Abstract

Asylum seeker reception has proved something of a ‘wicked issue’, resulting in an impasse in decision-making at national and European levels, and ‘scale mismatch’ with local contexts where the problem manifests. The 2015–2016 refugee crisis provoked an opportunity for experimentation at the local level in European cities. This chapter provides an example of one such experiment: the Utrecht Refugee Launchpad, or ‘Plan Einstein’ as it is known locally, a new concept of asylum seeker reception and integration. It offered ‘futureproof’ skills development for asylum seekers and simultaneous benefits for local people from the neighbourhood through living and learning together. We discuss how the concept aimed to respond to existing challenges, how it adapted in practice and why the innovation was able to prosper at this specific moment. In particular, the chapter shows how through the development of multi-sector and multi-level alliances, the project was made appealing to different constituents for different reasons. The chapter also shows how the experiment resulted in the initiators manoeuvring within different political contexts and constraints locally and nationally. In this way, it did not challenge outright the existing structures through decoupling from the national level, but negotiated within these, to bring the concept into being.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction: Asylum Reception as a Multi-level Governance Issue

Asylum seeker reception in Europe has proven a ‘wicked issue’ (Rittel and Webber 1973), whereby policy actors identify the problem in different ways and existing policy solutions have so far failed to resolve the challenges. This became particularly clear during the 2015–2016 European ‘refugee crisis’ when various political and administrative problems with asylum reception were apparent. Agreement about the nature of the problem and desirability of solutions was difficult to reach at European and national levels of government, while achieving consensus and constructing partnership-based modes of multilevel governance between different tiers proved difficult.

In the Dutch context, as well as other European countries, there is considerable debate about the number of asylum seekers that should be admitted, as well as how the reception of such asylum seekers should take shape. This issue has been the basis of discussion for at least 30 years, while the most important arguments have not changed fundamentally (Geuijen 2004). On the one hand, there is a view that the human rights of refugees must be protected; that refugees have the right to protection from persecution and that they have civil, political and economic rights, such as the right to freedom of expression, the right to housing, to work and to health care. On the other hand, there is the view that national interests must be protected. This relates firstly to the field of economy and social security (costs of welfare, education etc.); secondly in relation to the socio-cultural field (especially around potential threats to national identity); and thirdly in the area of security (both related to general crime and more recently to terrorism). The contrasting arguments can be found in many variants in discussions on asylum that have taken place in the past three decades.

Second, in terms of content and governance, there is an impasse on the national level. The asylum problem is blamed repeatedly on the European Union, on migrant smugglers, as well as on asylum seekers themselves, some of whom are perceived as ‘abusing’ the asylum system. Politicians seem compelled to express the feelings of ‘the regular (angry) Dutch citizen’ and to leave the burden of receiving asylum seekers to those countries in Europe where asylum seekers first arrive: mostly in Italy and Greece. Within the Netherlands, we also see that asylum policies at the national level have increasingly been stripped down to a depoliticized, managerial approach to asylum reception. The Central Agency for the Reception of Asylum Seekers (COA) organizes asylum seekers’ centers, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (IND) organizes the asylum procedure, while the Repatriation and Departure Service (DT & V) organizes return and expulsions. At the same time, the asylum debate at the national level is at an impasse: there are polarized political debates in the House of Representatives and responsibilities are shifted to the European level, but on this level of governance, actors are even further away from reaching consensus.

Within this governance context, problems related to asylum reception are thereby, by default arriving at the local level. The poor socio-economic integration of refugees implies, among other things, pressure on municipalities: of having to pay for benefits, as well as solve shortages within the local social housing rental market. Problems in achieving returns lead to undocumented people living on the streets in municipalities, who then face obligations to provide ‘bed-bath-bread’ provisions for them. Dissatisfaction and protest in neighbourhoods where these problems manifest are also directed against the administration of municipalities, who must address local tensions. Yet in many ways, their hands are tied because of the ‘scale mismatch’ (Castells 2008) between the arenas in which the concrete problems are felt (the local level) and the place where these problems are discussed and managed (the national level).

The ‘refugee crisis’ of 2015–2016 exacerbated some of these problems related to asylum reception on the local level. However, as we explain in this chapter, this moment also opened up a window of opportunity (Kingdon 1984) for experimenting with new forms of asylum reception. At the national level, large policy frameworks for asylum reception are still being developed, but this created possibilities for discretion in the implementation of integration and asylum policies, which had been increasingly left to local authorities. Already before the refugee crisis, local governments had sought to take the initiative in shaping processes of asylum seeker reception and integration in their own ways, in what is termed as the ‘local turn’ in integration policies (Bak Jørgensen 2012; Scholten 2013). Across Europe, cities have been assuming a pioneering role, and some of these locally developed policy initiatives are subsequently transferred to the national level (Dekker et al. 2015). In this way, during the refugee crisis, the development of local solutions was not only a necessity, but also an opportunity that was taken by cities in various European countries.

This chapter discusses a specific policy initiative that was developed within such contexts in the Dutch city of Utrecht: the Utrecht Refugee Launchpad. This asylum centre is known colloquially as Plan Einstein, in reference to both the inspirational spirit of its namesake and its location along the Einsteindreef, a busy road in the neighborhood of Overvecht in the North of the city. Applying the concepts of multilevel governance and experimental governance, this chapter analyzes how it was possible that this initiative was able to be realized at this location and at this time. Besides the political-administrative vacuum at the European and national level of governance, and the urgency of the refugee crisis as a window of opportunity, the analysis also addresses how this local solution came about through manoeuvring by key actors of the initiative within its multilevel context.Footnote 1

2 Methodology

The chapter provides a case study of Plan Einstein as an exemplar of the type of local experiments with asylum reception which have started at several locations in the Netherlands – just as elsewhere in Europe and beyond – around the time of the European refugee crisis. In the deprived district of Overvecht in Utrecht, in late 2016, an office building was converted into an asylum seeker centre. At this location, 400 asylum seekers were expected to live together with 38 local youths. Various social activities and learning opportunities were provided to connect asylum seekers/refugees and local residents socially and professionally at the centre, as well as to help them generate new business ideas. The project sought to develop participants’ ‘futureproof’ skills that would be of benefit to them irrespective of whether their future was in the Netherlands or elsewhere. Challenging the national approach to reception, characterised by the motto to provide ‘austere but humane’ reception (Adviescommissie Vreemdelingenzaken 2013), this initiative aimed to diminish the common experience of reception as a time of limbo, boredom and passivity, to foster more self-determination among participants, and to repair asylum seekers’ ‘broken narratives’.Footnote 2 Through living and learning close to each other, all participants were expected to build relationships, gain skills, and ultimately benefit from better prospects and wellbeing, with the programme acting as a ‘launchpad’ to further success.

This case study is based on two types of data: first, an analysis of documents that was undertaken during the second half of 2017, including several versions of the plans and the subsidy application that formed the basis for Plan Einstein. Second, in the autumn of 2017 interviews were held with the involved partners of Plan Einstein and meetings, presentations and other activities were observed. This strand of the research is part of a larger research and evaluation of Plan Einstein led by RoehamptonFootnote 3 University, London and the University of Oxford (Oliver et al. 2018). Other components include monitoring of participation in courses and activities, observations of these courses and activities, interviews with asylum seekers, local residents, stakeholders and with young people living with Plan Einstein and a survey among local residents and young people living in the centre. While the analysis presented in this chapter has been member-checked by several involved partners, we cannot make definitive evaluative claims about this project before it finishes in late 2018 and the final evaluation is completed.

3 Plan Einstein: A Local Experiment

Plan Einstein advanced a new concept: an experimental form of asylum shelter that aimed to support asylum seekers in their preparations for the future, wherever they may be. That future might be in the Netherlands after being granted a residence permit, but might also in the country of origin, after rejection of the asylum application, or in a third country, after migrating on. The concept is framed around two pillars: firstly, ‘co-learning’ and secondly, ‘co-living’ of asylum seekers with local residents of Overvecht.

The co-learning pillar was filled with a variety of activities: The teaching of English language in classes, as well as instruction in entrepreneurship via courses and coaching. These occurred in a so-called ‘incubator’: a space where people who want to start a business could work on the design thereof, and where peer-to-peer coaching was available by more experienced entrepreneurs. All courses and coaching were conducted in English, on the basis that the English language can be used anywhere in the world. In the project proposal the courses and activities were called ‘future proof’, referring to how they prepared people for a future anywhere within or outside of the Netherlands. All activities were designed to be accessible to all asylum seekers from their first day in the asylum seekers reception center (asielzoekerscentrum AZC), supporting an aim that they could use their waiting time during the asylum procedure more meaningfully. The development activities would also provide a valuable addition to their curriculum vitae, so that they could be both better prepared for integration in the Netherlands following the granting of a residence permit, or would be better prepared for onward migration or return to their country of origin if their asylum request was rejected.

The courses were not only accessible to the 400 asylum seekers living in the reception center, but were also open to local residents to encourage mutual contact and co-learning. In addition, housing for local youngsters was created in one wing of the asylum seekers’ center, where studios were provided for rental by 38 young people. Youngsters were recruited to live there and had to demonstrate how they had in some way or another, a relationship with the neighbourhood of Overvecht. In setting this criteria, the project set out to pacify the often expressed objection from local residents that asylum seekers receive all sorts of facilities while local residents do not. By offering both courses and housing opportunities to asylum seekers and local residents, it would also mean that they could come into contact with each other more easily, with an expectation is that this would lead to more mutual understanding.

4 Responding to Local Problems of Asylum Reception in the Netherlands

The concept of Plan Einstein was developed to provide an answer to the most important problems that traditional asylum reception in the Netherlands was confronting. As with other places in the world, the arrival of large numbers of refugees through (forced) migration poses both immediate and longer-term problems in the Netherlands. In particular, the integration of many refugees into the labor market and housing market has proved difficult. Research into refugees who received a residence permit in the Netherlands in the 1990s shows that 20 years later only one third of them between the ages of 15 and 64 have a paid job (Engbersen et al. 2015). The prospect has not improved for recent groups: one and a half years after receiving a residence permit, 90% of the 18–64 year old Syrian and Eritrean refugees receive social benefits (CBS 2016). Moving on from the reception center (AZC) to housing on the regular housing market is also difficult for some groups, so many refugees with a residence permit stay unnecessarily long in asylum seekers’ centers, compounding the problems of the phase of asylum determination.

In addition, there are problems with deporting rejected asylum seekers to their country of origin. Many asylum seekers take up all possible opportunities for legal procedures, in order to challenge rejected applications and avoid expulsion. Some of the asylum seekers who have been rejected disappear from the asylum reception location without giving notice of where they are going; in policy terms: they leave ‘with unknown destination’. In 2017 there were more than 9000 of these individuals, in 2016 about 8000 (Dienst Terugkeer and Vertrek 2018). Many subsequently reside without documents in the Netherlands or in another European country (Leerkes et al. 2014). Other rejected asylum seekers on the other hand end up in detention for foreigners or in family reception locations with a view to deportation; in these cases however, it may be still very is difficult to deport people when they refuse to cooperate in obtaining the correct identity and travel documents through their national embassies.

A third problematic consequence of asylum migration for the Netherlands concerns the physical location where asylum reception take concrete shape. It is common that when neighbourhoods are given notice that a (large) asylum seeker center will be established, residents react negatively and protests have occurred. Such responses happened in several places in the Netherlands, including in the neighbourhood of Overvecht in Utrecht. National media reported on some of the community meetings held to provide information about the soon to be established AZCs (NOS 2016). Research shows that 90% of the Dutch would object to the arrival of a large AZC with 500 asylum seekers in the district or municipality and 50% of the Dutch object even to the a smaller AZC with 50 asylum seekers (Lubbers et al. 2006). In such contexts, we find that even individual housing cannot proceed in some instances, because safety can be jeopardized as a result of threats or worse.

A fourth and final problem with asylum reception in the Netherlands concerns the length and nature of time asylum seekers have to spend in the AZCs. Asylum seekers often stay in reception places for a long period of time, where they can only do limited types of activities. For example, they cannot formally learn Dutch and only work under specific conditions. Stress and uncertainty characterize their lives, which consists mainly of waiting for the outcome of the asylum procedure, followed by procedures for achieving family reunification and getting housing (often, as in the case of Utrecht, in a saturated local market). Their accommodation involves sharing a room with four or five others, and a kitchen and sanitation with more people provoking mutual tensions, quarrels and sometimes even violent incidents. Asylum seekers mostly have only few contacts outside of the reception center and loneliness is common (Engbersen et al. 2015; Adviescommissie voor Vreemdelingenzaken 2013).

The intention of the Plan Einstein experiment was that asylum seekers would integrate better into the Netherlands after admission and that there would therefore be fewer problems with labour market participation, in turn diminishing pressure on the municipal social benefits system. It was also the expected that rejected asylum seekers who would have gained better skills through the programme would object less to returning to their country of origin since they would feel somewhat facilitated to build a new life there. In principle, they might feel less inclined to cling to legal procedures in which they would have little chance of receiving a staying permit anyway. Plan Einstein was also intended as a response to strained relations between asylum seekers’ centers and the neighborhood, namely by linking direct benefits to the neighborhood to the asylum reception centre, both in the form of training opportunities and living opportunities. And finally, Plan Einstein was intended to make the life of asylum seekers less difficult during the reception phase by making it possible to spend their time in a meaningful way while developing a future perspective. This would be through facilitating contacts both with young people living in one wing of the center and with people outside the center, helping to reduce isolation and loneliness.

5 Shifts in the Plan

Plan Einstein is one of several local experiments to address local problems concerning asylum reception and to give substance to the national (and European) policy vacuum. However, being an experiment meant that Plan Einstein also had to adjust to changes in the context. Since the moment in early 2016 when Plan Einstein was designed as an emergency centre, the picture of increased asylum applications across Europe during the so-called ‘refugee crisis’ has changed dramatically. Particularly following the EU-Turkey ‘refugee deal’ in March 2016, the numbers of asylum applications in the Netherlands fell significantly. Indeed just as Plan Einstein was being developed in late 2016 and throughout 2017, the COA was closing down some emergency and reception centres and reducing occupancy in some other existing newly opened centres (Swai 2018).

From the outset of the project therefore, the U-RLP project team had to adapt to changing circumstances, including an ongoing delay and uncertainty around the arrival of asylum seekers to the centre. Early on in the project, from February 2017, rather than operating to full capacity, 40 young, male asylum seekers were placed at the centre. Following multiple delays, 350 asylum seekers arrived in August 2017. The delays created some challenges for partners in the early days of the project, who were seeking to fill classes and fulfil their obligations to the project plan. Plan Einstein also had to adapt its initial conception as an emergency centre which anticipated that asylum seekers would go there immediately after arriving in the Netherlands and access courses and activities ‘from day one’. The initial plan included short-term courses of 8 weeks as it was assumed that asylum seekers would be living in Plan Einstein only for relatively short time-periods. In reality, rather than starting at Plan Einstein on day one, those arriving at the centre were more diverse, including individuals and families who were at different stages of the asylum procedure, and therefore had already lived in multiple other centres. As a result, some individuals were moving quickly through the centre into resettlement, only remaining for a matter of days rather than staying for any longer period as expected, while others were staying much longer. Data from COA (through a private data request from the research team in October 2018) indicate that more than half of the people living in the residence center in fact had already obtained some type of residence permit when living at the centre, be it asylum related or through family reunification. These people already knew they would stay in the Netherlands so their aspirations were oriented to integration, including learning to speak Dutch, getting to know Dutch society and norms, as well as building a network.

The ‘futureproof’ approach of Plan Einstein (with activities in English) therefore needed some consideration as a result of the changes. The programme showed adaptability by allowing participants to follow courses at different levels, thus allowing participants to progress over longer periods of time, and by offering different elements of the business incubator program offered by a local social enterprise (Social Impact Factory SIF) as a follow up. The programme was also able to meet diverging needs of participants by situating the U-RLP offer within the broader, complementary integration facilities already operating within the city, for example offering the Dutch Taalcafé (Language café) organized by Welkom in Utrecht in the centre’s incubator space. The courses were adapted practically too to accommodate some difference in languages, with one class for mixed participants in English, one class with English-Arabic translation attended by asylum seekers only and some further translations brought in. There was also more emphasis on developing highly individualized matching and coaching activities (by SIF) to connect refugees to appropriate Dutch employers. Learning from the project suggests that flexibility and agility in response is vital, where providing different programs for different groups might be necessary to offer a truly futureproof programme.

An emerging challenge at the time of writing is that the project was committed to close at the pre-set date of November 2018, but suddenly faced the closure of the AZC prematurely in September 2018, due to operational reasons by COA. In the months preceding the closure, the outlook of certain stakeholders was – understandably – also changing. For example, the youngsters living at the premises were already looking for other housing options, and some project partners also shifted their focus towards transferability of the program to the other AZC in the city. During this time, there were inevitably some tensions around how to manage withdrawing an intervention that a range of beneficiaries have committed to and profited from (including the asylum seekers, youngsters and the neighbourhood).

6 The Realization of Plan Einstein

Plan Einstein was conceived initially by local civil servants in Utrecht, who had been working on this theme for 15 years in the city and elsewhere in the Netherlands. In doing so, they had been collaborating for some time with NGOs on these issues, including the Dutch Council for Refugees, the largest representative of asylum seekers and refugees in the Netherlands. The officials had also exchanged ideas and interesting examples with colleagues in other cities nationally and internationally for some time and were looking for opportunities to come to a ‘solution’ for the various problems in asylum reception.

In a way therefore, the ‘refugee crisis’ was perceived at the time by the Utrecht civil servants as a window of opportunity (Kingdon 1984) in which Winston Churchill’s well known adage applied: ‘Never let a good crisis go to waste.’ The preceding years had enabled them already to develop ideas about innovation in asylum reception and enter into partnerships with NGOs. They also saw, in responses to the crisis, that there was growing public support for asylum seekers, and this might be harnessed within an innovation. Indeed, while in some quarters, the public in the Netherlands and in Utrecht were hostile to asylum seekers in this period, locally there were also signs of an emerging welcoming culture. This is evident in spontaneous initiatives such as Welcome in Utrecht,Footnote 4 the Catching Cultures Orchestra,Footnote 5 and restaurant Syr.Footnote 6 During this moment, the Dutch Council for Refugees received more applications from new volunteers than were employable.

The local civil servants worked closely together with the highest ranking civil servant within local government. He gave them a personal assignment at the beginning of the ‘refugee crisis’ to develop an innovative approach through which Utrecht could take its part in asylum reception. Given this mandate, the local civil servants built partnerships with a range of NGOs, SMEs and Universities to develop a new approach, experimenting and trialling different solutions through collaborative innovation, as well as involving multiple stakeholders in learning and development.

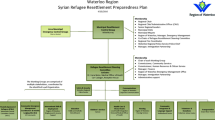

The partnership included:

-

The City of Utrecht;

-

the Dutch Refugee Council (VluchtelingenWerk West en Midden-Nederland, VWWMNFootnote 7) an NGO tasked with asylum-seeker support and brokering;

-

Socius Wonen, a housing company with a track record in creating and facilitating community living;

-

Utrecht University’s Centre for Entrepreneurship: a research institute to teach entrepreneurship;

-

The People’s University (VolksUniversiteit): an education institute, to provide English courses from basic level up to Cambridge Advanced English.

-

Social Impact Factory, a foundation stimulating social entrepreneurship, to coach participants in developing business ideas.

-

Roehampton and Oxford Universities, UK higher education institutions, to conduct an independent evaluation and share learning through international knowledge exchange.

In this way, a multisector alliance was created that jointly developed a concrete plan and sought broader support and funding for the action. Following a competitive process, the plan was co-financed through the Urban Innovative Actions (UIA) programme, a funding scheme designed to provide urban areas throughout the European Union with resources to experiment and test new and unproven solutions to solve urban challenges. This fund was created to contribute to the European urban agenda, an agenda which had already received a strong impetus under the Dutch presidency. It offered a different way of working, since the usual format for funding regional or local initiatives by the European Regional Development Fund was through dividing the budgets among the different EU countries, for decisions to be made at the national level. At the time therefore, subsidy applications from cities had to be submitted to national departments. Local officials had been lobbying for years to change this method of distribution, since they preferred for regional and local parties themselves to be able to apply for this type of EU subsidy instead of having to go through the national departments. Under the UIA funding arrangements, this now had become possible while the timing gave the Utrecht alliance the opportunity to apply directly for an EU budget without the Ministry of Justice and Security acting as gatekeeper. According to a number of stakeholders, this has made it possible for an experimental project such as Plan Einstein to receive a large EU subsidy.

Obtaining the UIA subsidy was also decisive for ameliorating financial objections from the city council. With available co-financing, different partners and stakeholders could find different strengths in the plan. The mayor, the aldermen and the City council – with a majority of D66 (liberals) and GroenLinks (green-liberals) – were sensitive to the argument that the problems in the Overvecht district could also be reduced by this initiative. The neighbourhood has high rates of unemployment and in comparison to other neighbourhoods, more residents cope with personal and social problems including in relation to health, nuisance, crime and poverty.Footnote 8 Plan Einstein could become a vibrant center that could benefit the neighborhood, while yet for these local politicians, it also offered a more humane approach to the reception of asylum seekers.

Support was also harnessed at the highest levels in local politics. The alderman politically responsible for the project (GroenLinks – green liberals) in particular felt strongly involved because the project was aimed at marginalized people: both asylum seekers and people from Overvecht. He took pride in the projection of Utrecht as a human rights city and ‘inclusive city’ and conveyed this in presentations that he regularly gave on the project, both in Utrecht and in the rest of the Netherlands and abroad. The Mayor (VVD – conservatives) was, by contrast, more interested in the entrepreneurial side of Plan Einstein, yet equally his enthusiasm also contributed to the acceptance of this type of project within his own party at local and national level.

In a similar way, the project was able to appeal to the multiple partners, who had different interests and values, because the local officials emphasized different aspects of Plan Einstein for them. For the Overvecht district – and especially neighborhood organizations – it was important that Plan Einstein offered opportunities for courses and accommodation for young people. This would be expected to help reduce the existing tensions between different groups in the neighborhood. As noted earlier, following the announcement that there would be an asylum seekers’ center in Overvecht, there had been heated meetings in the district where residents expressed strong negative reactions to the plan. They felt that there were more than enough problems in Overvecht: high unemployment, low education, a prostitution zone, people from many different cultural backgrounds, with different languages and/or different living rhythms, who have little contact with each other, but who had to live in close proximity to each other in cramped high-rise flats. The neighborhood organizations, such as the district office, were initially negative about the plans to establish an AZC in Overvecht. This was particularly because Overvecht had for 10 years been under the so-called ‘power district’ approach, which meant extra investments were made in the neighbourhood. Just when it was expected that things would start improving in the neighbourhood, this was potentially to be endangered by the establishment of an asylum seekers reception center. In response, a ‘neighbourhood sounding board group’ was set up immediately after the announcement of the establishment of the asylum seekers reception center. People from the district were able to express their opinions regularly and were in turn informed of developments surrounding the AZC. A so-called ‘neighbourhood safety group’ was also created, in which the municipality, police and COA listened weekly to possible safety and nuisance complaints from the neighborhood.

On the other hand, the interests of NGOs such as the Dutch Council for Refugees were very different. They had been lobbying for a long time to facilitate more meaningful ways for asylum seekers to spend the waiting time during an asylum procedure. In their opinion this was important in itself, but it was also relevant to help prepare for better integration afterwards. For them Plan Einstein was an opportunity to contribute to these goals and they therefore immediately enthusiastically joined the preparation team from the start. Also Welcome in Utrecht – an NGO that was founded during the ‘refugee crisis’ of 2015–2016 – saw in Plan Einstein a hub from which it was possible to make the lives of asylum seekers less difficult and to bring about more social interaction.

For other groups, again the project meant different things. The local social business community Plan Einstein provided opportunities to guide new businesses and establish links between (social) entrepreneurs and refugees through peer-to-peer coaching by Utrecht entrepreneurs. At the same time it might strengthen their ‘movement’ and represented an opportunity to diversify their local business network. For the knowledge institutes involved, Plan Einstein represented an opportunity to valorise their knowledge, which has recently become an increasingly important objective for universities. The Volksuniversiteit saw an opportunity to spread its knowledge and skills to a new target group: asylum seekers with different levels of English. The Universities of Oxford and Roehampton were interested in finding out how such an initiative might have positive effects, and were therefore motivated to evaluate this project for a number of years.

7 Manoeuvring Multi-level and Multi-sector Collaboration

As we have outlined above, the ‘refugee crisis’ of 2015–2016 opened a window of opportunity for the realization of the local initiative Plan Einstein. In summary, already before the crisis, as we have explained, there were various problems concerning asylum reception that were felt mainly at local level. In addition, a policy vacuum arose at national (and European) level. Due to the ‘refugee crisis’, the theme of asylum reception suddenly also attracted the attention of new parties, such as social entrepreneurs and knowledge institutes that wanted to use their knowledge, skills and network for this theme. Asylum seekers became in some ways ‘the talk of the day’ and because the national government and also the local government were confronted with enormous (time) pressure to host asylum seekers, this theme was high on the agenda, first in the form of emergency relief, but later also in the form of more structural care. This was the case too in Utrecht, where the topic received attention from the green-liberal majority in the city council. And finally, as asylum seekers suddenly became much more important for the ‘urban agenda’, it became possible to apply for a subsidy from a recently established EU fund. In this way the crisis offered opportunities and the moment and opportunity was seized by local officials, in collaboration with the network they had built up.

That the crisis actually offered these opportunities was not accidental. The Plan Einstein alliance was able to acquire support and legitimacy as a result of two developments in the context of broader public governance trends: the increase of multilevel and multisector collaboration (Sorensen and Torfing 2011) and a trend of experimentalist governance (Sabel and Zeitlin 2011). These were the waves on which the initiators could sail and which they could use to credibly embed their arguments and perspectives.

First, with reference to the broad development of multilevel (vertical) cooperation and multisector (horizontal, public-private) networks, the political scientist Benjamin Barber writes in his book ‘If Mayors Ruled the World: Dysfunctional Nations, Rising Cities’ (2013) that such partnerships are becoming increasingly important, because national states alone cannot solve the major transnational problems they face today. According to him, they are too ideologically driven and focused on protecting national interests. This is not a problem when dealing with national policy issues such as housing or education, but the stance is unhelpful in solving transnational challenges such as climate change (see also Bulkeley and Betsill 2005) or refugee issues. Barber states that city governments are better placed to engage with these topics, because they are more pragmatic and inclined to cooperate with other cities and with many different partners, including private parties and international and supranational organizations (such as the EU). In order to make this possible, co-production and co-creation with citizens are becoming more and more generally accepted ways to develop meaningful plans and practices.

In line with these trends, various policy domains have been decentralized to cities in recent years, with cities taking and receiving opportunities for their own interpretations of what to do. In integration policy, cities sometimes choose an interpretation that deviates to a greater or lesser extent from the national policy, and is sometimes in conflict with it (Dekker et al. 2015). This is called ‘decoupling’ of national and local policy, or also the ‘local turn’ in integration policies (Bak Jørgensen 2012; Scholten 2013). Plan Einstein can be interpreted as an example of this broader development, because it is an ‘urban’ project that deviates from the national policy on asylum reception. Plan Einstein was conceived and implemented in a dominantly restrictive national context, which it chose manoeuvre within, not to confront directly, in order to achieve most success. The initiators chose this strategy as the most effective way of making this experiment acceptable. If it would be too confrontational, it might become vetoed. By manoeuvring cautiously the developers created space for the experiment, as we explain below.

The first aspect the initiators manoeuvred was around the national political choice to maintain and strictly manage large scale asylum seekers reception centers. Plan Einstein was created as an ‘add on’ to a regular large scale reception centre in which about 400 asylum seekers were living under the ‘normal’ living conditions in AZCs. The COA agency decided who was able live in the reception centre, for how long and when they would have to move on again. Asylum seekers had to live in similar circumstances as in all other AZCs, which were known to impact their lives negatively: sharing rooms and facilities, having to report weekly, experiencing little privacy, having physical barriers around the premises and security guards at the entrance of the building and having to abide to strict internal regulations etc. So while Plan Einstein intended to enhance the wellbeing of asylum seekers and improve neighbourhood relations by providing opportunities for co-learning and co-living, it had to accept that these goals would be influenced by the conditions asylum seekers had to live in.

The second aspect of the national context Plan Einstein had to manoeuvre were national political sensitivities around the integration of asylum seekers. Aspects that directly fed into integration, such as Dutch language classes are prohibited, in order to more easily facilitate the deportation of asylum seekers after the rejection of their asylum claim. For this reason Plan Einstein developed the ‘future proof’ approach in its education: for example by teaching all course in English. In reality, it transpired that many asylum seekers who lived in the AZC complex of Plan Einstein would receive a residence permit after having gone through the asylum application process, because many of the came from Syria and Eritrea: countries to which hardly anybody would be deported. In this case, asylum seekers might have benefitted too from learning Dutch and preparing for jobs in the Netherlands, as most of them expressed a desire to do.

The third aspect in which Plan Einstein manoeuvered its political context was by designing and implementing a project that would benefit the neighbourhood as well as the asylum seekers. As public opinion was partly welcoming and partly negative towards asylum seekers the initiators of Plan Einstein decided that providing tangible benefits to the neighbourhood (housing for youngsters, free education) might positively impact politics and public opinion on refugees by showing that good relations between asylum seekers and the neighbourhood ‘can be done’.

In this sense, we see Plan Einstein as an example of the local turn, but not to the extent of complete decoupling: the initiators of the project worked within the national political and administrative context instead of against it.

The European funding of the project also helped to bypass local and national objections to the Plan, since with financing available, there was not too much risk involved. As a result, the Ministry of Justice and Security did not stop the urban experiment of Plan Einstein, and in the most recent coalition agreement (2017: 55), the government explicitly created ‘municipal experimental space’ concerning the integration of refugees. Urban experiments provide positive opportunities for testing things out, but they circumvent the danger that the policy must be adopted wholesale immediately. This also helps explain why the implementation agency COA took advantage of this opportunity by enabling collaboration with this experiment, wherein the local AZC organization was closely involved with Plan Einstein, but not one of the partners. The partners of Plan Einstein could therefore exploit the trend of multilevel and multisector collaboration, and were able to present Plan Einstein as an example of this kind of widely supported cooperation processes.

The development of Plan Einstein can also be understood from another perspective, being the trend of experimental governance (Sabel and Zeitlin 2011). In experimentalist governance, it is recognized that top-down blueprint thinking in policy no longer fits in a time when problems have become extremely complex and contexts are highly variable. In the case of unruly policy controversies, such as the climate crisis and the asylum issue, adaptiveness, flexibility and innovation are required (Scholten 2013; Sengers et al. 2016). This is increasingly being organized through multilevel and multi-sector collaboration, so-called collaborative innovation (Sørensen and Torfing 2011) with an ‘innovation orientation’ penetrating throughout the public sector. Plan Einstein is also based on this experimental approach: initially a plan was developed, including the key aspect that, during the course of its implementation, it was expected that choices were adjusted or reconsidered if there was reason to do so. In this sense, it was experiment as learning by doing.

8 Conclusions

Plan Einstein was intended as a way to tackle the problems that had arisen in the existing asylum reception in the Netherlands. The plan tried to find a balance between protecting refugees on the one hand and protecting national economic, socio-cultural and security interests on the other. This concept was developed in the context of a scale mismatch, where management and the debate of the issue was taking place traditionally at national level, but the problems were felt at the local level. There was, as a result something of an impasse. These contexts help explain why the Plan Einstein initiators opted for an urban experiment, which might ultimately also then work to influence national policy. In this experiment, partners from public, private and social sectors worked together (multisector) and they did this simultaneously on multiple levels of government (multilevel).

Above we have explained why it is precisely at this time and in this place that policy entrepreneurs (Kingdon 1984) succeeded in bringing about such an experiment. A number of aspects proved to be crucial in the process. Firstly, it was linking already well-developed alternatives to suddenly emerging problems: local officials had worked together with others for years on developing their ideas about alternative forms of asylum reception. Due to the ‘refugee crisis’, chaos had arisen and in the short term, local emergency relief had to be arranged. Parties were open to all good suggestions in this context and therefore were open also to this proposal. A second crucial aspect was the establishment of public-private partnerships that were an extension of, and built on, existing alliances between the municipal partners and NGOs. This enabled the creation of a partnership in which some of the partners already knew each other, trusted each other and were able to build on earlier methods. At the same time, new partners were brought in who could introduce innovation: new ideas, perspectives, knowledge and skills. The broad objectives of the project made it possible for various partners to emphasize and prioritize different parts of the experiment. Thirdly, the availability of European funding for the project was an important driver and helped to refute financial concerns.

On a theoretical level, we can interpret the creation of local experiments in the recalcitrant policy controversy regarding asylum reception on the basis of concepts of experimental governance and multilevel governance. Urban experiments are part of these larger developments in policy: it is widely accepted that innovation takes place through experiments and that cities and local alliances have a greater role now that it appears that national states are not capable of answering these kinds of issues on their own. However we need to nuance conclusions which would indicate that this is an example of ‘decoupling’ between different levels of integration governance. Constraints in the national context proved to be crucial factors, influencing what the experiment was able to establish. These constraints result in local policy entrepreneurs creating space by manoeuvring within the national context, nibbling at structural constraints: neither openly fighting national government and its agencies, nor ignoring them.

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

Repairing ‘broken narratives’ refers to the ways in which individuals, through telling their stories of traumatic events (including illness or injury) are able to engage in ‘narrative reconstruction’. These concepts are used in narrative research especially in the fields of sociology of health and illness (Hydén and Brockmere 2008).

- 3.

From 2019, replaced in the partnership with University College London, following the Principal Investigator’s move to a different institution.

- 4.

- 5.

- 6.

- 7.

The regional arm of the Dutch Refugee Council, although from this point in the report the national abbreviation of VWN is used as this is how it is referred to colloquially.

- 8.

References

Adviescommissie voor Vreemdelingenzaken. (2013). Verloren tijd: Advies over dagbesteding in de opvang voor vreemdelingen. The Hague: ACVZ.

Bak Jørgensen, M. (2012). The diverging logics of integration policy making at national and city level. International Migration Review, 46(1), 244–278.

Barber, B. (2013). If mayors ruled the world: Dysfunctional nations, rising cities. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Bulkeley, H., & Betsill, M. (2005). Rethinking sustainable cities: Multilevel governance and the ‘urban’ politics of climate change. Environmental Politics, 14(1), 42–63.

Castells, M. (2008). The new public sphere: Global civil society, communication networks, and global governance. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 616(1), 78–93.

Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. (2016). Van opvang naar integratie. www.cbs.nl/-/media/_pdf/2017/25/van%20opvang%20naar%20integratie_incl%20erratum.pdf. Accessed 18 Oct 2018.

Dekker, R., Emilsson, H., Krieger, B., & Scholten, P. (2015). A local dimension of integration policies? A comparative study of Berlin, Malmö, and Rotterdam. International Migration Review, 49(3), 633–658.

Dienst Terugkeer & Vertrek. (2018). Vertrekcijfers. https://www.dienstterugkeerenvertrek.nl/Mediatheek/Vertrekcijfers/index.aspx. Accessed 18 Oct 2018.

Engbersen, G., Dagevos, J., Jennissen, R., Bakker, L., & Leerkens, A. (2015). Geen tijd te verliezen: van opvang naar integratie van asielmigranten (WRR policy brief 4). The Hague: Wetenschappelijke Raad voor het Regeringsbeleid (WRR), Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau (SCP), Wetenschappelijk Onderzoeks- en Documentatie Centrum, Ministerie van Veiligheid & Justitie (WODC).

Geuijen, K. (2004). De asielcontroverse: argumenteren over mensenrechten en nationale belangen. Amsterdam: Dutch University Press.

Geuijen, K., Dekker, R., & Oliver, C. (2017). Lokale oplossingen voor problemen in asielopvang: de ‘vluchtelingencrisis’ als window of opportunity. Tijdschrift over Cultuur & Criminaliteit, 7(3), 74–85.

Hydén, L. C., & Brockmeier, J. (2008). Health, illness & culture: Broken narratives (Routledge studies in health and social welfare, band 2). London: Routledge.

Kingdon, J. W. (1984). Agendas, alternatives and public policies. Boston: Little, Brown and co.

Leerkes, A. S., Boersema, E., van Os, R. M. V., Galloway, A. M., & van Londen, M. (2014). Afgewezen en uit Nederland vertrokken? The Hague: Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek- en Documentatiecentrum.

Lubbers, M., Coenders, M., & Scheeper, P. (2006). Objections to asylum seeker centres: Individual and contextual determinants of resistance to small and large centres in the Netherlands. European Sociological Review, 22(3), 243–257.

NOS. (2016). De AZC inloopavonden, waar ging het mis?https://nos.nl/artikel/2081450-de-azc-inloopavonden-waar-ging-het-mis.html. Accessed 18 Oct 2018.

Oliver, C., Dekker, R., & Geuijen, K. (2018). The Utrecht Refugee Launchpad Evaluation Interim Report. Oxford: University of Roehampton and COMPAS, University of Oxford. Available online at [https://www.compas.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/URLP-interim-report-JULY-2018.pdf]

Rittel, H. W., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155–169.

Sabel, C., & Zeitlin, J. (2011). Experimentalist governance. In D. Levi-Faur (Ed.), Oxford Handbook of Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Scholten, P. W. A. (2013). Agenda dynamics and the multi-level governance of intractable policy controversies: The case of migrant integration policies in the Netherlands. Policy Sciences, 46(3), 217–236.

Sengers, F., Wieczorek, A., & Raven, R. (2016). Experimenting for sustainability transitions: A systematic literature review. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 79(6), 991–998.

Sørensen, E., & Torfing, J. (2011). Enhancing collaborative innovation in the public sector. Administration & Society, 43(8), 842–868.

Swai, S. (2018, January 26). Empty AZCs cost Dutch society 250 million euros. The Holland Times.http://www.hollandtimes.nl/articles/national/empty-azcs-cost-dutch-society-250-million-euros/. Accessed 18 Oct 2018.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Geuijen, K., Oliver, C., Dekker, R. (2020). Local Innovation in the Reception of Asylum Seekers in the Netherlands: Plan Einstein as an Example of Multi-level and Multi-sector Collaboration. In: Glorius, B., Doomernik, J. (eds) Geographies of Asylum in Europe and the Role of European Localities. IMISCOE Research Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25666-1_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25666-1_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-25665-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-25666-1

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)