Abstract

This chapter explores management from the perspective of a fishing community located in the Pearl Lagoon basin of the Caribbean Coast of Nicaragua. The chapter seeks to address the following questions: How do fishing households in the Pearl Lagoon area respond to management plans designed by regional agencies and national authorities? How is poverty understood and experienced by fishing families and individuals? How is access to land – meaning securing land and aquatic rights – affecting the livelihoods of the people living in fishing communities of the area? Which coping strategies have people undertaken to reduce the vulnerability of their livelihoods?

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

Vulnerability is understood here as “the degree to which a system or unit, such as a human group or a place, is likely to experience harm due to exposure to perturbations or stresses.” Kasperson and collaborators highlight three dimensions of vulnerability: exposure (to perturbations and shocks); sensitivity (of people and places, and the capacity to anticipate and cope with the stress); and resilience (ability to recover and adapt) (Kasperson et al. 2010, p. 236).

- 2.

All interviews were conducted in Creole English.

- 3.

This was particularly evident on issues related to community land rights. Our research team was invited to attend various community meetings in which a strategy for dealing with land claims was intensely debated among community members.

- 4.

For instance, with the support of the research project, a community workshop was conducted at the end of September 2009. This workshop was designed with the purpose of increasing local capabilities of fishermen and fisherwomen on cooperative management (legislation, operation, etc.). This topic seemed relevant for local fishers in the face of a promised loan on fisheries development promoted by government officers from the Nicaraguan fishing authority.

- 5.

The World Bank. Website: http://data.worldbank.org/country/nicaragua. Accessed 30 September 2009.

- 6.

The Contra War was sponsored by the US against the Sandinista Revolution that ousted the Somoza dictatorship in 1979.

- 7.

Human Development Index for 2009 can be consulted online at: http://hdrstats.undp.org/en/countries/country_fact_sheets/cty_fs_NIC.html.

- 8.

Fish of commercial value include: snook (Centropomus spp.), catfish (Bagre marinus), snapper (Lutjanus spp.), stripped mojarra (Eugerres plumeri, Gerres cinereus), whitemouth croaker (Micropogonius furnieri), mackerel (Scomberomorus brasiliensis), crevalle jack (Caranx hippos), and coppermouth (Cynoscion spp.). In addition, five species of shrimps are found in the Lagoon: brown shrimp (Penaeus aztecus), white shrimp (Penaeus schmitti), pink shrimp (Penaeus duorarum), and Atlantic seabob (Xiphopenaeus kroyeri) (Christie 2000, p. 32).

- 9.

For instance, Pérez and van Eijs note that the B. marinus, C. hippos, the bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas), and sardines (Opisthonema oglinum) are predominant in the dry season (from November through April/May); while snooks, whitemouth croaker, black mojarra (Lobotes surinamensis), tarpon (Tarpon atlanticus), and mackerel can be found over the whole year. Though, they are also predominant during the rainy season (from May until October) (Pérez and van Eijs 2002, p. 21).

- 10.

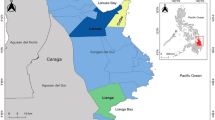

The communities of Awas, Raitipura, Kakabila, and Tasbapaunie are mostly inhabited by Miskitu people; while Brown Bank, Haulover, the town of Pearl Lagoon, Set Net and Marshall Point have historically been considered Creole-inhabited communities.

- 11.

However, during the second period of field research, a small group in Mestizo families was given temporary permission by Tasbapaunie for lodgings and to cultivate a plot of land in the western part of the Lagoon. The nature of this informal agreement was not entirely clear to us.

- 12.

For instance, unofficial estimates from 1992 reports 4,749 Afro-descendants and indigenous inhabitants (Christie et al. 2000, p. 22). In the 2005 census, this population is 6,394 (Williamson and Fonseca 2007, p. 59). This is about 26% of the population growth in a 12-year period. In addition, local population, particularly youth, have engaged more intensely in migration abroad as temporary workers on shipping cruisers in the US. These data might be unreported in official national or regional censuses.

- 13.

Two censuses were conducted: the first in February, and the second in July 2009. Our data registered 30% population growth in Marshall Point between 1992 (Christie et al. 2000, p. 22) and 2009. Multi-family households characterize Marshall Point’s social structure. Our survey revealed an average of 6.5 persons residing per household.

- 14.

- 15.

Kukras indigenous peoples inhabited the area of what is now called Kukra Hill, south of the Pearl Lagoon basin. Ethnographic studies suggest that Kukras are now extinct. However, families in Marshall Point still track their ancestors to the “kukras” from the Kukra Hill area.

- 16.

Nicolas Gutierrez Bennett, locally known as Uncle Pi, personal communication, Marshall Point, 26 February, 2009.

- 17.

This data is based on historical accounts provided by the community’s elders. Local narratives made references to Mr. Henry Patterson from Pearl Lagoon (referred to as “Mr. Patisson”), who served as Vice President of the General Council of the Moskito Reserve (see Von Oertzen et al. 1990, p. 322).

- 18.

“Wild Indians” was the term used by Uncle Pi to emphasize the indigenous/black ancestry of the founding families of Marshall Point (personal communication, Marshall Point, 26 February 2009).

- 19.

Men from Marshall Point took wives from Garifuna communities in the area. According to Davidson, Garifuna communities were founded between 1880 and 1912. Square Point was the first to be inhabited around 1880/1881, and Orinoco the last one, in 1912 (Davidson 1980).

- 20.

Three families were the first to set foot in Marshall Point: The Goff, the Bennett and the Peralta. They “divided” the community into three sections, uptown, middle town and downtown. It is interesting to note that these areas are said to be “private property” of the founder families who also hold original title deeds on their land.

- 21.

Several land grants were later annulated by the Nicaraguan government once it took over the Moskito Reserve in 1894.

- 22.

Nicolas Gutierrez (Uncle Pi), personal communication, Marshall Point, February 26, 2009.

- 23.

Ibidem. “Karob” in Creole refers to “Carib” which was a term commonly used to refer to the Garifuna people from the Caribbean Coast of Nicaragua. The term might have been used during the colonial period, when Spanish authorities used the term to label all the non-colonized (non Christianized) natives of the lowlands of Central America.

- 24.

Uncle Pi (personal communication, Marshall Point, February 2009). Kurinwas refers to the river that signals the west border of the Tasbapaunie’s land claim.

- 25.

“We joined with them (Tasbapaunie) because they recognize us as Indians. Yes, Indians for Indians” (Uncle Pi, personal communication, Marshall Point, February 2009).

- 26.

Local accounts also attest the common efforts in which both communities have been engaged with in order to protect their land and natural resources (Christie et al. 2000, p. 26) citing data from IPADE reports that between 1917 and 1957 Tasbapaunie was able to secure several title deeds over plots of land in their territory, as well as in the Pearl Cays.

- 27.

Adleen Bennett (personal communication, Marshall Point, February 2009).

- 28.

Dry-salted fish was also produced locally and sold in Bluefields or Managua (Joice Cayasso, personal communication, Marshall Point, February 2009).

- 29.

Ibid.

- 30.

Gill nets are used to catch fish in the rainy season. However, community members complain that gillnets have now also been used in the dry season. Shrimps are captured with cast nets mostly during the dry season. Trawling for catching shrimps is not allowed within the Lagoon (municipal ordinance). Lobster fishing is done by diving or by setting pots (or traps) out at sea – around the Cays, which are located between 1 and 10 miles away from the coastline.

- 31.

Leroy Bennett, personal communication, Marshall Point, 20 July, 2009.

- 32.

Uncle Pi, personal communication, Marshall Point, February 2009.

- 33.

State recognition of communal property rights on land has been a contentious issue in the history of the Coast. Lack of land surveying and titling sparked conflicts between coastal communities and the state since the Moskito Reserve was dismantled and placed under Nicaragua’s full sovereignty. Although some efforts were conducted to survey communal land early in the twentieth century, undefined property rights had been the norm until 2003 when a communal land bill was passed by the National Assembly.

- 34.

It is important to note that Marshall Point has identified its specific land claim within the overall territory that is claimed by Tasbapounie. Marshall Point’s authorities had initially decided to join the “Pearl Lagoon block” which is formed by 10 communities to pursue its land title deed. Afterwards, the community changed its position on the matter and reunited with Tasbapaunie. A common sentiment of collective struggle for land rights between both communities has made Marshall Point’s claim a relatively consensual process.

- 35.

In addition to contraction in demand, for instance, for lobster, the state of Florida has also banned the imports of snook. For the Coast, this resulted in falling prices for snook about 100% (Ibarra 2009).

- 36.

Since the approval of Law 445, communal authorities have “formalized” in written form their communal regulations. These regulations establish the norms and procedures through which local governing bodies are formed and operate. They also include some regulations regarding the use and exploitation of natural resources (Community of Marshall Point 2003).

- 37.

For instance, the local priest of the Evangelical church is also the head of the “society” directive board. The actual community coordinator – a woman – is a founding member of the Pentecostal church in town.

- 38.

Private banking did explore a few ventures for commercial agriculture, though with limited results.

- 39.

My translation.

- 40.

Since its inception, the project design adopted a participatory methodology which included, “a 6-month period of exploratory research resulting in the identification by local people of the need for a management plan for the basin’s natural resources” (Vernooy et al. 2000, p. 8).

- 41.

Government decree No. 043-98 issued by the Ministerio de Fomento, Industria y Comercio (MIFIC). The plan, according to DIPAL’s directors, “establishes the designated fishing zones, as well as the basic designs and manufacturing guidelines for the fishing gears permitted” in the Lagoon. See Pérez and van Eijs (2002, p. 3).

- 42.

Karen Joseph, regional delegate of INPESCA, personal communication, July 2009.

- 43.

For instance, in 1999, DIPAL placed an ice box (cooler) in the community for storing fish and shrimps. It also provided a boat and fuel. Lack of proper maintenance and management skills resulted in the shutting down of the local acopio. The person responsible for the ice box told us in an interview that “local community needs” were as important as storing fish. For instance, he provided fuel to families in need, and also advanced small cash amounts to fishermen. He saw no contradiction between community needs and the role that DIPAL was aiming to play in improving the well-being of the fishermen.

- 44.

Personal communication, Marshall Point, February 2009; emphasis added.

- 45.

For instance, the electoral law includes Marshall Point within circumscription 7, which comprises the “Garifuna” district. The law establishes that the first candidate heading the three-member list should be a “Garifuna.” Political parties and organizations have traditionally chosen residents from Orinoco, which is the largest Garifuna settlement in the Pearl Lagoon basin. This practice has meant that Marshall Point’s residents are continuously marginalized from the possibility of being elected into the Autonomous Regional Council. Since 1990, only two persons from Marshall Point have served as members of the Council.

- 46.

For instance, it is noticeable that the community’s regulations establish the notion of fishing “exclusive areas” that are said to be located “in the jurisdiction of the community.” See Community of Marshall Point (2003, p. 7, Chapter II, Article 30).

- 47.

Indeed, Tasbapaunie has “authorized” Marshall Point communal authorities to levy taxes over incoming fishing boats (fishers and buyers), from Pearl Lagoon and/or from Bluefields.

- 48.

Adleen Peralta, personal communication, Marshall Point, August 2009.

- 49.

“True fishers” for DIPAL, were distinguished from “occasional fishermen” who did not devote to full-time fishing. In 1997, DIPAL estimated that 100 fishermen were working on a full-time basis (Bouwsma et al. 1997). Our data from Marshall Point indicates that income from fishing is regularly supplemented with other household economic activities. Even in cases of well-known “traditional” fishermen, other sources of income are regularly pursued over the year. The most common economic activities in the community besides fishing are selling gasoline, petty trade (small stores), and occasional employment at housing construction. Waged-labor remains minimal and remittances from relatives abroad are becoming important. In the past, as suggested in various interviews, “people could live off their (hook) lines, fish and shrimps” (Herbert Bennett, personal communication, Marshall Point, February 2009).

- 50.

Ignacio Casildo, intervention in local community assembly, February 2009.

- 51.

As for August 2009, at least three cooperatives have already received the loan.

- 52.

The “project” was basically a form to be filled out by the “fishing cooperative” members (38 in total). Fishermen were asked to request a list of fishing gears and other related materials for the reactivation of the cooperative. The project requested 78,000 US dollars. See: Cooperativa de Pesca Artesanal. United Brothers and Sisters of Marshall Point (2009, p. 6).

- 53.

For instance, some community members voiced concerns with regard to the impact of this new fishing effort over the sustainability of the Lagoon. In addition, they argued that the loan might have a negative effect in the community, by increasing the existing socio-economic differences among fisher and non-fisher members of the community.

- 54.

This contradicts formal community regulation, which prohibits cattle from wandering within the community-inhabited areas.

- 55.

Herbert Bennett, personal communication, Marshall Point, February 2009.

- 56.

For instance, for the first time in history, since the inauguration of the regional councils, the FSLN has invited Marshall Point to propose pre-candidates for its first selection round to be held in Orinoco.

- 57.

Adlene Peralta, community coordinator, personal communication, Marshall Point, August 2009.

- 58.

Adlene Peralta, community coordinator, personal communication, Marshall Point, August 2009.

References

Allison E, Ellis F (2001) The livelihoods approach and management of small-scale fisheries. Mar Policy 25:377–388

Berkes F, Mahon R, McConney P, Pollnac R, Pomeroy R (2000) Managing small-scale fisheries. IDRC, Ottawa

Bouwsma H, Sanchez R, van der Hoeven JJ, Rosales D (1997) Plan de Manejo Integral de los Recursos Hidrobiologicos de la Cuenca de Laguna de Perlas y la Desembocadura de Río Grande. Proyecto para el Desarrollo Integral de la Pesca Artesanal en Laguna de Perlas (DIPAL) and Centro de Investigacion de los Recursos Hidrobiologicos (CIRH), DIPAL/CIRH, Laguna de Perlas

Caribbean Central American Research Council (1998) Diagnóstico General sobre la Tenencia de la Tierra en las Comunidades Indígenas de la Costa Atlántica. Informe Final. CCARC, Austin

Christie P (2000) The people and natural resources of Pearl Lagoon. In: Christie P et al (eds) Taking care of what we have. Participatory natural resource management on the Caribbean Coast of Nicaragua. CIDCA-IDRC, Ottawa, pp 17–46

Christie P, Simmons B, White N (2000) CAMPLab: the coastal area monitoring project and laboratory. In: Christie P et al (eds) Taking care of what we have. Participatory natural resource management on the Caribbean Coast of Nicaragua. CIDCA-IDRC, Ottawa, pp 99–126

Community of Marshall Point (2003) Internal regulation. Ford-BICU, Marshall Point

Cooperativa de Pesca Artesanal. United Brothers and Sisters of Marshall Point (2009) Proyecto: Adquisición de Materiales para Elaboración de Nasas y Fondos para Material de Trabajo. Marshall Point. Manuscript

Davidson WV (1980) The Garifuna of pearl lagoon: ethnohistory of an Afro-American enclave in Nicaragua. Ethnohistory 27(1):31–47

Envío (1989) Atlantic Coast pearl lagoon: back from wars and winds. Revista Envío, 92, March, Managua

Figueroa D (1999) “Historia del Pueblo Garífuna en Nicaragua”. In: Obando V (ed) Orinoco: Revitalización Cultural del Pueblo Garífuna de la Costa Caribe Nicaragüense. URACCAN, Managua

Friedmann J (1992) Empowerment: the politics of alternative development. Blackwell, Cambridge

Galeano L, Silva JA (2009) Hambre Cero Desvirtuado. El Nuevo Diario, 28 Sept 2009. http://www.elnuevodiario.com.ni/especiales/58070

Gonzalez M (2008) Governing multiethnic societies in Latin America: regional autonomy, democracy, and the state in Nicaragua, 1987–2007. PhD Dissertation. York University, Toronto, Canada

Hale Ch (1994) Resistance and contradiction. Mískitu Indians and the Nicaraguan State, 1894–1987. Stanford University Press, Stanford

Henriksen K (2008) Ethnic self-regulation and democratic instability on Nicaragua’s Atlantic Coast: the case of Ratisuna. Eur Rev Latin AmCaribbean Stud 85:23–39

Hostetler M (2005) Enhancing local livelihood options: capacity development and participatory project monitoring in Caribbean Nicaragua, PhD Dissertation Thesis. York University, Toronto

Ibarra E (2009) Procuraduría ayuda a Fiscalía de EU a perseguir empresas pesqueras en Nicaragua. El Nuevo Diario, 9 Jan 2009. http://impreso.elnuevodiario.com.ni/2009/01/09/nacionales/93052

Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censos, INEC (1995) Censos Nacionales. INEC, Managua

INPESCA (2007) Anuario Estadístico. Instituto Nacional de Pesca, Managua

Jentoft S (2005) Fisheries co-management as empowerment. Mar Policy 29:1–7

Kasperson JX, Kasperson RE, Turner BL II (2010) Vulnerability of coupled human-ecological systems to global environmental change. In: Eugene AR, Diekmann A, Dietz T, Jaeger C (eds) Human footprints on the global environment. Threats to sustainability. MIT Press, Cambridge, pp 231–294

Kindblad Ch (2001) Gift and exchange in the reciprocal regime of the Miskito on the Atlantic Coast of Nicaragua 20th century. Department of Sociology, Lund

Mukherjee Reed A (2008) Human development and social power: perspectives from South Asia. Routledge, London

Nietschmann B (1972) Hunting and fishing focus among Miskito Indians, eastern Nicaragua. Hum Ecol 1:41–67

Nietschmann B (1973) Between land and water: the subsistence ecology of the Miskito Indians, eastern Nicaragua. Seminar Press, New York

Pérez MM, van Eijs S (2002) Plan de Manejo para los Recursos Pesqueros de la Laguna de Perlas y la Desembocadura del Rio Grande de Matagalpa. DIPAL, Laguna de Perlas

PNUD (2005) Informe de Desarrollo Humano 2005. Las Regiones Autónomas de la Costa Caribe. ¿Nicaragua asume su Diversidad? PNUD, Managua

Sánchez BR (2001) Biología Pesquera del Camarón y Camaroncillo en las Lagunas Costeras de la RAAS. DIPAL, Laguna de Perlas

Vernooy R (2000) The setting, issues, and research methods. In: Christie P (ed) Taking care of what we have. Participatory natural resource management on the Caribbean Coast of Nicaragua. CIDCA-IDRC, Ottawa, pp 1–15

Von Oertzen E, Rossbach L, Wünderich V (eds) (1990) The Nicaraguan Mosquitia in Historical Documents 1844-1927. Dietrich Reimer Verlag, Berlin

Williamson D, Fonseca G (2007) Compendio Estadístico de las Regiones Autónomas de la Costa Caribe de Nicaragua. CIDCA, Managua

Acknowledgments

This chapter would not be possible without the invaluable assistance of Angie Martinez, my former sociology student at URACCAN, who generously introduced me to the people of Marshall Point. Along with Floyd Martin, they helped me conduct the interviews, provided valuable insights throughout the research process, and also offered comments to early versions of this chapter. Angela Fletes and Brenda Lopez provided support in data gathering through a household census. The community board as well as the fisherfolks’ cooperative of Marshall Point were supportive in all the phases of the research. Dennis Mairena (senior researcher, Centre for the Development of Indigenous Peoples, CADPI) offered advice on the socioeconomic and organizational dynamics of the Pearl Lagoon area. The initial research design benefitted greatly from conversations and intellectual exchanges with Svein Jentoft (Norwegian College of Fishery Science), and Camila Andreassen (PhD Candidate at the University of Tromsø). Georges Midre and Hector Andrade also provided substantial comments to early drafts of this chapter, and for that I am very grateful.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2011 Springer Science+Business Media B.V.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

González, M. (2011). To Make a Fishing Life: Community Empowerment in Small-Scale Fisheries in the Pearl Lagoon, Nicaragua. In: Jentoft, S., Eide, A. (eds) Poverty Mosaics: Realities and Prospects in Small-Scale Fisheries. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1582-0_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1582-0_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-007-1581-3

Online ISBN: 978-94-007-1582-0

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)