Abstract

Building a relationship with the maritime supply chain partners is considered imperative for organisations to survive and remain competitive. Yet, several studies that examined the maritime supply chain have not adequately explored nor assessed the relationship constructs that impacts maritime supply chain performance. This study intends to fill this gap and ascertain the influence that certain relationship elements have on the maritime supply chain performance. The study is solely a desk research. After providing a general overview of maritime supply chain and its structure, relationship marketing paradigm and relationship constructs, this study examines the influence that the identified relationship constructs (i.e. trust, commitment and satisfaction) has on supply chain performance. The study asserts that the present of the identified relationship constructs (i.e. trust, commitment and satisfaction) among supply chain partners will influence supply chain performance positively. Hence, building a successful long-term relationship among maritime supply chain partners requires an understanding of these key relationship constructs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Maritime SC is structured by an integration of maritime services and transshipment functions to maritime distribution functions (Frankel 1999). Likewise, Chryssolouris et al. (2004) stated that maritime SC involve different interrelated partners, with each performing distribution or manufacturing operations and activities. These views suggest that maritime SC consider the interests of all parties involved in the development of the chain. Lam (2011, p. 366) stated further that a maritime SC is “the connected series of activities pertaining to shipping services which is concerned with planning, coordinating and controlling containerized cargoes from the point of origin to the point of destination”. This is consistent with Polatidis et al. (2018) assertion that maritime SC comprise interconnected and globally distributed organizations involving different entities. Arguably, maritime SC is complex as it involves several types of interactions among SC partners, which require effective relationship management (Song et al. 2016).

Furthermore, Oliveira et al. (2016, p. 166) defined supply chain (SC) “as an aggregate set of value chains linked by inter-organizational relationships, both upstream and downstream of the leader company in order to deal with all the flows involved (cash, material, goods, and information), from the first supplier’s supplier to the last customer of the end customer, as well as the reverse flow of products and returnable and/or disposable products, generating value for the end consumer and for SC stakeholders”, while supply chain management (SCM) is the coordination of the chain of events associated with the movement of goods from raw materials to the ultimate customer (Mentzer et al. 2001). These views suggest that the SC represent a network of relationships formed to ensure that efficient and effective products and services are delivered to the end customer within the chain (Fawcett and Magnan 2004). Hence, the success of a firm is dependent on its ability to integrate its intra and inter-firm processes and coordinate the intricate network of business relationships among supply chain member (Yuen and Thai 2017).

Globalization and competitive pressure have given rise to dynamic and complex SC (Christopher et al. 2006; Creazza et al. 2010). Hence, scholar and researchers alike have laid emphasis on the need for fundamental changes within the maritime SC relationships (Berle et al. 2011). This could be constructed to the assertion that a business ultimate success and competitiveness depends on its ability to coordinate and integrate the various business networks within the SC (Lambert and Cooper 2000; Wilding and Humphries 2006; Carbone and Gouvernal 2007; Song and Panayides 2008; Efendigil et al. 2008; Yuen and Thai 2017). It is therefore imperative for firms to have a supply chain that will foster efficient and effective optimization of goods, services and information (Disney and Towill 2003; Childerhouse and Towill 2003; Bhatnagar and Teo 2009).

Lam and Van De Voorde (2011, p. 705) argued that fostering relationship within the supply chain is imperative because “competition in the business world nowadays is largely between supply chains, rather than between individual players only”. This is consistent with Lam (2011, p. 373) assertion that fostering “integration in maritime supply chains can bind the partners in a vertically-collaborative relationship that enables the organisations to accomplish their goals collectively and efficiently”. Berle et al. (2011) added that developing and maintaining of a good supply chain relationship will foster the development of effective and efficient capabilities for the supply chain partners. Likewise, Panayides and Song (2013) asserted that it is imperative for maritime businesses to build close collaborative relationships across the supply chains. Gunasekaran et al. (2015) concluded that relationship, which is developed over a period is essential for supply chain partners in attaining collaboration effort towards higher quality, lower cost, reduce risks, greater product innovation and enhance market value.

Although many studies have reported the direct impact of relationship on maritime SC, there is a lack of research evident exploring and assessing relationship constructs as it affects the maritime SC. The primary aim of this paper is therefore to develop a new conceptual framework linking maritime SC and relationship constructs by reviewing the relevant literature on maritime sector, maritime SC, relationship marketing and relationship constructs.

Literature review

Maritime SC and its structure

Maritime SC remains a leading service sector for promoting global and intercontinental trade. Banomyong (2005) referred to Maritime SC as an essential system that links the globe together. This is because the maritime SC plays a vital role as an intermediary and in transportation to facilitate trade flow in intercontinental and global SC (Wong et al. 2011). This is consistent with Cheng et al. (2015) assertion that the maritime activities and operations contribute about 70% of international trade by value and approximately 80% by volume globally. Hence, it is an essential trade life-line for manufacturing companies globally (Jasmi and Fernando 2018). Obviously, intercontinental trade relies heavily on maritime transportations to carry various cargoes for catalyzing global import-export trade.

Lam (2011, p. 366), defined a maritime SC as “the connected series of activities pertaining to shipping services which is concerned with planning, coordinating and controlling containerised cargoes from the point of origin to the point of destination”. This view suggests that adding value to goods and services transported remains a key focus for maritime SC while providing time and place utility (Lam 2015). Arguably, adding value through the transportation of goods and service remains the core purpose of maritime SC. This is in line with Jasmi and Fernando (2018) conclusion that maritime SC is the movement of cargoes and related support service involving two substantial locations using land transportations and maritime.

Frankel (1999) noted that maritime SC structure focuses on the integration of transshipment functions and maritime services to maritime distribution functions. This suggests that there exists different players and interactions within the maritime SC (Song et al. 2016). This is consistent with Polatidis et al. (2018) assertion that the maritime SC structure comprises of interconnected and globally distributed organisations. Arguably, the maritime sector could be categorised as complex. Hence, there is a need to foster appropriate relationship and management among these complex SC partners, port authorities, shipping organizations and import-export firms.

Why foster relationship among maritime SC partners?

Increased competition has helped accelerate transport and transport services efficiency in meeting customers’ requirements (Pando et al. 2005). The OECD (2011) added that competition in the maritime sector is considered essential in fostering effective functioning of the ports and port services in contributing respectively to the global economy and determining a product final price. These views are in line with Jasmi and Fernando (2018) assertion that the maritime SC organisations are traditionally subjected to competitive forces. Yet, Lazakis et al. (2016) argued that competition in the maritime sector has given rise to more pretentious and compound structures.

Contrary to these views, Stank et al. (2001) stated that relationship among SC partners fosters collaborative decision-making, which involves collective and joint ownership of decisions. This is consistent with Lam (2013) assertion that developing and maintaining supply chain relationships result in making decisions that involves active participation of all partners, which maximize supply chain profitability. Tseng and Liao (2015) added that relationship avails partners with information that will enhance in building and maintaining the SC. Likewise, De Martino and Morvillo (2008) emphasised that interdependencies and reciprocal benefits among SC partners will only be achieved through relationship. This is consistent with the argument that relationship among SC partners result in a long-term relationship as opposed to contractual relationships, which help improve quality services and reduce complexity (Woo et al. 2013).

Effective relationship management among SC partners improve capacity (Bichou and Gray 2004) and increase firm performance (Sheu et al. 2006). This is consistent with Fawcett and Magnan (2004) argument that relationship among SC partners facilitate the delivery of best products and services to the market, and efficient and effective value delivery to supply chain end customer. Richey Jr et al. (2010) and Germain and Iyer (2006) added that integral relationship within the SC promotes organisational performance. Likewise, Heaver (2011), and Acosta et al. (2007) asserted that relationship eases the accessibility and increased safety and improved efficient operations. Hence, More and Basu (2013) concluded that closer relationships with SC partners’ avails firms the opportunity to increase business agility and effectively cost cutting. These views suggest that SC partners recognize business synergy to compete effectively with other supply chains, and how such collaboration would enhance performance by working together (Yu et al. 2013).

Scholars and researchers have also argued that forming relationship with different SC partners encourages collective responsibility for sustainable development (Stank et al. 2001). Likewise, relationships among SC partners increases environmental protection performance (Sarkis 2001). These views are consistent with Gunasekaran et al. (2008) argument that relationship promotes the concept of circular economy through continuous improvement, total quality management and responsive SC. Song et al. (2016) concluded that cooperation should be encouraged among maritime SC players to accommodate the structural changes in the sector. Exploring and developing long-term relationships among SC partners, which is a key concept to the relationship marketing paradigm becomes important to the continuity and survival of partners within the maritime sector.

Relationship marketing paradigm

There is no generally acceptable definition of relationship, which emerges from the field of relationship marketing (Buttle 1996). This is because the concept definition varies in different disciplines. Broom et al. (2000) within the public relations discipline referred to a relationship as a series comprising interaction, exchange, transaction, and linkage between the partners involved. Hence, effective relationship theory should encourage collaboration because “effectively managing organizational-public relationships around common interests and shared goals, over time, results in mutual understanding and benefit for interacting organizations and publics” (Ledingham 2003, p. 190). Likewise, from a communication perspective, Coombs (2001) defined relationship as a link existing among partners with a mutual purpose over a period. Hence, relationship is termed a two-way route in which partners are aware of each other and their respective interaction. Furthermore, Håkansson and Snehota (1995), p. 25) within the social psychology discipline termed relationship as “a mutually oriented interaction between two reciprocally committed parties”, while Hallahan (2004, p. 775) from an organisation standpoint concluded that relationship involves “routinized, sustained patterns of behaviour by individuals related to their involvement with an organisation”. Despite the difference in opinion of these scholars, they have all perceived relationship as a means of interaction that emerges among partners.

Relationship marketing on the other hand has been referred to as “establishing, maintaining, and enhancing relationships with customers and other partners, at a profit, so that the objectives of the parties involved are met. This is achieved by a mutual exchange and fulfilment of promises”. This is consistent with Kotler and Armstrong (2010) view that relationship marketing is the process that avails relationship partners obtain what they desire by identifying and exchanging value with one another. Arguably, effective relationship management is essential for any business success (Smith 1998a; Wilson 1995). Researchers within the field of marketing have claimed that keeping an existing relationship is easier and cheaper than attracting a new relationship (Athanasopoulou 2009). Hence, organisations should strive to develop and maintain a long-term relationship with their respective partners. This is consistent with scholars’ argument that organisations should engage and/or involve their business partners to build mutually beneficial relationships (Jahansoozi 2007) as partners are bound to maintain a closely related relationship (Vieira et al. 2008). It is worth stating that the intention to use marketing research is to help identify and understand relationship variables that could guide the development of a bespoke model focused on facilitating maritime SC relationships.

Methodology

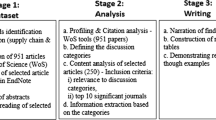

The purpose of this paper is to synthesize maritime SC and relationship marketing literature to develop a conceptual framework that will foster a successful long-term relationship among maritime supply chain partners. This section therefore explains how the conceptual framework was developed step by step. Also, presents how the literature review and scoping review were performed and the conceptual framework developed, as shown in Fig. 1.

This study conducted a scoping review, which aims to map the literature on a research area or topic and provide an opportunity to identify gaps in the research and develop conceptual model that will inform research, policymaking and practice (Daudt et al. 2013). This is consistent with Davis et al. (2009, p. 1386) assertion that “scoping involves the synthesis and analysis of a wide range of research and non-research material to provide greater conceptual clarity about a specific topic or field of evidence”. Authors such as Dijkers (2015) and Arksey and O’Malley (2005) argued that scoping review is different from other types of review in that they address broader topics and are less likely to focus on a specific research question. Hence, the scoping review was conducted to identify relationship quality constructs that have been evaluated and consistently mentioned in the literature by following the five steps framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley.

Identifying the research question

As with other types of review, it is imperative to identify a research question(s), which guides the way that the search strategies are built (Arksey and O’Malley 2005). Hence, the overarching research question guiding the search is “What are the main constructs that defines the quality of a relationship”.

Identifying relevant studies

Arksey and O’Malley (2005) asserted that being able to identify appropriate and relevant studies and reviews suitable for answering the stated research question is essential. We conducted an electronic search of relevant articles on relationship quality dimensions through Web of Science and Scopus. The databases were selected to cover a broad range of disciplines and considered comprehensive. There was no limit placed on the date of publication, focus or type of relationship, and type or subject on the database search. Relationship quality, relationship quality construct, relationship construct, relationship dimension, relationship determinants, relationship precursors, and building blocks of relationship are the phrases and/or terms used as the search query to meet the specific needs of the database considered.

Study selection

A two-stage selection process was used in identifying the appropriate and relevance studies. First, one of the authors checked the journal articles generated through the search phrases and/or terms for relevance and any duplicate records since it is impossible to include every single journal articles. Thereafter, the second author carried out an abstract check of all the remaining articles resulting in the selection of a total of 62 journal articles considered appropriate for the study.

Charting the data

This stage involves the extraction of data and synthesising same to provide narratives of the selected studies. We recorded information such as the name of the authors, year of publication, methods, relationship focus/type, and research contributions of the studies considered appropriate. Together, these data formed the basis of the analysis.

Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

The data gathered through charting were compiled in a single excel spreadsheet analysis because it presents a tabular form of different measurement used in evaluating and assessing selected studies (Osobajo and Moore 2017) as shown in Table 1.

Scoping review results and discussion

The initial search, which was conducted in August 2019 yielded 1059 likely relevant studies. After initial screening of the potential studies for deduplication, only 851 studies qualified for the next round of screening. The next round of screening involves screening the 851 studies based on identified inclusion criteria. At the end of this round, the authors are left with only 196 studies, which are further subjected to full text-text review. Five studies could not be accessed, while 129 studies are considered irrelevant to this study. Hence, only 62 studies were included in the scoping review and analysis as shown in Fig. 2.

An overview of the scoping review and analysis carried out suggested that the first study that focused on ascertaining relationship quality dimensions was conducted in 1987 by Dwyer and Oh. Since then, the concept has received continuous attention from various researchers in different industries. Out of the 62 studies reviewed, forty-seven studies (76%) took on board the questionnaires, five studies (8%) utilised interviews, only one study (2%) took on board case study, while nine studies (14%) employed mixed method of data collection. Of the nine studies, seven studies utilised questionnaires & interviews, one study respectively employed questionnaires, interviews & case study, and questionnaires & focused group. In summary, most of the studies reviewed suggested that researchers and scholars alike have used the questionnaire as the main method of collecting quantitative data, while qualitative and mixed methods have been accorded little attention. This could be attributed to Vieira et al.’s (2008) argument that questionnaires as a means of collecting quantitative data provides scholars and researchers alike with more generalisable data.

In addition, the scoping review revealed that the constructs of relationship quality have been explored in different industries and sectors such as manufacturing, service, hospitality, distribution, financial and retail. Likewise, researchers and scholars alike have explored different types of relationships such as business to business (i.e. a wholesaler and a retailer or a manufacturer and wholesaler), business to customer, customer to business, and interpersonal relationships in the process of contributing to the ongoing discussions on relationship quality constructs.

Furthermore, scholars within the relationship marketing field of study have identified various constructs upon which the quality of a relationship is built. The difference in opinion with respect to these constructs could be linked to the perspective, context and research settings in which various studies have been carried out (Vieira et al. 2008). These constructs have also been referred to as precursors, determinants, dimensions or building blocks of relationship (Athanasopoulou 2009; Vieira et al. 2008). However, the focus of this study will be on trust, satisfaction and commitment, which have been consistently mentioned and evaluated in the literature. In addition, these three variables form an area of convergence for studies on relationship because they have been validated in different contexts (Osobajo and Moore 2017).

Development of a conceptual framework

The primary aim of this paper is to extend the body of knowledge by establishing the link between relationship constructs and maritime SC performance. Hence, the relationship between maritime SC and trust, satisfaction and commitment, which represent an area of convergence for relationship quality constructs will be explored further.

Trust

Trust is considered imperative in developing and maintaining relationships. Trust is defined as a belief (Kumar et al. 1995; Morgan and Hunt 1994), or expectation of relationship partners (Dwyer et al. 1987). These views suggest that trust could be termed a behavioural intention (Moorman et al. 1992; Tian et al. 2008). This is because partners in a relationship are at risk of one another choices because of uncertainty within the relationship. This is consistent with Hewett and Bearden (2001) claim that trust is an essential variable that supports promises-making and promises-keeping. Hence, it has significant influence on relationship success (Akrout 2015).

Trust is also defined as the perceived benevolence and credibility among relationship partners (Ganesan 1994). This view suggests that the genuine interest of relationship partners is important for trust to exist. This is consistent with Morgan and Hunt (1994, p. 23) claim that trust is perceived to exist “when one party has confidence in an exchange partner’s reliability and integrity”. This view further suggests that trust also focus on the assessment of relationship partners’ personality traits. Arguably, trust among partners is important in developing and maintaining a successful relationship. This is consistent with Smyth et al. (2010) assertion that trust among relationship partners is important in dealing with unplanned or unforeseen events. Halinen (2012) concluded that trust influences interactions among relationship partners, while giving room for open and honest interactions. Relationship building among SC partners involves partners trusting one another by understanding each other’s problems and performing effectively.

H1: This study posits it that the existence of trust among maritime partners will positively influence SC performance.

Satisfaction

Roberts et al. (2003, p. 175) defined satisfaction as “the customer’s cognitive and affective evaluation based on their personal experience across all service episodes within the relationship”. This view suggests that satisfaction entails the assessment or appraisal of a relationship by partners based on their respective experience and dealings with one another. Likewise, Wilson (1995) referred to satisfaction as a measure of outcome or performance expected of a relationship partner. Meaning that satisfaction represent a positive emotional and/ or rational state resulting from a relationship evaluation. This further suggests that satisfaction evaluates relationship partners’ past and current dealings and interactions to influence future development and expectations (Roberts et al. 2003).

Satisfaction is further defined by Anderson and Narus (1990) as the fulfilment shared by partners in a relationship due to achieving desired outcomes. This is consistent with scholars’ assertion that satisfaction measures the extent in which relationship partners expected performance is met taking into consideration transactions that transpired between the partners (Wilson 1995). Thus, these views suggest that the achievement of a partner’s goals and objectives with the help of another partner will results in satisfaction (Anderson and Narus 1990; Kumar et al. 1995). Therefore, one could conclude that parties to a relationship have an obligation to contribute towards the achievement of one anothers goals and objectives as opposed to competing with one another.

H2: This study posits it that shared fulfilment of maritime partners needs and expectations will positively influence SC performance.

Commitment

Commitment is “an enduring desire to maintain a valued relationship” (Moorman et al. 1992, p. 316). Likewise, Morgan and Hunt (1994, p. 23) defined commitment as “the belief that an ongoing relationship with another is so important as to warrant maximum efforts at maintaining it”. These views suggest that relationship partners desire a stable relationship and are willing to make sacrifices to maintain a stable relationship. This is in line with Chen and Paulraj (2004) assertion that commitment facilitates SC partners to integrate with their major customers’ business processes and goals. Kumar et al. (1995) claimed that commitment represent partners’ intention to continue in a relationship. Parsons (2002, p. 7) added that “commitment among partners is essential for each party achieving its goals and maintaining relationships”. This is in line with Roberts et al. (2003) argument that commitment is important in solving relationship-inherent problems and developing a long-term relationship among partners. These definitions suggest that commitment develops over time and that relationship partners have a desire to maintain the relationship, thus implying a long-term orientation towards relationship continuity. Arguably, commitment is an essential variable for a successful long-term relationship (Morgan and Hunt 1994). Relationship building among SC partners involves partners continued desire to commit to the relationship.

H3: This study posits it that maritime partners continued desire to commit to the relationship building will positively influence SC performance.Figure 3 presents the proposed framework developed in this paper.

Managerial implication and conclusion

Although the different stakeholders within the maritime SC continues to develop effective and efficient means of working successful with one another, there is still a lack of research evident exploring and assessing relationship constructs as it affects the maritime SC performance. This study therefore makes both academic and practical contributions to the ongoing discussions on fostering relationship within the maritime SC. This study has proposed a conceptual framework within this paper linking relationship constructs (i.e. trust, satisfaction and commitment) to maritime SC performance. Building trust among SC partners is essential because it influences open and honest interactions among relationship partners. Also, fostering and helping one another towards the achievement of goals and objectives can be instrumental in breaking the barrier of competition among SC partners. Likewise, committing and supporting in the achievement of partner’s goals and objectives can help build a long-term relationship.

This paper offers the following contribution. First, this paper fills the gap in research by developing a conceptual framework of relationship constructs with maritime SC performance. While many studies have reported the direct impact of relationship on maritime SC, there is a lack of research evident exploring and assessing relationship constructs as it affects the maritime SC performance. Hence, building a successful long-term relationship among maritime SC partners requires an understanding of the key relationship constructs. Secondly, over thirty relationship constructs were identified through extensive literature review. However, the paper focused on trust, satisfaction and commitment, which have been consistently mentioned, evaluated and have formed an area of convergence for studies on relationship because they have been validated in different contexts.

Despite the contributions stated above, the following limitations applies to the paper. First, no empirical attempt was carried out to validate the proposed conceptual framework. Second, only three of the identified relationship constructs were considered within the proposed conceptual framework. Hence, future conceptual studies should consider how other relationship constructs such as communication can impact maritime SC performance. Likewise, future empirical studies could employ either qualitative, quantitative or mixed method to validate the proposed conceptual framework.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Acosta M, Coronado D, Mar Cerban M (2007) Port competitiveness in container traffic from an internal point of view: the experience of the port of Algeciras Bay. Marit Policy Manag 34(5):501–520

Akrout H (2015) A process perspective on trust in buyer–supplier relationships.“calculus” an intrinsic component of trust evolution. Eur Bus Rev 27(1):17–33

Anderson JC, Narus JA (1990) A model of distributor firm and manufacturer firm working partnerships. J Mark 54(1):42–58

Arksey H, O’Malley L (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 8(1):19–32

Athanasopoulou P (2009) Relationship quality: a critical literature review and research agenda. Eur J Mark 43(5/6):583–610

Atrek B, Marcone MR, Gregori GL, Temperini V, Moscatelli L (2014) Relationship quality in supply chain management: A dyad perspective. Ege Acad Rev 14(3)

Baker TL, Simpson PM, Siguaw JA (1999) The impact of suppliers’ perceptions of reseller market orientation on key relationship constructs. J Acad Mark Sci 27(1):50–57

Banomyong R (2005) The impact of port and trade security initiatives on maritime supply-chain management. Marit Policy Manag 32(1):3–13

Barry JM, Doney PM (2011) Cross-cultural examination of relationship quality. J Glob Mark 24(4):305–323

Beatson A, Lings I, Gudergan S (2008) Employee behaviour and relationship quality: Impact on customers. Serv Ind J 28(2):211–223

Bejou D, Wray B, Ingram TN (1996) Determinants of relationship quality: An artificial neural network analysis. J Bus Res 36(2):137–143

Bennett R, Barkensjo A (2005) Relationship quality, relationship marketing, and client perceptions of the levels of service quality of charitable organisations. Int J Serv Ind Manag 16(1):81–106

Berle Ø, Asbjørnslett BE, Rice JB (2011) Formal vulnerability assessment of a maritime transportation system. Reliab Eng Syst Saf 96(6):696–705

Bhatnagar R, Teo CC (2009) Role of logistics in enhancing competitive advantage: a value chain framework for global supply chains. Int J Phys Distrib Logist Manag 39(3):202–226

Bichou K, Gray R (2004) A logistics and supply chain management approach to port performance measurement. Marit Policy Manag 31(1):47–67

Boles JS, Johnson JT, Barksdale HC (2000) How salespeople build quality relationships:: A replication and extension. J Bus Res 48(1):75–81

Bowen JT, Shoemaker S (1998) Loyalty: A strategic commitment. Cornell Hotel Restaur Admin Q 39(1):12–25

Broom G, Casey S, Ritchey J (2000) Toward a concept and theory of organization–public relationships: an update. In: Ledingham JA, Bruning SD (eds) Public relations as relationship management: a relational approach to public relations. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc, Mahwah, pp 3–22

Buttle F (1996) Relationship marketing. Relationship Marketing: Theory and Practice, Paul Chapman Publishing, London, pp 1–16

Carbone V, Gouvernal E (2007) Supply chain and supply chain management: appropriate concepts for maritime studies. In: Wang J, Olivier D, Notteboom T, Slack B (eds) Ports, cities and global supply chains. Ashgate, England, pp 11–26

Carr CL (2006) Reciprocity: The golden rule of IS-user service relationship quality and cooperation. Commun ACM 49(6):77–83

Chang HH, Ku PW (2009) Implementation of relationship quality for CRM performance: Acquisition of BPR and organisational learning. Total Qual Manage 20(3):327–348

Chen IJ, Paulraj A (2004) Understanding supply chain management: critical research and a theoretical framework. Int J Prod Res 42(1):131–163

Cheng TCE, Farahani RZ, Lai KH, Sarkis J (2015) Sustainability in maritime supply chains: challenges and opportunities for theory and practice. Transportation research Part E Logistics and transportation review

Childerhouse P, Towill D (2003) Simplified material flow holds the key to supply chain integration. Omega 31(1):17–27

Christopher M, Peck H, Towill D (2006) A taxonomy for selecting global supply chain strategies. Int J Logist Manag 2(2):277–287

Chryssolouris G, Makris S, Xanthakis V, Mourtzis D (2004) Towards the internet-based supply chain management for the ship repair industry. Int J Comput Integr Manuf 17(1):45–57

Clark M, Vorhies D, Bentley J (2011) Relationship quality in the pharmaceutical industry: An empirical analysis. J Med Mark 11(2):144–155

Coombs WT (2001) Interpersonal communication and public relations. In: RL Heath Handbook of public relations. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, pp 105–114

Creazza A, Dallari F, Melacini M (2010) Evaluating logistics network configurations for a global supply chain. Supply Chain Manag An Int J 15(2):54–164

Crosby LA, Evans KR, Cowles D (1990) Relationship quality in services selling: An interpersonal influence perspective. J Mark 54(3):68–81

Daudt HM, van Mossel C, Scott SJ (2013) Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med Res Methodol 13(1):48

Davis K, Drey N, Gould D (2009) What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. Int J Nurs Stud 46(10):1386–1400

De Martino M, Morvillo A (2008) Activities, resources and inter-organizational relationships: key factors in port competitiveness. Marit Policy Manag 35(6):571–589

De Ruyter K, Moorman L, Lemmink J (2001) Antecedents of commitment and trust in customer–supplier relationships in high technology markets. Ind Mark Manag 30(3):271–286

Dijkers M (2015) What is a scoping review? In: KT Update 4(1) Available via. https://ktdrr.org/products/update/v4n1/dijkers_ktupdate_v4n1_12-15.pdf. Accessed 18 Jan 2020

Disney SM, Towill DR (2003) The effect of vendor managed inventory (VMI) dynamics on the bullwhip effect in supply chains. Int J Prod Econ 85(2):199–215

Doney PM, Cannon JP (1997) An examination of the nature of trust in buyer-seller relationships. J Mark 61(12):35–51

Dorsch MJ, Swanson SR, Kelley SW (1998) The role of relationship quality in the stratification of vendors as perceived by customers. J Acad Mark Sci 26(2):128–142

Dwyer FR, Oh S (1987) Output sector munificence effects on the internal political economy of marketing channels. J Mark Res 24(4):347–358

Dwyer FR, Schurr PH, Oh S (1987) Developing buyer-seller relationships. J Mark 51(2):11–27

Efendigil T, Önüt S, Kongar E (2008) A holistic approach for selecting a third-party reverse logistics provider in the presence of vagueness. Comput Ind Eng 54(2):269–287

Farrelly FJ, Quester PG (2005) Examining important relationship quality constructs of the focal sponsorship exchange. Ind Mark Manag 34(3):211–219

Fawcett SE, Magnan GM (2004) Ten guiding principles for high-impact SCM. Bus Horiz 47(5):67–74

Frankel EG (1999) The economics of total trans-ocean supply chain management. Int J Marit Econ 1(1):61–69

Friman M, Gärling T, Millett B, Mattsson J, Johnston R (2002) An analysis of international business-to-business relationships based on the Commitment–Trust theory. Ind Mark Manag 31(5):403–409

Fynes B, de Burca S, Marshall D (2004) Environmental uncertainty, supply chain relationship quality and performance. J Purch Supply Manage 10(4‐5):179‐90

Ganesan S (1994) Determinants of long-term orientation in buyer-seller relationships. J Mark 58(2):1–19

Garbarino E, Johnson MS (1999) The different roles of satisfaction, trust, and commitment in customer relationships. J Mark 63(2):70–87

Gentzler AL, Oberhauser AM, Westerman D, Nadorff DK (2011) College students’ use of electronic communication with parents: Links to loneliness, attachment, and relationship quality. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 14(1-2):71–74

Germain R, Iyer KN (2006) The interaction of internal and downstream integration and its association with performance. J Bus Logist 27(2):29–52

Goodman LE, Dion PA (2001) The determinants of commitment in the distributor–manufacturer relationship. Ind Mark Manag 30(3):287–300

Gunasekaran A, Lai KH, Cheng TCE (2008) Responsive supply chain: a competitive strategy in the network economy. Omega 36(4):549–564

Gunasekaran A, Subramanian N, Rahman S (2015) Green supply chain collaboration and incentives: current trends and future directions, Transportation research part E: logistics and Transportation Review, p 74

Håkansson H, Snehota I (1995) Developing relationships in business networks. Routledge, London

Halinen A (2012) Relationship marketing in professional services: a study of agency-client dynamics in the advertising sector. Routledge, London

Hallahan K (2004) Community as a foundation for public relations theory and practice. Ann Int Commun Assoc 28(1):233–279

Han S, Wilson DT, Dant SP (1993) Buyer-supplier relationships today. Ind Mark Manag 22(4):331–338

Heaver TD (2011) Coordinating in multi-actor logistics operations: challenges at the port Interface. In: Hall P, McCalla RJ, Comtois C, Slack B (eds) Integrating seaports and trade corridors, pp 155–170

Hennig-Thurau T (2000) Relationship quality and customer retention through strategic communication of customer skills. J Mark Manag 16(1-3):55–79

Henning-Thurau T, Gwinner KP, Gremler DD (2002) Understanding relationship marketing outcomes: an integration of relational benefits and relationship quality. J Serv Res 4(3):230–247

Hewett K, Bearden WO (2001) Dependence, trust, and relational behavior on the part of foreign subsidiary marketing operations: implications for managing global marketing operations. J Mark 65(4):51–66

Hewett K, Money RB, Sharma S (2002) An exploration of the moderating role of buyer corporate culture in industrial buyer-seller relationships. J Acad Mark Sci 30(3):229–239

Huntley JK (2006) Conceptualization and measurement of relationship quality: Linking relationship quality to actual sales and recommendation intention. Ind Mark Manag 35(6):703–714

Jahansoozi J (2007) Organization–public relationships: an exploration of the sundre petroleum operators group. Public Relat Rev 33(4):398–406

Jap SD, Manolis C, Weitz BA (1999) Relationship quality and buyer–seller interactions in channels of distribution. J Bus Res 46(3):303–313

Jasmi MFA, Fernando Y (2018) Drivers of maritime green supply chain management. Sustain Cities Soc 43:366–383

Johnson JL (1999) Strategic integration in industrial distribution channels: Managing the interfirm relationship as a strategic asset. J Acad Mark Sci 27(1):4–18

Johnson JL, Sakano T, Cote JA, Onzo N (1993) The exercise of interfirm power and its repercussions in US-Japanese channel relationships. J Mark 57(2):1–10

Keating B, Rugimbana R, Quazi A (2003) Differentiating between service quality and relationship quality in cyberspace. Manag Serv Qual Int J 13(3):217–232

Keating BW, Alpert F, Kriz A, Quazi A (2011) Mediating role of relationship quality in online services. J Comput Inf Syst 52(2):33–41

Kotler P, Armstrong G (2010) Principles of marketing. Pearson education

Kumar N, Scheer LK, Steenkamp JBE (1995) The effects of supplier fairness on vulnerable resellers. J Mark Res 32(1):54–65

Lagace RR, Dahlstrom R, Gassenheimer JB (1991) The relevance of ethical salesperson behavior on relationship quality: The pharmaceutical industry. J Pers Sell Sales Manag 11(4):39–47

Lages C, Lages CR, Lages LF (2005) The RELQUAL scale: A measure of relationship quality in export market ventures. J Bus Res 58(8):1040–1048

Lai IKW (2014) The role of service quality, perceived value, and relationship quality in enhancing customer loyalty in the travel agency sector. J Travel Tour Mark 31(3):417–442

Lam JSL (2011) Patterns of maritime supply chains: slot capacity analysis. J Transp Geogr 19(2):366–374

Lam JSL (2013) Benefits and barriers of supply chain integration: empirical analysis of liner shipping. Int J Shipping Transport Logistics 5(1):13–30

Lam JSL (2015) Designing a sustainable maritime supply chain: a hybrid QFD–ANP approach. Transport Res Part E Logistics Transport Rev 78:70–81

Lam JSL, Van De Voorde E (2011) Scenario analysis for supply chain integration in container shipping. Marit Policy Manag 38:705–725

Lambert DM, Cooper MC (2000) Issues in supply chain management. Ind Mark Manag 29:65–83

Lang B, Colgate M (2003) Relationship quality, on-line banking and the information technology gap. Int J Bank Mark 21(1):29–37

Lazakis I, Dikis K, Michala AL (2016) Condition monitoring for enhanced inspection, maintenance and decision making in ship operations. Proceedings of PRADS2016, Copenhagen, Denmark 4–8 September 2016

Ledingham JA (2003) Explicating relationship management as a general theory of public relations. J Public Relat Res 15(2):181–198

Leonidou CN, Leonidou LC, Coudounaris DN, Hultman M (2013) Value differences as determinants of importers’ perceptions of exporters’ unethical behavior: The impact on relationship quality and performance. Int Bus Rev 22(1):156–173

Leonidou LC, Barnes BR, Talias MA (2006) Exporter–importer relationship quality: The inhibiting role of uncertainty, distance, and conflict. Ind Mark Manag 35(5):576–588

Leuthesser L (1997) Supplier relational behavior: An empirical assessment. Ind Mark Manag 26(3):245–254

Lin S (2013) The influence of relational selling behavior on relationship quality: The moderating effect of perceived price and customers’ relationship proneness. J Relationship Mark 12(3):204–222

Menon A, Bharadwaj SG, Howell R (1996) The quality and effectiveness of marketing strategy: Effects of functional and dysfunctional conflict in intraorganizational relationships. J Acad Mark Sci 24(4):299–313

Mentzer JT, DeWitt W, Keebler JS, Min S, Nix NW, Smith CD, Zacharia ZG (2001) Defining supply chain management. J Bus Logist 22(2):1–25

Moorman C, Zaltman G, Deshpande R (1992) Relationships between providers and users of market research: the dynamics of trust within and between organizations. J Mark Res 29(3):314

More D, Basu P (2013) Challenges of supply chain finance: a detailed study and a hierarchical model based on the experiences of an Indian firm. Bus Process Manag J 19(4):624–647

Morgan RM, Hunt SD (1994) The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J Mark 58(3):20–38

Morry MM, Kito M (2009) Relational-interdependent self-construal as a predictor of relationship quality: The mediating roles of one's own behaviors and perceptions of the fulfillment of friendship functions. J Soc Psychol 149(3):305–322

Naudé P, Buttle F (2000) Assessing relationship quality. Ind Mark Manag 29(4):351–361

OECD (2011) Competition in ports and port services. Available via DIALOG. http://www.oecd.org/regreform/sectors/48837794.pdf. Accessed 15 Jan 2020

Oliveira JB, Lima RS, Montevechi JAB (2016) Perspectives and relationships in supply chain simulation: a systematic literature review. Simul Model Pract Theory 62:166–191

Osobajo OA, Moore D (2017) Methodological choices in relationship quality (RQ) research 1987 to 2015: a systematic literature review. J Relationship Mark 16(1):40–81

Panayides PM, Song DW (2013) Maritime logistics as an emerging discipline. Marit Policy Manag 40(3):295–308

Pando J, Araujo A, Javier Maqueda F (2005) Marketing management at the world's major ports. Marit Policy Manag 32(2):67–87

Parsons AL (2002) What determines buyer-seller relationship quality? An investigation from the buyer’s perspective. J Supply Chain Manag 38(1):4–12

Polatidis N, Pavlidis M, Mouratidis H (2018) Cyber-attack path discovery in a dynamic supply chain maritime risk management system. Comput Stand Interfaces 56:74–82

Rafiq M, Fulford H, Lu X (2013) Building customer loyalty in online retailing: The role of relationship quality. J Mark Manag 29(3-4):494–517

Ramaseshan B, Yip LS, Pae JH (2006) Power, satisfaction, and relationship commitment in chinese store–tenant relationship and their impact on performance. J Retail 82(1):63–70

Richey RG Jr, Roath AS, Whipple JM, Fawcett SE (2010) Exploring a governance theory of supply chain management: barriers and facilitators to integration. J Bus Logist 31(1):237–256

Roberts K, Varki S, Brodie R (2003) Measuring the quality of relationships in consumer services: an empirical study. Eur J Mark 37(1/2):169–196

Sanzo MJ, Santos ML, Vázquez R, Álvarez LI (2003) The effect of market orientation on buyer–seller relationship satisfaction. Ind Mark Manag 32(4):327–345

Sarkis J (2001) Manufacturing’s role in corporate environmental sustainability - concerns for the new millennium. Int J Oper Prod Manag 21:666–686

Selnes F (1998) Antecedents and consequences of trust and satisfaction in buyer-seller relationships. Eur J Mark 32(3/4):305–322

Sheu C, Yen H, Chae B (2006) Determinants of supplier-retailer collaboration: evidence from an international study. Int J Oper Prod Manag 26(1):24–49

Smith B (1998a) Buyer-seller relationships: bonds, relationship management, and sex-type. Can J Adm Sci/Rev Can Scie Adm 15(1):76–92

Smith JB (1998b) Buyer–seller relationships: Similarity, relationship management, and quality. Psychol Mark 15(1):3–21

Smyth H, Gustafsson M, Ganskau E (2010) The value of trust in project business. Int J Proj Manag 28(2):117–129

Song DW, Panayides PM (2008) Global supply chain and port/terminal: integration and competitiveness. Marit Policy Manag 35(1):73–87

Song L, Yang D, Chin ATH, Zhang G, He Z, Guan W, Mao B (2016) A game-theoretical approach for modeling competitions in a maritime supply chain. Marit Policy Manag 43(8):976–991

Stank TP, Keller SB, Daugherty PJ (2001) Supply chain collaboration and logistical service performance. J Bus Logist 22(1):29–48

Tian Y, Lai F, Daniel F (2008) An examination of the nature of trust in logistics outsourcing relationship: empirical evidence from China. Ind Manag Data Syst 108(3):346–367

Tseng PH, Liao CH (2015) Supply chain integration, information technology, market orientation and firm performance in container shipping firms. Int J Logist Manag 26(1):82–106

Ulaga W, Eggert A (2006) Value-based differentiation in business relationships: Gaining and sustaining key supplier status. J Mark 70(1):119–136

Van Bruggen GH, Kacker M, Nieuwlaat C (2005) The impact of channel function performance on buyer–seller relationships in marketing channels. Int J Res Mark 22(2):141–158

Venetis KA, Ghauri PN (2004) Service quality and customer retention: Building long-term relationships. Eur J Mark 38(11/12):1577–1598

Vesel P, Zabkar V (2010) Comprehension of relationship quality in the retail environment. Manag Serv Qual Int J 20(3):213–235

Vieira AL, Winklhofer H, Ennew CT (2008) Relationship quality: a literature review and research agenda. J Cust Behav 7(4):269–291

Walter A, Müller TA, Helfert G, Ritter T (2003) Functions of industrial supplier relationships and their impact on relationship quality. Ind Mark Manag 32(2):159–169

Wilding R, Humphries AS (2006) Understanding collaborative supply chain relationships through the application of the Williamson organisational failure framework. Int J Phys Distrib Logist Manag 36(4):309–329

Wilson DT (1995) An integrated model of buyer-seller relationships. J Acad Mark Sci 23(4):335–345

Wong CY, Boon-Itt S, Wong CW (2011) The contingency effects of environmental uncertainty on the relationship between supply chain integration and operational performance. J Oper Manag 29(6):604–615

Woo GK, Cha Y (2002) Antecedents and consequences of relationship quality in hotel industry. Int J Hosp Manage 21(4):321‐38

Woo K, Ennew CT (2004) Business-to-business relationship quality: An IMP interaction based conceptualization and measurement. Eur J Mark 38(9/10):1252–1271

Woo SH, Pettit SJ, Beresford AK (2013) An assessment of the integration of seaports into supply chains using a structural equation model. Supply Chain Manag Int J 18(3):235–252

Wray B, Palmer A, Bejou D (1994) Using neural network analysis to evaluate buyer-seller relationships. Eur J Mark 28(10):32–48

Ying-Ping Y (2013) The Impact of Relationship Quality on Increased Electric Cooperative Relationships. Int J Electron Commerce Stud 42:239–262

Yu W, Jacobs MA, Salisbury WD, Enns H (2013) The effects of supply chain integration on customer satisfaction and financial performance: an organizational learning perspective. Int J Prod Econ 146(1):346–358

Yuen KF, Thai V (2017) Barriers to supply chain integration in the maritime logistics industry. Marit Econ Logistics 19(3):551–572

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Authors have not received any funding for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have contributed to the writing of the paper. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Osobajo, O.A., Koliousis, I. & McLaughlin, H. Making sense of maritime supply chain: a relationship marketing approach. J. shipp. trd. 6, 1 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41072-020-00081-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41072-020-00081-z