Abstract

Eczema, frequently named atopic dermatitis, is the most frequent chronic skin disease of early childhood, with a high prevalence in industrialized countries and a relapsing-remitting course that is responsible for a serious burden on affected children and their families. Even though most facets of this disease are nowadays well known and numerous guidelines are available, some confusion still exists regarding certain aspects. First, several names have been proposed for the disorder. We suggest that the name and definition adopted by the World Allergy Organization should be used: ‘eczema,’ divided into ‘atopic,’ when an allergic sensitization can be demonstrated, and ‘non-atopic,’ in the absence of sensitization.

Several diagnostic criteria have been proposed, but at present the two most reliable are the 2003 revision by the American Academy of Dermatology of the Hanifin-Rajka criteria, and those by Williams revised in 2005. To date, 20 different clinical scores have been published to assess the severity; however, only the EASI (Eczema Area and Severity Index), the SCORAD (SCORing Atopic Dermatitis), and the POEM (Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure) seem to have been adequately validated and are recommended for use in clinical practice and trials. The diagnostic tests to identify associated allergy or sensitization include skin-prick tests, determination of the specific IgE in serum using different assays, and atopy patch tests; in the case of suspected food allergy, a food challenge may be necessary to define the diagnosis.

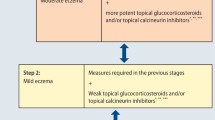

To evaluate quality of life, tools exist that allow both the child’s and family’s impairment to be considered. In addition, several algorithms exist to help decide therapy on a step-wise basis. However, such guidelines and algorithms represent only an aid to the physician and not an obligatory directive, since the ultimate judgment regarding any therapy must be performed by the physician and tailored to individual needs. A clear and validated definition of eczema control would permit better monitoring of the disease, similar to the situation with asthma in recent years. Finally, the review examines the role of special textiles in diminishing Staphylococcus aureus skin superinfection, of house dust-mite avoidance measures, and of educational programs for patients and their families, which may all help improve eczema.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

The International Study of Asthma and Allergy in Childhood (ISAAC) Steering Committee. Worldwide variation in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic eczema: ISAAC. Lancet 1998; 351: 1125–32

Asher MI, Montefort S, Björkstén B, on behalf of the ISAAC Phase Three Study Group. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC phases one and three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet 2006; 368: 733–43

Leung DYM, Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet 2003; 361: 151–60

Olesen AB, Bang K, Juul S, et al. Stable incidence of atopic dermatitis among children in Denmark during the 1990s. Acta Derm Venereol 2005; 85: 244–7

Harris JM, Williams HC, White C, et al. Early allergen exposure and atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol 2007; 156: 698–704

Illi S, von Mutius E, Laus S, et al. The natural course of atopic dermatitis from birth to age 7 years and the association with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004; 113: 925–31

Ricci G, Patrizi A, Baldi E, et al. Long-term follow-up of atopic dermatitis: retrospective analysis of related risk factors and association with concomitant allergic diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55: 765–71

Hanifin JM. Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2002; 22: 1–24

Eigenmann P, Sicherer S, Borowski T, et al. Prevalence of IgE-mediated food allergy among children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatrics 1998; 101: e8

Burks AW, James JM, Hiegel A, et al. Atopic dermatitis and food hypersensitivity reactions. J Pediatr 1998; 132: 132–6

Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol 1980; 92 Suppl.: 44–7

Wüthrich B. Atopic dermatitis flare provoked by inhalant allergens. Dermatologica 1989; 178: 51–3

Johansson SGO, Hourihane JO’B, Bousquet J, et al. A revised nomenclature for allergy: an EAACI position statement from the EAACI nomenclature task force. Allergy 2001; 56: 813–24

Johansson SGO, Bieber T, Dahl R, et al. Revised nomenclature for allergy for global use: report of the Nomenclature Review Committee of the World Allergy Organization, October 2003. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004; 113: 832–6

Novembre E, Cianferoni A, Lombardi E, et al. Natural history of ‘intrinsic’ atopic dermatitis. Allergy 2001; 56: 452–3

Wüthrich B, Schmid-Grendelmeier P. Natural history of AEDS. Allergy 2002; 57: 267–8

Wüthrich B, Schmid-Grendelmeier P. The atopic eczema/dermatitis syndrome: epidemiology, natural course, and immunology of the IgE-associated (‘extrinsic’) and the nonallergic (‘intrinsic’) AEDS. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2003; 13: 1–5

Wallach D, Taïeb A, Tilles G. Histoire de la dermatite atopique. Paris: Masson Ed, 2005

Giardina E, Sinibaldi C, Chini L, et al. Co-localization of susceptibility loci for psoriasis (PSORS4) and atopic dermatitis (ATOD2) on human chromosome 1q21. Hum Hered 2006; 61: 229–36

Marenholz I, Nickel R, Rüschendorf F, et al. Filaggrin loss-of-function mutations predispose to phenotypes involved in the atopic march. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006; 118: 866–71

Nomura T, Sandilands A, Akiyama M, et al. Unique mutations in the filaggrin gene in Japanese patients with ichthyosis vulgaris and atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 119: 434–40

Palmer CA, Ismail T, Lee SP, et al. Filaggrin null mutations are associated with increased asthma severity in children and young adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 120: 64–8

Cork MJ, Robinson DA, Vasilopoulos Y, et al. New perspectives on epidermal barrier dysfunction in atopic dermatitis: gene-environment interactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006; 118: 3–21

Hanifin JM, Lobitz Jr WC. Newer concepts of atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol 1977; 113: 663–70

Williams HC, Burney PG, Hay RJ, et al. The UK Working Party’s diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis: I. Derivation of aminimum set of discriminators for atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol 1994; 131: 383–96

Bos JD, Van Leent EJ, Sillevis Smitt JH. The millennium criteria for the diagnosis of atopic dermatitis. Exp Dermatol 1998; 4: 132–8

Einchenfield LF, Hanifin JM, Luger TA, et al. Consensus conference on pediatric atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003; 49: 1088–95

Williams HC. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 2314–24

European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis. Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: the SCORAD index. Consensus report of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatology 1993; 186: 23–31

Hanifin JM, Thurston M, Omoto M, et al. The eczema area and severity index (EASI): assessment of reliability in atopic dermatitis. EASI Evaluator Group. Exp Dermatol 2001; 10: 11–8

Charman CR, Venn AJ, Williams HC. The patient-oriented eczema measure. Arch Dermatol 2004; 140: 1513–9

Dreborg S, Frew A. Position paper: allergen standardization and skin tests. Allergy 1993; 47 Suppl. 14: 48–82

Sampson HA, Ho DG. Relationship between food-specific IgE concentrations and the risk of positive food challenges in children and adolescents. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1997; 100: 444–51

Niggemann B, Reibel S, Wahn U. The atopy patch test (APT): a useful tool for the diagnosis of food allergy in children with atopic dermatitis. Allergy 2000; 55: 281–5

Sampson HA. Update on food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004; 113: 805–19

Niggemann B, Rolinck-Werninghaus C, Mehl A, et al. Controlled oral food challenges in children–when indicated, when superfluous? Allergy 2005; 60: 865–70

Lewis-Jones MS, Finlay AY. The Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI): initial validation and practical use. Br J Dermatol 1995; 132: 942–9

Lawson V, Lewis-Jones MS, Finlay AY, et al. The family impact of childhood atopic dermatitis: Dermatitis Family Impact Questionnaire. Br J Dermatol 1998; 138: 107–13

Lewis-Jones MS, Finlay AY, Dykes PJ. The Infants’ Dermatitis Quality of Life Index. Br J Dermatol 2001; 144: 104–10

Holme SA, Man I, Sharpe JL, et al. The Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index: validation of the cartoon version. Br J Dermatol 2003; 148: 285–90

McKenna SP, Whalley D, Abigail LD, et al. International development of the Parents’ Index of Quality of Life in Atopic Dermatitis (PIQoL-AD). Qual Life Res 2005; 14: 231–41

Ellis C, Luger T, Abeck D, et al., on behalf of the ICCAD II Faculty. International Consensus Conference on Atopic Dermatitis II (ICCAD II): clinical update and current treatment strategies. Br J Dermatol 2003; 148 Suppl. 63: 3–10

Hanifin JM, Cooper KD, Ho VC, et al. Guidelines of care for atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004; 50: 391–404

Abramovits W, Goldstein AM, Stevenson LC. Changing paradigms in dermatology: topical immunomodulators within a permutational paradigm for the treatment of atopic and eczematous dermatitis. Clin Dermatol 2003; 21: 383–91

Abramovits W. A clinician paradigm in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005; 53 (1 Suppl. 1): S70–7

Eichenfield LF. Consensus guidelines in diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis. Allergy 2004; 59 Suppl. 78: 86–92

Darsow U, Lübbe J, Taïeb A, et al. Position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2005; 19: 286–95

Akdis CA, Akdis M, Bieber T, et al., on behalf of the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology/American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/PRACTALL Consensus Group. Diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in children and adults: European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology/American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/PRACTALL Consensus report. Allergy 2006; 61: 969–87

Jøhnke H, Vach W, Norberg LA, et al. A comparison between criteria for diagnosing atopic eczema in infants. Br J Dermatol 2005; 153: 352–8

Taïeb A, Boralevi F. Atopic eczema in infants. In: Ring J, Przybilla B, Ruzicka T, editors. Handbook of atopic eczema. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 2006: 45–60

Rajka G, Langeland T. Grading of the severity of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh) 1989; 144: 13–4

Emerson RM, Charman CR, Williams HC. The Nottingham Eczema Severity Score: preliminary refinement of the Rajka and Langeland grading. Br J Dermatol 2000; 142: 288–97

Kunz B, Oranje AP, Labreze L, et al. Clinical validation and guidelines for the SCORAD index: consensus report of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatology 1997; 195: 10–9

Oranje AP, Glazenburg EJ, Wolkerstorfer A, et al. Practical issues on interpretation of scoring atopic dermatitis: the SCORAD index, objective SCORAD and the three-item severity score. Br J Dermatol 2007; 157: 645–8

Berth-Jones J. Six Area, Six Sign Atopic Dermatitis (SASSAD) severity score: a simple system for monitoring disease activity in atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol 1996; 135 Suppl. 48: 25–30

Sugarman JL, Fluhr JW, Fowler AJ, et al. The objective severity assessment of atopic dermatitis score: an objective measure using permeability barrier function and stratum corneum hydration with computer-assisted estimates for extent of disease. Arch Dermatol 2003; 139: 1417–22

Eichenfield LF, Lucky AW, Boguniewicz M, et al. Safety and efficacy of pimecrolimus (ASM 981) cream 1% in the treatment of mild and moderate atopic dermatitis in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 46: 495–504

Gollnick H, Kaufmann R, Stough D, et al. Pimecrolimus cream 1% in the longterm management of adult atopic dermatitis: prevention of flare progression: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol 2008; 158: 1083–93

Charman C, Chambers C, Williams H. Measuring atopic dermatitis severity in randomized controlled trials: what exactly are we measuring? J Invest Dermatol 2003; 120: 932–41

Schmitt J, Langan S, Williams HC, on behalf of the European Dermato-Epidemiology Network. What are the best outcome measurements for atopic eczema? A systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 120: 1389–98

Sicherer SH, Sampson HA. Food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006; 117: S470–5

Ramesh S. Food allergy overview in children. Clinic Rev Allerg Immunol 2008; 34: 217–30

Bath-Hextall F, Delamere FM, Williams HC. Dietary exclusions for established atopic eczema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008 Jan 23; (1): CD005203

Ricci G, Bendandi B, Bellini F, et al. Atopic dermatitis: quality of life of young Italian children and their families and correlation with severity score. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2007; 18: 245–9

Berger TG, Duvic M, Van Voorhees AS, et al., on behalf of the American Academy of Dermatology Association Task Force. The use of topical calcineurin inhibitors in dermatology: safety concerns. Report of the American Academy of Dermatology Association Task Force. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 54: 818–23

Bieber T, Cork M, Ellis C, et al, for the Pediatric Advisory Committee of the Food and Drug Administration. Consensus statement on the safety profile of topical calcineurin inhibitors. Dermatology 2005; 211: 77–8

Fonacier L, Charlesworth EN, Spergel JM, et al. The black box warning for topical calcineurin inhibitors: looking outside the box. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2006; 97: 117–20

Spergel JM, Leung DY. Safety of topical calcineurin inhibitors in atopic dermatitis: evaluation of the evidence. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2006 Jul; 6 (4): 270–4

Fleischer Jr AB. Black box warning for topical calcineurin inhibitors and the death of common sense. Dermatol Online J 2006; 12: 2

Ricci G, Dondi A, Patrizi A. Role of topical calcineurin inhibitors on atopic dermatitis of children. Curr Med Chem 2007; 14: 1579–91

Ashcrotft DM, Chen LC, Garside R, et al. Topical pimecrolimus for eczema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; (4): CD005500

Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Global strategy for asthma management and prevention [online]. Available from URL: http://www.ginasthma.org [Accessed 2009 May 25]

Langan SM, Thomas KS, Williams HC. What is meant by a ‘flare’ in atopic dermatitis? A systematic review and proposal. Arch Dermatol 2006; 142: 1190–6

Diepgen TL, Stabler A, Hornstein OP. Textile intolerance in atopic eczema: a controlled clinical study. Z Hautkr 1990; 65: 907–10

Bendsoe N, Bjornberg A, Asnes H. Itching from wool fibres in atopic dermatitis. Contact Derm 1987; 17: 21–2

Bunikowski R, Mielke ME, Skarabis H, et al. Evidence for a disease-promoting effect of Staphylococcus aureus-derived exotoxins in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2000; 105: 814–9

Ricci G, Dondi A, Patrizi A. Staphylococcus aureus overinfection in atopic dermatitis. J Pediatr Infect Dis 2008; 3: 83–90

Gauger A, Mempel M, Schekatz A, et al. Silver-coated textiles reduce Staphylococcus aureus colonization in patients with atopic eczema. Dermatology 2003; 207: 15–21

Gettings RL, Triplett BL. A new durable antimicrobial finish for textiles. Anaheim (CA): AATCC National Technical Conference Book of Papers, 1978: 259–61

Ricci G, Patrizi A, Bendandi B, et al. Clinical effectiveness of a silk fabric in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol 2004; 150: 127–31

Ricci G, Patrizi A, Mandrioli P, et al. Evaluation of the antibacterial activity of a special silk textile in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Dermatology 2006; 213: 224–7

Wohlrab J, Jost G, Abeck D. Antiseptic efficacy of a low-dosed topical triclosan/chlorexidine combination therapy in atopic dermatitis. Skin Pharmacol Physiol 2007; 20: 71–6

Tupjer AR, De Monchy JGR, Coenraads PJ. Induction of atopic dermatitis by inhalation of house dust mite. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1996; 97: 1064–70

Sanda T, Yasue T. Effectiveness of house dust mite allergen avoidance through clean room therapy in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1991; 89: 653–7

Nishioka K, Yasueda H, Saito H. Preventive effect of bedding encasement with microfine fibers on mite sensitization. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1998; 101: 28–32

Ricci G, Patrizi A, Specchia F, et al. Mite allergen (Der p1) levels in houses of children with atopic dermatitis: the relationship with allergometric tests. Br J Dermatol 1999; 140: 651–5

Wahn U, Lau S, Bergmann R, et al. Indoor allergen exposure is a risk factor for sensitization during the first three years of life. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1997; 99: 763–9

Nickel R, Kulig M, Forster J, et al. Sensitization to hen’s egg at the age of twelve months is predictive for allergic sensitization to common indoor and outdoor allergens at the age of three years. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1997; 99: 613–7

Sasai K, Furukawa S, Muto T, et al. Early detection of specific IgE antibody against house dust mite in children at risk of allergic disease. J Pediatr 1996; 128: 834–40

Platts-Mills TAE, Vervloet D, Thomas WR, et al. Indoor allergens and asthma: report of the third international workshop. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1997; 100: S1–24

Tan BB, Weald D, Strickland I, et al. Double blind controlled trial of effect of house dust mite allergen avoidance on atopic dermatitis. Lancet 1996; 347: 15–8

Ricci G, Patrizi A, Specchia F, et al. Effect of house dust mite avoidance measures in children with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol 2000; 143: 379–84

Oosting AJ, de Bruin-Weller MS, Terreehorst I, et al. Effect of mattress encasings on atopic dermatitis outcome measures in a double-blind, placebocontrolled study: the Dutch mite avoidance study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002; 110: 500–6

Terreehorst I, Duivenvoorden HJ, Tempels-Pavlica Z, et al. The effect of encasings on quality of life in adult house dustmite allergic patients with rhinitis, asthma and/or atopic dermatitis. Allergy 2005; 60: 888–93

Bussmann C, Maintz L, Hart J, et al. Clinical improvement and immunological changes in atopic dermatitis patients undergoing subcutaneous immunotherapy with a house dustmite allergoid: a pilot study. Clin Exp Allergy 2007; 37: 1277–85

Cadario G, Galluccio AG, Pezza M, et al. Sublingual immunotherapy efficacy in patients with atopic dermatitis and house dust mites sensitivity: a prospective pilot study. Curr Med Res Opin 2007; 23: 2503–6

Stabb D, Diepgen TL, Fartasch M, et al. Age related, structured educational programmes for the management of atopic dermatitis in children and adolescents: multicentre, randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2006; 332: 933–6

Ricci G, Bendandi B, Aiazzi R, et al. Educational and medical programme for young children affected by atopic dermatitis and for their parents. Dermatol Psychosom 2004; 5: 187–92

Grillo M, Gassner L, Marshman G, et al. Pediatric atopic eczema: the impact of an educational intervention. Pediatr Dermatol 2006; 23: 428–36

Acknowledgments

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this review. The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ricci, G., Dondi, A. & Patrizi, A. Useful tools for the Management of Atopic Dermatitis. AM J Clin Dermatol 10, 287–300 (2009). https://doi.org/10.2165/11310760-000000000-00000

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/11310760-000000000-00000