Abstract

The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) responds to requests by the Department of Health for guidance on the use of selected new and established technologies in the National Health Service (NHS) in England and Wales. This paper asks whether the NICE methodological guidelines help NHS decision makers meet the objectives of maximum health improvements from NHS resources and an equitable availability of technologies. The analytical basis of the guidelines is a comparison of the costs and consequences of new and existing methods of dealing with particular conditions using the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio. We explain why information on the costs and consequences of a particular technology in isolation is insufficient to address issues of efficiency of resource use. We argue that to increase efficiency, decision makers need information on opportunity costs. We show that in the absence of such information decision makers cannot identify the efficient use of resources. Finally we argue that economics provides valid methods for identifying the maximisation of health improvements for a given allocation of resources and we describe an alternative practical approach to this problem. Drawing on the experience of Ontario, Canada where an approach similar to that proposed by NICE has been in use for almost a decade, and recent reports about the consequences of NICE decisions to date, we conclude that instead of increasing the efficiency or equity of the use of NHS resources, NICE methodological guidelines may lead to: (i) uncontrolled increases in NHS expenditures without evidence of any increase in total health improvements; (ii) increased inequities in the availability of services; and (iii) concerns about the sustainability of public funding for new technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

House of Commons’ Select Committee. Health: National Institute for Clinical Excellence. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 2002

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Technical guidance for manufactures and sponsors on making a submission to a technology appraisal. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2001

Birch S, Gafni A. On being NICE in the UK: guidelines for technology appraisal for the NHS in England and Wales. Health Econ 2002; 11: 185–91

Hutton J, Maynard A. A NICE challenge for health economics. Health Econ 2000; 9: 89–93

Sculpher H, Drummond M, O’Brien B. Effectiveness, efficiency and NICE. BMJ 2001; 322: 943–4

Cookson R, McDaid D, Maynard A. Wrong SIGN, NICE mess: is national guidance distorting allocation of resources? BMJ 2001; 323: 743–5

Weinstein HC, Stason WB. Foundation of cost-effectiveness analysis for health and medical practices. N Engl J Med 1977; 296: 716–21

Taylor R. Generating national guidance: a nice model? Paper presented at the Fifth International Conference on Strategic Issues in Health Care Management Policy, Finance and Performance in Health Care; 2002 Apr 11–13; St Andrews, Scotland

Weinstein M, Zeckhauser R. Critical ratios and efficient allocation. J Public Econ 1973; 2: 147–57

Birch S, Gafni A. Cost-effectiveness/utility analysis: do current decision rules lead us to where we want to be? J Health Econ 1992; 11: 279–96

Birch S, Gafni A. Changing the problem to fit the solution: Johannesson and Weinstein’s (mis)application of economics to real world problems. J Health Econ 1993; 12: 469–76

Laupacis A, Feeny D, Detsky A, et al. How attractive does a new technology have to be to warrant adoption and utilization?: tentative guidelines for using clinical and economic evaluations. CMAJ 1992; 146: 473–81

Gafni A, Birch S. Guidelines for the adoption of new technologies: a prescription for uncontrolled growth in expenditures and how to avoid the problem. CMAJ 1993; 148: 913–7

Laupacis A. Inclusion of drugs in provincial drug benefit programs: who is making these decisions, and are they the right ones? CMAJ 2002; 166: 44–7

Williams A. The economic role of ‘health indicators’. In: Teeling Smith G, editor. Measuring the social benefits of medicine. London: Office of Health Economics, 1983

Sendi P, Gafni A, Birsh S. Opportunity costs and uncertainty in the economic evaluation of health care interventions. Health Econ 2002; 11: 23–31

Naylor CD. Cost-effectiveness analysis: are the outputs worth the inputs? ACP Journal Club 1996; 124: A12–4

Culyer AJ. Health, economics and health economics. In: van der Gaaf J, Perlman M, editors. Health, economics and health economics. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company, 1981: 3–11

Maynard A, Sheldon T. Health economics: has it fulfilled its potential? In: Maynard A, Chalmers I, editors. Non-random reflection on health services research. London: BMJ Press, 1997

Burk K. NICE may fail to stop “postcode prescribing”, MPs told. BMJ 2002; 324: 191

Acknowledgements

No funding was received to assist in the preparation of this manuscript and the authors have no conflicts of interest directly relevant to the content of this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

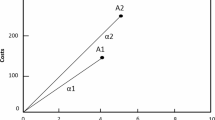

Table I describes four hypothetical different new programmes aimed at treating four different conditions. Each programme is described in terms of the additional effects and additional costs (for all patients with the disease) as compared with the current way of treating these patients together with the ICER. Suppose that the government has allocated a budget of $20 million for new programmes and has asked a committee to recommend which programmes it should pay for.

Suppose that the committee decides that $50 000 per QALY is an acceptable ‘price’ to pay for health improvements. Under this approach the committee approves only programme A. The total health improvements increase by 360 QALYs. However programme A does not use up the entire budget.The residual budget is only sufficient to fund programme D. But this programme fails to meet the acceptable ‘price’ of the committee.

Notice that although programmes B and C fail to meet the acceptable ‘price’, using the additional resources to support these two programmes would generate 388 additional QALYs, i.e. more health improvements than produced by investing resources only in drug A.

Even if the residual resources of $2 million associated with buying programme Awere to be used on programme D (there are insufficient residual resources to purchase programme B or C) the total health improvements generated from adopting programmes A and D is 380 QALYs, less than the 388 QALYs produced by programmes B and C. Irrespective of how residual resources are used, purchasing programme A does not lead to an efficient use of resources. In other words, the use of the ICER fails to maximise the health improvements from a given (additional) budget.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gafni, A., Birch, S. NICE Methodological Guidelines and Decision Making in the National Health Service in England and Wales. Pharmacoeconomics 21, 149–157 (2003). https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200321030-00001

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200321030-00001