Abstract

In everyday social interactions, people’s facial expressions sometimes reflect genuine emotion (e.g., anger in response to a misbehaving child) and sometimes do not (e.g., smiling for a school photo). There is increasing theoretical interest in this distinction, but little is known about perceived emotion genuineness for existing facial expression databases. We present a new method for rating perceived genuineness using a neutral-midpoint scale (–7 = completely fake; 0 = don’t know; +7 = completely genuine) that, unlike previous methods, provides data on both relative and absolute perceptions. Normative ratings from typically developing adults for five emotions (anger, disgust, fear, sadness, and happiness) provide three key contributions. First, the widely used Pictures of Facial Affect (PoFA; i.e., “the Ekman faces”) and the Radboud Faces Database (RaFD) are typically perceived as not showing genuine emotion. Also, in the only published set for which the actual emotional states of the displayers are known (via self-report; the McLellan faces), percepts of emotion genuineness often do not match actual emotion genuineness. Second, we provide genuine/fake norms for 558 faces from several sources (PoFA, RaFD, KDEF, Gur, FacePlace, McLellan, News media), including a list of 143 stimuli that are event-elicited (rather than posed) and, congruently, perceived as reflecting genuine emotion. Third, using the norms we develop sets of perceived-as-genuine (from event-elicited sources) and perceived-as-fake (from posed sources) stimuli, matched on sex, viewpoint, eye-gaze direction, and rated intensity. We also outline the many types of research questions that these norms and stimulus sets could be used to answer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Facial expressions often reflect genuine emotion, elicited by real, remembered or imagined events (i.e., “event-elicited”). For example, someone might display a fearful expression because they are genuinely afraid of a spider, or a sad expression when bringing to mind the loss of a loved one. On other occasions, we observe people posing expressions in the absence of a congruent underlying emotion. A person may, for example, put on a smile for a family portrait but not experience any strong emotion, or a parent may pose a sad face as part of a playful game with their child. Increasingly, researchers have become interested in this distinction between event-elicited and posed expressions, and whether observers perceive the expressions as showing genuine emotion or not (i.e., perceive them as “fake”). Although the focus has mostly been on happy expressions (Ekman & Friesen, 1982; Frank, Ekman, & Friesen, 1993; for a review, see Gunnery & Ruben, 2016), more recent work has begun to include a broader range of emotions, asking questions such as: Can adults discriminate genuineness in facial expressions other than happiness (e.g., sadness, fear, disgust; Douglas, Porter, & Johnston, 2012; McLellan, Johnston, Dalrymple-Alford, & Porter, 2010)? Can children do the same (sadness, fear; Dawel, Palermo, O’Kearney, & McKone, 2015)? Is the ability to perceive genuineness affected by clinical disorders such as depression or traumatic brain injury (sadness, happiness; Douglas et al., 2012; McLellan & McKinley, 2013), or associated with individual differences variables such as empathy (Dawel, Palermo, O’Kearney, & McKone, 2015)? And does neural activation differ for event-elicited versus posed expressions (sadness, happiness; McLellan, Wilcke, Johnston, Watts, & Miles, 2012)?

To date, the key independent variables in this type of research have tended to be stimulus elicitation method (e.g., posed vs. event-elicited), the self-reported emotion of the person displaying the expression (i.e., whether the displayer reported feeling the emotion or not), or the presence/absence of particular physical characteristics that are supposed to correspond with genuine emotion (e.g., “Duchenne” crinkles around the eye present for genuine happy but not fake happy; Ekman & Friesen, 1982). However, another set of important questions relates to how percepts of emotion genuineness might drive observers’ responses. Given that human observers have no direct access to other people’s emotions, it is likely to be their perception of people’s emotional expressions that drives responses in many circumstances. For example, a parent’s response to their child displaying a sad expression could differ depending on whether the parent perceives the expression as reflecting genuine sadness (in which case the parent might feel empathy) or fake sadness (in which case the parent might feel annoyed). Crucially, the parent’s response results from their perception of the expression, irrespective of what the child actually felt or exactly what their expression looked like physically. Currently, there are very few data regarding perceived emotion genuineness for existing facial expression databases, and no stimulus set is available in which the expressions have been established as being perceived as genuine (or fake, for that matter), across a broad range of emotions.

Study aims: development of norms and new stimulus sets

The purpose of the present study is to redress this gap in knowledge, starting by using a neutral-midpoint scale to rate perceived genuineness for the first time. We use this rating method to obtain normative values of perceived genuineness for a range of stimuli from different sources, displaying angry, disgusted, fearful, sad, and happy facial expressions. These expressions were selected because they are of particular interest to certain longstanding research topics (e.g., anger and fear in anxiety: Fox, Mathews, Calder, & Yiend, 2007; fear and sadness in psychopathy: Blair, 2006; Dawel, O’Kearney, McKone, & Palermo, 2012; disgust in Parkinson’s disease: Suzuki, Hoshino, Shigemasu, & Kawamura, 2006; happiness in bipolar disorder: Gruber, 2011; fear and disgust in brain injury studies, due to associations with the amygdala and insula respectively: Adolphs, 2002).

Our study makes three primary contributions. First, we establish norms for many of the stimuli from two popular databases that are widely used in the literature, the Pictures of Facial Affect (PoFA; Ekman & Friesen, 1976) and the Radboud Faces Database (RaFD; Langner et al., 2010), and for the only published set (the McLellan faces; as provided to us, T. McLellan, personal communication, November 24, 2010; see also McLellan et al., 2010) where the actual emotional state of the displayer has been verified (by self-report) for emotions other than happiness.

Second, we present norms for a much larger number of stimuli from additional sources that were selected for their potential to be either perceived as genuine or perceived as fake because they were derived, respectively, from event-elicited or posed databases. These norms allow us to provide researchers with a list of 143 stimuli that are perceived as reflecting genuine emotion from event-elicited sources for which the displayer is likely to actually be feeling the emotion, giving congruency between actual and perceived emotion. The types of questions for which these stimuli would be suitable are ones in which researchers are interested in the processing of others’ emotions (as apparent through their facial expressions), rather than simply the ability to perceptually code a facial configuration as belonging to a particular emotion category (e.g., labeling the expression as anger, disgust, fear, etc.).

Third, we use the norms to develop two new matched stimulus sets: one perceived as genuine, from event-elicited sources, and the other perceived as fake, from posed sources. Both sets again have congruency between likely actual emotion and perceived emotion, and also have good labeling accuracy and matching on sex, viewpoint, eye-gaze direction, and rated intensity. These stimuli are suitable for researchers interested in questions where a key independent variable is observers’ perceptions of emotion genuineness, such as: Do children perceive genuineness in the same way as adults, and does this vary by expression category? Do perceptions of genuineness differ in special populations (e.g., people with amygdala damage) as compared to typically developing adults (our norms), and if so, does this result in problematic social behavior (e.g., co-operating with someone who is faking a smile)? Or, does the extent to which an expression is perceived or not perceived as genuine influence observers’ social evaluations (e.g., approachability, trustworthiness)?

Application of a neutral-midpoint scale to rate perceived emotion genuineness

Our first concern was how to best measure perceived emotion genuineness. Only a few studies have collected ratings of perceived genuinenessFootnote 1 for popular facial expression stimuli (e.g., we are aware of no such data for the PoFA; Ekman & Friesen, 1976). Where studies have collected ratings, their methods have not provided the type of data needed to establish in any absolute sense whether the stimuli are perceived as genuine versus fake (e.g., Krumhuber & Manstead, 2009; Langner et al., 2010; Thibault, Gosselin, Brunel, & Hess, 2009). This limitation arises because scales have not included a clear “neutral” point, so that observers can indicate where their perception switches from genuine to fake. For example, Langner et al. (2010, p. 6) obtained ratings of perceived genuineness for the RaFD stimulus set using the scale, “rate the emotional expression of the shown face with regard to the genuineness,” where +1 = faked and +5 = genuine. The mean rating across the set was around 3. However, there was no neutral point against which to interpret this number. That is, we do not know whether participants treated 3 (the scale midpoint) as the “neutral” value, with ratings of 1 and 2 meaning the expressions are perceived as faked, and ratings of 4 and 5 meaning they are perceived as genuine; or, alternatively, whether participants used 1 for faked emotion, and any numbers from 2 upward to indicate genuineness (of varying degrees). The first interpretation would imply that the RaFD faces were generally not perceived as showing genuine emotion (except for happiness, which was rated higher than other expressions at M = 3.8/5), whereas the second interpretation would imply that all of the expressions looked genuine. Overall, these types of rating scales provide high-quality data about the relative perceived genuineness of stimuli (e.g., so that they can be rank-ordered from most to least genuine), but do not allow us to determine whether a stimulus is perceived as genuine versus fake in any absolute sense.

The other approach used in the previous literature has been to have people simply make a decision as to whether or not an expression is genuine. Such tasks include asking, “Are the following people feeling happiness?” with a yes/no response (McLellan et al., 2010), and “Is this person really happy or just pretending to be happy?” (Del Giudice & Colle, 2007). This approach has the opposite limitation from the previous one. Specifically, it provides data about the absolute perception as genuine or fake. However, it provides far less information about the relative perceived genuineness of different stimuli than does a rating scale.

To address the limitations of previous methods, we introduce a neutral-midpoint scale to rate perceived genuineness (Fig. 1a) of the type that has been successfully used to rate other face attributes that are naturally bidirectional (e.g., approach/avoid; Willis, Palermo & Burke, 2011). Our scale runs from –7 = completely fake to +7 = completely genuine, and, crucially, includes a neutral midpoint at 0, which is labeled don’t know. Thus, ratings above 0 indicate that stimuli are perceived as showing genuine emotion, and those below 0 indicate that stimuli are perceived as fake. This method allows us to compare a given stimulus to 0 to determine whether it is perceived as genuine versus fake in absolute terms, and at the same time provides detailed information regarding where that stimulus lies relative to others of the same type (e.g., +7 indicates that the emotional expression is perceived as more clearly genuine than +4, which in turn is more clearly genuine than +1).

Tasks used in the present study. (a) Our new neutral-midpoint scale for rating perceived genuineness (see the Method section for the full instructions given to participants regarding the meanings of “genuine” and “fake”). (b) Emotion category labeling task (a neutral option was not included in Exps. 1 and 2, since they did not include neutral faces). (c) Intensity rating task (0 was not included in Exp. 1 due to the absence of neutral faces). The example stimulus is from Langner et al. (2010; stimulus code Rafd090_01_Caucasian_female_angry_frontal).

Concerning our choice of scale anchors—genuine and fake—note that some researchers have used these particular terms (e.g., Krumhuber & Manstead, 2009; Langner et al., 2010), and others have used synonyms such as “authentic” (e.g., Thibault et al., 2009), “feeling” the emotion (McLellan et al., 2010), or “pretending” (e.g., Dawel et al., 2015; Del Giudice & Colle, 2007). Our use of “genuine” and “fake” was not based on any theoretical preference, but simply on the practical foundation that these terms would be the most meaningful to our participants: “Genuine” is a more common word than “authentic” in English (Kučera & Francis, 1967), and testing of our participants indicated that they found “fake” to be the best opposite to “genuine” emotion (see anchor validation task in Supplement S4). Also note, another practical advantage is that the RaFD faces were rated by Langner et al. (2010) using the terms “genuine” and “faked” and, because we tested the RaFD faces here, retaining this wording allowed for the best test of the validity of the neutral-midpoint scale (i.e., via correlation of our ratings with the previous Langner et al., 2010, ratings for the same items on their all-positive +1 to +5 scale).

Aim 1: norms for existing databases, and potential for dissociation between elicitation method, actual genuine emotion, and perceived emotion genuineness

Our first aim was to collect norms for two popular facial expression databases, testing all stimuli, or a fair sample of stimuli, showing our five target expressions. We included the PoFA (Ekman & Friesen, 1976) because it has dominated facial expression research for the past four decades (e.g., 3,876 citationsFootnote 2). The validity of the PoFA has traditionally been justified by evidence of high agreement about what emotion (happiness, sadness, etc.) these faces are showing (Ekman & Friesen, 1976). However, there are no previous data as to whether or not the expressions are perceived as genuine. One reason to think they might not be is that all of the negative expressions (anger, disgust, fear, sadness) from the PoFA were elicited by posing. In particular, they were created using the Directed Facial Action Task (Ekman, Levenson, & Friesen, 1983), in which people are instructed to pose particular facial muscle configurations, with no reference to the emotion word at all (i.e., no mention of “anger” or “sadness,” etc.; see Table 1 for a more complete description of the task). This is important because there is some evidence that deliberately posing expressions relies on different neural circuitry than facial expressions that are elicited spontaneously, as part of a genuine emotional response (Rinn, 1984). That said, there is no a priori guarantee that observers’ genuineness percepts will align with the method of elicitation. Indeed, dissociations between elicitation method, actual genuine emotion, and perceived genuineness could occur for many reasons. For example, it is possible that some posed expressions might include all the physical characteristics of real, genuinely felt expressions that are used by perceivers to judge genuineness. Or, alternatively, given evidence that the Directed Facial Action Task can induce the target emotion (e.g., via “facial feedback” or activation of an “affect program”Footnote 3), it is possible some posed expressions may actually reflect a genuine experience of emotion, which in turn might contribute to percepts of genuineness.

The PoFA images are grayscale and show people with outdated hairstyles. It is possible these factors could contribute to stimuli being perceived as fake (e.g., because potential cues to genuineness that involve color, like skin blushing, would be lost in grayscale images). Thus, we also included the RaFD (Langner et al., 2010) which, like the PoFA, was posed using the Directed Facial Action Task, but is more recent and uses color images. The RaFD is rapidly gaining popularity (e.g., 496 citations since publication in 2010Footnote 4).

We also collected norms for the only set, the McLellan faces (McLellan et al., 2010), in which the actual emotion of displayers has been verified by self-report, and that covers our five target emotions. The McLellan faces include event-elicited expressions in which the displayer reported feeling the target emotion (i.e., actually-genuine stimuli), and also posed expressions in which the displayer reported feeling no or minimal emotion (i.e., actually-fake stimuli; see Table 1 for details). Thus this database can be used to examine to what extent actual emotion, as well as elicitation method, is associated with perceived genuineness.

Aim 2: congruency of actual and perceived emotion, and developing a list of stimuli that are event-elicited and perceived as genuine

A subsequent experiment added perceived-genuineness norms for stimuli from more databases. Here, stimuli were specifically selected for their potential to produce congruency between observers’ perceptions and the actual emotional state of the person displaying the expression (to the extent that this could be known). For genuine, congruency would mean, for example, providing a list of sad faces that are perceived as showing genuine emotion and for which the displayer of the expression was really feeling sad (i.e., actual and perceived both genuine). For fake, congruency would mean sad faces that are perceived as showing faked emotion and for which the displayer of the expression was not feeling sad (specifically, feeling minimal, if any, underlying emotion). This congruence situation between perception and reality is the most theoretically simple, and thus likely to be of interest to the largest number of researchers.Footnote 5 For the McLellan faces, direct self-report of the expression-displayer’s emotion was available to establish how they were actually feeling. In other instances, information about the context and manner in which the expressions were elicited was used to infer whether the displayer was likely to be feeling the expressed emotion or not. This information included any experimenter instructions to the people displaying the expressions, and information relevant to determining whether the expressions had been elicited by a natural event (e.g., watching a funny movie). The top half of Table 1 details event-elicited sources in which emotions were likely to be genuinely felt by the people displaying the expressions, because the expressions were elicited in response to either real events that would be expected to evoke clear emotions (e.g., arguing with the referee during a sports game; watching a sad movie) or to mental simulations of emotional events (recalling an event from one’s life). The bottom half of Table 1 details posed sources (e.g., displayers instructed to make specific facial movements, or pretend the emotion, or practice the facial expression extensively before photographing), in which there is less likelihood that genuine emotion was experienced by the displayers.

The data from this second experiment are used to provide readers with a list of 143 stimulus items (covering all five emotions) that are congruent genuine—that is, expressions from event-elicited sources that were also perceived as showing genuine emotion.

Aim 3: matched perceived-as-genuine and perceived-as-fake stimulus sets

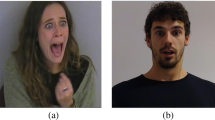

The data from the second experiment were also used to develop matched sets of stimuli—one containing 50 stimuli clearly perceived as genuine (from event-elicited sources), and the other containing 50 stimuli clearly perceived as fake (from posed-elicited sources). Specific criteria for establishing these new sets are outlined below. Figure 2 shows example matched-set face expression images from different image sources.

Example stimuli from the sources we tested (McLellan, Gur, FacePlace, News, RaFD, KDEF), illustrating the general appearance of the images from each database (the elicitation methods are described in Table 1), plus illustration of the pairings of stimuli for sex and viewpoint across our final (a) perceived-as-genuine set and (b) perceived-as-fake set. (c) Illustration of how the News faces were extracted from an emotionally congruent context image. (d) The PoFA stimuli (Ekman & Friesen, 1976) are not included for copyright reasons, but examples can be viewed at www.paulekman.com/product-category/research-products/.

Perceived genuineness

Concerning perception of emotion genuineness, we required that our perceived-as-genuine set be clearly and consistently perceived as showing genuine emotion, and our perceived-as-fake set be clearly and consistently perceived as fake. On our –7 to +7 genuineness rating scale, our specific criteria were as follows. First, in terms of relative scale values, we aimed to have the two sets maximally diverge from 0 (i.e., perceived-as-genuine stimuli selected to have the highest possible ratings, and perceived-as-fake stimuli selected to have the lowest possible ratings), with similar absolute value of the ratings (e.g., if the perceived-as-genuine angry faces had a mean rating of, say, +3, then perceived-as-fake angry faces would have a mean rating of approximately –3). Second, to verify the reliability of the absolute direction of genuineness ratings for the selected stimuli, we required that (a) in the perceived-as-genuine set, stimuli were rated as significantly genuine (i.e., rated significantly above zero), and (b) in the perceived-as-fake set, stimuli were rated as significantly fake (i.e., rated significantly below zero).

Congruence between perceived and actual genuineness

To maximize the likelihood of congruence between the emotion perceived by observers, and the actual emotional state of the person displaying the expression, we required that all perceived-as-genuine faces were from event-elicited sources, and all perceived-as-fake faces were from posed sources.

High labeling accuracy, at-least-moderate intensity, and matching the sets for intensity

We aimed for high labeling accuracy—that is, accurate categorization of expressions into the basic emotions of anger, disgust, fear, sadness, or happiness (Fig. 1b)—to ensure that observers recognized the expressions as belonging to the intended emotion category (defined as being in agreement with the original source information for the stimulus). Our specific criterion was ≥70 % correct labeling for each emotion category, for both our perceived-as-genuine and perceived-as-fake sets. We also aimed for similar overall labeling accuracy to that for widely used databases (such as the PoFA or RaFD; note that the typical finding in expression databases is that labeling accuracy is >95 % for happiness, and ranges from 61 % to 85 % for the other emotions; Langner et al., 2010; Palermo & Coltheart, 2004).

To achieve this labeling accuracy, we also required expressions to be of at-least-moderate intensity. We had observers rate faces for “How intense does this emotional expression look to you?” on a scale of 0 = none (for no emotion) and then 1 = weak to 9 = strong (Fig. 1c). We aimed to have intensity values around, or above, the midpoint of the scale, given that low intensity is known to reduce labeling accuracy (O’Reilly et al., 2016), and might also be expected to reduce observers’ ability to detect whether or not an expression is showing genuine emotion (e.g., because there might be insufficient physical information in the face).

Finally, we wanted mean intensity to be matched as closely as possible across the perceived-as-fake and perceived-as-genuine sets. Intensity matching is important to ensure that any differences researchers might find in responses to the two sets can be attributed to perception of the displayers’ emotion as genuine or fake (e.g., being more willing to help a person showing perceived-as-genuine sadness than a person showing perceived-as-fake sadness), and not to intensity differences (e.g., being more willing to help the person displaying the more intense expression).

Matching the perceived-as-genuine and perceived-as-fake sets on sex and viewpoint (and eye-gaze direction)

Our final criterion was that the perceived-as-genuine and perceived-as-fake sets be matched for sex and viewpoint. Regarding viewpoint, we were not able to match precise angle of the head but matched for whether the image was frontal or nonfrontal (approximately three-quarter) view; note that this procedure also indirectly matched eye-gaze direction (i.e., as looking approximately toward the observer vs. looking clearly away from the observer), because faces showed eyes looking straight ahead relative to the displayer’s head direction. Theoretically, sex and viewpoint/eye-gaze direction are important factors to consider because sex can affect what emotion a face is perceived as displaying (e.g., children are more likely to label boys as being “mad” and girls as being “scared”, irrespective of their actual facial expressions; Haugh, Hoffman, & Cowan, 1980), and eye-gaze direction can affect emotion labeling (Adams & Kleck, 2003) and judgments of emotion intensity (Adams & Kleck, 2005), and can also interact with expression processing in clinical conditions such as anxiety (Fox et al., 2007).

Matching for sex and viewpoint/eye-gaze direction was performed at the level of individual stimuli, by pairing items across the perceived-as-genuine and perceived-as-fake sets (as is illustrated in Fig. 2a and b). For example, for a given perceived-as-genuine female front-view face, we selected a matching perceived-as-fake female front-view face showing the same expression. Also note that sex was matched only across perceived-as-genuine and perceived-as-fake stimulus pairs within each emotion category. Sex was not matched across emotion categories (i.e., we have unequal proportion of females in the anger, disgust, fear, sadness, and happiness categories). This was because, in the context of requiring that expressions be perceived as genuine, we could find few females displaying anger at moderate-to-high intensity, and few males displaying disgust, fear, and sad expressions at moderate-to-high intensity. Thus most of our potential perceived-as-genuine stimuli were male for anger expressions and female for disgusted, fearful, and sad expressions. To give the final stimulus set widest applicability to various research questions, and given the relative ease of finding perceived-as-genuine happy faces, we then included a larger number of happy faces than other emotions in the final set, with a subset of male happy faces that researchers may find make a useful comparison set for the male angry faces, and a subset of female happy faces that researchers may find make a useful comparison set for the female disgusted, fearful, and sad faces.

An important noncriterion: the particular physical characteristics of the faces

One theme in the genuine-versus-posed literature has been whether particular physical characteristics of face stimuli—most notably whether or not a happy face includes facial action unit marker AU6 (crinkles around the eyes caused by contraction of orbicularis oculi, commonly termed the “Duchenne” smile marker)—are accurate signals that the displayer is feeling genuine emotion, and in turn whether observers will perceive a face containing these signals as displaying genuine emotion (e.g., Ekman, Davidson, & Friesen, 1990; Frank & Ekman, 1993; for a review, see Gunnery & Ruben, 2016). It is thus important to note that here we did not require specific facial action units (AUs) or other physical markers to be present in our perceived-as-genuine set (nor absent in our perceived-as-fake set). This is because, for emotions other than happiness, little is known about the physical attributes of faces that indicate genuine emotion. Concerning AUs, to the best of our knowledge there have been no empirical tests of what AUs are actually associated with genuinely felt expressions of emotion other than for happiness (although Ekman, 2003, has made some theoretical proposals), and results regarding which AUs drive perceptions of genuineness for different emotions are unclear. For sad expressions, studies directly contradict each other, with one suggesting that to be perceived as genuine sad expressions require the AU1+4 “inner brow raiser” plus “cheek lowerer” combination (McLellan et al., 2010), whereas another supported AU23 (“lip tightener”) rather than AU1+4 (Mehu et al., 2012). A single study (Mehu et al., 2012) has reported data for angry and fearful expressions, finding that observers perceive AU6 as a marker of genuine emotion for “hot” anger, and AU1+4 and AU15 (“lip corner depressor”) for genuine “panic” fear. These AUs notably overlap with those suggested to indicate genuine emotion for happiness (AU6) and sadness (AU1+4). No data are available regarding disgust. It is also plausible that actual or perceived genuineness could vary with multiple other physical factors, such as the symmetry of the expression (Ekman, 2003; Frank & Ekman, 1993), intensity of the expression (Dawel et al., 2015; Del Giudice & Colle, 2007; Thibault et al., 2009), and signs of underlying arousal such as pupil dilation and skin “blushing” (Levenson, 2014). However, little is known about the extent to which these factors might contribute differentially to genuineness percepts for different emotions, nor how they interact with each other, nor how they interact with AU-based markers (although the latter question has received some investigation for happiness; e.g., Dawel et al., 2015; Del Giudice & Colle, 2007; Gunnery & Ruben, 2016). Given this lack of established theoretical knowledge about physical markers for actual or perceived genuineness, we did not aim to select stimuli defined by any particular markers for our perceived-as-genuine set.

The present study

In summary, for the emotions of anger, disgust, fear, sadness, and happiness, the present study employed the new neutral-point rating method to obtain ratings of perceived genuineness, plus labeling accuracy and intensity ratings, for a total of n = 558 individual items. Given that it was not practically feasible to put all of these items and tasks into a single experiment (i.e., it would take too long per participant), we split up the items and/or tasks across four separate experiments (see Table 2). We began (Exp. 1) by obtaining norms for items from widely used databases (all PoFA items and a fair-sample subset of the RaFD), plus the only database for which the actual emotional states of the displayers are known (McClellan set). We next obtained genuineness ratings for a large number of stimuli from a wider range of databases, selected specifically for their potential to be perceived as either genuine from event-elicited sources (which we use to develop a list of 143 items of congruent genuine items) or fake from posed sources (Exp. 2). Finally, having selected, based on the results of Experiment 2, a set of 100 items to comprise an event-elicited perceived-as-genuine and a matched posed-elicited perceived-as-fake set, we then validated this set in the remaining two experiments (genuineness ratings and labeling accuracy in Exp. 3; intensity ratings in Exp. 4).

Method

Participants

Different observer samples were tested in each experiment (see Table 2 for details), but all were from a university community and mostly undergraduates, and would be expected to include a normal range of perceptual abilities related to emotion genuineness. All were Caucasian (i.e., “White”), to match the race of the face stimuli,Footnote 6 because there seem to be some race-related differences in percepts of emotion genuineness (e.g., at least some non-Caucasian groups do not interpret “Duchenne” crinkles around the eyes as a sign of genuine happiness; Thibault, Levesque, Gosselin, & Hess, 2012). Participation was remunerated via course credit or a small monetary payment ($15 per hour participation; session duration was Exp. 1 = 1.5 h per participant, Exp. 2 = 1.5 h, Exp. 3 = 1 h, Exp. 4 = 1.25 h).

Overview of Experiments 1–4

In Table 2, we summarize the structure of the experiments, including the databases and tasks included in each one.

Experiment 1

In the first experiment, we evaluated the perceived genuineness of stimuli from three databases in a systematic fashion, using all items, or a fair and representative sample of items. Specifically, from our five emotion categories, we tested all items from the PoFA and McLellan (as provided to us, T. McLellan, personal communication, 24 November, 2010), and a fair-sample sample of adult front-view female items from the RaFD. The RaFD database contains a very wide range of images (males, females, adults, children, three viewpoints, and three eye-gaze directions). Given practical limitations on the number of faces that could be rated, in Experiment 1 we tested only front-view adult females with direct eye-gaze (i.e., looking at the camera; note that we prioritized female over male faces, given suggestions that for many emotions females tend to be more expressive; Buck, Miller, & Caul, 1974; Kring & Gordon, 1998). The database contains 19 front-view direct gaze females for each of our five target expressions. We were able to include over half of these (i.e., ten images per expression). To ensure the subset we selected was representative of the full set, we sorted the stimuli on ratings of genuineness from Langner et al. (2010) and included every second stimulus in this sorted list (i.e., comprising the stimulus with highest genuineness rating for that emotion, the stimulus with the third-highest rating, the fifth-highest rating, etc.).

Experiment 1 also collected genuineness ratings for some naturalistic angry and happy expressions taken from Australian news media. Faces were extracted from photographs showing professional sportsman involved in an altercation with the referee or with players from the opposing team for anger (five items) or celebrating a victory for happiness (seven items; see the examples in Fig. 2c and Supplement S5). The original photographs were purchased from Australian news media company Fairfax (www.fairfaxsyndication.com/C.aspx?VP3=CMS3&VF=FXJO50_1). For evidence of the congruence between the displayed facial expression and the background context, see Supplement S5. (We also provide FACS coding of these faces, given they have not previously been used in research; see Supplement S6 for details.)

Experiment 2

In Experiment 2, we collected genuineness ratings for stimuli from additional sources (FacePlace, Gur, Karolinska Directed Emotional Faces [KDEF]). Here, we deliberately selected items that looked more genuine from event-elicited sources, or more fake from posed sources, in the hope that they would be suitable for developing our list of stimuli that are perceived as genuine and our new stimulus sets. We also retained items from Experiment 1 that had potential for our list and the new stimulus sets (i.e., that were rated as clearly genuine or fake), but excluded PoFA items because these were black and white, and all other stimuli were colored.

Note that, for some emotions, it was relatively easy to obtain perceived-as-genuine event-elicited stimuli meeting our at-least-moderate intensity requirements within existing databases—particularly, for happiness, sadness, and disgust. However, this was very difficult for anger and fear. For anger, we were able to use the event-elicited News images from Experiment 1, because anger is an emotion that is sometimes displayed at professional sports events, where professional photographers are present and take high-resolution images. Searching media and general web outlets revealed that high-resolution real-world photographs of fear (in real fear-inducing contexts) are very rare. As a result of these difficulties, we ended up with fewer fear and anger stimuli in our testing than for the other emotions.Footnote 7

Experiments 3 and 4

Finally, we ran two validation experiments in new samples of observers, to confirm the suitability of our matched perceived-as-genuine and perceived-as-fake sets (as selected from the Exp. 2 results, in accordance with the procedure outlined in Supplement S7). Experiment 3 collected genuineness ratings and labeling accuracy (for a larger number of participants than used for these tasks in Exp. 2; see Table 2), while Experiment 4 collected intensity ratings (for all stimuli tested in Exps. 2 and 3; note that we did not include intensity ratings in Exps. 2 and 3 because this would have made those experiments too long). We also added a small number of neutral expression stimuli (Supplement S1 gives database, viewpoint and sex information). This allowed us to assess labeling accuracy for the proposed perceived-as-genuine and perceived-as-fake sets when participants were not forced to choose an emotion (i.e., they could choose “neutral”), and to compare intensity ratings for our emotional stimuli with those for neutral stimuli.

Experimental procedure

Stimuli

All of the face stimuli (examples are shown in Fig. 2) were static images, cropped to standard dimensions so that the face took up most of the frame. Presentation size was 6.9° × 9.1° at a viewing distance of 50 cm. Backgrounds to the faces were all white, with the exception that in Experiment 1 we kept the original gray backgrounds for the PoFA stimuli and placed the News faces on a similar gray background (so that the PoFA stimuli did not stand out on this basis). Tears were removed from crying faces because these could potentially be used to make a top-down, reasoned judgment, without participants perceiving genuineness in any bottom-up fashion from the face itself (e.g., note that tears could drive a top-down “it must be genuine” response even if the faces were shown inverted). A general criterion for all stimuli was that the resolution of the photograph had to be sufficiently good that the image would be suitable for studies using typically-sized face stimuli (i.e., similar to the size we used here). Table 3 summarizes the stimuli tested in each experiment.

Experimental tasks

For all tasks: each face was shown one at a time in the center of the screen; faces were presented in a different random order for each participant; and the face remained onscreen until response. Participants were given a short break (minimum of 30 s) after approximately 100 trials.

Genuineness ratings and emotion labeling (Exps. 1, 2, and 3)

Participants were given detailed written instructions explaining the concept of emotion genuineness and what they needed to rate. Participants were told to read the instructions carefully because they would be quizzed on them later. The instructions were as follows:

Sometimes people show facial expressions of emotions they genuinely feel, and sometimes they display expressions that are faked or posed (e.g., to be polite or because they are acting). An example of a genuine expression is when somebody smiles and they really feel happy, like when they get a present or see something funny. An example of a faked expression is when somebody smiles for a school photo, without feeling any emotion. Or a parent playing a game with their child may put on a “scared” face to pretend fear, but is not actually feel the emotion displayed. Your task is to decide whether faces are showing genuinely felt expressions or faked/posed/acted expressions.

All the expressions you will see were photographed in laboratories,Footnote 8 but some of them are genuine and some are faked. In genuine expressions, emotions were induced by showing people video clips, pictures or sounds, or by asking them to remember an emotional event. For example, some people showing genuine happy expressions were photographed while watching a funny video. Others showing genuine fear were photographed while watching a scary film. In faked expressions, people were simply instructed to act different emotions. For example, some people showing faked happy expressions were photographed when instructed to pose for a photo. Others showing faked fear were photographed when instructed to “look scared” or to move specific face muscles.

You will rate each face using the following scale: [scale shown here; see Fig. 1a] –7 means you think the expression is completely faked/posed/acted, and that the person does not feel the displayed emotion at all. +7 means you think the expression is completely genuine, and that the person really feels the displayed emotion. 0 means that you can’t tell at all, and are just guessing.

Please don’t assume that half the faces you see will be genuine and half faked—this is not true of the face set you will see. We just want to know how genuine or fake you think the expressions are. If you think that more of the faces you see are at the genuine end of the scale, please use this end more. If you think that more of the faces you see are at the fake end of the scale, please use this end more. If you think that they are spread across the scale, then please use the full length of the scale.

A final point: we want you to ignore the strength of the expressions when you rate how genuine or fake each expression is. For example, an expression of sadness may be very subtle but be completely genuinely felt. Such an expression should be rated as completely genuine. On the other hand, an expression of sadness may be very strong but be completely faked/posed/acted. Such an expression should be rated as completely faked.

For each face, participants rated the genuineness of the emotion displayed (Fig. 1a) and labeled the emotion (Fig. 1b) before moving onto the next stimulus. Participants labeled the basic emotion category they believed the expression represented by selecting one of five label options (“anger,” “disgust,” “fear,” “happy,” “sad”) in Experiments 1 and 2, or one of six label options in Experiment 3 (neutral expressions were included, so a “neutral” option was added). Collecting emotion labeling data in conjunction with genuineness ratings allowed us to ensure that genuineness ratings applied to the correct emotion (e.g., where the face displayed anger, the participant was rating genuineness of anger, not some other emotion). Genuineness rating trials were excluded where the emotion was incorrectly labeled by that participant (≤15 % of trials in each experiment).

Intensity ratings (Exps. 1 and 4)

For each face, participants rated the intensity of the emotional expression displayed, as is shown in Fig. 1c.

Results

Norm data for every individual stimulus we tested (n = 558) are provided in an Excel file in Supplement S1. This includes genuineness ratings, intensity ratings, emotion labeling accuracy data, plus image codes from the source databases.

Validation of genuineness rating scale: consistency with previous RaFD ratings and across our experiments

Before turning to the results of primary interest, we present evidence supporting the validity of our new genuineness rating task. First, we examined correlations between our ratings for the RaFD stimuli and previous ratings from Langner et al. (2010) to ensure our move to include a neutral midpoint in our scale did not alter observers’ judgments of the relative genuineness of stimuli. We used the RaFD items for this purpose because we tested a substantial number of these stimuli, and Langner et al. (2010) provide genuineness ratings for these same stimuli from a traditional all-positive scale (+1 = faked, +5 = genuine) with which we could compare our data. As desired, using mean ratings for each stimulus item, we found a high correlation between Langner et al.’s (2010) ratings and ours: r(50 items) = .82, p < .001 (Exp. 1); r(44 items) = .79, p < .001 (Exp. 2). This indicates good agreement of the relative ratings.

Second, we examined the stability of the genuineness ratings across our experiments for stimuli that were tested more than once. This was important because the total stimulus set varied between experiments, so that a particular repeated item was being rated against a different comparison set of other items (and by different observers), which could, in principle, affect the rating given to that item. The results indicated that the relative ratings were highly stable across experiments, with correlations between items always exceeding .93, all ps < .001 [Exps. 1 and 2, r(46 items) = .933; Exps. 1& 3, r(17 items) = .978; Exps. 2 and 3, r(93 items) = .974]. We also found that absolute ratings (i.e., whether a stimulus was rated above or below 0) were stable across our experiments. Of the 124 stimuli rated for emotional genuineness in more than one experiment, 107 stimuli (86 %) were always rated in the same direction (i.e., always above 0 or always below 0). For the remaining 17 stimuli (14 %), ratings were in different directions for different experiments (i.e., above 0 for one sample but below 0 for another sample) but in almost all cases this arose where the percept was ambiguous (i.e., ratings very close to zero): only one stimulus changed from being rated as significantly genuine (Exp. 1) to being rated as significantly fake (Exp. 2). Overall then, these results argue ratings of perceived genuineness were stable across our different experimental samples.

Experiment 1: norms for complete or fair-sample face sets

Figure 3 presents the genuineness ratings from Experiment 1 by source (PoFA, RaFD, McLellan, News). Figure 3a shows the ratings at the level of the whole emotion category (i.e., averaged over all items for that emotion, and then over participants), and Fig. 3b shows the ratings for individual stimuli within that emotion category (i.e., averaged only over participants).

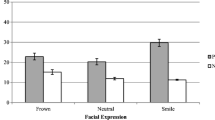

Genuineness ratings from Experiment 1 (n = 37 observers). (a) The top row shows the perceived genuineness for each emotion category overall (i.e., averaged across all items in the category and then across all participants) for (i) all stimuli from the PoFA (Ekman & Friesen, 1976); (ii) a fair sample of RaFD frontal-view female faces (Langner et al., 2010); (iii) all stimuli from McLellan (T. McLellan, personal communication, November 24, 2010; McLellan et al., 2010); and (iv) our News faces. (b) The bottom row shows the perceived genuineness for individual stimulus items (i.e., averaged only over participants). ANG = angry, DIS = disgusted, FEA = fearful, SAD = sad, HAP = happy. Error bars show ±1 standard error of the mean (SEM). *p < Bonferroni-corrected alpha (corrected for number of emotion categories). ns = nonsignificant, either for comparison to zero (stars above/below each bar) or for comparison between event-elicited and posed stimuli for the McLellan set (brackets across the tops of condition pairs). 1Data from Ekman (1980)

In addition to providing normative data, we were able to address some questions of theoretical interest with our results, noting that, because we tested complete (PoFA, McLellan) or fair-sample (RaFD) stimulus sets for our five emotions, we can draw some conclusions about each database in its entirety. We start here by examining the extent to which the popular PoFA and RaFD stimuli, all of which were posed using the Directed Facial Action Task (Ekman et al., 1983) except for the PoFA happy expressions (Ekman, 1980), are perceived as genuine (i.e., ratings significantly above zero) versus fake (i.e., ratings significantly below zero). Analyses were conducted at the level of the whole emotion category, by comparing the mean genuineness rating for each emotion for each set to zero. Alpha was set to .01 to Bonferroni-correct for the five emotions, and we used two-tailed tests.

PoFA (Ekman & Friesen, 1976)

Figure 3a-i shows that of the four PoFA expressions that were posed via the Directed Facial Action Task, three were perceived as fake—namely, the angry, disgusted, and fearful expressions, all ps < .001. The remaining negative expression, sad, was perceived as slightly in the genuine direction, although nonsignificantly after Bonferroni correction, p = .038. On the other hand, the happy expressions—the only stimuli in the PoFA set that were elicited spontaneously during natural social interactions (Ekman, 1980)—were perceived as genuine, p < .001. PoFA happy expressions were also perceived as being significantly more genuine than all four negative PoFA expressions, all ps < .001.

RaFD female faces (Langner et al., 2010)

Figure 3a-ii shows that four of the five RaFD expressions were perceived as fake—namely, those for anger, disgust, fear, and sadness, all ps < .001. The RaFD happy category was perceived as slightly, but not significantly (p = .154), in the genuine direction. These results add considerable extra information over and above the genuineness ratings obtained for the RaFD by Langner et al. (2010): for example, on their +1 to +5 scale, their mean rating of 2.89 for the ten angry faces that we tested could be interpreted as indicating either perceived as genuine (if participants assigned 1 to mean fake, and all numbers greater than 1 to mean some degree of genuineness), or perceived as fake (if participants implicitly chose to use 3 as a neutral point). The present result resolves this ambiguity by showing that these angry faces are perceived as fake.

McLellan (T. McLellan, personal communication, November 24, 2010; McLellan et al., 2010)

For the McLellan faces, we were able to examine the extent to which percepts of genuineness align with actual emotion genuineness, since we know how the displayers were actually feeling (i.e., via self-report). Overall, the results showed that perceived genuineness was often dissociated from actual emotion genuineness. For actually-genuine stimuli, only two of the five expression categories were perceived as genuine—namely, happiness and disgust, both ps < .01. For actually-fake stimuli, only one of the five expression categories was perceived as fake—namely, sadness, p < .001. All of the remaining conditions were rated not significantly different from zero (actually-fake fear p = .069 in the wrong [i.e., genuine] direction; all other ps > .276), indicating that participants perceived the emotional genuineness of these stimuli as ambiguous. A series of t tests within each emotion category, comparing the genuineness ratings for the actually-genuine versus the actually-fake conditions, revealed significantly higher genuineness ratings for the actually-genuine than for the actually-fake stimuli for sadness and happiness (both ps < .001). However, neither of these differences reflected congruency between the perceived and actual emotion (i.e., the actually-genuine stimuli being perceived as genuine and the actually-fake stimuli being perceived as fake); instead, in each case one type of stimulus was perceived in the desired direction but the other was perceived as ambiguous (i.e., actually-genuine sadness and actually-fake happiness were rated near zero). Furthermore, for anger, disgust, and fear, there was no significant difference in the ratings between the actually-genuine and actually-fake stimuli (ps > .02, which was nonsignificant with Bonferroni correction), and indeed for fear the trend was in the wrong direction (see Fig. 3a-iii).Footnote 9 Overall, then, in the McLellan set of stimuli, observers were commonly unable to pick out the actual underlying emotional state of the displayer.

News

Here we were interested in whether stimuli that were perceived as clearly genuine might be accessible from other naturalistic sources, such as news media. Indeed, our News faces—angry and happy faces captured during spontaneous displays of emotion in real-world sports games—showed good potential for obtaining stimuli that are perceived as clearly genuine. At the level of the whole category (Fig. 3a-iv), genuineness ratings were substantially and significantly above zero for both anger and happiness, both ps < .001 (alpha set to .025 to Bonferroni-correct for the two emotion comparisons). Also, the anger set was perceived as being as strongly genuine as the happiness set (no difference between the means, p = .216). Also note that the individual News stimuli (Fig. 3b-iv) were all rated as clearly genuine (ratings > +3). Thus, overall, observers clearly perceived the emotion displayed in the News faces to be genuine.

Experiment 2: genuineness ratings for a broader stimulus items

Figure 4 shows genuineness rating results for each of the n = 398 stimuli that survived the pilot-testing step, described in the Experiment 2 flow chart in Supplement S7.

Mean genuineness ratings for individual stimuli from Experiment 2 (n = 31 observers, 398 stimulus items) (a) used to select items for the perceived-as-genuine set and (b) used to select items for the perceived-as-fake set. IMPORTANT NOTE: Some of the more extremely rated posed stimuli were not included in the perceived-as-fake set because they were not matched on sex or viewpoint with the perceived-as-genuine items, or to ensure that the absolute ratings for the two sets were as similar as possible. Note also that the ratings for these specific stimuli should not be taken as indicative of how observers would perceive these source databases as a whole: The items were selected to be deliberately biased in the perceived-as-genuine direction for the event-elicited databases, and deliberately biased in the perceived-as-fake direction for the posed databases. ANG = angry, DIS = disgusted, FEA = fearful, SAD = sad, HAP = happy, // = no stimuli for some emotion categories for some sources.

Congruent genuine items: list of all event-elicited stimuli that were perceived as genuine

Supplement S2 lists all event-elicited stimuli that had a genuineness rating greater than 1 for all samples that rated that stimulus (total n = 143 of 191 event-elicited stimuli tested). This list comprises eight anger, 20 disgust, 11 fear, 35 sadness, and 69 happiness items, with corresponding details that would be useful for researchers to select particular stimuli such as source, emotion, sex, viewpoint, labeling accuracy, and intensity ratings. This list can be used by researchers who require “congruent genuine” expression stimuli, defined as being both event-elicited (i.e., so it can reasonably be presumed that the actual emotion was genuinely felt by the displayer) and perceived by typical observers as showing genuine emotion (but where a matched perceived-as-fake set is not required). The list also includes image codes from the source database, and how the images can be accessed for future research.

Selection of stimuli for the perceived-as-genuine and perceived-as-fake sets

Stimuli for our matched perceived-as-genuine and perceived-as-fake sets were selected in accordance with the flowchart in Supplement S7. Where stimuli were selected from Experiment 2, they are marked as red circles in Fig. 4 (all 50 stimuli in the perceived-as-genuine set; 43 of the stimuli in the perceived-as-fake set, which also included seven additional RaFD items not tested in Experiment 2 but selected on the basis of ratings from Langner et al., 2010). Each set comprised six angry, ten disgusted, six fearful, 12 sad, and 16 happy items (total = 50 items in each set, including 80 different identities). Readers will note that, from Fig. 4, these were not always necessarily the very best items, defined by genuineness ratings alone (i.e., not always the most genuine for the perceived-as-genuine, and the most fake for the perceived-as-fake set); this was due to the need to additionally match across sets for sex, viewpoint, and intensity. Supplement S3 provides full details of each image included in the final matched sets, including genuineness and intensity ratings, emotion labeling accuracy, sex, viewpoint, eye-gaze direction, image codes from each source database, and how the images can be accessed for future research.

Experiments 3 and 4: validation of perceived-as-genuine and perceived-as-fake sets

Figures 5, 6 and 7 show validation data for the 100 items in our final sets.

Genuineness ratings from Experiment 3 for the final perceived-as-genuine and perceived-as-fake sets (n = 94 observers; 100 stimulus items). (a) Perceived genuineness for each emotion category (i.e., averaged across all items in the category and then across all participants), demonstrating that, for all five emotions, the perceived-as-genuine set are rated as genuine (ratings significantly above zero) and the perceived-as-fake set are rated as fake (ratings significantly below zero). (b) Ratings for individual stimuli (averaged only over participants). Results are shown by sex of the face only for happy stimuli because there were insufficient numbers of stimuli of each sex for the other emotions to warrant examining the data separately (i.e., ANG = two females, four males; DIS, FEA, SAD = all female). ANG = angry, DIS = disgusted, FEA = fearful, SAD = sad, HAP = all happy stimuli, HAP: males = happy male stimuli, HAP: females = happy female stimuli. Error bars show ±1 standard error of the mean (SEM). *p < Bonferroni-corrected alpha, either for comparison to zero (stars above/below each bar) or for comparison between the perceived-as-genuine and perceived-as-fake stimuli for a given emotion category (brackets across the tops of condition pairs).

Emotion labeling accuracy (% correct) for (a) the final perceived-as-genuine and perceived-as-fake sets, averaged over participants and stimulus items (for the labeling accuracy for individual items, see Supplement S2) from Experiment 3 (n = 94 observers), along with (b) comparison labeling accuracy for the PoFA and RaFD from Experiment 1 (n = 37 observers). In this type of “bubble” diagram, the circles on the diagonal indicate the correct labeling responses (i.e., percentages of occasions on which sad faces were correctly labeled by participants as “sad,” etc.) and the off-diagonal circles provide the confusion matrix for incorrect responses (e.g., percentages of occasions on which sad faces were mislabeled as, say, “disgust”). The size of each circle reflects how frequently that pattern of responses occurred. ANG = angry, DIS = disgusted, FEA = fearful, SAD = sad, HAP = happy.

Intensity ratings (a) for our final perceived-as-genuine and perceived-as-fake sets, averaged over participants and stimulus items (for the intensity ratings for individual items, see Supplement S2) from Experiment 4 (n = 25 observers), along with (b) comparison intensity ratings for the PoFA and RaFD stimuli from Experiment 1 (n = 37 observers). ANG = angry, DIS = disgusted, FEA = fearful, SAD = sad, HAP = happy, NEU = neutral. Error bars show ±1 standard error of the mean (SEM). *p < .01. ns = nonsignificant.

Genuineness ratings (Exp. 3)

At the level of the whole emotion category (Fig. 5a), statistical analysis confirmed that the ratings for every category were significantly above zero for the perceived-as-genuine set (all ps < .001) and significantly below zero for the perceived-as-fake set (all ps < .001, including for happiness; note that we used alpha = .01 within each set). Also, for every emotion category, t tests showed that the perceived-as-genuine set was rated as significantly more genuine than the perceived-as-fake set (all ps < .001).

Comparing the degree to which the event-elicited stimuli were perceived as genuine with the degree to which the posed stimuli were perceived as fake, Fig. 5a shows that the ratings for the two sets are approximately symmetric on either side of 0 for four of the emotions—namely, the four negative emotions of anger, disgust, fear, and sadness (i.e., for these emotions, the light gray bars are approximately as far above zero as the dark gray bars are below zero). For happiness, however, this was not the case: Fig. 5a shows that the event-elicited happy expressions were perceived as clearly genuine, but the posed happy expressions were perceived as only very slightly fake. Note we were not able to find a better perceived-as-fake happy set because, across all the n = 76 posed happy stimuli that we tested across Experiments 1–3, the great majority of posed happy stimuli were perceived as being either genuine or ambiguous, and few were perceived as fake (only 17 % of the posed-happy stimuli had genuineness ratings below –1, and 5 % below –3, relative to 42 % in the –1 to +1 range and 40 % with ratings above +1). (We consider possible theoretical reasons for this result in the Discussion.) Splitting happy faces into our male and female subsets (since these provide better matches for our mostly male angry and all-female disgusted/fearful/sad faces, respectively) revealed results similar to those in the full set of 16 happy faces (right panel of Fig. 5a).

Figure 5b shows the results for the individual stimuli, and Supplement S3 presents statistical results comparing each individual stimulus rating to zero. For the perceived-as-genuine set (Fig. 5b-i), all 50 individual stimuli were perceived as showing significantly genuine emotion (i.e., t tests showed that the ratings were significantly above zero; 49 in Exp. 3, and one combining the Exp. 2 + 3 participants to maximize the sample size). For the perceived-as-fake set (Fig. 5b-ii), from the four negative-valence emotions (anger, disgust, fear, and sadness), all stimuli were rated in the fake direction, and 34/35 were perceived as being significantly faking emotion (i.e., t tests showed that ratings were significantly below zero). For happiness, 5/16 stimuli were perceived as significantly fake, and 10/16 were perceived as ambiguous with respect to emotional genuineness (i.e., ratings not significantly different from zero). The final, 16th happy item was problematic, in that it was perceived as slightly but significantly in the genuine direction. Supplement S3 suggests a possible replacement item, or users may simply choose to drop this 16th item, and its perceived-as-genuine pair item, given that our final set includes more happy stimuli than stimuli for other emotions.

In summary, concerning the perceived genuineness of the emotions displayed in our final set, we created a good set of perceived-as-genuine expressions from event-elicited sources for all emotions (anger, disgust, fear, sadness, and happiness). We also have a good set of perceived-as-fake expressions from posed sources for four of the five emotions (anger, disgust, fear, and sadness). For happiness, we have a perceived-as-fake set that were perceived as more ambiguous than clearly fake, although significantly in the fake direction when analyzed at the level of the whole category of items. Also note that the happy stimuli from posed sources are still perceived as significantly less genuine than our perceived-as-genuine happy set (p < .001).

Emotion labeling accuracy (Exp. 3)

Figure 6 presents labeling accuracy results for our perceived-as-genuine and perceived-as-fake sets. Averaging across all items in each emotion category, Fig. 6a shows that the mean labeling accuracy was high for all emotions in both our perceived-as-genuine set (ranging from 71 % correct for fear, to 96 % for happiness) and our perceived-as-fake set (ranging from 83 % for fear, to 93 % for happiness; chance = 16.7 %, given the choice of five emotions plus neutral), and approached or matched that of the PoFA and RaFD (our sets in Fig. 6a: averaged across all emotions, perceived as genuine = 84 % correct, perceived as fake = 90 %; Fig. 6b: PoFA = 87 %, RaFD = 90 %).

Although the labeling accuracy was sufficiently high for each emotion for both our sets to meet our criterion of >70 % accuracy, and thus to ensure they could be usefully categorized, we note that there was a tendency for labeling accuracy to be higher for the perceived-as-fake set than for the perceived-as-genuine set: A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA; 5 Emotions × Genuine/Fake) on the accuracy data from Experiment 3 showed a main effect of set, F(1, 93) = 88.91, MSE = .021, p < .001 (mean accuracy across the five emotions = 80.2 % for perceived as genuine, 89.1 % for perceived as fake) that was qualified by a significant interaction between emotion and set, F(4, 372) = 19.65, MSE = .023, p < .001. Together, these results indicate that labeling accuracy was better for the perceived-as-fake set than for the perceived-as-genuine set overall, but that this effect varied significantly with emotion category. A series of t tests then compared the perceived-as-genuine with the perceived-as-fake set for each emotion, with alpha set to .01 to Bonferroni-correct for the five emotion comparisons. For all the negative emotions, the perceived-as-fake sets were labeled more accurately than the perceived-as-genuine sets, all ps < .01. For happiness, however, the perceived-as-fake set was labeled less accurately than the perceived-as-genuine set, p = .001.

Intensity ratings (Exp. 4)

Figure 7a shows that expressions from all emotion categories were rated as at least moderate in intensity (i.e., ratings at or above the midpoint of the scale; also note the very low intensity rating for neutral confirms the validity of this interpretation). Intensity was also similar to that for the PoFA and RaFD faces (Fig. 7b).

Ideally, we also aimed to equate the rated intensities of the perceived-as-genuine and perceived-as-fake sets. This aim was satisfied at the level of the complete sets (i.e., averaged across all five emotions): a two-way ANOVA (5 Emotions × Genuine/Fake) showed no main effect of set, F(1, 24) = 0.89, MSE = .60, p = .354 (mean intensities across the five emotions = 5.25 for perceived as genuine, 5.15 for perceived as fake). For some individual emotions, the matching was only approximate rather than perfect. The ANOVA revealed a significant interaction between emotion and set, F(4, 96) = 52.81, MSE = .31, p < .001. Our t tests then compared the perceived-as-genuine with the perceived-as-fake set for each emotion, with alpha set to .01 to Bonferroni-correct for the five emotion comparisons. For anger, the intensities of the perceived-as-genuine and perceived-as-fake sets did not differ significantly, p = .513. For the happy and sad expressions, the perceived-as-genuine sets were more intense than the perceived-as-fake sets, both ps < .001. For the disgust and fear expressions, the perceived-as-genuine sets were less intense than the perceived-as-fake ones, both ps < .002. Thus, there are some small differences in intensity for the individual emotions that researchers may want to consider in statistical analyses (e.g., by including the intensity information given for individual items in Supplement S3 as a covariate in the analysis).

Discussion

Our results offer several contributions. First, face expressions generated using the Directed Facial Action Task procedure (RaFD, PoFA negative expressions) are often perceived as fake (Exp. 1). Second, event-elicitation, and indeed even confirmed actual felt emotion (McLellan faces), does not guarantee that expressions will be perceived as genuine (Exps. 1 and 2). Third, via the inclusion of items from multiple source databases (Exp. 2), it was possible to develop a list of 143 congruent genuine items, specifically event-elicited expressions that are perceived as genuine (Supplement S2), as well as to provide norm information for many more stimulus items (total n = 558 across all experiments; see Supplement S1).

Finally, results from Experiments 3 and 4 show we have successfully established matched perceived-as-genuine and perceived-as-fake stimulus sets (Supplement S3)—from, respectively, event-elicited and posed sources—with the following properties. For the perceived-as-genuine set, all emotion categories (anger, disgust, fear, sadness, happiness) are perceived as showing genuine emotion, both at the level of the whole category (i.e., averaged across all stimulus items within each emotion), and for each of the 50 stimulus items individually. For the perceived-as-fake set, the four negative emotions (anger, disgust, fear, sadness) were perceived as not showing genuine emotion, both at the level of the whole category and for almost all individual items (34/35), and the happy set were perceived mostly as ambiguous (and significantly but slightly fake on average). For both sets, the items were also demonstrated to be of at-least-moderate intensity (and of similar intensity to PoFA and RaFD) and to be accurately labeled in terms of the basic emotion (accuracy ranging from 71 %–96 % correct for different emotions). In addition, the perceived-as-genuine set is matched to the perceived-as-fake set (within each emotion category) for face sex (male, female), face viewpoint (frontal vs. three-quarter), approximate eye-gaze direction (i.e., looking approximately toward the camera vs. looking clearly away), and intensity (particularly at the level of all emotions combined), ensuring researchers can be confident that any apparent genuine-versus-fake differences found using our sets are due to perceived genuineness rather than to confounds with these other important variables.

Implications of our results for various theoretical issues

Although the primary aims of this study were to collect normative data and develop stimulus sets, our results do have a few implications for theoretical issues as follows.

Percepts of genuineness do not necessarily match elicitation methods, nor actual emotional states

Our present results indicate that observers’ perceptions of genuineness do not necessarily match either elicitation methods or actual emotion states. On average, event-elicited stimuli are more likely to be perceived as showing genuine emotion than posed stimuli. However, Figs. 3 and 4 show multiple cases of stimuli that were posed yet perceived as reflecting genuine emotion (particularly for happiness) or were event-elicited yet perceived as fake. Intuitively, expressions displayed by people actually feeling the corresponding emotion might be expected to be perceived as genuine more often, yet Fig. 3 shows this was often not the case for the McLellan facesFootnote 10 (although note we are not suggesting observers can never do this; for example, our angry sportsmen were very likely feeling the displayed emotion and observers had no trouble picking that up). Finally, note that elicitation method and actual emotional state are also not necessarily associated. For instance, an event may not lead to all people feeling the same emotion (notwithstanding differences in intensity) and posing an expression through physical muscle movements can sometimes induce an actual corresponding emotion (Levenson et al., 1990; Niedenthal, Mermillod, Maringer, & Hess, 2010).

This potential for a three-way dissociation between elicitation method, emotion felt by the displayer, and emotion perceived by the observer means that researchers need to be clear about which of these three variables they wish to study, and whether they have suitable stimuli to do so. Here, we have started from the position that stimuli that lead to known states of perception (in typically developing young adult observers) are of interest in many research questions because in the real world observers do not have direct access to another persons’ emotions and so their responses to that person will often be driven by their percept of others’ emotion (rather than directly by actuality, except perhaps where this can be detected implicitlyFootnote 11). We also note that, when researchers wish to study the processing of actual emotional states, to our knowledge the only available database suitable for this purpose (containing emotions beyond happiness) is the McLellan set.

Posed happy expressions are rarely perceived as truly fake

A potentially surprising finding that emerged from our new neutral-midpoint rating scale is that it is very difficult to obtain happy expressions that are perceived as fake. Most of the posed happy expressions were perceived as ambiguous or even as showing genuine emotion. Although this finding might seem at odds with previous evidence that adults and children perceive some smiles as more genuine than others (Frank & Ekman, 1993; Gunnery & Ruben, 2016), our results are consistent with these previous findings: we were able to find smiles that were perceived as clearly more genuine than other smiles (i.e., there is a relative difference). A new finding derived from the use of our novel rating scale is that, in absolute terms, posed smiles are typically perceived as ambiguous, not as definitively fake.

We can see three general types of explanations for this result. The first relates to the Levenson et al. (1990) finding that people posing happy expressions (via the directed facial action instructions) actually feel happy on approximately 50 percent of occasions, which is more often than for other emotion categories. Thus it may be that observers are correctly picking up that some degree of genuine emotion is present. The second possibility is that displayers might be more successful at creating a convincing simulation of happiness than of other emotions, perhaps due to greater practice in everyday life: we often pose smiles for photos or to greet someone, and an important social skill is to convince others you are happy when you are not (e.g., about receiving a present you don’t like). In comparison, people less frequently need to pose other types of emotional expressions, and their intent is often not to convince an observer they are genuine (e.g., a parent playing at being an angry tiger with their child specifically does not want the child to believe they are actually angry). The third possibility is that smiles often indicate a positive-valence state or prosocial intentions (e.g., a willingness to be polite and helpful; Niedenthal et al., 2010) rather than the actual emotion of happiness, and observers might be responding to the genuineness of the positive social message being conveyed.

This finding also highlights that there are potentially important differences in the types of situations in which different emotions might be posed, that could be important for understanding how perceived genuineness interacts with emotion category. While happiness, for example, is likely to be posed for affiliative reasons (e.g., being polite), it is difficult to see when it would be polite to feign anger or fear. Instead, these emotions might only be posed in play or, in the case of anger, to get somebody else to behave in an appeasing way.

What physical attributes of facial images or expressions contribute to percepts of genuineness?

Our study was not designed to test this question, but we can draw a few simple conclusions from our results. First, concerning image properties, we note that being in black and white does not prevent an expression from being perceived as showing genuine emotion (as demonstrated by the ratings for the PoFA happy stimuli in Fig. 3), and nor does any particular viewpoint or eye-gaze direction limit perceptions (e.g., we found perceived-as-genuine images across three-quarter views, frontal views, and frontal views specifically making direct eye contact with the camera, and perceived-as-fake images also across all three types).

Second, turning to the appearance of the facial expression itself, there must logically be some forms of physical difference that lead some expressions to be perceived as genuine and others not. Our present results are consistent with previous authors’ views (e.g., Frank et al., 1993; Frank & Ekman, 1993) that the “core” AUs sufficient to define the basic category of an expression (i.e., as anger, fear, happiness, etc.; Ekman, Friesen, & Hager, 2002) are not, by themselves, sufficient to cause an expression to be perceived as showing genuine emotion; for example, all the PoFA stimuli in Fig. 3 contain these core AUs, but observers consistently perceived most of the negative-valence stimuli as fake. For happiness in Caucasian observers, it is well established that one relevant additional marker of genuineness is AU6 (i.e., present in addition to the other “core” AUs for happiness; Gunnery & Ruben, 2016). As we noted in the introduction, much less is known about additional AU markers for genuineness for other emotions, and further cues to genuineness likely exist that are not AU-based (e.g., symmetry, or indicators of arousal such as blushing and pupil dilation). Our present results do say something about one previous idea, namely the proposal that AU1+4 is associated with genuinely felt sadness (Ekman, 2003; McLellan et al., 2010). Given that the proposed AU1+4 genuineness marker is present in all of the McLellan event-elicited sad faces (and absent in all of the posed sad faces; see McLellan et al., 2010), our results showing that these images are perceived as ambiguous rather than genuine indicate that AU1+4 is not a sufficient marker for the percept of genuineness for sadness (in agreement with Mehu et al., 2012).

In the PoFA set, are the differences between happiness and other emotions due to valence or perceived genuineness?

Previously, where researchers have observed differences for happiness versus anger/disgust/fear/sadness from the PoFA—for example, finding that schizophrenia impairs recognition of the latter group of emotions but not of happiness—they have typically interpreted the difference as being due to valence (e.g., Henley et al., 2008; Sackeim, Gur, & Saucy, 1978; Unoka, Fogd, Füzy, & Csukly, 2011). However, the PoFA happy expressions differ from the angry/disgusted/fearful/sad ones not only in valence (positive/negative), but also in elicitation method (event-elicited/posed; Ekman, 1980). Our data indicate that the elicitation method of the PoFA stimuli strongly influences their perceived genuineness: That is, the event-elicited happy expressions were perceived as genuine, whereas the posed other expressions were mostly perceived as fake. This raises the possibility that dissociations previously attributed to valence could in fact be due to differences in perceived genuineness.

Limitations of our perceived-as-genuine and perceived-as-fake sets