Abstract

Many species have declined or already gone extinct due to the human activities across the world causing what is termed the current sixth mass extinction event. The biggest determinant of species survival is the availability of a network of suitable habitat, affecting population size and eventual extinction risk. Considering that modern technology allows us to efficiently quantify habitat loss, species distribution data can inform us of the required minimum connectivity of habitats. Evolutionary distinctiveness (ED) is already part of conservation schemes to prioritize rare traits and unique phylogenetic history. However, so far none of these prioritisations quantifies the spatial constraints of a species to estimate long-term persistence based on the fragmentation of the landscape. Metapopulation capacity (λM) is one such measurement for quantifying fragmentation. Here we propose a combination of metapopulation capacity and phylogenetic distinctiveness to prioritize important specific habitat patches for evolutionary distinct species. We applied the new framework to prioritize island mammals and found Data Deficient and Least Concern species with a high combined value in ED and λM. Balancing between the extinction risks of solitary islands and the potential loss of unique evolutionary history of rare species on these islands can be a worthwhile exercise in prioritization schemes.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Conservation is an increasing necessity for the world (Pimm et al. 1995), and one that requires immediate action. Extinction occurs at a progressive rate, and we want to mitigate it before more species, known and unknown, are lost forever (Loehle and Eschenbach 2012). What is now recognised as the sixth mass extinction event is clearly attributable to anthropogenic action, mainly in the last few decades (Barnosky et al. 2011; Pereira et al. 2012). We will face great future challenges in preserving life on Earth, or at the least, in slowing down the rate of species loss. By setting priorities, as to which species or areas should receive the immediate attention, we can focus conservation efforts and resources in a bid to minimize the global biodiversity decline .

Evolutionary Distinctness

The EDGE of Existence program is a conservation program guided by a straightforward combination of two characteristics, evolutionary distinctness (ED) and global endangerment (GE); simply put, it prioritizes for phylogenetic rarity/uniqueness, and threat status (Isaac et al. 2007; Collen et al. 2011). ED is a species-level prioritisation that weighs each species by its relative importance with regards to the unique evolutionary history it represents as a consequence of its specific phylogenetic history. The calculation of ED is essentially distributing the amount of shared ancestry from the root to tip of a phylogenetic tree by hierarchically distributing each branch’s length equally to all of its subtending branches, thus accumulating evolutionary history up to the species level. This is calculated by taking the branch length and dividing by the number of species leading up to that branch, and then the ED of a species is the sum of these values for all branches from which the species is descended (Isaac et al. 2007).

For including global endangerment, the EDGE score adds the global IUCN assessment criteria by adding a quasi-probability of extinction associated with a doubling of extinction risk with increasing threat category (Isaac et al. 2012). However, the IUCN criteria include a wide, varied assortment of factors to determine the threat status of every species in the world. While some aspects of the criteria are standardized and quantified, others are somewhat equivocal terminology, ultimately based on expert opinion, particularly so when data is lacking (IUCN 2013).

Spatial Analysis

The importance of habitat to animals cannot be overstated, particularly when their long-term survival is at stake. It is important to take advantage of high-resolution habitat data and furthermore, to analyse and quantify the available space (Kerr and Ostrovsky 2003; Gillespie et al. 2008; Kearney and Porter 2009). By first focusing on the spatial aspects of a threat status, we may better assess what is often the main driver of species’ extinction. Then conservation areas can target protection of those species with rare traits that are simultaneously habitat-limited.

With access to environmental data that fundamentally shapes species distributions, we now have the possibility to reveal what we need to prioritize through modelling (Moilanen et al. 2009). Major conservation tools often focus on protecting either particular species or specific areas. Good examples of species prioritisation schemes include the IUCN Red List and the phylogenetically informed EDGE of Existence concept (Isaac et al. 2007; IUCN 2013). In combination with spatial approaches, prioritization allows us to recognise the urgency and mitigate using what limited resources are available to conservationists. So, how to refine this focus to some criterion that is both highly quantifiable and universally important?

Metapopulation Capacity

Gathering distribution estimates is difficult for rare or elusive species, and gathering population data more so, often because of the inaccessibility of their habitat which in turn biases ecological studies around the world (Martin et al. 2012). Population viability analysis can predict species trends, but such modelling also requires a certain level of life history data (Brook et al. 2000) that is unavailable for the full spectrum of species of concern. We have quality landscape data, but we want to know how this affects the species that reside in such landscapes.

Once such tactic is looking at metapopulation capacity (λM), calculated from spatial input (i.e. patch areas and distances) of spatially explicit metapopulation models. We can consider metapopulation theory as a compromise between landscape ecology and species distribution modelling (Hanski 1998). The resulting value is the capacity of a landscape to support long-term species persistence (Hanski and Ovaskainen 2000). λM is one way of assessing risk for species living in fragmented landscapes, as a relative quantification of fragmentation. Schnell and co-workers (2013a) further developed a modification of λM for large-scale landscapes.

Species’ habitats fragment over time, often due to human land use changes, and eventually the animals grow increasingly endangered. When isolated populations are too small and isolated, the metapopulation as a whole goes extinct. Therefore, λM can be useful in prioritising species conservation from a spatial standpoint (Hanski and Simberloff 1997; Hanski and Ovaskainen 2002; Schnell et al. 2013b). In the realm of conserving evolutionary history we can argue in much the same way, so combining the λM and ED could help us to prioritise and plan conservation areas in a spatially explicit manner, by factoring in the underlying processes of fragmentation, while balancing the objective of conserving evolutionary history.

We can even calculate λM at the patch level, allowing us to target specific areas within a species distribution for conservation prioritization (Ovaskainen and Hanski 2003). Since the spatial aspects would influence upon the evolutionary history of animals, we study this by quantifying isolation and size of patches (or islands). Relatedly, metapopulation theory itself was founded on such spatial assumptions of island biogeography (MacArthur and Wilson 1967).

Island Biogeography

Current global databases often lack the spatial and ecological granularity necessary to conduct such a large-scale analysis, without requiring great effort in obtaining and polishing the data. However, one way that we can at least test this proposed conservation prioritisation method is by examining islands, which we do here on mammals.

In this chapter, we use λM in combination with the current prioritization scheme of EDGE for two purposes. First, we investigate whether phylogenetic diversity correlates with characteristics of islands. We expect, based on the principles of island theory that predict lower immigration and emigration rates, that with increasing remoteness and decreasing size, species could accumulate evolutionary history. Second, we prioritise important islands containing an over proportional amount of evolutionary distinct species, indicating a potentially increased risk of living on small remote islands, requiring special attention. IUCN spatial data on species geographic ranges are typically somewhat general and broad, owing to the scope of species assessed. By incorporating more accurate, updated distribution data, we are vastly improving our collective understanding as to how threatened a particular species really is. We want to measure biodiversity value with readily available data and tools to identify conservation priority sites in a heavily fragmented landscape.

Methods and Materials

Islands are an ideal system to examine, because they are spatially segregated, but are also of importance, as they are home to many potentially important species under threat (Steadman 1995). We assume islands are associated with a greater ED than mainland areas, since islands are more isolated and therefore should be more likely to accumulate ED than other landforms. We already know that island area correlates with phylogenetic structure (Cardillo et al. 2008), and we too found a correlation between island size and ED.

The next logical question then is how could we quantify the different islands, with respect to species and each island’s overall community . We take the ED score of mammal species on islands, and then calculate the λM of every patch within a species’ distribution to prioritise spatially among the island patches. Metapopulation theory suggests that a population made up of smaller populations with potential gene flow might better persist than otherwise expected when considering each population alone and individually. Thus, distributions made up of closer, larger islands would be better off because of the increased probability of dispersal and rescue effect.

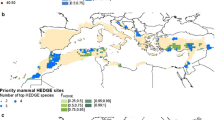

Global Self-Consistent Hierarchical High-Resolution Shoreline Data

We began with Global Self-consistent Hierarchical High-resolution Shorelines (GSHHS) data to identify island boundaries (Wessel and Smith 1996), before selecting out the qED (the position or quantile of the observed realised cumulative score) values from IUCN geographic ranges (see Safi et al. 2013). We considered islands closer to the mainland than 5 km as belonging to the mainland itself. Likewise, we clumped islands that had distances below 5 km on average to belong together and forming “connected” archipelagos. In order to assess the distances and identify archipelagos, we used the “raster” and “sp” packages in R (2.15.1). We first rasterised the GSHHS coast line with a resolution of 5 by 5 km. where a raster cell was considered landmass, if the grid cell lay on or touched a landmass. We then identified patches of connected raster cells using the queen’s case to decide on the connectedness of raster cells forming “clumps”. Following this procedure, we excluded all patches of connected landmass with an area equal to and larger than Greenland. Finally, we extracted from the original GSHHS vector data all those polygons that contained or touched the remaining grid cells, identifying islands, and archipelagos of the appropriate size and with the approximate required distances to each other and to the main lands. For all islands (and archipelagos), we overlay the IUCN geographic range data previously gridded to a resolution of 25 × 25 km onto the island polygons of the GSHHS vector data to identify the species and the respective ED scores for each island (see Fig. 1a).

(a) Map of GSHHS-defined islands, highlighting all those containing mammals for which we have ED scores. (b) The highest λM score (1.0) of IUCN -defined island mammals ranges, where endemics confined to one island are automatically assigned an λM score of 1.0. This indicates where the most valuable patches are within a species distribution, and consequently what would be most worth saving

Digital Distribution Maps of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species

We began with the datasets of terrestrial mammal species as defined by the IUCN Red List database (IUCN 2013). Then we focused on terrestrial mammal species living only on islands, and excluded all species that did not have distributions confined to islands only. We defined islands as landmasses smaller than Greenland (2,130,800 km2), with New Guinea (785,753 km2) as the largest island. IUCN’s terrestrial mammal spatial data had 1728 unique species identified as residing on an island. When we intersected this with the GSHHS shoreline data, which fulfilled our definition for island, there were 1501 species.

Finally, we restricted this to obligate islanders only, i.e. species not found on any continental mainland, and had 389 species with island-only distributions. We excluded those species with distributions that also encompassed continental mainland because we expected that they would not experience the same level of fragmentation threat as species with an island-confined existence. The mainland can be a potential population source that would not compare evenly in the calculations, particularly as our GSHHS data would not be able to define the species distribution extent on mainland.

Data Analysis

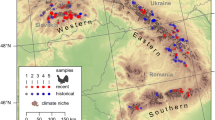

After finding those islands where both GSHHS and IUCN datasets intersected, we calculated the relative λM of every patch within a species’ distribution and scaled their values from 0 to 1.0, with the highest value indicating the island/patch that contributed most to the overall long-term persistence (see Fig. 2). We also designated any species with only one island/patch in their distribution automatically with a λM score of 1 (see Fig. 1b), because of its significant importance for that species. We then took these scores and for each, multiplied by the species’ ED score. To further give an average λM-ED score per island, we took the sum of species’ scores and divided this by the number of island mammal species (in our dataset) residing on that island.

Example map showing how the relative log-scaled λM scores rank within a species’ distribution. Here is the distribution of the Wallace’s three-striped dasyure (Myoictis wallacei), which occurs in the Aru Islands (Indonesia), and in the southern lowlands on the island of New Guinea (Indonesia and Papua New Guinea) from Merauke in the west to Avera on the Aroa River in the east (Leary et al. 2008)

Results

We found 40 Least Concern and Data Deficient species that possess a high combined score of λM and ED (see Table 1). In total, 42 of the island mammal species we assessed were listed by the IUCN as Data Deficient, 47 as Least Concern, with the remainder as threatened species. Those species already listed as threatened were potentially suffering from other threats (e.g. non-native species as predators/competitors). Focusing on those species that are Data Deficient or Least Concern and have higher λM-ED scores would be most beneficial, as their rarity indicate them to be at risk and a high λM value represents an important patch, and one that would pay off greatly to conserve.

The five islands with the highest average λM-ED scores, taken by adding all the scores and dividing by our (island-restricted mammals) species richness per island were Jamaica , Guadalcanal , Isle of Pines , Madagascar , and Nggela Sule (see Table 2, Fig. 3 for map). Interestingly, Madagascar held 39 of the highest λM-ED species, and ranked fourth in our λM-ED islands list.

Map highlighting the top five islands, coloured from warm to cool (i.e. red to blue), in decreasing λM-ED score (see also Table 2)

We found that combining evolutionary distinctness with λM revealed species that may be of concern that were not otherwise noticed. Because quantifying fragmentation effects on species takes into account spatial configuration, this can help to improve threat status assessments. The EDGE programme has already sought to visualize regions in the world with the most rare species and moved to prioritize those particular species. This adds a spatial understanding of the species distribution to that prioritization .

Discussion

Summary

We found Least Concern and Data Deficient island-restricted mammals that possess a high combined score of λM and ED. This method can be the start to finding species with a combination of phylogenetic rarity and long-term extinction risk due to island isolation. Further analyses are needed, as global prioritizations risk overgeneralizing among distinct animals, and yet suitable datasets, spatial and otherwise, are difficult to come by.

Island Studies

Islands represent less than 5 % of the earth’s land area , harbour 80 % of known species extinctions since 1500 (Ricketts et al. 2005), and make up 39 % of today’s IUCN Critically Endangered species (TIB 2012). Endangered island species, such as those targeted and listed in the Threatened Island Biodiversity (TIB) database, are currently of major concern due to invasive species. However, we can still examine the effects of isolation and area from an island point of view. On a global scale , this method aims to show which islands or species are most important for conservation, based on the spatial properties of the islands and the phylogenetic rarity of the species themselves.

Islands are a natural laboratory for evolutionary specialization and adaptation, because such an environment greatly shapes the select set of species living there in such isolation (Losos and Ricklefs 2009). From a conservation perspective, islands are unique because with less spatial area to begin with, they can only support smaller populations to evolve on them (Diamond 1975; Frankham 1998). Furthermore, recolonisation, the process responsible for maintaining population size from a larger source population, decreases because of spatial isolation and size (MacArthur and Wilson 1963, 1967; Simberloff and Wilson 1970), and dispersal amongst islands can be far more limited than on terrestrial “islands”. We expect that islands suffer more from stochastic extinction processes, in addition to anthropogenic effects such as introduced species, so they are on the whole in much greater need of immediate conservation action. In fact, islands have previously been the focus of research on prioritisation schemes for conservation planning (TIB 2012).

However, much complexity remains in studying islands. Most threatened species have small geographic distributions, and the distributions of island species are inevitably smaller than the distributions of continental species (Manne et al. 1999). Yet, some island populations can “show greater persistence than mainland populations of the same species, notwithstanding their smaller range sizes” (Channell and Lomolino 2000), perhaps reflecting the advantages of living in sheltered isolation. Another study found that island endemics are not relatively more threatened than continental ones, considering their distribution size, “suggesting that evolutionary isolation is not the reason for their vulnerability” (Purvis et al. 2000). Perhaps unravelling isolation and evolutionary factors can lead to a greater understanding of the unique state that island animals seem to occupy.

Small distribution area and island endemicity were the most important predictors of mammal extinction risk found through literature survey (Purvis et al. 2000). Because of such isolation, we would expect evolutionary history to reflect the spatial fragmentation. Moreover, there is a certain importance to the isolation of islands, given the limits of animal dispersal (Diamond 1974). For instance, the number of threatened endemic bird species has been found to correlate with deforestation on islands, and single-island endemics are considerably more at risk than more widespread species (Brooks et al. 1997), hence examining spatial aspects of islands is a sensible route.

Islands , particularly larger ones, are likely to contain multiple landscape types, and our islands borders, although defined at high resolution by GSHHS, can likely overestimate the amount of suitable habitat for a species. For instance, we found Madagascar ranked fourth in our list, but including additional information would scale down the habitat size from islands to the actual size of primary habitat. Then Madagascar might very well outrank all the other islands, due to unique species that possess ranges limited to parts of the island. With species records from GBIF and publicly available environmental layers, we could perhaps improve on this by creating approximate species distribution “maps” that we might be able to prune down the current IUCN extent of occurrence maps to a more realistically “fragmented” habitat extent. Calculating the λM of such maps would be an improved and more realistic estimate as to long-term species persistence.

It might be that island species have some adaptation for having historically small isolated populations, such that the little area available has shaped the species’ phylogeny (Cardillo et al. 2008). On the other hand, age of the islands (equivalently, patches) might have a significant influence on metapopulation persistence (Hastings 2010). It could also be that the most sensitive species were previously driven to extinction and modern day survivors have already been selected for (Manne et al. 1999). Human impact cannot be overestimated, because despite exceptional habitat loss on all terrestrial land types, “the human impact index” was considerably greater on islands (Kier et al. 2009). It is still a puzzle to be teased apart, how the interaction of intrinsic factors, e.g. innate biological susceptibility, and extrinsic factors, i.e. those mostly due to human impact, affect the outcome that ultimately leads to extinction (Bennett and Owens 1997).

Already there are numerous efforts underway to stave off the extinction of island species, such as the previously mentioned Threatened Island Biodiversity (TIB) database (http://tib.islandconservation.org/), whose primary focus is on eradicating threatening non-natives. The high levels of endemic richness already warrant special conservation protection (Kier et al. 2009). Species on continents can experience island effects, e.g. mountains or islands within lakes, which would still make island conservation studies, such as this, applicable to them.

Next Steps

Several aspects of this analysis can be modified depending on the user’s goals. For example, we took 5 km to be the minimum distance from continental mainland for an archipelago isolated enough to not experience a strong mainland source population. At one extreme, Davies et al. (2007) previously defined oceanic islands as those more than 200 km away from a continental shelf edge. Distance to mainland would understandably have different consequences on the species if (1) they have some portion of their metapopulation residing on the mainland, or (2) they are able to cross this water gap, albeit rarely. If this assessment was of larger sized islands or patches, one could implement a λM score per area (e.g. square kilometre).

It is worth mentioning that species richness does not play any role in this ranking. Species richness is an anthropogenic valuation scheme, and this method is unique in considering from the phylogenetic and spatial considerations of the animals themselves. However, something that could be accounted for is complementarity, as in the case where two islands contain the same sets of species. Many sophisticated spatial planning tools try to take this into account, one such being Zonation (Moilanen et al. 2005; Moilanen 2007).

It seems logical that species endemic to only one island require the most accurate distribution data, and most rigorous of assessments, because these cases have all their “eggs in one basket”. Incorporating movement functions would greatly improve the model’s connectivity aspect, determining how fragmented such oceanic islands are. The availability of such data is increasing, fortunately, and ideally they will improve habitat utilization and connectivity estimates in the future. This method can go beyond islands, however.

We had excluded those species with distributions including continents because of how it would influence the biogeography dynamics. Facultative islanders (of which we found 1611 species), those species with distribution on both island and continent, made up a longer list that could be worthwhile for further study. This would be an interesting question to tackle, because it would be a step closer to quantifying mainland “value” for islands, how to go about quantifying its contribution. Nevertheless, looking at only islands made for a simpler study, and a further interesting one is then to shift our focus towards continents. It would be more broadly useful, and also computationally challenging, to do the same analysis for higher precision information of animal distributions on the continents. The λM has the potential to identify important areas for connectivity, so that we might better respond to extinction threats, and therefore might be a better way of prioritising specific areas for conservation. This index weighs those island “patches” which are most valuable to species with limited ranges and for species with unique phylogenies. Future schemes could consider different weightings and combinations of these two indices. More importantly, for islands a score is calculated by taking an average score over all species.

As for island species, we would like to compare our lists with the outcome of the EDGE zones papers. It would be interesting to see whether the islands important for λM-ED island species are similar to those we identified in the global EDGE analysis. We also need to discuss GE and how best to handle this additional information. We already know we can be so much more effective in conservation when a targeted approach is taken, particularly for critically endangered species (Brooke et al. 2008).

References

Barnosky AD, Matzke N, Tomiya S, Wogan GO, Swartz B, Quental TB et al (2011) Has the Earth’s sixth mass extinction already arrived? Nature 471(7336):51–57

Bennett PM, Owens IP (1997) Variation in extinction risk among birds: chance or evolutionary predisposition? Proc R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci 264(1380):401–408

Brook BW, O’Grady JJ, Chapman AP, Burgman MA, Akçakaya HR, Frankham R (2000) Predictive accuracy of population viability analysis in conservation biology. Nature 404(6776):385–387

Brooke MDL, Butchart SHM, Garnett ST, Crowley GM, Mantilla‐Beniers NB, Stattersfield AJ (2008) Rates of movement of threatened bird species between IUCN Red List categories and toward extinction. Conserv Biol 22(2):417–427

Brooks TM, Pimm SL, Collar NJ (1997) Deforestation predicts the number of threatened birds in insular Southeast Asia. Conserv Biol 11(2):382–394

Cardillo M, Gittleman JL, Purvis A (2008) Global patterns in the phylogenetic structure of island mammal assemblages. Proc R Soc B 275(1642):1549–1556. doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.0262

Channell R, Lomolino MV (2000) Dynamic biogeography and conservation of endangered species. Nature 403:84–86

Collen B, Turvey ST, Waterman C, Meredith HM, Kuhn TS, Baillie JE, Isaac NJ (2011) Investing in evolutionary history: implementing a phylogenetic approach for mammal conservation. Philos Trans R Soc B 366(1578):2611–2622

Davies RG, Orme CDL, Storch D, Olson VA, Thomas GH, Ross SG, …, Gaston KJ (2007) Topography, energy and the global distribution of bird species richness. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 274(1614):1189–1197

Diamond JM (1974) Colonization of exploded volcanic islands by birds: the supertramp strategy. Science 184(4138):803–806

Diamond JM (1975) The island dilemma: lessons of modern biogeographic studies for the design of natural reserves. Biol Conserv 7(2):129–146

Frankham R (1998) Inbreeding and extinction: island populations. Conserv Biol 12(3):665–675

Gillespie TW, Foody GM, Rocchini D, Giorgi AP, Saatchi S (2008) Measuring and modelling biodiversity from space. Prog Phys Geogr 32(2):203–221

Hanski I (1998) Metapopulation dynamics. Nature 396(6706):41–49

Hanski I, Ovaskainen O (2000) The metapopulation capacity of a fragmented landscape. Nature 404(6779):755–758

Hanski I, Ovaskainen O (2002) Extinction debt at extinction threshold. Conserv Biol 16(3):666–673

Hanski I, Simberloff D (1997) The metapopulation approach, its history, conceptual domain, and application to conservation. In: Hanski I, Simberloff D (eds) Metapopulation biology: ecology, genetics, and evolution. Academic, San Diego

Hastings A (2010) Timescales, dynamics, and ecological understanding 1. Ecology 91(12):3471–3480

Isaac NJB, Redding DW, Meredith HM, Safi K (2012) Phylogenetically-Informed Priorities for Amphibian Conservation. PLoS ONE 7(8), e43912. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043912

Isaac NJ, Turvey ST, Collen B, Waterman C, Baillie JE (2007) Mammals on the EDGE: conservation priorities based on threat and phylogeny. PLoS One 2(3):e296

IUCN (2013) The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Version 2013.2. http://www.iucnredlist.org. Downloaded on 25 Nov 2013

Kearney M, Porter W (2009) Mechanistic niche modelling: combining physiological and spatial data to predict species’ ranges. Ecol Lett 12(4):334–350

Kerr JT, Ostrovsky M (2003) From space to species: ecological applications for remote sensing. Trends Ecol Evol 18(6):299–305

Kier G, Kreft H, Lee TM, Jetz W, Ibisch PL, Nowicki C, …, Barthlott W (2009) A global assessment of endemism and species richness across island and mainland regions. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106(23):9322–9327

Leary T, Seri L, Wright D, Hamilton S, Helgen K, Singadan R, Menzies J, Allison A, James R, Dickman C, Lunde D, Aplin K, Flannery T, Woolley P (2008) Myoictis wallacei. In: IUCN 2013. IUCN Red List of threatened species. Version 2013.2. www.iucnredlist.org. Downloaded on 30 May 2014

Loehle C, Eschenbach W (2012) Historical bird and terrestrial mammal extinction rates and causes. Divers Distrib 18(1):84–91

Losos JB, Ricklefs RE (2009) Adaptation and diversification on islands. Nature 457(7231):830–836

MacArthur RH, Wilson EO (1963) An equilibrium theory of insular zoogeography. Evolution 17(4):373–387

MacArthur RH, Wilson EO (1967) The equilibrium theory of island biogeography. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Manne LL, Brooks TM, Pimm SL (1999) Relative risk of extinction of passerine birds on continents and islands. Nature 399:258–261

Martin LJ, Blossey B, Ellis E (2012) Mapping where ecologists work: biases in the global distribution of terrestrial ecological observations. Front Ecol Environ 10(4):195–201

Moilanen A (2007) Landscape zonation, benefit functions and target-based planning: unifying reserve selection strategies. Biol Conserv 134(4):571–579

Moilanen A, Franco AM, Early RI, Fox R, Wintle B, Thomas CD (2005) Prioritizing multiple-use landscapes for conservation: methods for large multi-species planning problems. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 272(1575):1885–1891

Moilanen A, Wilson KA, Possingham HP (eds) (2009) Spatial conservation prioritization: quantitative methods and computational tools. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Ovaskainen O, Hanski I (2003) How much does an individual habitat fragment contribute to metapopulation dynamics and persistence? Theor Popul Biol 64(4):481–495

Pereira HM, Navarro LM, Martins IS (2012) Global biodiversity change: the bad, the good, and the unknown. Ann Rev Environ Resour 37:25–50

Pimm SL, Russell GJ, Gittleman JL, Brooks TM (1995) The future of biodiversity. Sci AAAS Wkly Pap Ed 269(5222):347–349

Purvis A, Gittleman JL, Cowlishaw G, Mace GM (2000) Predicting extinction risk in declining species. Proc R Soc Lond B 267:1947–1952

Ricketts TH, Dinerstein E, Boucher T, Brooks TM, Butchart SH, Hoffmann M, …, Wikramanayake E (2005) Pinpointing and preventing imminent extinctions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102(51):18497–18501

Safi K, Armour-Marshall K, Baillie JE, Isaac NJ (2013) Global patterns of evolutionary distinct and globally endangered amphibians and mammals. PLoS One 8(5):e63582

Schnell JK, Harris GM, Pimm SL, Russell GJ (2013a) Estimating extinction risk with metapopulation models of large-scale fragmentation. Conserv Biol 27(3):520–530

Schnell JK, Harris GM, Pimm SL, Russell GJ (2013b) Quantitative analysis of forest fragmentation in the Atlantic forest reveals more threatened bird species than the current Red List. PLoS One 8(5):e65357

Simberloff DS, Wilson EO (1970) Experimental zoogeography of islands. A two-year record of colonization. Ecology 51(5):934–937

Steadman DW (1995) Prehistoric extinctions of Pacific island birds: biodiversity meets zooarchaeology. Science 267(5201):1123–1131

TIB Partners (2012) Threatened island biodiversity database. Version 2012.1. http://www.tib.islandconservation.org. Downloaded on Oct 2013

Wessel P, Smith WHF (1996) A global, self-consistent, hierarchical, high-resolution shoreline database. J Geophys Res 101(B4):8741–8743

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Bart Kranstauber for discussions, and Laura J. May-Collado, Roseli Pellens, and an anonymous reviewer for helpful feedback.

Open Access This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License, which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 2.5 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/) which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the work’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if such material is not included in the work’s Creative Commons license and the respective action is not permitted by statutory regulation, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to duplicate, adapt or reproduce the material.

Copyright information

© 2016 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Schnell, J.K., Safi, K. (2016). Metapopulation Capacity Meets Evolutionary Distinctness: Spatial Fragmentation Complements Phylogenetic Rarity in Prioritization. In: Pellens, R., Grandcolas, P. (eds) Biodiversity Conservation and Phylogenetic Systematics. Topics in Biodiversity and Conservation, vol 14. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-22461-9_16

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-22461-9_16

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-22460-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-22461-9

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)