Abstract

Background

Forest structural and compositional variability is of fundamental importance for forest ecosystem functioning and species diversity. The purpose of this research was to examine how human impact has affected the compositional-structural diversity of mature pine-dominated boreal forest in boreal Fennoscandia. For this a new approach was used, based on the classification of tree sizes by the diameter at breast height (dbh) and tree species, resulting in a new variable, the diametric-species, the variation of which describes the compositional-structural diversity of the forest. This variable was used to compare the structural-compositional diversity among three forest classes with different degree of human influence, using rarefaction as the main tool of analysis, complemented by analyses based on common diversity indices.

Results

The results showed that the near-natural forest was the most diverse and the managed forest the least diverse. On the other hand, the diversity of near-natural and selectively logged forests were similar, suggesting that selectively logged forests are equal to the natural forest in their compositional-structural diversity. The analysis solely on tree species showed no significant differences among the forest classes of different human impact. The Shannon diversity index showed no significant difference between the forest classes for the diametric-species and tree species classifications only, but the Simpson index signaled a slight difference between the selectively logged and managed forest classes for the diametric-species classification. Furthermore, the Sorensen index detected a difference among forest classes in the diametric-species classification.

Conclusions

Forest utilization had an adverse impact on forest compositional-structural diversity of mature Scots pine forests. The analysis also shows that the novel approach based on diametric-species classification could be a useful tool for forest diversity analysis and comparison, especially in species-poor forests such as the boreal forest.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Forest structure and composition are essential ecosystem characteristics, because they regulate tree growth and mortality patterns, availability of resources and, habitat conditions for all forest organisms (Lindenmayer et al. 2012, 2014; Pommerening 2002, 2006; von Gadow et al. 2012). Forest structure and composition can affect the probability and spread of forest disturbances (Kuuluvainen 2002). Variation in tree sizes and tree species composition strongly contribute to the overall species diversity, because diverse micro- and macrofauna depend on different canopy layers of the forest and large old trees for shelter, nesting and food (Spies 1998; Perry et al. 2008).

Forest structure also includes deadwood, which is a significant component of forest structural diversity (Sturtevant et al. 1997; Siitonen et al. 2000). Deadwood is important for ecosystem functioning as it regulates carbon and nutrient cycling, and water availability (Graham and Cromack 1982; Karjalainen and Kuuluvainen 2002), it is also essential for forest biodiversity because it provides habitat and resources for various kinds of animals, plants and decomposers that are important for forest ecosystem functioning (Linder 1998; Brassard and Chen 2006).

Tree species composition is a key characteristic of forest ecosystems (Lindenmayer and Franklin 2002). Tree species diversity contributes positively to productivity, provides habitats and resources to the forest species, and increases forest resilience to disturbances (Hooper and Vitousek 1997; Peterson et al. 1998; Lindenmayer and Franklin 2002). The decline in tree species richness can have an adverse impact on the levels of ecosystem functions (Naeem et al. 1999; Perry et al. 2008). Although boreal forests are characterized by lower tree species richness than temperate and tropical forests, boreal forest structure and dynamics can exhibit great diversity and complexity (Lähde et al. 1999; Ylläsjärvi and Kuuluvainen 2009; Kuuluvainen and Aakala 2011). Moreover, the low number of tree species with diverging ecological characteristics suggests that the presence or absence of even a single tree species may have a considerable impact on total species diversity of the forest.

In boreal forests, human forest utilization has generally had a negative impact on forest diversity (Paillet et al. 2009). In northern Europe, forest management has been more intensive and affected the ecosystem perhaps more than anywhere in the boreal zone. This is because forest management, which is based on clear-cutting, tends to simplify forest composition and structure by removing undesirable species, suppressing fires, and by maintaining even-aged single species stands to enhance wood production (Christensen and Emborg 1996). These practices have led to a continuous decline in the number of old trees and dead wood (Siitonen 2001; Nordlind and Östlund 2003), and the practical disappearance of uneven-aged, structurally complex forests from managed forest landscapes (Kuuluvainen and Gauthier 2018).

The purpose of this research was to examine whether human utilization has impacted compositional-structural diversity of mature pine-dominated boreal forests in Fennoscandia. For this, a new approach was used, based on the classification of trees by their diameter class and species, resulting in a variable called diametric-species. Using this variable, a comparative analysis was carried out using rarefaction curve analysis and complemented by analyses based on diversity indices.

Methods

Study regions

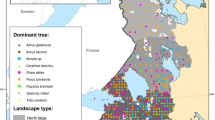

The forests in this research are located in three different regions of Fennoscandia. Häme (Pirkanmaa region) in southwestern Finland, Kuhmo (Kainuu region) in northeastern Finland, and Vienansalo (Russian Karelia) (Fig. 1).

The forests share similar characteristics in their soil, forest site type, species composition, and climatic conditions. Table 1 shows that Kuhmo and Vienansalo regions have almost identical climatic conditions. Although Häme has a slightly higher mean temperature, mean effective temperature sum and longer growing seasons, all three areas are located within the mid-Boreal vegetation zone and present similar growing conditions (Rouvinen and Kuuluvainen 2005).

The forest in all the study regions is mainly pine-dominated, with spruce and birch as part of their tree species composition, and with aspen and willow as minor species. Overall, the species composition was representative of natural forests in Fennoscandia (Axelsson and Östlund 2000; Kuuluvainen 2002). The most common and predominant forest site types were Vaccinium-Myrtillus Type (VMT) and Empetrum-Vaccinium Type (EVT). These forest site types are considered medium fertile and mesic (VMT) and poor and sub-dry (EVT) (Cajander 1926; Pyykkö 1996; Korhonen et al. 2000; Rouvinen et al. 2002a) and are usually dominated by pine trees.

The bedrock in Häme is formed mostly by granodiorite and quartz, granite, metabasalt, greenstone and amphibolite gneisses, while in the Kuhmo region a granite vein gneiss is the main component of its bedrock (National board of survey geographical society of Finland 1990), and the bedrock in Vienansalo is formed by an amphibole and biotite gneisses (Gorkovets et al. 2000). Moreover, in all the areas the topsoil covering the bedrock consists of peat deposits and ground moraines (Gorkovets et al. 2000; National board of survey geographical society of Finland 1990).

History of forest utilization of the study regions

To understand the state of these forests it is important to know the history of activities that took place in these regions. Although these regions were settled permanently at different periods of time: Häme in the mid-sixteenth century, Kuhmo in the seventeenth century, and Vienansalo in the mid-eighteenth century, they went through similar utilization stages until the early twentieth century.

Since the establishment of early settlements in the mid-sixteenth century, Häme was subject to slash and burn cultivation practices until the twentieth century. Furthermore, during the eighteenth century intensive tar extraction and burning practices were carried out in the region, and the selective logging of the forest started, which intensified during the 19th and mid-twentieth century as a result of the increase in population density of the area and the growing forestry industry in southern Finland (Lilja and Kuuluvainen 2005). Currently, many of these forests have become managed production forests, by the use of different silvicultural treatments like thinning and the removal of understory spruce trees (Rouvinen and Kuuluvainen 2005).

As in Häme, Kuhmo was the subject of slash and burn cultivation, tar production, and selective logging became an important source of livelihood for the region in the mid-nineteenth century. These practices continued for a long period until the twentieth century (Wallenius et al. 2002).

In Vienansalo, slash and burn cultivation was also carried out, as well as tar burning for domestic purposes (Rouvinen et al. 2002b). There is evidence of selective logging in the area between the 19th and 20th centuries, but the intensity of the logging was low and exclusive to Pine trees (Karjalainen and Kuuluvainen 2002). The fire regime of Vienansalo forests was the same as the ones found in eastern Finland because of the human activities that took place in the area (Kuuluvainen et al. 2002; Wallenius et al. 2004). These forests are considered to be in a more natural conservation state than the forests in Finnish Karelia (Jantunen et al. 2010).

Although Russian Karelia forests show the least amount of forest harvesting activities compared to Finnish forests (Saarinen et al. 2001), all the study areas present similar historical forest utilization backgrounds, and they only differ in the duration and intensity of human intervention.

Sampling and measurements

The sampling of these regions was carried out in three different fieldwork seasons. The first took place in Kuhmo in 1997, the second in 1998 in Vienansalo, and finally in 1999 in Häme. The aim was to collect data from three forest classes with different degrees of human impact (Lilja and Kuuluvainen 2005). These impacts were described by Lommi et al. (2009) and were classified as 1) near-natural stands; 2) selectively logged stands (selective logging was carried out in the early twentieth century, but no other treatments had been performed); 3) managed stands (stands silviculturally treated).

The stands in Kuhmo and Häme were selected from the stand data files of The Finnish Forest and Park Service (Metsahallitus) and The Finnish Forest Research Institute (LUKE), taking into consideration the following criteria: a) Pine dominated forests by volume, b) dominant Pines of at least 90 years old, and c) stand area of at least 3 ha (Rouvinen and Kuuluvainen 2005). The stands in Vienansalo were selected based on the following criteria: a) the area is remote to minimize potential human influence, b) the landscape is typical of the region, and c) there is water access to the area from the local village of Venehjärvi (Kuuluvainen et al. 2002).

A total of 116 sample plots were established in the study areas: 57 in Häme, 32 in Kuhmo, and 27 in Vienansalo. All the sampling plots were rectangular of 20 m × 100 m (0.2 ha) in size. In Häme and Kuhmo the sampling plots were randomized while making sure their location was at least 30 m from the edge of the forest area to avoid the edge effect (Lilja and Kuuluvainen 2005). In Vienansalo the sampling plots were selected randomly from 6 lines running in an east to a west direction within the study area. These lines were 1000 m apart from each other, and the plots were considered if they landed on firm land and within a relatively homogeneous forest patch (Karjalainen and Kuuluvainen 2002).

Out of the 116 sampling plots, 22 were classified as near-natural, 40 as selectively logged, and 54 as managed forests. Furthermore, 32,875 trees were measured: 7527 from the near-natural, 13,169 from the selectively logged, and 12,179 from the Managed forests.

Diametric distributions

The diametric class distributions were similar in the near-natural and selectively logged forests (Kuuluvainen et al. 2002; Rouvinen and Kuuluvainen 2005). They showed a descending or J-shaped behavior, agreeing with the behavior of an uneven-aged self-regenerating forest, in which the recruitment and mortality are in balanced, and small trees are most abundant (Felfili 1997). On the other hand, the managed forest exhibited a bimodal or rotated-sigmoid form. This behavior agrees with forests that have presented a moderate to severe disturbance or intervention (Lianjun Zhang et al. 2001) (Fig. 2).

Data analysis

The data collected contains information about the different characteristic of the forest, but for this research purpose, only tree species and the diameter at breast height (dbh) were used. The tree species found and their coding is shown in Table 2.

Each tree in the three forest classes was classified by species and diametric class, using 5 cm interval groups. By doing this, a new variable unit was created, called the diametric-species. The full classification with the 160 classes is shown in Table 3. Henceforth this new category will be referred to as diametric-species.

The diversity of diametric-species were analyzed using rarefaction curves because they account for sampling biases and adjust for the differences in the number of individuals and samples collected (Gotelli 2001; Gotelli and Colwell 2011). Rarefaction curves can compare two separate communities of different sizes and number of individuals or species by the interpolation or extrapolation of their curves (Simberloff 1972; Tipper 1979). Because of the difference in the number of diametric-species in the forest classes, the extrapolation was used to estimate the richness and completeness of the samples, by visualizing the asymptote of the cumulative curves (Chao and Jost 2012; Gotelli and Chao 2013).

The rarefaction curves were calculated using the sample-based Bernoulli product model described by Colwell et al. (2012) and the 95% low and high bound confidence intervals were also calculated for each curve. The formula used to calculate the rarefaction curve was:

And the extrapolation was calculated using the formula:

where Ssample(t) is the expected number of species (diametric-species in our case), Ssample(T + t′) is the estimated number of species extrapolated, t is the random set of sampling units, T is the total number of sampling units, t′ is the additional extrapolated sampling units, S is the total number of species in the assemblage, Sobs is the total number of species observed in the sample, i is the species, and θi is the detection probability of each species in the assemblage. To avoid any biases due to differences in sample density, the results of the sample-based rarefaction analysis were plotted against individual abundance as suggested by Gotelli and Colwell (2001).

The non-parametric Chao index was used to determine the lower bound of species richness by estimating the minimum number of species expected from an incidence data (Chao and Chiu 2016). The index takes into consideration the number of uniques and duplicates to determine the minimum number of total species in a community (Gotelli and Chao 2013).

The sample-based Chao2 index was used to determine the minimum species richness and it was only calculated for the diametric-species data because the number of species in the original data is known. The Formula as described by Gotelli and Ellison (2013):

Where S(obs) is the observed number of species, R is the number of samples in the data, q1 is the number of uniques (species that only appear in one sample) and q2 the number of duplicates (species that appear exactly in two samples).

The Shannon-Wiener, reciprocal Simpson, and Sorensen index were used in this research to complement the rarefaction diversity analyze. They were selected based on their ability to estimate alpha and beta diversity, and their use as common indices in biology, ecology, and diversity studies.

The Shannon-Wiener index (H) and the reciprocal Simpson index (D′) were calculated using the following formula:

where S is the number of species in the assemblage, and pi is the proportion of individuals that belong to the species i.

The Sorensen index was calculated using the formula:

where a is the number of species common to both samples, b the number of species unique to the first sample and c the number of species unique to the second sample.

The data was analyzed using a free to use software called EstimateS 9.1.0 (Colwell 2003). The software was used to calculate the rarefaction curves and their confidence intervals, as well as the Chao2 index. As a result of the small sample size of the near-natural and selectively logged forest, their curves were extrapolated to be matched with the managed forest larger sample size. The software randomized the data samples 100 times and calculated the average values to create the curves.

The rarefaction analysis, as well as all the diversity indices, were calculated for the diametric-species dataset and the original data containing only the tree species for comparison (Table 3).

Results

The results of the rarefaction analysis of only tree species show similar behaviors among all three forest classes (Fig. 3). The curves start with a first rapid rise, followed by a slow and steady increase until they approach the asymptote. The near-natural forest reached the asymptote at a sampling area of 4 ha, the selectively logged forest at 7.4 ha and managed forest at 10 ha. Although the forest classes reach the asymptote at different sampling area values, there are no significant differences in their curves’ behavior. Furthermore, the near-natural and selectively logged forest confidence intervals were contained within the confidence intervals of the managed forest through the entirety of their trajectory.

The rarefaction curves based on the tree diametric-species, in contrast to the curves of the sole tree species data, present different behaviors for each forest class (Fig. 4). For the near-natural forest, the rarefaction curve shows the steepest initial rise and it reaches the highest level of diametric-species (70.33) among all the three forest classes. The near-natural forest curve seems to keep rising with the increase of sampling area and it appears that the curve is far from reaching an asymptotic state. The selectively logged forest curve presents also a first steep rise but does not reach as high as the near-natural forest curve (65.15). Additionally, the selectively logged forest curve seems like it is approaching the asymptote. The managed forest, when compared to the near-natural and selectively logged forest, presents a more regular and less steep curve increase and it contains the lowest number of diametric-species (55). To compare the diametric-species in the three forest classes, the near-natural and selectively logged forests curves were extrapolated at 4.4 and 8 ha respectively to match the managed forest larger sample size.

Diametric-species rarefaction curves. a Diametric-species Rarefaction curves (solid line) and their confidence intervals of the forest classes (near-natural, selectively logged and managed forest) by sample area. The dashed line represents the extrapolation of the curves. b Rarefaction curves corrected by individual abundance

The near-natural forest’s confidence interval superimposes that of selectively logged forest throughout its entire trajectory (Fig. 4). Moreover, the near-natural and managed forests confidence intervals slightly overlap through the curves trajectory. The overlap of the near-natural and managed forest confidence intervals could be attributed to the similarities in tree species composition.

The minimum number of diametric-species estimated were: 70.59 for the near-natural forest, 65.39 for the selectively logged Forest, and 64.16 for the Managed forest, but the estimation curve of the Chao2 index (Fig. 5) shows that among the three forest classes, only the selectively logged forest reached a stable point at around 4 ha. The managed and near-natural forest curves do not stabilize and keep rising with the increase in the sampling area, suggesting the estimated minimum number of species for the near-natural and managed forest could be higher because some rare diametric-species combinations have not been registered.

The results of the Shannon index show similar values among the three forest classes for the tree species and the diametric-species classifications. The results show values between 2.9 and 2.91 for the diametric species and a value of 3.97 for all the forest classes of the tree species classification. The reciprocal Simpson index shows values between 10.4 and 12.96 for the diametric-species classification and 53.70 to 53.79 for just the tree species. The values show a difference between the managed and selectively logged forest for the diametric-species classification, but because of the near-natural forest small sample size, it was not possible to determine a significant statistical difference with the other forest classes. On the other hand, the tree species classification values for all forest classes show no significant difference (Table 4).

The Sorensen similarity index shows a difference between the forest classes of the diametric-species classification. The results ranged from 0.85 to 0.91 (Table 5). While, the values for the tree species classification were 1 for all the forest classes, meaning a total (100%) similarity between the forest classes.

Discussion

The rarefaction diversity analysis based solely on tree species did not find a diversity difference among forest age classes with different degree of human influence. This may be due to the low number of tree species in the studied boreal forests. On the other hand, when both tree size structure and species composition are considered as diametric-species, the rarefaction analysis shows a significant diversity difference among forest classes. This can be understood in the light of the findings showing that natural boreal forests are characterized by considerable and complex structural and compositional diversity (e.g. Ylläsjärvi and Kuuluvainen 2009).

The diametric-species based rarefaction analysis indicates that near-natural forests have a higher compositional-structural diversity than any other forest class. The results show a noticeable difference between diametric-species diversity of the near-natural and managed forest, suggesting that forest management had an adverse effect on forest compositional-structural diversity. These differences are the result of forest management practices that reduce the range of the tree diameter distribution by removing large trees for commercial purposes. This can be observed in the managed forest diameter distribution, where no tree individuals over 48 cm in diameter were found. In contrast, the largest tree in the near-natural forest had a diameter of 71 cm. The absence of large trees in the managed forest resulted in a lower number of diametric-species, when compared to the selectively logged and semi-natural forests. This lack of large trees in the managed forest contributes to more homogeneous forest structure, which can result in lower overall diversity of species and ecosystem functions, when compared to a natural forest (Bunnell and Huggard 1999; Lindenmayer et al. 2012, 2014; Gauthier et al. 2015). These impacts are also attributed to the suppression of small-scale disturbances that control the boreal forest dynamics, particularly important in pine-dominated forests (Kuuluvainen and Aakala 2011).

The rarefaction analysis shows a similar diametric-species diversity in the near-natural and selectively logged forest. This is supported by Lilja and Kuuluvainen (2005) who concluded that the selectively logged forest has recovered close to a natural state because the activities in the forest had occurred a long time ago and the low number of individuals removed. Alternatively, it is also possible that the near-natural forest had an undetected higher degree of human intervention (Rouvinen et al. 2002b). The similarities between the near-natural and the selectively logged forest could be relevant from a nature conservation point of view. The selectively logged forest could be considered as a potential future protected area or as a buffer zone if it is located in the vicinity of an already established protected forest.

The Chao2 index values of the near-natural forest show a considerably higher number of estimated diametric-species compared to the other forest classes, which supports the rarefaction curve findings that the near-natural forest is the most compositional-structural diverse forest class. The index curve also shows that more samples are needed to accurately determine the minimum expected number of diametric-species of the near-natural forest. The Chao2 index curve of the selectively logged forest show an accurate measurement of the minimum expected number of diametric-species and suggests the curve has reached the asymptote, this is determined by the distance between the observed richness and the Chao index estimation. (Gotelli and Ellison 2013). The Chao2 index curves also show that rare diametric-species combinations are still present in the managed forest and more samples would be needed to register them all, suggesting the managed forest could have a higher number of minimum diametric-species.

The Shannon index shows no significant difference in diversity among the three forest classes, whether the diametric-species or the original tree species data was used. The reciprocal Simpson index shows no significant difference among forest classes in the tree species classification, but found a slight difference between the managed and selectively logged forest in the diametric-species classification. It was not possible to determine if there was a statistical difference between the near-natural forest and the other forest classes because of its small sample size. These results contrast the rarefaction findings and might be the result of the indices susceptibility to evenness (Pielou 1966; Pitkänen 1998; Gotelli 2001; Colwell 2009).

The Sorensen index failed to detect a difference within forest classes in the tree species classification, but found a considerable difference between the near-natural and managed forest classes in the diametric-species classification. Furthermore, this index also shows a high similarity between the near-natural and selectively logged forest supporting the rarefaction analysis findings.

The sample size of the near-natural forest was a limiting factor in the analysis which prevented a further extrapolation of the rarefaction curve because of the method used only reliably extrapolated values up to two times the sample size (Chao and Chiu 2016). The sample size also influences the confidence intervals width because the distance between the lower and upper bounds increase the further the extrapolation moves from the reference sample (Jiroutek et al. 2003; Colwell et al. 2012). Furthermore, a near-natural forest’s larger sample size would help to visualize the curve’s asymptote and determine the completeness of the data, which in turn would give us a better understanding of the real diversity of this forest class (Chao and Jost 2012).

Conclusions

We carried out forest compositional-structural diversity analysis based on a novel diametric-species classification approach and using rarefaction analysis. Our results from mature pine forest with varying degree of human impact showed that the near-natural forest was the most diverse and the managed forest the least diverse. This indicates that forest utilization has had an adverse impact on forest compositional-structural diversity in mature Scots pine forests. On the other hand, the diversity patterns of near-natural and selectively logged forest were similar, suggesting that selectively logged forests are similar to natural forest in their compositional-structural diversity.

We conclude that the diametric-species classification, combined with the rarefaction analysis, appears to be a useful approach for quantifying and comparing forest structural and compositional diversity, especially in species-poor forests such as the boreal forest. Thus, this classification could be useful in nature conservation applications such as in assessing the level of forest naturalness and conservation potential.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the University of Helsinki boreal forest dynamics and biodiversity research group but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the University of Helsinki boreal forest dynamics and biodiversity research group.

References

Axelsson A, Östlund L (2000) Retrospective gap analysis in a Swedish boreal forest landscape using historical data. Forest Ecol Manag 147:109–122

Brassard BW, Chen HYH (2006) Stand structural dynamics of north American boreal forests. Crit Rev Plant Sci 25:115–137

Bunnell F, Huggard D (1999) Biodiversity across spatial and temporal scales: problems and opportunities. Forest Ecol Manag 115:112–126

Cajander AK (1926) The theory of forest types. Acta Forestalia Fennica 29:108

Chao A, Chiu C-H (2016) Species richness: estimation and comparison. Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference online. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118445112.stat03432.pub2

Chao A, Jost L (2012) Coverage-based rarefaction and extrapolation: standardizing samples by completeness rather than size. Ecology 93(12):2533–2547

Christensen M, Emborg J (1996) Biodiversity in natural versus managed forest in Denmark. Forest Ecol Manag 85:47–51

Colwell R (2003) EstimateS 910 user’s guide. http://viceroy.eeb.uconn.edu/estimates/. Accessed 18 May 2019

Colwell R (2009) Biodiversity: concepts, patterns, and measurement. Princeton Guide Ecol 3(1):257–263

Colwell R, Chao A, Gotelli N, Lin S-Y, Mao CX, Chazdon R, Longino J (2012) Models and estimators linking individual-based and sample-based rarefaction, extrapolation and comparison of assemblages. J Plant Ecol 5(1):3–21

Felfili J (1997) Diameter and height distributions in a gallery forest tree community and some of its main species in central Brazil over a six-year period (1985–1991). Rev Bras Bot 20(2):155–162

Gauthier S, Bernier P, Kuuluvainen T, Shvidenko A, Schepaschenko D (2015) Boreal forest health and global change. Science 349(6250):819–822

Gorkovets VY, Rayevskaya MB, Lukashov AD (2000) The geology of the proposed Kalevala, Tuuhjärvi, Koitajoki and Tolvajärvi national parks. In: Heikkilä R, Heikkilä H (eds) Biodiversity of old-growth forests and its conservation in northwestern Russia. North Ostrobothnia Regional Environment Centre. Regional Environmental Publications, vol 158, pp 159–172

Gotelli N (2001) Research frontiers in null model analysis. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 10(4):337–343

Gotelli N, Chao A (2013) Measuring and estimating species richness, species diversity, and biotic similarity from sampling data. In: Levin SA (ed) Encyclopedia of Biodiversity, vol 5, 2nd edn. Elsevier Inc., Amsterdam, pp 195–211

Gotelli N, Colwell R (2001) Quantifying biodiversity: procedures and pitfalls in the measurement and comparison of species richness. Ecol Lett 4:379–391

Gotelli N, Colwell R (2011) Estimating species richness. In: Magurran AE, McGill BJ (eds) Frontiers in measuring biodiversity. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 39–54

Gotelli N, Ellison A (2013) A primer of ecological statistics, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 449–482

Graham R, Cromack K (1982) Mass, nutrient content, and decay rate of dead boles in rain forests of Olympic National Park. Can J For Res 12:511–521

Hooper D, Vitousek P (1997) The effects of plant composition and diversity on ecosystem processes. Science 277:1302–1305

Jantunen J, Saarinen K, Saarnio S, Marttila O (2010) Stand structure in pine, spruce and deciduous forests: a comparison between Finnish and Russian Karelia. Scand J Forest Res 17(1):53–61

Jiroutek M, Muller K, Kupper L, Stewart P (2003) A new method for choosing sample size for confidence interval-based inferences. Biometrics 59(3):580–590

Karjalainen L, Kuuluvainen T (2002) Amount and diversity of coarse woody debris within a boreal forest landscape dominated by Pinus sylvestris in Vienansalo wilderness, eastern Fennoscandia. Silva Fenn 36(1):147–167

Korhonen KT, Tomppo E, Henttonen H, Ihalainen A, Tonteri T, Tuomainen T (2000) Pirkanmaan metsäkeskuksen alueen metsävarat 1965–1999. Metsätieteen Aikakauskirja 4B/2000:661–739

Kuuluvainen T (2002) Natural variability of forests as a reference for restoring and managing biological diversity in boreal Fennoscandia. Silva Fenn 36(1):97–125

Kuuluvainen T, Aakala T (2011) Natural forest dynamics in boreal Fennoscandia: a review and classification. Silva Fenn 45(5):823–841

Kuuluvainen T, Gauthier S (2018) Young and old forest in the boreal: critical stages of ecosystem dynamics and management under global change. Forest Ecosyst 5:26

Kuuluvainen T, Mäki J, Karjalainen L, Lehtonen H (2002) Tree age distributions in old-growth forest sites in Vienansalo wilderness, eastern Fennoscandia. Silva Fenn 36(1):169–184

Lähde E, Laiho O, Norokopi Y (1999) Diversity-oriented silviculture in the Boreal Zone of Europe. Forest Ecol Manag 118:223–243

Lilja S, Kuuluvainen T (2005) Structure of old Pinus sylvestris dominated forest stands along a geographic and human impact gradient in mid-boreal Fennoscandia. Silva Fenn 39(3):407–428

Lindenmayer D, Franklin J (2002) Conserving forest biodiversity: a comprehensive multiscaled approach. Island Press, Washington DC, pp 3–15

Lindenmayer D, Laurance W, Franklin J (2012) Global decline in large old trees. Science 338:1305–1306

Lindenmayer D, Laurance W, Franklin J, Banks S, Blanchard W, Gibbons P, Ikin K, Blair D, McBurney L, Manning A, Stein J (2014) New policies for old trees: averting a global crisis in a keystone ecological structure. Conserv Lett 7(1):61–69

Linder P (1998) Structural changes in two virgin boreal forest stands in central Sweden over 72 years. Scand J Forest Res 13(1):451–461

Lommi S, Berglund H, Kuusinen M, Kuuluvainen T (2009) Epiphytic lichen diversity in late-successional Pinus sylvestris forests along local and regional forest utilization gradients in eastern boreal Fennoscandia. Forest Ecol Manag 259:883–892

Naeem S, Chapin C, Costanza R, Ehrlich P, Golley F, Hooper D, Lawton JH, Neil R, Mooney H, Sala O, Symstad A, Tilman D (1999) Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning: maintaining natural life support processes. Issues Ecol 4:2–12

National board of survey geographical society of Finland (1987) Atlas of Finland. Appendix 131 Climate

National board of survey geographical society of Finland (1990) Atlas of Finland. Appendix 123–126 Geology

Nazarova L (2011) Regional climate change (Karelia, Russia). Environment Technology Resources. Proceedings of the 8th International Scientific and Practical Conference Vol II. RA Izdevniecība, Rēzekne

Nordlind E, Östlund L (2003) Retrospective comparative analysis as a tool for ecological restoration: a case study in a Swedish boreal forest. Forestry 76(2):243–251

Paillet Y, Berges L, Hjalten J, Odor P, Avon C, Bernhardt-Romermann M, Bijlsma R, de Bruyn L, Fuhr M, Grandin U, Kanka R, Lundin L, Luque S, Magura T, Matesanz S, Meszaros I, Sebastia M, Schmidt W, Standovar T, Tothmeresz B, Uotila A, Valladares F, Vellak K, Virtanen R (2009) Biodiversity differences between managed and unmanaged forests: meta-analysis of species richness in Europe. Conserv Biol 24(1):101–112

Perry D, Oren R, Hart S (2008) Forest ecosystems, 2nd edn. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, pp 156–215

Peterson G, Allen C, Holling C (1998) Ecological resilience, biodiversity, and scale. Ecosystems 1:6–18

Pielou E (1966) The measurement of diversity in different types of biological collections. J Theor Biol 13:131–144

Pitkänen S (1998) The use of diversity indices to assess the diversity of vegetation in managed boreal forests. Forest Ecol Manag 112:121–137

Pommerening A (2002) Approaches to quantifying forest structures. Forestry 75(3):205–324

Pommerening A (2006) Evaluating structural indices by reversing forest structural analysis. Forest Ecol Manag 224:266–277

Pyykkö J (1996) Survey in Russian Karelian natural forests in Vienansalo. WWF Finland Report

Rouvinen S, Kuuluvainen T (2005) Tree diameter distributions in natural and managed old Pinus sylvestris-dominated forests. Forest Ecol Manag 208:45–61

Rouvinen S, Kuuluvainen T, Karjalainen L (2002a) Coarse woody debris in old Pinus sylvestris dominated forests along a geographic and human impact gradient in boreal Fennoscandia. Can J For Res 32:2184–2200

Rouvinen S, Kuuluvainen T, Siitonen J (2002b) Tree mortality in a Pinus sylvestris dominated boreal forest landscape in Vienansalo wilderness, eastern Fennoscandia. Silva Fenn 36(1):127–145

Saarinen K, Jantunen J, Saarnio S, Kuitunen K, Marttila O (2001) Effects of land use changes on the landscape composition: a comparison between Finnish and Russian Karelia. Environ Dev Sustain 3:265

Siitonen J (2001) Forest management, coarse woody debris and saproxylic organisms: Fennoscandian boreal forests as an example. Ecol Bull 49:11–41

Siitonen J, Martikainen P, Punttila P, Rauh J (2000) Coarse woody debris and stand characteristics in mature managed and old-growth boreal mesic forests in southern Finland. Forest Ecol Manag 128:211–225

Simberloff D (1972) Properties of the rarefaction diversity measurement. Am Nat 106:414–418

Spies TA (1998) Forest structure: a key to the ecosystem. In: Trofymow JA, MacKinno A (eds) Proceedings of a workshop on Structure, Process, and Diversity in Successional Forests of Coastal British Columbia, Victoria, 1998, pp 34–39

Sturtevant B, Bissonette J, Long J, Roberts D (1997) Coarse woody debris as a function of age, stand structure, and disturbance in boreal Newfoundland. Ecol Appl 7(2):702–712

Tipper JC (1979) Rarefaction and rarefiction-the use and abuse of a method in paleoecology. Paleobiology 5:423–443

von Gadow K, Zhang CY, Wehenkel C, Pommerening A, Corral-Rivas J, Korol M, Myklush S, Hui GY, Kiviste A, Zhao XH (2012) Forest structure and diversity. In: Pukkala T, von Gadow K (eds) Continuous cover forestry. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 29–83

Wallenius T, Kuuluvainen T, Heikkilä R, Lindholm T (2002) Spatial tree age structure and fire history in two old-growth forests in eastern Fennoscandia. Silva Fenn 36(1):185–199

Wallenius T, Kuuluvainen T, Vanha-Majamaa I (2004) Fire history in relation to site type and vegetation in Vienansalo wilderness in eastern Fennoscandia, Russia. Can J For Res 34:1400–1409

Ylläsjärvi I, Kuuluvainen T (2009) How homogeneous is the boreal forest? Characteristics and variability of old-growth forest on a Hylocomium-Myrtillus site type in the Pallas-Yllästunturi National Park, northern Finland. Ann Bot Fenn 46:263–279

Zhang L, Gove J, Liu C, Leak W (2001) A finite mixture of two Weibull distributions for modeling the diameter distributions of rotated-sigmoid, uneven-aged stands. Can J For Res 31:1654–1659

Acknowledgments

We thank the University of Helsinki boreal forest dynamics and biodiversity research group for the data used in the analysis of this research. We also thank Dr. Tuomas Aakala and Dr. Olli-Pekka Tikkanen for their insightful comments.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GQ analyzed and interpreted the data on diametric-species diversity and prepared the manuscript. TK provided the data, verified the methods used were correct to achieve the main goals of the research and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

de Quesada, G., Kuuluvainen, T. Tree diametric-species diversity is affected by human impact in old Scots pine dominated forest in boreal Fennoscandia. For. Ecosyst. 7, 8 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-020-0219-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-020-0219-6