Abstract

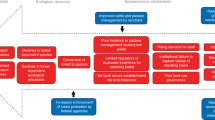

The human health and well-being benefits of contact with nature are becoming increasingly recognised and well understood, yet the implications of nature experiences for biodiversity conservation are far less clear. Theoretically, there are two plausible pathways that could lead to positive conservation outcomes. The first is a direct win-win scenario where biodiverse areas of high conservation value are also disproportionately beneficial to human health and well-being, meaning that the two sets of objectives can be simultaneously and directly achieved, as long as such green spaces are safeguarded appropriately. The second is that experiencing nature can stimulate people’s interest in biodiversity, concern for its fate, and willingness to take action to protect it, therefore generating conservation gains indirectly. To date, the two pathways have rarely been distinguished and scarcely studied. Here we consider how they may potentially operate in practice, while acknowledging that the mechanisms by which biodiversity might underpin human health and well-being benefits are still being determined.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Extinction of experience

- Green space

- Human-wildlife interaction

- Nature connectedness

- Protected areas

- Well-being

-

Green spaces vary in their conservation value, depending on the biodiversity present.

-

Very few are designed and/or managed to deliver synergistic conservation and health benefits.

-

Evidence suggests health might be related to specific, complex natural environments.

-

These green spaces might be of greater conservation value.

-

To maximise health, biodiversity must be in the right places for the right people.

1 Green Spaces Managed Primarily for People

Green spaces may support dramatically different levels of biodiversity, depending on their location, history, purpose and use by people. At one end of the spectrum are the green spaces that have been designed with human health and well-being primarily in mind. Historically, these areas were planned to provide inhabitants with relief from the unsanitary conditions that prevailed in overcrowded industrialised cities (Rayner and Lang 2012) and, while constructed from nature in the form of vegetation, there was no explicit consideration of whether these areas provided valuable habitats for species. Indeed, this anthropocentric view of managing natural resources for the benefit of people has re-emerged over the past two decades, with an emphasis on finding nature-based solutions to issues such as heat mitigation, pollution reduction and storm water protection (e.g. MA 2005; TEEB 2010; European Commission 2011; European Commission Horizon 2020 Expert Group 2015). This is particularly true for urban areas where the majority of the human population across the world live, and improving the health and well-being of these city dwellers is a priority in many national and international policy agendas (European Commission Horizon 2020 Expert Group 2015).

Urban areas are often characterised from a conservation perspective by the negative impacts they have on the ecosystems they replace and abut (e.g. see the discussion in Gaston 2010). Green spaces within cities are often considered too small and isolated from one another to sustain viable species populations (Goddard et al. 2010), requiring a collaborative effort on the part of different stakeholders to redress the lack of connectivity (Davies et al. 2009; Dearborn and Kark 2010). One legacy associated with green spaces intended to deliver aesthetic and recreational benefits is the simplification of habitats as a consequence of frequent management (e.g. mowing, pruning of trees and shrubs, removal of deadwood; Aronson et al. 2017). Likewise, the desire to maximise the multi-functionality of green spaces and infrastructure (e.g. green roofs, sustainable urban drainage systems) has perpetuated this problem further through the planting of horticultural cultivars rather than native species (Haase et al. 2017). While some of these initiatives can support biodiversity (e.g. non-native flowering species can be beneficial for some bees; MacIvor and Ksiazek 2015; Salisbury et al. 2015), the use of horticultural cultivars has been linked to a reduction in the forage value of planting for pollinators in general (Bates et al. 2011; Salisbury et al. 2015). Moreover, the spread of alien invasive species from gardens and parks is another significant issue in many parts of the world (Reichard and White 2001; Russo et al. 2017). The conservation value of green spaces that are popular with people can also be limited by significant levels of disturbance and degradation, which prevent native species from colonising and persisting (Brown and Grant 2005), and result in assemblages dominated by adaptable generalists (Kowarik 2011) and the homogenisation of urban biodiversity (McKinney 2006). Even for human-nature interactions that people perceive as being good for wildlife, such as the supplementary feeding of wild birds, we have little evidence as to whether they deliver biodiversity conservation benefits (Fuller et al. 2008; Robb et al. 2008; Jones 2018).

Despite this, suitable habitat within urban areas can support threatened and specialist species, and warrant conservation attention (Baldock et al. 2015; Ives et al. 2016). In developed regions, where intensive use of the wider landscape, particularly through agriculture, has resulted in species declines, urban areas have become important for sustaining regional abundances of some species. Substantial proportions of the populations of some previously widespread and common species now occur in urban green spaces (e.g. Beebee 1997; Gregory and Baillie 1998; Mason 2000; Bland et al. 2004; Peach et al. 2004; Speak et al. 2015; Ives et al. 2016; Tryjanowski et al. 2017). For instance, over 600 species have been recorded in Weißensee Jewish Cemetery in Berlin. It supports 25 plants, five bats and nine birds that are species of conservation concern, and one of the lichens (Aloxyria ochrocheila) present on the site is considered very rare across the wider region. The cemetery therefore acts as an unintended refuge for a wide range of taxa (Buchholz et al. 2016).

2 Green Spaces Managed Primarily for Biodiversity

At the other end of the green space continuum are formal protected areas, now interpreted as a global conservation network, where the objective is to maintain and enhance biodiversity (see MacKinnon et al. Chap. 16, this volume). Currently, there are more than 200,000 protected areas globally, after a huge expansion of the network over the past few decades (Watson et al. 2014, Butchart et al. 2015). Some of the earliest protected areas were preferentially designated in locations used heavily for recreation (Pressey 1994), and some protected areas are still managed with access and use by people as a primary management goal, such as many of the National Parks in the UK (Smith 2013). However, this is usually the exception rather than the rule for three inter-related reasons.

First, protected areas have overwhelmingly been established in areas not needed for economic activity (Pressey 1994), so they are often sited at higher elevations, on steep slopes, on relatively unfertile soils and far away from cities and productive agricultural land (Pressey et al. 2002; Joppa and Pfaff 2009). Typically, the human population density is low in these areas and, as such, they are shielded from use by people by default. Indeed, the physical distance between human settlements and the location of protected areas can impose a substantial barrier to their recreational use (Kareiva 2008). Protected areas that are close to or within towns and cities tend to be smaller, more fragmented and in poorer ecological condition than those in remote locations (Jones et al. 2018).

Second, there has been a growing emphasis in recent years on proactive conservation strategies, such as those that aim to safeguard the last of the world’s major wilderness areas (Sanderson et al. 2002; Mittermeier et al. 2003; Watson et al. 2017). This is based on the recognition that the predominant threats to biodiversity spread contagiously across landscapes (Boakes et al. 2010), suggesting that if an area can be protected while it is still intact, the risk of eventual habitat clearance or degradation is much lower (Klein et al. 2009). By definition, the absence of a high density of people, and the pressure they bring to bear on landscapes, is a key component of wilderness quality (Venter et al. 2016), thus further building a case for protected area designation in places away from human settlements.

Finally, there is often tension among management agencies about permitting recreation inside protected areas that have been designated for biodiversity conservation, with many viewing the two things as incompatible and preferring that people are actively excluded (Smith 2013). A prime example of this is mountain biking where, arguably, the impact on biodiversity is usually minimal, but is perceived as being much greater by managers and other types of green space user (Hardiman and Burgin 2013). A further complicating factor is that funds for managing protected areas for recreation are often derived from different sources to those centred on biodiversity (Miller et al. 2009). This means that interagency cooperation might be needed to effectively provide facilities for human use, or zoning configurations that minimise recreational pressures (Stigner et al. 2016). This can require substantial investment to deliver and be complex to achieve.

In spite of the historical bias where most protected areas are located away from regions of intense human activity, there is some evidence that new protected areas are now being established in closer proximity to towns and cities. Global biodiversity targets mandate protecting threatened species and landscapes that currently lack formal designation (Butchart et al. 2015), and many of the remaining high conservation value areas occur in fragmented landscapes nearer to human settlements (Brooks et al. 2006; McDonald et al. 2008). For example, recently established Australian protected areas are being preferentially sited in places with high human population density and large numbers of threatened species (Barr et al. 2016). Likewise, 32 cities within the European Union contain Natura 2000 sites (ten Brink et al. 2016).

Some protected areas have successfully integrated human health and well-being objectives into their remit more proactively. For instance, Secovlje Salina Nature Park in Slovenia hosts the Lepa Vida Spa, which has generated jobs and income in both the tourism and health sectors. In turn, this has provided better public access to the park for 50,000 annual visitors, and the habitat quality of the protected area, which is important for supporting migratory birds, has been improved (ten Brink et al. 2016). Similarly, Medvednica Nature Park in Zagreb attracts over a million visitors annually, while also being home to over 20% of Croatia’s entire vascular flora, including more than 90 strictly protected species. Additionally, the park plays a role in improving air quality and mitigating urban air temperatures in neighbouring city suburbs (ten Brink et al. 2016).

3 Moving Forward with Green Spaces Planned for Both People and Biodiversity

Presently, although there are few sites explicitly designed and managed to deliver conservation and human health gains in tandem, the potential for synergistic benefits could be substantial. The opportunities to adopt such a strategy are considerable, given the rapid rates of urbanisation globally and that many regions are yet to be developed (Nilon et al. 2017). Urbanisation will not be geographically homogenous, chiefly taking place in small cities comprising less than 500,000 inhabitants across the Global South (United Nations 2015). This vast conversion of land to built infrastructure will undoubtedly pose a threat to biodiversity, not least because most of it will occur in extremely biodiverse regions such as the Brazilian Atlantic Forest and Guinean Forests of West Africa (Seto et al. 2012). Formal conservation protection is therefore imperative to prevent extinctions (Cincotta et al. 2000; Brooks et al. 2006; Venter et al. 2014). Justifying the need to protect natural environments in and around where people live to deliver a multi-faceted suite of objectives is more likely to be persuasive to decision-makers than a rationale based solely on conservation. In already established towns and cities, green spaces can be ‘retrofitted’ to provide complementary conservation and human health gains (for further information, see Hunter et al. Chap. 17, and Heiland et al. Chap. 19, both this volume). For example, initiatives such as the Biophilic Cities network (http://biophiliccities.org/) promote biodiversity as a central tenet of urban planning and management, so that improvements in human health and well-being arise from co-existence (Beatley and van den Bosch 2018). Metrics related to levels of biodiversity, wildness, tree cover and green space accessibility are included as indicators against which the performance of individual cities can be gauged.

Although not studied extensively thus far, there is evidence to suggest that positive human health and well-being outcomes might be related to specific and often complex natural environments, which could be of conservation value. For instance, people enjoy forests because of their quiet atmosphere, scenery and fresh air, which helps with stress management and relaxation (Li and Bell 2018). In Zurich, Sihlwald Forest is a major recreation area for the city. Formerly a timber concession, the ecosystem is now left to function with minimal human intervention and, therefore, offers residents a different sort of nature experience to more manicured green spaces (Seeland et al. 2002; Konijnendijk 2008).

The decisions regarding where green spaces should be located and how they are managed are complex, with conservation value being one of many factors that must be taken into consideration. Inevitably, biodiversity will be traded off against other economic and societal goals (Nilon et al. 2017). However, maximising the size of green spaces planned for both people and biodiversity is likely to be important for their success. While it is widely accepted that larger areas are likely to sustain more species (Beninde et al. 2015), evidence is growing to suggest that the same might be true for the supply of human health and well-being benefits. For instance, larger forested areas are preferred for outdoor activities (Tyrväinen et al. 2007).

Another core challenge associated with maximising the human health outcomes derived from experiencing nature is making sure that biodiversity is in the right locations for the right people. This is critical because the likelihood of someone visiting a site drops dramatically with distance, with only the fraction of the population that is already strongly connected to nature willing to travel to experience it (Shanahan et al. 2015). Indeed, cities are often characterised by a wide array of inequalities, with those living in deprived communities having the most to gain from using nearby green spaces (Mitchell and Popham 2008; Kabisch Chap. 5, this volume; Cook et al. Chap. 11, this volume). If the health and well-being of all urban residents were prioritised, then one would expect publicly owned green spaces to be more or less evenly distributed across the spatial extent of towns and cities (Boone et al. 2009; Landry and Chakroborty 2009; Pham et al. 2012). On the other hand, if green spaces were being used actively as an intervention to promote better human health and well-being, their placement would mostly likely be adjacent to communities characterised by a high prevalence of health disorders, such as depression and obesity (Lin et al. 2014). However, either is rarely the case, as individuals from ethnic/racial minorities (Heynen et al. 2006; Landry and Chakroborty 2009; Wolch et al. 2013) and/or lower socio-economic status (Vaughan et al. 2013) have comparatively worse access to high-quality green space than the rest of the population. It is therefore vital to ensure that the health benefits that might be derived from conservation initiatives are not just confined to societal groups that have the financial and/or social means to access them (Wolch et al. 2014).

4 Experiencing Nature to Promote Conservation

It is commonly asserted that urbanisation has led to the human population becoming progressively disconnected from the natural world (Wilson 1984; Pyle 2003; Miller 2005), a phenomenon that has variously been referred to as the ‘extinction of experience’ (Miller 2005), ‘nature deficit disorder’ (Louv 2008) and ‘ecological boredom’ (Monbiot 2013). By exposing people to nature, it is thought that these experiences can enhance an individual’s connection with nature and, in turn, promote conservation concern and pro-environmental behaviours (see Soga and Gaston 2016; De Young Chap. 13, this volume). For instance, Rogerson et al. (2017) found relationships between people experiencing nature and positive environmental behaviour, such as volunteering with conservation organisations. Likewise, childhood experiences of nature have been linked to connectedness to nature in a study of French adults (Colléony et al. 2017), and individuals who grew up in rural areas demonstrated a greater preference for gardens containing more flowers and woodland species than urbanities (Shwartz et al. 2013). Nonetheless, the evidence underlying the relationship between nature experience and positive attitudes/behaviours remains scant and is yet to be fully established (Soga and Gaston 2016).

Individuals may not need to experience biodiversity to want to conserve it (termed ‘existence value’) (Cooper et al. 2016). This has been shown for coastal ecosystems on Vancouver Island, Canada (Klain and Chan 2012) and marine protected areas in the UK (Kenter et al. 2016), and can be a potential mediator between nature connectedness and well-being (Cleary et al. 2017). Additionally, it is difficult to draw meaningful lessons from studies due to the level of inconsistency between the definitions of what constitutes an experience, what comprises nature, and what attitude or perception is being measured (Clayton et al. 2017; Ives et al. 2017). Moreover, the ‘extinction of experience’ concept is considered oversimplified because it fails to acknowledge the multi-dimensionality of people’s experiences of biodiversity (Clayton et al. 2017), and that some interactions with species can be negative, frightening or uncomfortable (Bixler and Floyd 1997). Relationships with nature are likely to be highly specific to individuals, with cultural contexts and norms also being important and variable across societies (Voigt and Wurster 2014). For example, feeding wild birds is a very popular human-biodiversity interaction in both the UK and the USA (Freyfogle 2003; Defra 2011), but negative associations with birds in Europe may inhibit a connectedness to nature for some individuals (Ratcliffe et al. 2013). Similarly, a fear of birds (known as ‘ornithophobia’) in Honduras has been reported to occur where birds are perceived as either pest species or as negative spiritual symbols (Bonta 2008). This is a fundamental consideration when designing and maintaining green spaces, as synergistic human health and conservation benefits will not be delivered successfully if the residents are intolerant of the biodiversity they support.

5 Conclusion

While very few green spaces are implemented explicitly with both conservation and human health and well-being in mind, the potential for delivering win-win outcomes is considerable. This is particularly apposite, given the rate and distribution of future urbanisation predicted across the highly biodiverse regions of the Global South. However, the rapidly growing body of research examining nature-related health benefits has yet to tease apart the relative value of green spaces that support different levels of biodiversity and ecosystem complexity. This knowledge gap needs to be addressed, so a strong evidence-base is in place to inform effective policy and practice.

References

Aronson MF, Lepczyk CA, Evans KL, Goddard MA, Lerman SB, MacIvor JS, Nilon CH, Vargo T (2017) Biodiversity in the city: key challenges for urban green space management. Front Ecol Environ 15:1–8

Baldock KCR, Goddard MA, Hicks DM, Kunin WE, Mitschunas N, Osgathorpe LM, Potts SG, Robertson KM, Scott AV, Stone GN, Vaughan IP, Memmott J (2015) Where is the UK’s pollinator biodiversity? The importance of urban areas for flower-visiting insects. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 282:20142849

Barr LM, Watson JEM, Possingham HP, Iwamura T, Fuller RA (2016) Progress in improving the protection of species and habitats in Australia. Biol Conserv 200:184–191

Bates AJ, Sadler JP, Fairbrass AJ, Falk SJ, Hale JD, Matthews TJ (2011) Changing bee and hoverfly pollinator assemblages along an urban-rural gradient. PLoS One 6:e23459

Beatley T, van den Bosch KC (2018) Urban landscapes and public health. In: van den Bosch M, Bird W (eds) Nature and Public Health. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Beebee TJC (1997) Changes in dewpond numbers and amphibian diversity over 20 years on chalk downland in Sussex, England. Biol Conserv 81:215–219

Beninde J, Veith M, Hochkirch A (2015) Biodiversity in cities needs space: a meta-analysis of factors determining intra-urban biodiversity variation. Ecol Lett 18:581–592

Bixler RD, Floyd MF (1997) Nature is scary, disgusting, and uncomfortable. Environ Behav 29:443–467

Bland RL, Tully J, Greenwood JJD (2004) Birds breeding in British gardens: an underestimated population? Bird Study 51:96–106

Boakes EH, Mace GM, McGowan PJK, Fuller RA (2010) Extreme contagion in global habitat clearance. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 277:1081–1085

Bonta M (2008) Valorizing the relationships between people and birds: experiences and lessons from Honduras. Ornitol Neotropical 19:595–604

Boone GC, Buckley GL, Grove MJ, Sister C (2009) Parks and people: an environmental justice inquiry in Baltimore, Maryland. Assoc Am Geogr 99:767–787

Brooks TM, Mittermeier RA, da Fonseca GAB, Gerlach J, Hoffmann M, Lamoreux JF, Mittermeier CG, Pilgrim JD, Rodrigues ASL (2006) Global biodiversity conservation priorities. Science 313:58–61

Brown C, Grant M (2005) Biodiversity and human health: what role for nature in healthy urban planning? Built Environ 31:326–338

Buchholz S, Blick T, Hannig K, Kowarik I, Lemke A, Otte V, Scharon J, Schonhofer A, Teige T, von der Lippe M, Seitz B (2016) Biological richness of a large urban cemetery in Berlin: results of a multi-taxon approach. Biodivers Data J 4:e7057

Butchart SHM, Clarke M, Smith RJ, Sykes RE, Scharlemann JPW, Harfoot M, Buchanan GM, Angulo A, Balmford A, Bertzky B, Brooks TM, Carpenter KE, Comeros-Raynal MT, Cornell J, Francesco Ficetola G, Fishpool LDC, Fuller RA, Geldmann J, Harwell H, Hilton-Taylor C, Hoffmann M, Joolia A, Joppa L, Kingston N, May I, Milam A, Polidoro B, Ralph G, Richman N, Rondinini C, Segan D, Skolnik B, Spalding M, Stuart SN, Symes A, Taylor J, Visconti P, Watson J, Wood L, Burgess ND (2015) Shortfalls and solutions for meeting national and global conservation area targets. Conserv Lett 8:329–337

Cincotta RP, Wisnewski J, Engelman R (2000) Human population in the biodiversity hotspots. Nature 404:990–992

Clayton S, Coll A, Conversy P, Maclouf E, Martin L, Torres A, Truong M, Prevot A (2017) Transformation of experience: toward a new relationship with nature. Conserv Lett 10:645–651

Cleary A, Fielding KS, Bell SL, Murray Z, Roiko A (2017) Exploring potential mechanisms involved in the relationship between eudaimonic wellbeing and nature connection. Landsc Urban Plan 158:119–128

Colléony A, Prévot A-C, Saint Jalme M, Clayton S (2017) What kind of landscape management can counteract the extinction of experience? Landsc Urban Plan 159:23–31

Cooper N, Brady E, Steen H, Bryce R (2016) Aesthetic and spiritual values of ecosystems: recognising the ontological and axiological plurality of cultural ecosystem ‘services’. Ecosyst Serv 21:218–229

Dallimer M, Irvine KN, Skinner AMJ, Davies ZG, Rouquette JR, Maltby LL, Warren PH, Armsworth PR, Gaston KJ (2012) Biodiversity and the feel-good factor: understanding associations between self-reported human well-being and species richness. Bioscience 62:47–55

Davies ZG, Fuller RA, Loram A, Irvine KN, Sims V, Gaston KJ (2009) A national scale inventory of resource provision for biodiversity within domestic gardens. Biol Conserv 142:761–771

Dearborn DC, Kark S (2010) Motivations for conserving urban biodiversity. Conserv Biol 24:432–440

Defra (2011) A biodiversity strategy for England. Measuring progress: 2010 assessment. Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, London

European Commission (2011) Our life insurance, our natural capital: an EU biodiversity strategy to 2020. European Commission, Brussels

European Commission Horizon 2020 Expert Group (2015) Towards an EU research and innovation policy agenda for nature-based solutions and re-naturing cities. A report for the European Commission. European Commission, Brussels

Freyfogle ET (2003) Conservation and the culture war. Conserv Biol 17:354–355

Fuller RA, Irvine KN, Devine-Wright P, Warren PH, Gaston KJ (2007) Psychological benefits of greenspace increase with biodiversity. Biol Lett 3:390–394

Fuller RA, Warren PH, Armsworth PR, Barbosa O, Gaston KJ (2008) Garden bird feeding predicts the structure of urban avian assemblages. Divers Distrib 14:131–137

Gaston KJ (2010) Urban ecology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Goddard MA, Dougill AJ, Benton TG (2010) Scaling up from gardens: biodiversity conservation in urban environments. Trends Ecol Evol 25:90–98

Gregory RD, Baillie SR (1998) Large-scale habitat use of some declining British birds. J Appl Ecol 35:785–799

Haase D, Kabisch S, Haase A, Andersson E, Banzhaf E, Baró F, Brenck M, Fischer LK, Frantzeskaki N, Kabisch N, Krellenberg K (2017) Greening cities – To be socially inclusive? About the alleged paradox of society and ecology in cities. Habitat Int 64:41–48

Hardiman N, Burgin S (2013) Mountain biking: downhill for the environment or chance to up a gear? Int J Environ Stud 70:976–986

Heynen N, Perkins HA, Roy P (2006) The political ecology of uneven urban green space. The impact of political economy on race and ethnicity in producing environmental inequality in Milwaukee. Urban Aff Rev 42:3–25

Ives CD, Lentini PE, Threlfall CG, Ikin K, Shanahan DF, Garrard GE, Bekessy SA, Fuller RA, Mumaw L, Rayner L, Rowe R, Valentine LE, Kendal D (2016) Cities are hotspots for threatened species. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 25:117–126

Ives CD, Giusti M, Fischer J, Abson DJ, Klaniecki K, Dorninger C, Laudan J, Barthel S, Abernethy P, Martín-López B, Raymond CM, Kendal D, von Wahrden H (2017) Human–nature connection: a multidisciplinary review. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 26–27:106–113

Jones D (2018) The birds at my table: why we feed wild birds and why it matters. Cornell University Press, Ithaca

Jones KR, Venter O, Fuller RA, Allan JR, Maxwell SL, Negret PJ, Watson JEM (2018) One-third of global protected land is under intense human pressure. Science 360:788–791

Joppa LN, Pfaff A (2009) High and far: biases in the location of protected areas. PLoS One 4:e8273

Kareiva P (2008) Ominous trends in nature recreation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:2757–2758

Kenter JO, Jobstvogt N, Watson V, Irvine KN, Christie M, Bryce R (2016) The impact of information, value-deliberation and group-based decision-making on values for ecosystem services: integrating deliberative monetary valuation and storytelling. Ecosyst Serv 21:270–290

Klain S, Chan K (2012) Navigating coastal values: participatory mapping of ecosystem services for spatial planning. Ecol Econ 82:104–113

Klein CJ, Wilson KA, Watts M, Stein J, Carwardine J, Mackey B, Possingham HP (2009) Spatial conservation prioritization inclusive of wilderness quality: a case study of Australia’s biodiversity. Biol Conserv 142:1282–1290

Konijnendijk CC (2008) The forest and the city – The cultural landscape of urban woodland. Springer, Berlin

Kowarik I (2011) Novel urban ecosystems, biodiversity, and conservation. Environ Pollut 159:1974–1983

Landry SM, Chakraborty J (2009) Street trees and equity: evaluating the spatial distribution of an urban amenity. Environ Plan A 41:2651–2670

Li Q, Bell S (2018) The great outdoors: forests, wilderness and public health. In: van den Bosch M, Bird W (eds) Nature and public health. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Lin BB, Fuller RA, Bush R, Gaston KJ, Shanahan DF (2014) Opportunity or orientation? Who uses urban parks and why. PLoS One 9:e87422

Louv R (2008) Last child in the woods: saving our children from nature-deficit disorder. Atlantic Books, London

MA (2005) Millennium ecosystem assessment – ecosystems and human well-being. Island Press, Washington DC

MacIvor S, Ksiazek K (2015) Invertebrates on green roofs. In: Sutton R (ed) Green roof ecosystems. Springer, Cham

Mason CF (2000) Thrushes now largely restricted to the built environment in eastern England. Divers Distrib 6:189–194

McDonald RI, Kareiva P, Formana RTT (2008) The implications of current and future urbanization for global protected areas and biodiversity conservation. Biol Conserv 141:1695–1703

McKinney ML (2006) Urbanization as a major cause of biotic homogenization. Biol Conserv 127:247–260

Miller JR (2005) Biodiversity conservation and the extinction of experience. Trends Ecol Evol 20:430–434

Miller JR, Groom M, Hess GR, Steelman T, Stokes DL, Thompson J, Bowman T, Fricke L, King B, Marquardt R (2009) Biodiversity conservation in local planning. Conserv Biol 23:53–63

Mills JG, Weinstein P, Gellie NJC, Weyrich LS, Lowe AJ, Breed MF (2017) Urban habitat restoration provides a human health benefit through microbiome rewilding: the Microbiome rewilding hypothesis. Restor Ecol 25:866–872

Mitchell R, Popham F (2008) Effect of exposure to natural environment on health inequalities: an observational population study. Lancet 372:1655–1660

Mittermeier RA, Mittermeier CG, Brooks TM, Pilgrim JD, Konstant WR, da Fonseca GAB, Kormos C (2003) Wilderness and biodiversity conservation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:10309–10313

Monbiot G (2013) Feral: searching for enchantment on the frontiers of rewilding. Allen Lane, Penguin Press, London

Nilon CH, Aronson MFJ, Cilliers SS, Dobbs C, Frazee LJ, Goddard MA, O’Neill KM, Roberts D, Stander EK, Werner P, Winter M, Yocom KP (2017) Planning for the future of urban biodiversity: a global review of city-scale initiatives. Bioscience 67:332–342

Peach WJ, Denny M, Cotton PA, Hill IF, Gruar D, Barritt D, Impet A, Mallord J (2004) Habitat selection by song thrushes in stable and declining farmland populations. J Appl Ecol 41:275–293

Pett TJ, Shwartz A, Irvine KN, Dallimer M, Davies ZG (2016) Unpacking the people–biodiversity paradox: a conceptual framework. Bioscience 66:576–583

Pham TTH, Apparicio P, Séguin AM, Landry S, Gagnon M (2012) Spatial distribution of vegetation in Montreal: an uneven distribution or environmental inequity? Landsc Urban Plan 107:214–224

Pressey RL (1994) Ad hoc reservations: forward or backward steps in developing representative reserve systems? Conserv Biol 8:662–668

Pressey RL, Whish GL, Barrett TW, Watts ME (2002) Effectiveness of protected areas in north-eastern New South Wales: recent trends in six measures. Biol Conserv 106:57–69

Pyle RM (2003) Nature matrix: reconnecting people and nature. Oryx 37:206–214

Ratcliffe E, Gatersleben P, Sowden PT (2013) Bird sounds and their contributions to perceived attention restoration and stress recovery. J Environ Psychol 36:221–228

Rayner G, Lang T (2012) Ecological public health: reshaping the conditions for good health. Routledge, Abingdon

Reichard SH, White P (2001) Horticulture as pathways of plant introductions in the United States. Bioscience 51:103–113

Robb GN, McDonald RA, Chamberlain DE, Bearhop S (2008) Food for thought: supplementary feeding as a driver of ecological change in avian populations. Front Ecol Environ 6:476–484

Rogerson M, Barton J, Bragg R, Pretty J (2017) The health and wellbeing impacts of volunteering with the wildlife trusts. University of Essex, Colchester

Russo A, Escobedo FJ, Cirella GT, Zerbe S (2017) Edible green infrastructure: an approach and review of provisioning ecosystem services and disservices in urban environments. Agric Ecosyst Environ 242:53–66

Salisbury A, Armitage J, Bostock H, Perry J, Tatchell M, Thompson K (2015) Enhancing gardens as habitats for flower-visiting aerial insects (pollinators): should we plant native or exotic species? J Appl Ecol 52:1156–1164

Sanderson EW, Jaiteh M, Levy MA, Redford KH, Wannebo AV, Woolmer G (2002) The human footprint and the last of the wild. Bioscience 52:891–904

Schwarz N, Moretti M, Bugalho MN, Davies ZG, Haase D, Hack J, Hof A, Melero Y, Pett TJ, Knapp S (2017) Understanding biodiversity-ecosystem service relationships in urban areas: a comprehensive literature review. Ecosyst Serv 27:161–171

Seeland K, Moser K, Scheutle H, Kaiser FG (2002) Public acceptance of restrictions imposed on recreational activities in the per-urban Sihlwald Nature Reserve, Sihlwald, Switzerland. Urban For Urban Green 1:49–57

Seto KC, Güneralp B, Hutyra LR (2012) Global forecasts of urban expansion to 2030 and direct impacts on biodiversity and carbon pools. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:16083–16088

Shanahan DF, Lin BB, Gaston KJ, Bush R, Fuller RA (2015) What is the role of trees and remnant vegetation in attracting people to urban parks? Landsc Ecol 30:153–165

Shwartz A, Cheval H, Simon L, Julliard R (2013) Virtual garden computer program for use in exploring the elements of biodiversity people want in cities. Conserv Biol 27:876–886

Smith J (2013) Protected areas: Origins, criticisms and contemporary issues for outdoor recreation. Centre for environment and society research. Working paper series no. 15. Birmingham City University, Birmingham

Soga M, Gaston KJ (2016) Extinction of experience: the loss of human-nature interactions. Front Ecol Environ 14:94–101

Speak AF, Mizgajski A, Borysiak J (2015) Allotment gardens and parks: provision of ecosystem services with an emphasis on biodiversity. Urban For Urban Green 14:772–781

Stigner MG, Beyer HL, Klein CJ, Fuller RA (2016) Reconciling recreational use and conservation values in a coastal protected area. J Appl Ecol 53:1206–1214

TEEB (2010) The economics of ecosystems and biodiversity: mainstreaming the economics of nature: a synthesis of the approach, conclusions and recommendations of TEEB. Progress Press, Malta

ten Brink P, Mutafoglu K, Schweitzer J-P, Kettunen M, Twigger-Ross C, Baker J, Kuipers Y, Emonts M, Tyrväinen L, Hujala T & Ojala A (2016) The Health and Social Benefits of Nature and Biodiversity Protection. A report for the European Commission. Institute for European Environmental Policy, London/Brussels

Tryjanowski P, Morelli F, Mikula P, Krištín A, Indykiewicz P, Grzywaczewski G, Kronenberg J, Jerzak L (2017) Bird diversity in urban green space: a large-scale analysis of differences between parks and cemeteries in Central Europe. Urban For Urban Green 27:264–271

Tyrväinen L, Mäkinen K, Schipperijn J (2007) Tools for mapping social values of urban woodlands and other green areas. Landsc Urban Plan 79:5–19

United Nations (2015) World urbanization prospects, the 2014 revision. United Nations, New York

Vaughan KB, Kaczynski AT, Wilhelm Stanis SA, Besenyi GM, Bergstrom R, Heinrich KM (2013) Exploring the distribution of park availability, features, and quality across Kansas City, Missouri by income and race/ethnicity: an environmental justice investigation. Ann Behav Med 45:S28–S38

Venter O, Fuller RA, Segan DB, Carwardine J, Brooks T, Butchart SHM, Di Marco M, Iwamura T, Joseph L, O’Grady D, Possingham HP, Rondinini C, Smith RJ, Venter M, Watson JEM (2014) Targeting global protected area expansion for imperiled biodiversity. PLoS Biol 12:e101891

Venter O, Sanderson EW, Magrach A, Allan JR, Beher J, Jones KR, Possingham HP, Laurance WF, Wood P, Fekete PM, Levy MA, Watson JEM (2016) Sixteen years of change in the global terrestrial human footprint and implications for biodiversity conservation. Nat Commun 7:12558

Voigt A, Wurster D (2014) Does diversity matter? The experience of urban nature’s diversity: case study and cultural concept. Ecosyst Serv 12:200–208

Watson JEM, Dudley N, Segan DB, Hockings M (2014) The performance and potential of protected areas. Nature 515:67–73

Watson JEM, Shanahan DF, Di Marco M, Allan J, Laurance WF, Sanderson EW, Mackey B, Venter O (2017) Catastrophic declines in wilderness areas undermine global environment targets. Curr Biol 26:2929–2934

Wilson EO (1984) Biophilia. Harvard University Press, Massachusetts

Wolch JR, Wilson JP, Fehrenbach J (2013) Parks and park funding in Los Angeles: an equity-mapping analysis. Urban Geogr 26:4–35

Wolch JR, Byrne J, Newell JP (2014) Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: the challenge of making cities ‘just green enough’. Landsc Urban Plan 125:234–244

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to our respective funders: ZGD is supported by the European Research Council (ERC) Consolidator Grant 726104; MD is supported by the UK Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) grant NE/R002681/1; JCF is supported by the UK Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) scholarship ES/J500148/1; and, RAF is supported by an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Davies, Z.G., Dallimer, M., Fisher, J.C., Fuller, R.A. (2019). Biodiversity and Health: Implications for Conservation. In: Marselle, M., Stadler, J., Korn, H., Irvine, K., Bonn, A. (eds) Biodiversity and Health in the Face of Climate Change. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02318-8_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02318-8_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-02317-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-02318-8

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)