working on the farm less attractive to women farmers. Thus, to enhance the success of any effort towards sustainable agricultural development, we must integrate time-use and gender aspects.

5 Sustainable Agriculture in Austria in Light of Ester Boserup

This project generated new insights with regard to the theme of gender and sustainable rural development through participatory modelling and integrating gender aspects into agent-based models. The gender perspective was incorporated into the model via time-use data. Time use illuminates important aspects of the quality of life of men and women, families, older people and children in farm settings. The focus on time use and the integration of working time for production, subsistence and reproduction shifts gender relations into the centre of attention and facilitates their placement as the subject of transdisciplinary working groups.

Participatory model design is well suited for articulating complex interrelations and causal chains and communicating these to the most diverse groups drawn from working practice, education and research. The inclusion of women as experts and the organisation of a women’s group strengthened the awareness among the women involved regarding their own expertise and opportunities for action as individuals and in the organisations to which they belonged. In the case of “GenderGAP”, it also contributed to the founding of the “Frauen in der Landwirtschaft” (Women in Agriculture) working group within the Lower Austria Chamber of Agriculture. Integrating women as experts also increased system knowledge and extended the approach to potential future scenarios and options for action. The future scenarios that were developed in focus groups and the scenario workshop were key elements and formed the basis for the creation of scenarios in the model.

Sustainable agriculture is interesting for small-scale farmers if it secures the survival of their family farms. In this interpretation, sustainability nearly equals the survival of small-scale farms. The farmers have little or no interest in growing the size of their farms, and they do not specialise or intensify production as long as they feel no financial pressure. This notion of sustainable agriculture can have dynamics similar to subsistence agriculture, as it means that many small farms have diverse non-specialised production and little technological input but depend on the family workforce.

Given a traditionally gendered division of labour on farms and better wages for men on the labour market, many forms of sustainable farming can lead to an even larger workload on women farmers. The feminisation of farming, as Boserup described it, in marginalised areas with labour-intensive but otherwise extensive forms of production can be observed in modern Austria.

In the transdisciplinary working group, the research finding of potentially increasingly unequal working hours kicked off the desire to develop options for action and strategies towards solutions that consider the needs of all members of a family-run farm, regardless of their age and gender.

To prevent the workload of women farmers from growing with the SUST-Scenario in regions comprised primarily of grassland cultivation with a high degree of traditional gendered division of labour and a high proportion of women workers in agriculture, it is necessary to offer attractive regional infrastructure with adequate care services for children and older people in the region. Good education and training opportunities for women farmers, effective public communication regarding the diverse roles taken by women farmers and support schemes for sustainable agriculture to the benefit of the wider society are further joint recommendations made by the transdisciplinary working group. Women farmers wish to play an active role in these areas. However, they must also participate in decision making so they can structure their life and work in the farm setting in such a way that family-run farms may continue to provide a satisfactory mode of life, high-quality food and maintain the cultivated landscape well into the future.

If organic and small-scale farming increases the workload of women in a traditionally gendered working environment, there are two options. Either farmers opt for less sustainable means of production or they stop agricultural activity altogether. Consequently, the ecological burden in favourable regions will increase (higher nitrogen flows in our model) and agricultural activity and, therefore, the maintenance of cultural landscape in less favourable regions will decrease (mostly reforestation). Farmers may also opt to adapt to socio-economic changes and find means of producing for the growing market of sustainable products with a new work organisation that is attractive for young people and does not place greater burden on farm women than men.

Pathways to sustainable development can only be identified in cooperation with women and men from both the field of research and working practice and through the inclusion of the gender perspective in sustainability research. If a high percentage of women farmers is a hindrance to “progress” in agriculture, this could be considered a driver of sustainable agricultural development that attempts to feed the world without pushing natural, economic or social limits too far.

Notes

- 1.

The project “GenderGAP. A gender perspective on the impacts of the reform of EU’s Common Agricultural Policy” 2005–2008 was funded by the Austrian research program TRAFO (Transdisciplinary Forms of Research); it was a partner project to “PartizipA. Participative Modelling, Analysis of Actors and Ecosystems in Agro-Intensive Regions”, funded by KLF (Cultural landscape research) and SÖF (German socioecological research).

References

Aliaga, C., & Winqvist, K. (2003). Wie Frauen und Männer die Zeit verbringen: Ergebnisse aus 13 europäischen Ländern. Statistik kurz gefasst: Bevölkerung und soziale Bedingungen, 12/2003, Thema 3. Luxembourg: Eurostat.

Blumauer, E., Handler, F., & Greimel, M. (2002). Arbeitszeitbedarf in der österreichischen Landwirtschaft. Irdning. Austria: Bundesanstalt für alpenländische Landwirtschaft Gumpenstein.

BMLFUW (Bundesministerium für Land- und Forstwirtschaft, Umwelt und Wasserwirtschaft). (2005). Grüner Bericht 2005. Vienna: BMLFUW.

Boserup, E. (1965). The conditions of agricultural growth: the economics of agrarian change under population pressure. Chicago: Aldine/Earthscan.

Boserup, E. (1970). Woman’s role in economic development. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Boulin, J. Y. (2003). As time goes by: A critical evaluation of the foundation’s work on time. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Bundesministerin für Frauen. (2010). Frauen und Männer in Österreich: Statistische Analysen zu geschlechtsspezifischen Unterschieden. Vienna: Bundeskanzleramt-Bundesministerium für Frauen, Medien und Öffentlichen Dienst.

Carlstein, T. (1981). Time resources, society and ecology: On the capacity for human interaction in space and time. London: Edward Arnold.

Chayanov, A. V. (1966). The theory of peasant economy: Edited by D. Thorner, R. E. F. Smith & B. Kerblay. Homewood: American Economic Association/Irwin.

Chiou, Y. S. (2009). A time use survey derived integrative human-physical household system energy performance model. Conference paper of the PLEA2009-26th Conference on Passive and Low Energy Architecture, Quebec City, Canada, 22–24 June 2009.

De Graaf, J. (2003). Take back your time: Fighting overwork and time poverty in America. San Francisco: Berret-Koehler.

Döge, P. (2006). Männer-Paschas und Nestflüchter? Zeitverwendung von Männern in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Opladen: Verlag Barbara Budrich.

Eurofound. (2010). How are you? Quality of life in Europe. Dublin: Eurofound.

Fischer-Kowalski, M., & Erb, K. (2006). Epistemologische und konzeptuelle Grundlagen der Sozialen Ökologie. Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Geographischen Gesellschaft, 148, 33–56.

Fischer-Kowalski, M., & Haberl, H. (1998). Sustainable development: Socio-economic metabolism and colonization of nature. International Social Science Journal, 158, 573–587.

Fischer-Kowalski, M., & Haberl, H. (2007). Socioecological transitions and global change: Trajectories of social metabolism and land use. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Fischer-Kowalski, M., & Schaffartzik, A. (2008). Arbeit, gesellschaftlicher Stoffwechsel und nachhaltige Entwicklung. In M. Füllsack (Ed.), Verwerfungen moderner Arbeit: Zum Formwandel des Produktiven (pp. 65–82). Bielefeld: Transcript.

Fischer-Kowalski, M., Singh, S. J., Ringhofer, L., Grünbühel, C., Lauk, C., & Remesch, A. (2011). Socio-metabolic transitions in subsistence communities. Human Ecology Review, 18(2), 147–158.

Garhammer, M. (2001). Arbeitszeit und Zeitwohlstand im internationalen Vergleich. WSI-Mitteilungen, 54, 231–241.

Garhammer, M. (2007). Time pressure and quality of life. In T. van der Lippe et al. (Eds.), Competing claims in work and family life (pp. 21–40). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Gershuny, J. (2000). Changing times: Work and leisure in post-industrial societies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gershuny, J., & Halpin, B. (1996). Time use, quality of life and process benefits. In A. Offer (Ed.), In pursuit of the quality of life (pp. 188–210). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Handler, F., Stadler, M., & Blumauer, E. (2006). Standardarbeitszeitbedarf in der österreichischen Landwirtschaft: Ergebnis der Berechnung der einzelbetrieblichen Standardarbeitszeiten. (Research report, no. 48). Wieselburg: Francisco Josephinum.

Hartard, S., Schaffer, A., & Stahmer, C. (2006). Die Halbtagsgesellschaft: Konkrete Utopie für eine zukunftsfähige Gesellschaft. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlag.

Haug, F. (2008). Die Vier-in-einem-Perspektive: Politik von Frauen für eine neue Linke. Hamburg: Argument.

Hayden, A., & Shandra, J. M. (2009). Hours of work and the ecological footprint of nations: An exploratory analysis. Local Environment: The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability, 14, 575–600.

Heitkötter, M. (2007). Aktuelle Ansätze lokaler Zeitpolitik. Zeitpolitisches Magazin, 10, 1–2.

Inhetveen, H., & Schmitt, M. (2004). Feminization trends in agriculture: Theoretical remarks and empirical findings from Germany. In H. Buller & K. Hoggart (Eds.), Women in the European countryside: Perspectives on rural policy and planning (pp. 83–102). Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing.

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). (2007). Climate Change 2007. Synthesis report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jalas, M. (2002). A time use perspective on the materials intensity of consumption. Ecological Economics, 41, 109–123.

Jalas, M. (2008). The everyday life context of increasing energy demands: Time use survey data in a decomposition analysis. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 9, 129–145.

Kasser, T., & Sheldon, K. M. (2010). Time affluence as a path toward personal happiness and ethical business practice: Empirical evidence from four studies. Journal of Business Ethics, 84, 243–255.

Kränzl-Nagel, R., & Beham, M. (2007). Zeitnot oder Zeitwohlstand in Österreichs Familien? Einfluss familialer Faktoren auf den Schulerfolg von Kindern. Vienna: Eurpean Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research.

Krausmann, F. (2008). Die Landwirtschaft Niederösterreichs in sozialökologischer Perspektive. In P. Melichar, E. Langthaler & S. Eminger (Eds.), Niederösterreich im 20. Jahrhundert. Band 2: Wirtschaft (pp. 261–269). Vienna: Böhlau.

Minx, J., & Baiocchi, G. (2010). Time use and sustainability: An input-output approach in mixed units. In S. Suh (Ed.), Handbook on input-output economics in industrial ecology (pp. 819–846). Berlin: Springer.

Mischau, A., & Oechsle, M. (Eds.). (2005). Arbeitszeit-Familienzeit-Lebenszeit: Verlieren wir an Balance? Wiesbaden: Vs Verlag.

Moe, K. S. (1998). Fertility, time use, and economic development. Review of Economic Dynamics, 1, 699–718.

Mückenberger, U., & Boulin, J. Y. (2005). Times in the city and quality of life. Dublin: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions.

Oedl-Wieser, T. (2008). The rural gender regime: The Austrian case. In I. Asztalos Morell & B. Bock (Eds.), Gender regimes, citizen participation and rural restructuring (pp. 283–297). Oxford: Elsevier.

Pöschl, H. (2004). Frauen in der Landwirtschaft: Ein nachrangiges Thema in den Agrarstatistiken. Wirtschaft und Statistik, 9, 1017–1027.

Rammer, C. (1999). Industrialisierung und Proletarisierung: Zum Strukturwandel in der österreichischen Landwirtschaft. In Österreichische Gesellschaft für kritische Geographie (ÖGKG) (Ed.), Landwirtschaft und Agrarpolitik in den 90er Jahren: Österreich zwischen Tradition und Moderne (pp. 99–117). Vienna: Pro Media.

Rinderspacher, J. (2002). Zeitwohlstand: Ein Konzept für einen anderen Wohlstand der Nation. Berlin: edition sigma.

Sahlins, M. (1969). Land use and the extendet family in Maola, Fiji. In A. P. Vayda (Ed.), Environment and cultural behaviour: Ecological studies in cultural anthropology (pp. 395–415). New York: Natural History Press.

Sanne, C. (2002). Willing consumers-or locked-in? Policies for a sustainable consumption. Ecological Economics, 42(1/2), 273–287.

Schaffer, A. (2007). Women’s and men’s contributions to satisfying consumers’ needs: A combined time use and input-output analysis. Economic Systems Research, 19(1), 23–36.

Schaffer, A., & Stahmer, C. (2006). Women’s GDP: A time-based input-output analysis. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Volkswirtschaft und Statistik, 142, 367–394.

Schandl, H., Graham, S., & Williams, L. (2009). A snapshot of the lifestyles and consumption patterns of a sample of Australian households. Canberra: CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems.

Schor, J. B. (2005). Sustainable consumption and worktime reduction. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 9, 37–50.

Schor, J. B. (2010). Plenitude: The new economics of true wealth. New York: Penguin Press.

Sellach, B., Enders-Dragässer, U., & Libuda-Köster, A. (2005). Besonderheiten der Zeitverwendung von Frauen und Männern. Frankfurt a. M.: Gesellschaft für Sozialwissenschaftliche Frauenforschung e.V.

Smetschka, B., Gaube, V., & Lutz, J. (2008). Gender als forschungsleitendes Prinzip in der transdisziplinären Nachhaltigkeitsforschung. In E. Reitinger (Ed.), Transdisziplinäre Praxis (pp. 23–34). Heidelberg: Carl-Auer Verlag.

Stahmer, C., & Schaffer, A. (2004). Time pattern in a social accounting framework. Contribution to the 28th IARIW General Conference. http://www.iariw.org/papers/2004/axel.pdf. Accessed 19 April 2013

Stahmer, C., Ewerhart, G., & Herrchen, I. (2003). Monetäre, physische und Zeit-Input-Output-Tabellen: Endbericht für Eurostat. Luxembourg: Eurostat.

Statistik Austria. (2003). Statistik der Landwirtschaft 2001. Vienna: Verlag Österreich.

Statistisches Bundesamt. (2004). Alltag in Deutschland: Analysen zur Zeitverwendung. Forum der Bundesstatistik, no. 43. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt.

UNSTATS (United Nations Statistics Division). (2013). Allocation of time and time use. Introduction. http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/sconcerns/tuse/. Accessed 23 April 2013.

Vinz, D. (2005). Zeiten der Nachhaltigkeit: Perspektiven für eine ökologische und geschlechtergerechte Zeitpolitik. Münster: Westfälisches Dampfboot.

Vogel, S., & Wiesinger, G. (2003). Zum Begriff des bäuerlichen Famienbetriebs im soziologischen Diskurs. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 28, 55–76.

Wernisch, A. (1979). Wieviel arbeitet die bäuerliche Familie? Der Förderungsdienst, 2, 44–51.

Acknowledgments

“GenderGAP” was funded by “Transdisziplinäres Forschen” and the partner project “PartizipA” by “Kulturlandschaftsforschung”, both research programs of the Austrian Federal Ministry of Science and Research. We thank our colleagues and partners, and particularly Marina Fischer-Kowalski, for their critical and valuable comments on this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License, which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Copyright information

© 2014 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Smetschka, B., Gaube, V., Lutz, J. (2014). Working Time of Farm Women and Small-Scale Sustainable Farming in Austria. In: Fischer-Kowalski, M., Reenberg, A., Schaffartzik, A., Mayer, A. (eds) Ester Boserup’s Legacy on Sustainability. Human-Environment Interactions, vol 4. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8678-2_14

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8678-2_14

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-017-8677-5

Online ISBN: 978-94-017-8678-2

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)