Abstract

According to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, Article 19, “children have the right to be protected from being hurt and mistreated, physically or mentally.” The 2030 UN Sustainable Development Goal 16 target 16.2 (“end abuse and violence against children”) aims toward the elimination of corporal punishment of children. Physical punishment by parents (and others) is banned by law in a growing number of countries. This chapter explores if girls are more affected by the violent family context than boys, and if countries where corporal punishment is banned do have lower level of parental maltreatment of children. We analyze data from Belgium, Denmark, Italy, and the USA collected among 12–16 year-old adolescents (n = 10,216) as part of the third sweep of the International Self-Report Delinquency survey (ISRD3) to answer the question of whether the association between troubled family life, use of violence by parents, attachment to parents, and subjective wellbeing (happiness) is different for girls than for boys, and whether it is contingent on national context. The findings suggest that gender and national context indeed do matter. We conclude the chapter with an expression of two concerns: about the universal implementation of Article 19 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child across different national contexts, and, likewise, about the challenge of promoting a Culture of Lawfulness so the children of the next generation will be happier than the present one.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

For a comprehensive overview of the norms and standards and other intergovernmental work on violence against women, see https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women/global-norms-and-standards.

- 2.

- 3.

Physical discipline, also known as corporal punishment, refers to “any punishment in which physical force is used and intended to cause some degree of pain or discomfort, however light.”

It includes acts such as kicking, pinching, spanking, shaking or throwing children, hitting them with a hand or implement (such as a whip, stick, belt, shoe or wooden spoon) or forcing them to ingest something. Violent psychological discipline involves the use of verbal aggression, threats, intimidation, denigration, ridicule, guilt, humiliation, withdrawal of love or emotional manipulation to control children.

- 4.

ISRD1 was carried out in 1991–1992 and ISRD2 in 2006–2008.

- 5.

For more information, see www.northeastern.edu/isrd/.

- 6.

There is one exception: in Table 3, we make use of findings for the 27 countries for which full data are currently available and the total sample approaches 63,000 young people.

- 7.

Transforming the original scale into POMPs (Percentage of Maximum Possible Scores) ranging from 0 to 100, makes it easier to compare between differently-scaled variables (Cohen et al. 1999).

- 8.

Ordinary least squares (OLS) regression is a statistical method of analysis that estimates the relationship between one or more independent variables and a dependent variable. We follow the common recommendation that in terms of providing the clearest interpretation of interaction terms and reliable/stable coefficients, OLS is the currently best way to analyze interactions.

- 9.

The interaction graph presents the mean predicted scores at the three levels of parental violence and for the boys and the girls resulting from a regression. We plug in the parental violence (1, 2, or 3) and the gender values (1 or 0) to get the predicted happiness value. For example, you “select” the cases of 1 in for the male variable and 2-say-for parental violence and calculate the mean predictions of those cases; then the same thing for the next: 0 for the male variable and 2 for the parental violence and calculate the mean predictions of those cases, and so on for the other four situations. The six points in the graph are the means of those predictions.

- 10.

Please note that the interaction graphs do not include the larger number of variables of the OLS models. However, the beta coefficient of 0.73*** for the interaction parental violence*gender in the full model (Table 4) provides additional evidence for the differential gender impact of parental violence on happiness.

- 11.

It should be noted that the interpretation of the magnitude of the effect of parental violence needs to be approached with caution, since the OLS models do include interaction terms involving parental violence. In the view of some, the interpretation of lower order terms in the presence of an interaction term is complex and is generally avoided (Braumoeller 2004).

- 12.

Considering that the USA is known as an exceptionally violent country (compared to most European countries) with a high level of gun-related violence including mass shootings, suicides, and gang-related violence), it is actually surprising that the level of parental violence in the current study was only marginally higher in the US sample than in the other three samples. This likely reflects the composition of the sample and the method of data collection (school-based self-report surveys).

References

Afifi, T. O., Brownridge, D. A., Cox, B. J., & Sareen, J. (2006). Physical punishment, childhood abuse and psychiatric disorders. Child Abuse and Neglect, 30(10), 1093–1103.

Braumoeller, B. (2004). Hypothesis testing and multiplicative interaction terms. International Organization, 58(4), 807–820.

Cohen, P., Cohen, J., Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1999). The problem of units and the circumstance for POMP. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 34, 315–346.

Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Ryan, K. (2013). Universal and cultural differences in the causes and structure of “happiness” – A multilevel review. In C. Keyes (Ed.), Mental well-being: International contributions to the study of positive mental healths (pp. 153–176). Dordrecht: Springer.

Endendijk, J. J., Groeneveld, M. G., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Mesman, J. (2016). Gender-differentiated parenting revisited: Meta-analysis reveals very few differences in parental control of boys and girls. PloS one, 11(7), e0159193. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159193

Enzmann, D., Kivivuori, J., Marshall, I. H., Steketee, M., Hough, M., & Killias, M. (2018). A global perspective on young people as offenders and victims: First results from the ISRD3 Study. New York: Springer.

Finkelhor, D., Turner, H., Ormrod, R., Hamby, S., & Kracke, K. (2019). Children’s exposure to violence: A comprehensive Natiopnal survey. Juvenile Justice Bulletin, October 2009.

Gershoff, E. T. (2010). More harm than good: A summary of scientific research on the intended and unintended effects of corporal punishment on children. Law and Contemporary Problems, 73, 31.

Gershoff, E. T. (2018). Corporal punishment associated with dating violence. Journal of Pediatrics, 198, 322–325.

Gershoff, E. T., & Font, S. A. (2016). Corporal punishment in US public schools: Prevalence, disparities in use, and status in state and federal policy. Social Policy Report, 30, 1–26.

Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children. (2015). Prohibiting and eliminating violent punishment of girls: A key element in guaranteeing the health and safety of women and girls worldwide. London: Global Initiative to End All Coprporal Punishment of Children.

Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children. (2017). Corporal punishment of children in Denmark. London: Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children.

Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children. (2019a). Corporal punishment of children in Belgium. London: Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children.

Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children. (2019b). Corporal punishment of children in Italy. London: Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children.

Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children. (2019c). Global Report 2018: Progress towards ending corporal punishment of children. London: Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children.

Hagan, J., Schoenfeld, H., & Palloni, A. (2006). The science of human rights, war crimes, and humanitarian emergencies. Annual Review of Sociology, 32(1), 329–349. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.32.061604.123125

Hofmann, W., Luhmann, M., Fisher, R. R., Vohs, K. D., & Baumeister, R. F. (2013). Yes, but are they happy? Effects of trait self-control on affective well-being and life satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 265–277.

Holder, M. D. (2012). Happiness in children. Measurement, correlates and enhancement of positive subjective well-being. New York: Springer.

Ipsos Public Affairs. (2012). I metodi educative e il ricorso a punizioni fisiche. Paris: Ipsos Public Affairs.

Karstedt, S. (2012). Mass Atrocities. Annual Review of Law and Social Science. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-102612-134016

Keyes, K., Leray, E., Pez, O., Bitfoi, A., Koç, C., Goelitz, D., et al. (2015). Parental use of corporal punishment in Europe: Intersection between public health and policy. PloS one, 10(2), e0118059.

Lansford, J. E., Alampay, L. P., Al-Hassan, S., Bacchini, D., Bombi, A. S., Bornstein, M. H., et al. (2010). Corporal punishment of children in nine countries as a function of child gender and parent gender. International Journal of Pediatrics, 2010, 1–12.

Lansford, J. E., Sharma, C., Malone, P. S., Woodlief, D., Dodge, K. A., Oburu, P., et al. (2014). Corporal punishment, maternal warmth, and child adjustment: A longitudinal study in eight countries. Journal of Clinical Child Adolescent Psychology, 43(4), 670–685.

Marshall, I. H., & Enzmann, D. (2012). Methodology and design of the ISRD-2 study. In J. Junger-Tas, I. H. Marshall, D. Enzmann, M. Killias, M. Steketee, & B. Gruszczynska (Eds.), The many faces of youth crime. Contrasting theoretical perspectives on Juvenile Delinquency across Countries and cultures (pp. 21–65). New York: Springer.

Paternoster, R., Brame, R., Mazerolle, P., & Piquero, A. (1998). Using the correct statistical test for the equality of regression coefficients. Criminology, 36(4), 859–866.

Romney, A. K., Weller, S. C., & Batchelder, W. H. (1986). Culture as consensus: A theory of culture and informant accuracy. American Anthropologist, 88(2), 313–338.

Sachs, J. (2012). Introduction. In J. Helliwell, R. Layard, & J. Sachs (Eds.), World happiness report. New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

Savelsberg, J. (2010). Crime and human rights: Criminology of genocide and atrocities. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

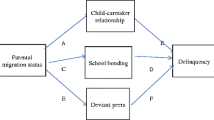

Steketee, M., Aussems, C., & Marshall, I. (2019). Exploring the impact of child maltreatment and interparental violence on violent delinquency in an international sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 088626051882329-undefined. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518823291

Tankebe, J., & Liebling, A. (2013). Legitimacy and criminal justice: An international exploration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2019). Quick facts Massachusetts (2019 ed.). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

UNICEF. (2011). Nordic study on child rights to participate 2009–2010. UNICEF: Innolink Research.

United Nations. (2013). Happiness: towards a holistic approach to development. Note by the Secretary-General. (Vol. A/67/697).

United Nations. (2015). Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 17 December 2015. Doha declaration on integrating crime prevention and criminal justice into the wider United Nations agenda to address social and economic challenges and to promote the rule of law at the national and international levels, and public participation A/RES/70/74.

United Nations Children’s Fund. (2014). Hidden in plain sight: A statistical analysis of violence against children. New York: eSocialSciences.

Wexler, A. (2018). Don’t worry, be happy! The importance of furthering the study of happiness in the field of criminal justice. Boston: Northeastern University.

Widom, C. S., & Wilson, H. W. (2015). Intergenerational transmission of violence. In Violence and mental health (pp. 27–45). New York: Springer.

World Health Organization (WHO). (1946). Constitution of the World Health Organization. Basic documents. Geneva: World Health Organization.

World Population Review. (2019). Colorado Population. http://worldpopulationreview.com/states/colorado/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Marshall, I.H., Wills, C., Marshall, C.E. (2021). Parents Who Hit, Troubled Families, and Children’s Happiness: Do Gender and National Context Make a Difference?. In: Kury, H., Redo, S. (eds) Crime Prevention and Justice in 2030. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-56227-4_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-56227-4_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-56226-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-56227-4

eBook Packages: Law and CriminologyLaw and Criminology (R0)