Abstract

Background

Radiology serves in the diagnosis and management of many diseases. Despite its rising importance and use, radiology is not a core component of a lot of medical school curricula. This survey aims to clarify current gaps in the radiological education in Egyptian medical schools. In February–May 2021, 5318 students enrolled in Egyptian medical schools were recruited and given a 20-multiple-choice-question survey assessing their radiology knowledge, radiograph interpretation, and encountered imaging experiences. We measured the objective parameters as a percentage. We conducted descriptive analysis and used Likert scales where values were represented as numerical values. Percentages were graphed afterwards.

Results

A total of 5318 medical students in Egypt answered our survey. Gender distribution was 45% males and 54% females. The results represented all 7 class years of medical school (six academic years and a final training year). In assessing students’ knowledge of radiology, most students (75%) reported that they received ‘too little’ education, while 20% stated the amount was ‘just right’ and only 4% reported it was ‘too much.’ Sixty-two percent of students stated they were taught radiology through medical imaging lectures. Participants’ future career plans were almost equally distributed. Near half of participants (43%) have not heard about the American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria (ACR-AR), while 39% have heard about it but are not familiar with.

Conclusions

Radiology is a novel underestimated field. Therefore, medical students need more imaging exposure. To accomplish this, attention and efforts should be directed toward undergraduate radiology education to dissolve the gap between radiology and other specialties during clinical practice. A survey answered by medical students can bridge between presence of any current defect in undergraduate radiology teaching and future solutions for this topic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Medical education has been a concern to researchers worldwide. They have tried multiple ways to improve teaching methods to both students and physicians. Currently, medical education system has yielded well-trained physicians worldwide. However, due to technology advancement (which radiology mainly relies on), modifications need to be made to both undergraduate (UME) and graduate medical educations (GME) [1,2,3].

Egyptian medical education was divided into six academic years and a final training year. In their first 3 years of medical school, students establish a foundation of basic sciences (Anatomy, Physiology, Pathology) for which they build upon in the latter 3 years with clinical sciences (Internal medicine, Surgery, Pediatrics). Following these six academic years, a final training year is approached to apply the acquired clinical knowledge (as house officers) before graduation [4, 5]. This traditional educational ladder has shifted recently to a new modified one; it crafts a more integrated path between both basic and clinical sciences [4]. We included participants enrolled in both models in our survey. In the traditional older model, the first 3 academic years will be referred to as preclinical years, while the 3 subsequent years will be referred to as clinical ones.

Radiology plays a vital role in modern medicine; it helps with diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of many diseases. Unfortunately, there is a worldwide lack of undergraduate radiology education [6,7,8,9]. Some medical schools do not require radiology as a clerkship in their curriculum [10, 11]. The need for undergraduate imaging teaching has been discussed in the literature [8,9,10, 12].

Most medical students will deal with imaging, regardless to their chosen specialty. Therefore, a basic training to enhance radiology knowledge and imaging interpretation is necessary to prepare them for clinical practice. This training is important even for non-radiologists since radiology is implicated in many other specialties [13,14,15,16]. In addition, students should learn how and when to order a certain imaging study. To solve this, the American College of Radiology (ACR) has created their appropriateness criteria (ACR Appropriateness Criteria or ACR-AC); in any given clinical presentation, they have created a list of the most appropriate radiographs to order. This in turn should minimize imaging overuse and unnecessary orders [17, 18].

Like any other specialty, radiology education is a lifelong journey; it occurs at 3 levels: undergraduate (UME; medical students), graduate (GME; residency and fellowship), and continuous medical educations (CME; senior radiologists) [19, 20]. In this national study, we conduct a survey to assess current awareness and attitude toward radiology among medical students (UME) in Egypt. This could provide preliminary data on the current status of Egyptian undergraduate radiology education (Where do we stand?) and how to address potential issues (How can we start?).

Methods

This is a multicenter survey across Egyptian medical schools. It was composed by American-Board-certified radiologists with many years of experience in radiology teaching; similar surveys were used as a reference [21, 22]. The survey consisted of 20 multiple-choice questions forming a comprehensive online questionnaire to assess Egyptian medical schools radiology education. Focus was on five main categories: (1) demographic data; (2) preclinical radiology education; (3) clinical radiology education; (4) exposure to the American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria (ACR-AC); and (5) confidence in image evaluation (See Additional file 1: "Supplementary Material: Survey Questions"). At the beginning of the survey, informed consent was obtained electronically from participants that answers will be used for data analysis and research purposes.

The survey was conducted between February and May 2021. In early February, 36 student ambassadors were recruited from all over Egypt via interest emails; they represented their medical schools by circulating the survey with their colleagues using social media platforms. Each medical school had 1 to 3 ambassadors. This way, our ambassadors covered a large proportion of Egyptian medical schools (Cairo, Ain Shams, Alexandria, Al-Azhar, Benha, Zagazig, Fayyom, Menoufia, Sohag, Assiut, and Aswan). During survey timeframe, a total of 5318 responses were collected from various Egyptian medical schools. The questionnaire was designed using SurveyMonkey (SurveyMonkey Inc., San Mateo, CA, USA), and then percentages were graphed using Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington State). Demographic data focused on gender, class year of medical school, and future career plans. Questions then addressed the following: whether the first 3 academic years (preclinical years) of medical school tested diagnostic radiology; whether they received formal education in various aspects of radiology; the faculty who taught their radiology curriculum; and the teaching modalities and resources provided by their school.

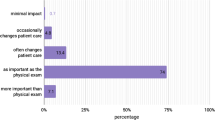

Students were then asked about their familiarity with ACR-AC and how often they use them. Other questions to assess students' confidence were in evaluating specific findings on chest radiographs and if they think it is important for interns (house officers) to interpret certain radiological studies such as bone, chest, abdominal radiographs, and head computed tomography (CT). The questionnaire also included inquiries about last 3 academic years (clinical years) of medical school, assessing the frequency the students interacted with radiologists during clinical rotations and if they encountered any radiological imaging. The survey asked about level of satisfaction regarding the amount of radiology education they received. Finally, our team of radiologists and educational specialists evaluated the questions for clarity and accuracy. Descriptive analyses were conducted through SurveyMonkey, while Likert score responses were scaled via numerical values (i.e. 1 = not important, 2 = somewhat important, 3 = moderately important, 4 = very important).

Results

Responses represented nearly most medical schools across Egypt. From 5318 participants, 54.48% (2897) were females, 45.09% (2398) were males, and 0.43% (23) preferred not to answer. Gathered data were from students in one of the 6 academic years and house officers in their final training year (Table 1). When asked about future career plans, 12.45% showed interest in radiology, while 29.9% in medicine, 25.87% in the surgical field, and 31.76% were undecided.

Radiology teaching during preclinical years

Most students (78.77%) mentioned that their first 3 years (preclinical) examinations included radiology images. Radiology training during medical school was almost equally distributed with 23.09% as a required rotation, 14.8% elective rotation, 21.44% with no radiology training, and 26.4% of students did not have any clinical encounter yet. Only 24.18% responded that radiology training was taught by radiology faculty, while 23.22% stated it was taught by non-radiologists (Fig. 1). When asked about imaging teaching method, nearly two-thirds (62.7%) mentioned it was lectures for medical imaging, while the others (30.76%) stated it was self-guided learning with images provided.

Nearly all students stated that their preclinical examinations included radiology imaging (96%). Furthermore, two-thirds of students (67%) responded that imaging was taught by radiologists. The most encountered radiology teaching methods were didactic lectures (86%) and self-guided learning (61%). Less than half (38%) responded that their schools provided students with resources to go through medical imaging on their own outside the classroom. Students were taught multiple modalities. Methods taught most frequently were X-ray, ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), with less representation for positron emission tomography (PET) and fluoroscopy (Fig. 2). Only 7.18% reported that they received formal training in radiation safety. However, 43.4% of students correctly answered a question asking about the background radiation level an X-ray can expose to a patient.

Radiology teaching during clinical years

During clinical rounds of the last 3 academic years (clinical years), only 2% of students had daily interactions with radiologists, 3% interacted few times per week, 22% interacted few times per month, 45% interacted once or twice during the year, and 27% have never had any interaction with radiologists.

During interpreting radiographs on rounds, most students (91%) discussed imaging with a non-radiologist, 84% with a resident, and only 22% with a radiologist; nine percent of students did not encounter any radiological imaging.

ACR appropriateness criteria

Nearly half (43.4%) of participants have never heard of the ACR Appropriateness Criteria (ACR-AC), and 39.2% heard about it but were not familiar with. Sixty-four percent of students never used ACR-AC. About half of students (47.8%) stated that they have not been provided with resources from their medical school to learn radiology on their own.

Imaging interpretation

Above 60% of students received formal education in detecting bone fractures (68.45%), pneumonia (62.84%), and pleural effusions (62.07%), with nearly half (45.64%) for subdural hemorrhage (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Radiology teaching to medical students has been underscored [16, 23, 24]. In the last two decades, the field of radiology has advanced tremendously, but undergraduate radiology teaching has not achieved a similar growth. Prior surveys in both the USA and the UK had shown the inadequacy of radiology teaching to medical students [8, 10]. This national survey serves as a tool to determine radiology education status in Egypt to guide solutions of any potential problems.

In our study across Egyptian medical schools, most students (75.44%) perceived the amount of teaching radiology in their curriculum as ‘too little.’ These results are similar to a recent study in the UK which showed that allocated time in teaching radiology was 0.3% of their curriculum timetable [10]. A similar trend was seen in a study in Canada where 90% of students wished to have more radiology teaching in medical school [25]. Curricula could be overcrowded and often overloaded, limiting given time for radiology teaching [9]. Given the importance of image interpretation in physicians’ daily life, there is an insisting demand for better radiology education. Moreover, there is evidence that early exposure to radiology, even in the preclinical years, has improved physical diagnosis, application of clinical anatomy, student satisfaction, and of course radiological interpretation [26,27,28]. These positive effects indicate the need for an approach to focus more on radiology in the undergraduate medical curriculum.

Almost equal percentages of our participants reported that radiologists (24.18%) or non-radiologists (23.22%) had taught them medical imaging. Our data also highlighted that teaching radiology in Egyptian medical schools varied between a required rotation (23.09%), an elective rotation (14.8%), or its complete absence (21.44%). In the UK, radiology teaching is not a standalone subject, while in most American and European medical schools, it is a discrete clinical rotation [8, 10]. In addition, radiology training in the USA has been integrated throughout preclinical disciplines (such as anatomy) and clinical rotations (such as internal medicine and surgery) [8], while in our study radiology education is primarily taught through didactic lectures. The European Society of Radiology (ESR) recommends initiatives for undergraduate radiology teaching to maximize the application of learned contents. These new approaches include the following: e-learning modules integrated into the undergraduate curriculum; flipped classroom where students actively take on a role in their learning pathways; problem-solved scenarios; simulation techniques to teach imaging reasoning and appropriateness; and finally, virtual reality (VR) that can construct an anatomical environment and different pathologies to acquire new skills [29].

The American College of Radiology (ACR) has developed annually reviewed guidelines for appropriate use of imaging techniques known as ACR Appropriateness Criteria (ACR-AC). These guidelines aim to assist referring physicians in ordering the most appropriate imaging for over 211 topics and almost 1900 clinical scenarios [30]. Unfortunately, in parallel with many US interns, almost half of our students in Egypt (43.44%) have never heard of this valuable resource [31]. Additional efforts should be made to increase awareness and utilization of the ACR-AC. This can be achieved through didactic lectures and multidisciplinary sessions—where radiology is integrated with other disciplines as surgery. Increasing accessibility to these guidelines through spreading them into trainee forums and clinical consults may be helpful as well [31]. Similarly, our data show a knowledge gap in Egyptian students regarding radiation safety. Early implementation of ACR-AC on students can help to modify imaging ordering patterns, eliminate excess radiation exposure, and avoid unnecessary costs of radiologic studies.

Our participating students represented all medical school class years (six academic with a final training one) with almost equal distribution for their future career plans (radiologist, internist, or surgeon). One limitation was that we relied only on an online survey which may not permit some students’ access. However, we believe that most medical students are familiar with digital resources. Another limitation was the participation of a small portion of medical graduates (‘Others’ in Table 1). This assessment focuses more on undergraduate population which may encourage another study in the future to evaluate this important topic from another perspective (radiology residents and faculty members).

Conclusion

Radiology is an underestimated specialty despite its integration into other specialties nowadays. In addition, undergraduate radiology education and awareness of the American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria (ACR-AC) may not be receiving the appropriate attention. We believe a national survey conducted and answered by medical students can fill the gap between presence of any weaknesses in undergraduate radiology education and creating a pathway to strengthen them.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ACR:

-

American College of Radiology

- ACR-AC:

-

American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria

- UME:

-

Undergraduate medical education

- GME:

-

Graduate medical education

- CME:

-

Continuing medical education

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- USA:

-

United States of America

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- ESR:

-

European Society of Radiology

- VR:

-

Virtual reality

References

Knebel, E., & Greiner, A. C. (Eds.). (2003). Health professions education: A bridge to quality.

Gutierrez CM, Cox SM, Dalrymple JL (2016) The revolution in medical education. Tex Med 112:58–61

Samarasekera DD, Goh PS, Lee SS, Gwee MCE (2018) The clarion call for a third wave in medical education to optimise healthcare in the twenty-first century. Med Teach 40:982–985

Abdelaziz A, Kassab SE, Abdelnasser A, Hosny S (2018) Medical education in Egypt: historical background, current status, and challenges. Heal Prof Educ 4:236–244

Abdalla ME, Suliman RA (2013) Overview of medical schools in the eastern mediterranean region of the world health organization. East Mediterr Heal J 19:1020–1025

Linaker KL (2015) Radiology undergraduate and resident curricula: a narrative review of the literature. J Chiropr Humanit 22:1–8

Corr P (2012) Using e-learning movies to teach radiology to students. Med Educ 46:1119–1120

Straus CM et al (2014) Medical student radiology education: summary and recommendations from a national survey of medical school and radiology department leadership. J Am Coll Radiol 11:606–610

Schiller PT, Phillips AW, Straus CM (2018) Radiology education in medical school and residency: the views and needs of program directors. Acad Radiol 25:1333–1343

Chew C, O’Dwyer PJ, Sandilands E (2021) Radiology for medical students: Do we teach enough? A national study. Br J Radiol 94:20201308

Poot JD, Hartman MS, Daffner RH (2012) Understanding the US medical school requirements and medical students’ attitudes about radiology rotations. Acad Radiol 19:369–373

Al Qahtani F, Abdelaziz A (2014) Integrating radiology vertically into an undergraduate medical education curriculum: a triphasic integration approach. Adv Med Educ Pract 5:185–189

Friloux L, Gunderman RB, Siddiqui AR, Heitkamp DE, Kipfer HD (2003) The vital role of radiology in the medical school curriculum. Am J Roentgenol 181:1428

Gunderman RB et al (2000) The value of good medical student teaching: increasing the number of radiology residency applicants. Acad Radiol 7:960–964

Scheiner JD, Novelline RA (2000) Radiology clerkships are necessary for teaching medical students appropriate imaging work-ups. Acad Radiol 7:40–45

Retrouvey M, Trace AP, Goodmurphy CW, Shaves S (2018) Redefining the radiology curriculum in medical school: vertical integration and global accessibility. Am J Roentgenol 210:118–122

Cascade, P. N., & Chairman, T. F. (2000). ACR Appropriateness Criteria TM Project.

Sheng AY, Castro A, Lewiss RE (2016) Awareness, utilization, and education of the ACR appropriateness criteria: a review and future directions. J Am Coll Radiol 13:131–136

Osborne M, Fields S (2014) Training physicians for the future US health care system. Futur Hosp J 1:56–61

Aschenbrener CA, Ast C, Kirch DG (2015) Graduate medical education: its role in achieving a true medical education continuum. Acad Med 90:1203–1209

Prezzia C, Vorona G, Greenspan R (2013) Fourth-year medical student opinions and basic knowledge regarding the field of radiology. Acad Radiol 20:272–283

Nyhsen CM, Steinberg LJ, O’Connell JE (2013) Undergraduate radiology teaching from the student’s perspective. Insights Imaging 4:103–109

Shepherd SM, Dudewicz DM, Hindo WA (2003) Immediate and long-term effects of a sophomore radiology elective. Acad Radiol 10:786–793

Smith EB, Sherrill GC, Lewis PJ, Faykus MW, Jordan SG (2021) Online hide and seek: allopathic US medical schools’ radiology education virtual presence. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. https://doi.org/10.1067/j.cpradiol.2021.03.005

Dmytriw AA, Mok PS, Gorelik N, Kavanaugh J, Brown P (2015) Radiology in the undergraduate medical curriculum: Too little, too late? Med Sci Educ 25:223–227

Heptonstall NB, Ali T, Mankad K (2016) Integrating radiology and anatomy teaching in medical education in the UK-the evidence, current trends, and future scope. Acad Radiol 23:521–526

Chew C, O’Dwyer PJ, Young D, Gracie JA (2020) Radiology teaching improves anatomy scores for medical students. Br J Radiol 93:20200463

Murphy KP et al (2015) Medical student perceptions of radiology use in anatomy teaching. Anat Sci Educ 8:510–517

Oleaga L et al (2019) ESR statement on new approaches to undergraduate teaching in radiology. Insights Imaging 10:1–6

American College of Radiology (ACR). (2021). ACR Appropriateness Criteria®. Retrieved from https://www.acr.org/Clinical-Resources/ACR-Appropriateness-Criteria.

Saha A, Roland RA, Hartman MS, Daffner RH (2013) Radiology medical student education: an outcome-based survey of PGY-1 residents. Acad Radiol 20:284–289

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors reviewed and provided input before and during the drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Supplementary Material: Survey Questions.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Badawy, M., Rohren, S., Elhatw, A. et al. Teaching radiology in Egyptian medical schools: Where do we stand and how can we start?. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med 53, 15 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43055-021-00684-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43055-021-00684-x