Abstract

Homelessness in later life is closely related to social exclusion and can cause further disadvantages in later life. This chapter explores the relationship between studies on older adult homelessness and the domains of social exclusion. A structure review process, in the form of a summative content analysis and a social network analysis, of all geriatrics and gerontology journals published in English was conducted. This review led to the identification of 59 articles on homelessness in older age as the research sample for this chapter. The patterns that emerged from summative content analysis and the social network analysis are visualised using GEPHI software. Our findings reveal the multidimensional aspects of old-age exclusion in the homelessness literature, and how homelessness can be a significant determinant of interrelated sets of disadvantages. Exclusion from services, amenities, and mobility and community and neighbourhood, and material and financial resources are the domains represented most in homelessness studies in the ageing literature. However, civic participation and socio-cultural aspects of social exclusion were partly ignored within this body of work.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Homelessness is a contemporary phenomenon that has emerged in all modern societies, due to individual and structural factors regardless of the level of a nation’s wealth. Homeless individuals are described as people sleeping on the streets, in temporary shelters and those who live in precarious housing (Crane and Warnes 1997; Craig and Timms 2000; Zufferey and Kerr 2004). Several different terms such as “homeless” “rough sleepers” and “street people” are used in the literature. As such, the diversity of the terms used can be problematic when defining the focus and scope of research and indeed participant selection on the topic. Independent of the definition used, homelessness creates disadvantages such as poverty, exclusion, victimisation, abuse, susceptibility to diseases and an inability to access services. Homeless people are not homogenous, they may have different features, different backgrounds and distinct needs. Age is an important factor affecting the needs and conditions of homeless groups. Older homeless, as a part of a new ageing population, are increasing in number and facing more disadvantages compared to other age groups experiencing homelessness. Recent restrictions in social welfare policies, increasing poverty rates and lack of appropriate housing supply have made homelessness more visible amongst older people, which in turn has resulted in an increase in research on homelessness in later life (Warnes and Crane 2000; Anderson 2003; Woolrych et al. 2015).

Grenier et al. (2016a) revealed in their literature review that homelessness is defined in the literature as encompassing three different groups. First, transitional homeless are individuals who live in shelters for less than 1 month. This group consists of younger individuals with less physical and mental health, and addiction problems compared to other homeless groups. Second, episodically homeless are mainly young individuals with high levels of mental and physical health, and addiction problems. This group use shelters periodically and often end up staying in hospitals, prisons, detoxification centres and on the streets. Third, chronically homeless are often older individuals who need shelter for longer periods, and who have more disabilities compared to other groups. The possibilities to turn back to work or find a new job is more difficult compared to younger individuals, with unemployment significantly contributing to the higher proportion of older adults (those 50 years and over) chronically homeless (Caton et al. 2005; Grenier et al. 2016b).

Alcohol and drug addiction, mental health problems, family conflicts, domestic violence, street culture, prostitution, imprisonment, begging, street-level drug dealing are among the extensive list of risk factors for homelessness in later life (Bowpitt et al. 2011; Fitzpatrick et al. 2013). Individuals might lose their social, physical and mental well-being as a result of the vicious cycle of deteriorating life conditions. Inability for self-help and seeking help, might increase problems cumulatively and might result in the deterioration of family relations, health and self-care permanently (Wolch et al. 1988; Rothwell et al. 2017). Besides the onset of traumatic circumstances, such as war and natural disasters, significant life changes such as loss of work and bereavement might also result in homelessness (Crane et al. 2005). However, all older individuals facing such risks do not necessarily end up as being homeless.

Older homeless adults are not a homogenous group. Fitzpatrick et al. (2011) proposed homelessness as a multidimensional form of exclusion. However, research assessing the extent of evidence linking homelessness in later life to the multidimensionality of old-age exclusion is scarce, if not non-existent. To uncover this connection, it is necessary to present how social exclusion, as a multidimensional concept, and homelessness in later life are connected in the international scientific literature. This research aims to reveal the intensity of the intersectional patterns of multidimensionality of old-age exclusion and homelessness in the ageing literature and to visualise these cross-sectional patterns, which can point to the possible interrelationships between different forms of disadvantage for older homeless adults.

We will begin by reviewing the general literature on older adult homelessness, including key determinants and risk factors, and will present an overview of the representation of social exclusion in research on homelessness. We will then outline our methodological approach to reviewing the literature. This is followed by a presentation of our analysis of exclusion and homelessness in the ageing literature.

2 Homelessness in Older-Age and Multidimensional Social Exclusion

Homelessness in old-age first began to emerge as a research topic in the 1980s with the changes in social welfare policies, and the scientific interest in homelessness in later life has been growing since. One strand of literature focused on the impact of rough living conditions associated with homelessness on the ageing process. Some researchers draw attention to higher prevalence of chronic diseases and disabilities among older homeless adults as well as to lower opportunities of re-entering the labour force (Cohen et al. 1988; Crane et al. 2005; Shinn et al. 2007). Another strand of literature focuses on earlier experiences of older homeless adults. Researchers reveal that older homeless individuals can sometimes possess devastating childhood experiences, addictions or mental health problems (Susser et al. 1993; Herman et al. 1997; Caton et al. 2000). Susser et al. (1993) assert the cumulative risk factors at different stages of life in relation to homelessness in old-age. Research shows that a lower education profile, a history of imprisonment, poverty and violence at younger age adds to traumatic life transitions and increases the possibility of being homeless in later life (Metraux and Culhane 2006; Grenier et al. 2016b). Moreover, life transitions in older-age such as widowhood, loss of next of kin, divorce, loss of work and poverty were also highlighted as factors specific for older homelessness (Crane and Warnes 1997; Cohen 1999; Norman and Pauly 2013).

The older homeless population are particularly of interest due to the complexity and distinctiveness of their needs. The need for proper nutrition and care increases with older-age, as well as the need for adequate and safe residential conditions (Johnson and McCool 2003; Abbott and Sapsford 2005). Older homeless adults, especially older women and transgender individuals, are also more likely to be prone to being victims of crime (Cohen et al. 1992; Salem et al. 2014; Grenier et al. 2016b). While older homeless individuals are more vulnerable to diseases, health services are difficult to access for this group. Therefore, health care needs of older homeless adults are often not sufficiently addressed (Power and Hunter 2001). This is compounded by their reluctance to request or access services and other benefits (Watson et al. 2016). Older homeless adults are reluctant to stay in shelters because of crowd, noise and fear of violence. Warnes and Crane (2000) highlights that even though the services targeting older homeless have been improved in the US and Australia since 1980s, older homeless individuals as a distinct group are not widely acknowledged in policy and practice. Factors suggested to be driving this lack of awareness include the priority often given to younger homeless populations and the deficiencies in the reporting of homelessness in later life.

Researchers have increasingly looked to adopt social exclusion as a concept in homelessness research (Kennett 1999; Anderson 2003). Social exclusion and homelessness can be considered mutually nurtured. Social exclusion is described as the deficiency of accessing different resources such as financial resources, services, social relations, and participation in society, causing inequality. Exclusion from each of these resources constitute social exclusion as a multidimensional process. According to Horsell (2006), social exclusion occurs in three processes: disadvantages related to social, economic and political conditions; the process of disadvantage; and the outcome of processes of marginalisation. Social and economic struggles might cause homelessness; during homelessness support systems and resources may diminish; and lastly individuals may become prone to marginalisation and stigmatisation (Norman and Pauly 2013).

3 Method

The main question that the research targets to address gaps concerning the connections between social exclusion and homelessness is: How are old-age exclusion domains represented in the older homelessness literature?

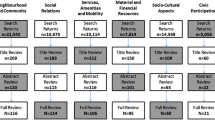

The first step of the research involved determining the sample selection criteria. The main inclusion/exclusion criteria were: peer-review articles in geriatrics and gerontology journals published in English: articles focused on older adults (50 years and over); articles focused on homelessness. Research posters, research reports and grey literature were excluded. All gerontology and geriatrics journals were searched for this material. The SCImago Journal & Country Rank portal enables access to all journals relevant to geriatrics and gerontology. In total, 105 journals were extracted, however, 10 were excluded as they were non-English journals. The key words: “homeless”, “street people”, and “rough sleepers” were used for the title review. Out of the 95 journals, 59 articles (across 25 journals) were found to be relevant to homelessness in old-age. Accordingly, these 59 articles were adopted as the final research sample. The review was carried out from September 2018 to August 2019.

The structured review process consists of two phases; a summative content analysis (SCA) and a social network analysis (SNA). SCA is a form of qualitative analysis that helps to quantify keywords to comprehend the focus of the content (Hsieh and Shannon 2005). In the research, SCA is employed to identify how intensely articles on homelessness concentrate on the domains of social exclusion. In contrast, SNA is an interdisciplinary method to analyse a wide range of subjects such as kinship structures, science citations, and contacts among members (Scott 1988). In this chapter, SNA is used to reveal the patterns and trends of the dataset between articles and social exclusion domains. To provide an example: while article A might have keywords under neighbourhood and community and social relations domains, article B might have keywords under all domains. SNA enables the visualisation of multiple relations of multiple factors concurrently. SNA also assists the development of a network visualization to simplify the complexity of links between social exclusion domains and the networks of different articles constituting the research sample in this research. The reason why this chapter has adopted SCA and SNA is that classical review techniques would not fully facilitate the sort of elaboration on interconnections and relationships that can be ascertained and visualised using these methods.

Old-age exclusion has a multidimensional nature including multiple domains. Therefore, social exclusion domains must be determined in order to reveal social exclusion patterns in the homelessness literature. Walsh et al. (2017) classify the exclusion domains as: (1) neighbourhood and community; (2) social relations; (3) services, amenities, and mobility; (4) material and financial resources; (5) socio-cultural aspects of society, and (6) civic participation. Each domain is represented by domain-specific words (see Table 26.1). Those keywords determined by Walsh et al. (2017) have been used for the summative content analysis in this research. Frequencies of domain specific key words were counted for each domain, and the intensity of each domain was extracted for multidimensionality, using a data-charting form created in Microsoft Excel.

Data was imported into Gephi – the Yifan Hu Proportional algorithm for visualisation. Data visualization depicted the intensity to which articles address the social exclusion domains.

3.1 Limitations

The research sample consists of gerontology and geriatrics journals published in English only. Related articles in journals outside of this field, books and research reports, and journals published in other languages were excluded.

4 Findings

4.1 Sample Characteristics

Out of the 59 articles identified from 25 journals, The Gerontologist (n = 15) was the dominant publication source. Articles were published on this topic from 1961–2019. Yet, no article was published between 1961 and 1983. Assuming Lovald’s review (1961) was an exception, it would not be wrong to say that homelessness became a research interest in parallel with the emergence of restrictions in housing and social policies and global demographic ageing patterns during the 1980s (Grenier et al. 2016a) and this trend was accelerated in 2000s due to a rising interest in global ageing (Fig. 26.1).

Factors causing homelessness and the concept of homelessness was discussed the most (n = 16) in old-age homelessness research. Reflecting the range of risk factors associated with homelessness, and the ambiguity surrounding the concept itself, it is not surprising that these topics were most evident within the reviewed literature.

Homelessness and health was the second most common theme (n = 15), and is likely to be due to the higher incidence of diseases in older-age for homeless individuals. The remaining papers comprised topics related to services for homelessness such as health care and meal provision (n = 11), shelters such as emergency and temporary housing (n = 9) and coping strategies and planning for special needs (n = 4). The least discussed subjects were mortality, addictions, socio-cultural aspects and nutrition, with only one article on each of these subjects.

4.2 Old-Age Exclusion Domains in Homelessness Literature

Summative content analysis was conducted to reveal the connections of old-age exclusion domains in the sample. Domain specific keywords constituting each domain have been counted for all 59 articles and the total number of domain specific key words was found to be n = 2685. Approximately half of the articles about homelessness in the gerontology and geriatrics literature referred to the services, amenities and mobility domains of social exclusion and about a quarter referred to the neighbourhood and community domains. Social relations, material and financial resources, socio-cultural aspects of society, and civic participation domains comprised the remaining quarter (see, Fig. 26.2).

The domain specific keywords of all six old-age exclusion domains were counted separately, after revealing the distribution of domains of old-age exclusion. “Service”, was the most frequent identified domain specific keyword (n = 1085; 40.4%). Followed by community (n = 366; 13.6%), place (n = 177; 6.6%), utilisation (n = 111; 4.1%), poverty (n = 108; 4.1%), financial resources (n = 87; 3.2%); isolation (n = 70; 2.6%), neighbourhood (n = 57; 2.2%), and social network (n = 45; 2%). The remaining 27 keywords were present in less than 2 per cent, of articles. The least repeated words were the ones representing the socio-cultural aspects of social exclusion.

5 Multidimensionality

In order to determine multidimensionality, two categories were established; related and unrelated. In the absence of domain specific keywords, the article was coded as unrelated. On the other hand, if one or more domain specific keywords existed in the article, it was coded as related. Domain specific keywords in all the articles were counted for all the domains separately and all were found to be related to one or more old-age exclusion domains. Eleven articles (18.6%) were found to be related to all six domains. Twenty (33.9%) were related to five domains, sixteen (27.1%) to four domains, ten (16.9%) to three domains. None of the articles were relevant to two domains and only two (3.4%) were relevant to one domain. Almost all articles (n = 58; 98.3%) were related to services, amenities, and mobility. Fifty-six articles (94.9%) were linked to neighbourhood and community, 50 articles (84.7%) were related to material and financial resources, 37 articles (62.7%) were related to social relations, 33 articles (55.9%) were related to socio-cultural aspects of society and 28 articles (47.4%) were related to civic participation (see, Table. 26.2).

Services, amenities, mobility and neighbourhood and community domains represent the main trends in older homelessness literature. All articles, except one (which had only one network), had two or more networks with old-age exclusion domains, 11 articles had networks with all domains, 20 articles had networks with five domains, 16 articles with four, 10 articles with three and 2 articles with only one domain. This finding might reveal the multidimensional nature of social exclusion and homelessness. This multidimensionality has resulted with multiple networks as it is difficult to isolate in social exclusion and homelessness research one domain only.

5.1 Multidimensional Patterns of Old-Age Exclusion

The data discussed above gathered from the summative content analysis revealed the multidimensionality of old-age exclusion. However, it did not reveal the density of the connection between articles and old-age exclusion domains virtually. In order to illustrate these connections, social network analysis was conducted and the pattern obtained was visualised using GEPHI software (Fig. 26.3).

Edge and Node matrixes were used to import the data to GEPHI. In this research, nodes were identified as network members (59 articles and six old-age exclusion domains). Edges were identified as a network showing the connection of the literature with old-age exclusion domains. The thickness of the edge (line) was directly related with the frequency of network members. A thicker edge was indicating a higher frequency of old-age exclusion domains in articles. These matrixes were created in Excel and were imported into GEPHI. There were 65 nodes (59 articles and six social exclusion domains) and 263 edges (total number of the connections between articles and social exclusion domains). To visualise this data, the Yifan Hu Proportional algorithm in GEPHI was applied.

The sum of all frequencies identified the weight of nodes regarding old-age exclusion domains. The old-age exclusion domain nodes grew and located towards the centre with increasing frequency. While article nodes with lower frequencies were more decentralised and heterogeneous, article nodes with multiple connections with the old-age exclusion domain nodes and with a higher frequency represented stronger connections with the network and the pattern of network was more centralised in the resulting figure (see Fig. 26.3).

Figure 26.3 enabled a clear visualisation of the least and most addressed old-age exclusion domains in the old-age homelessness literature according to the size of nodes and thickness of edges. The most centralised zone in the figure was services, amenities and mobility. The nodes representing neighbourhood and community, and material and financial resources are located near the centre. These three domains were partially positioned in the centre, constituting the old-age exclusion domain with the highest density regarding homelessness. Socio-cultural aspects and civic participation however were found to have the least density and were located further from the centre.

6 Conclusion

Homeless older adults are among the main groups exposed to social exclusion. Older homeless individuals are more vulnerable in terms of social exclusion compared to homeless adults of other age groups. The disadvantages of older homeless is discussed in the literature (Sullivan 1991; Burns and Sussman 2018). Researchers focused on the prevention of exclusion by proper service provision and revealed that the deficiency in support systems increases the risk for older homelessness (Warnes and Crane 2000; Manthorpe et al. 2013). The high frequency of the domain of services, amenities, and mobility found in this research can be explained in connection with this. Research articles were concentrating on service provision gaps mainly for health and social services.

The multidimensionality of old-age exclusion in homelessness literature appeared partly in this research, focused on services, amenities and mobility; neighbourhood and community and material and financial resources domains. These domains were found to be interconnected according to SNA analysis. Socio-cultural aspects of society, civic participation and social relations exclusion domains however were less frequently researched.

Even though the articles comprising the sample in this research were specifically on homelessness in older-age but not on old-age exclusion, old-age exclusion domains were strongly prevalent in all articles. These findings show clearly that homelessness in old-age is crossing social exclusion ontologically. Parallel to our result, homelessness experiences in old-age were discussed as a social exclusion process, concentrating on problems and solutions. The reasons that this was the case however could not be highlighted. It is not possible to address multidimensionality in old-age homelessness research unless political, economic and social macro processes causing exclusion are addressed. Old-age homelessness is a worldwide phenomenon and the number of old-age homeless is increasing due to the rising cost of housing, global economic and localised recessions, poverty and global ageing. This trend is expected to be reflected in the international literature even more in the future.

This research has focused only on whether old-age exclusion key words exist in articles and the number of key words in each article. Accordingly, we can only conclude on frequencies and unfortunately cannot elaborate in depth about the connections between homelessness and the different domains of exclusion, the interconnection between these domains and about the impacts involved. Further research will be valuable to explore these connections in detail.

References

Abbott, P., & Sapsford, R. (2005). Living on the margins: Older people, place and social exclusion. Policy Studies, 26(1), 29–46.

Anderson, I. (2003). Synthesizing homelessness research: Trends, lessons and prospects. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 13(2), 197–205.

Bowpitt, G., Dwyer, P., Sundin, E., & Weinstein, M. (2011). Comparing men’s and women’s experiences of multiple exclusion homelessness. Social Policy and Society, 10(4), 537–546.

Burns, V. F., & Sussman, T. (2018). Homeless for the first time in later life: Uncovering more than one pathway. The Gerontologist, 59(2), 251–259.

Caton, C. L., Hasin, D., Shrout, P. E., Opler, L. A., Hirshfield, S., Dominguez, B., & Felix, A. (2000). Risk factors for homelessness among indigent urban adults with no history of psychotic illness: A case-control study. American Journal of Public Health, 90(2), 258.

Caton, C. L., Dominguez, B., Schanzer, B., Hasin, D. S., Shrout, P. E., Felix, A., et al. (2005). Risk factors for long-term homelessness: Findings from a longitudinal study of first-time homeless single adults. American Journal of Public Health, 95(10), 1753–1759.

Cohen, C. I. (1999). Aging and homelessness. The Gerontologist, 39(1), 5–15.

Cohen, C. I., Teresi, J. A., & Holmes, D. (1988). The physical well-being of old homeless men. Journal of Gerontology, 43(4), 121–128.

Cohen, C. I., Onserud, H., & Monaco, C. (1992). Project rescue: Serving the homeless and marginally housed elderly. The Gerontologist, 32(4), 466–471.

Craig, T., & Timms, P. (2000). Facing up to social exclusion: Services for homeless mentally ill people. International Review of Psychiatry, 12(3), 206–211.

Crane, M., & Warnes, T. (1997). Homeless truths: Challenging the myths about older homeless people. London: Help the Aged.

Crane, M., Byrne, K., Fu, R., Lipmann, B., Mirabelli, F., Rota-Bartelink, A., et al. (2005). The causes of homelessness in later life: Findings from a 3-nation study. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60(3), 152–159.

Fitzpatrick, S., Johnsen, S., & White, M. (2011). Multiple exclusion homelessness in the UK: Key patterns and intersections. Social Policy and Society, 10(4), 501–512.

Fitzpatrick, S., Bramley, G., & Johnsen, S. (2013). Pathways into multiple exclusion homelessness in seven UK cities. Urban Studies, 50(1), 148–168.

Grenier, A., Barken, R., & McGrath, C. (2016a). Homelessness and aging: The contradictory ordering of ‘house’ and ‘home’. Journal of Aging Studies, 39, 73–80.

Grenier, A., Barken, R., Sussman, T., Rothwell, D., Bourgeois-Guérin, V., & Lavoie, J. P. (2016b). A literature review of homelessness and aging: Suggestions for a policy and practice-relevant research agenda. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue canadienne du vieillissement, 35(1), 28–41.

Herman, D. B., Susser, E. S., Struening, E. L., & Link, B. L. (1997). Adverse childhood experiences: Are they risk factors for adult homelessness? American Journal of Public Health, 87(2), 249–255.

Horsell, C. (2006). Homelessness and social exclusion: A Foucauldian perspective for social workers. Australian Social Work, 59(2), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/03124070600651911.

Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288.

Johnson, L. J., & McCool, A. C. (2003). Dietary intake and nutritional status of older adult homeless women: A pilot study. Journal of Nutrition for the Elderly, 23(1), 1–21.

Kennett, P. (1999). Homelessness, citizenship and social exclusion. In P. Kennett & A. Marsh (Eds.), Homelessness: Exploring the new terrain (pp. 37–60). Bristol: Policy Press.

Lovald, K. A. (1961). Social life of the aged homeless man in skid row. The Gerontologist, 1(1), 30–33.

Manthorpe, J., Cornes, M., O’Halloran, S., & Joly, L. (2013). Multiple exclusion homelessness: The preventive role of social work. The British Journal of Social Work, 45(2), 587–599.

Metraux, S., & Culhane, D. P. (2006). Recent incarceration history among a sheltered homeless population. Crime & Delinquency, 52(3), 504–517.

Norman, T., & Pauly, B. (2013). Including people who experience homelessness: A scoping review of the literature. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 33(3/4), 136–151.

Power, R., & Hunter, G. (2001). Developing a strategy for community-based health promotion targeting homeless populations. Health Education Research, 16(5), 593–602.

Rothwell, D. W., Sussman, T., Grenier, A., Mott, S., & Bourgeois-Guérin, V. (2017). Patterns of shelter use among men new to homelessness in later life: Duration of stay and psychosocial factors related to departure. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 36(1), 71–93.

Salem, B. E., Nyamathi, A., Brecht, M. L., Phillips, L. R., Mentes, J. C., Sarkisian, C., & Stein, J. A. (2014). Constructing and identifying predictors of frailty among homeless adults—A latent variable structural equations model approach. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 58(2), 248–256.

Scott, J. (1988). Social network analysis. Sociology, 22(1), 109–127.

Shinn, M., Gottlieb, J., Wett, J. L., Bahl, A., Cohen, A., & Baron Ellis, D. (2007). Predictors of homelessness among older adults in new York City: Disability, economic, human and social capital and stressful events. Journal of Health Psychology, 12(5), 696–708.

Sullivan, M. A. (1991). The homeless older woman in context: Alienation, cutoff and reconnection. Journal of Women & Aging, 3(2), 3–24.

Susser, E., Moore, R., & Link, B. (1993). Risk factors for homelessness. Epidemiologic Reviews, 15(2), 546–556.

Walsh, K., Scharf, T., & Keating, N. (2017). Social exclusion of older persons: A scoping review and conceptual framework. European Journal of Ageing, 14, 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-016-0398-8.

Warnes, A. M., & Crane, M. A. (2000). The achievements of a multiservice project for older homeless people. The Gerontologist, 40(5), 618–626.

Watson, J., Crawley, J., & Kane, D. (2016). Social exclusion, health and hidden homelessness. Public Health, 139, 96–102.

Wolch, J. R., Dear, M., & Akita, A. (1988). Explaining homelessness. Journal of the American Planning Association, 54(4), 443–453.

Woolrych, R., Gibson, N., Sixsmith, J., & Sixsmith, A. (2015). “No home, no place”: Addressing the complexity of homelessness in old age through community dialogue. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 29(3), 233–258.

Zufferey, C., & Kerr, L. (2004). Identity and everyday experiences of homelessness: Some implications for social work. Australian Social Work, 57(4), 343–353.

Editors’ Postscript

Please note, like other contributions to this book, this chapter was written before the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020. The book’s introductory chapter (Chap. 1) and conclusion (Chap. 34) consider some of the key ways in which the pandemic relates to issues concerning social exclusion and ageing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Korkmaz-Yaylagul, N., Bas, A.M. (2021). Homelessness Trends in Ageing Literature in the Context of Domains of Social Exclusion. In: Walsh, K., Scharf, T., Van Regenmortel, S., Wanka, A. (eds) Social Exclusion in Later Life. International Perspectives on Aging, vol 28. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51406-8_26

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51406-8_26

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-51405-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-51406-8

eBook Packages: HistoryHistory (R0)