Abstract

The biosynthesis of poly(lactic acid) (PLA)-like polymers, composed of >99 mol% lactate and a trace amount of 3-hydroxybutyrate, in engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum consists of two steps; the generation of the monomer substrate lactyl-coenzyme A (CoA) and the polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) synthase-catalyzed polymerization of lactyl-CoA. In order to increase polymer productivity, we explored the rate-limiting step in PLA-like polymer synthesis based on quantitative metabolite analysis using liquid chromatography mass spectroscopy (LC-MS). A significant pool of lactyl-CoA was found during polymer synthesis. This result suggested that the rate-limitation occurred at the polymerization step. Accordingly, the expression level of PHA synthase was increased by means of codon-optimization of the corresponding gene that consequently led to an increase in polymer content by 4.4-fold compared to the control. Notably, the codon-optimization did not significantly affect the concentration of lactyl-CoA, suggesting that the polymerization reaction was still the rate-limiting step upon the overexpression of PHA synthase. Another important finding was that the generation of lactyl-CoA was concomitant with a decrease in the acetyl-CoA level, indicating that acetyl-CoA served as a CoA donor for lactyl-CoA synthesis. These results show that obtaining information on the metabolite concentrations is highly useful for improving PLA-like polymer production. This strategy should be applicable to a wide range of PHA-producing systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Bacterial polyesters polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) are synthesized via the supply of monomer hydroxyacyl-CoA molecules and polymerization of the monomers catalyzed by PHA synthases (Rehm [2003]; Matsumoto and Taguchi [2013b]; Lu et al. [2009]). The rate-limiting step in PHA synthesis may be either the monomer supply or polymerization, which can vary depending on the combination of the relevant enzymes, production hosts and carbon source. To date, the rate-limiting step has been estimated by modulating the activity of each step to see its effect on polymer productivity (Jung et al. [2000]; Kichise et al. [1999]; Taguchi et al. [2001]). This indirect approach, however, was unable to provide quantitative information on the metabolic pathways. The aim of this study was to determine the intracellular concentration of the metabolic intermediates in the PHA biosynthetic pathways in order to explore the rate-limiting step.

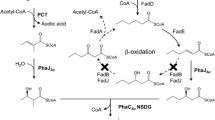

In this study, we chose the PLA-like polymer-producing Corynebacterium glutamicum as the target (Song et al. [2012]). This microorganism, which is known as an industrial amino acid producer with GRAS (Generally Regarded As Safe) status, has been engineered to express three exogenous genes encoding D-lactate dehydrogenase, propionyl-CoA transferase (PCT) and LA-polymerizing PHA synthase (PhaC1PsSTQK) (Taguchi and Doi [2004]; Taguchi et al. [2008]) (see pathway in Figure 1). This unique bacterial system was shown to be capable of producing PLA-like polymer directly from glucose via one-pot fermentation. It should be noted that the PLA-like polymer consists of >99 mol% LA and a trace amount of 3-hydroxybutyrate (3HB) (Song et al. [2012]), and thus is here referred to as PLA'. The challenge of the system was that had to be overcome was the low productivity of the polymer (0.03 g/L) compared to typical bacterial PHAs.

Metabolic pathway for PLA-like polymer production in engineered C. glutamicum . PLA-like polymers contained <1 mol% 3HB units. L-LDH, L-lactate dehydrogenase; D-LDH, D-lactate dehydrogenase; PCT, propionyl-CoA transferase; PhaC1STQK, lactate-polymerizing PHA synthase. The bold letters indicate exogenous enzymes. The dashed lines indicate the putative pathways. The dotted line indicates a very weak pathway. The gray ovals indicate significantly pooled metabolites.

To meet this challenge, we attempted to identify the rate-limiting step in PLA' synthesis by means of quantitative metabolite analysis using liquid chromatography mass spectroscopy (LC-MS) (Zhou et al. [2012]). This method was reported to be suitable for measuring the derivatives of CoA having a relatively high molecular weight and polarity, while gas chromatography-MS has been used for detecting relatively low-polarity and small molecules (Poblete-Castro et al. [2012]). In this study, the concentrations of the important intermediates for PLA' production were determined, i.e. lactyl-CoA, acetyl-CoA, acetoacetyl-CoA and 3HB-CoA (Figure 1). To the best of our knowledge this was the first successful monitoring of the intracellular CoA-derivatives during PLA' production, which was realized by a rational metabolic engineering approach.

Materials and methods

Plasmid construction

The four oligonucleotides 5'-gtcaccggatcccggttaactctag-3', 5'-actcgagcctgcaggagatcttcgatatca-3', 5'-ctagtgatatcgaagatctcctgc-3' and 5'-aggctcgagtctagagttaaccgggatccg-3' were inserted into the Xba I/Bst EII sites of pPSPTG1 (Song et al. [2012]) so as to create Bam HI, Hpa I, Xba I, Xho I, Sbf I, Bgl II and Eco RV sites (pPSDCP). Fragments of the ldhA gene from Escherichia coli (gene ID: 12930508), the pct gene from Megasphaera elsdenii and the phaC1STQK gene (Taguchi et al. [2008]) were inserted into pPSDCP at Bam HI/Hpa I, Bgl II/Eco RV and Xba I/Bgl II sites, respectively, to yield pPSldhAC1STQKpct. The codon-optimized phaC1STQK gene [ephaC1STQK, accession No. AB983346 (DDBJ)] was chemically synthesized (Eurofins Genomics) for the expression in C. glutamicum and its Xba I/Sbf I fragment was inserted in a similar manner so as to yield pPSldhAeC1STQKpct (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Strain, culture conditions and polymer analysis

C. glutamicum ATCC13803 was transformed by electroporation, as described previously (Liebl et al. [1989]). For polymer production, the engineered strains were grown in 2 ml nutrient-rich CM2G medium (Kikuchi et al. [2003]) at 30°C for 24 h with reciprocal shaking at 180 strokes/min. Two hundred microliters of the preculture were then transferred into 2 mL minimal MMTG medium (Kikuchi et al. [2003]) containing 60 g/L glucose and 0.45 mg/L of biotin, and further cultivated for 72 h at 30°C. When needed, kanamycin (50 μg/mL) was added to the medium. After cultivation, cells were lyophilized for polymer extraction. The polymer content was determined using gas chromatography as described previously (Takase et al. [2004]). Based on this analytical method, 3HB units in the polymer were below the detection limit.

LC-MS analysis

The cell extract was prepared using a method modified from a previous report (Kiefer et al. [2011]). The cells were cultivated on 2 mL MMTG medium as described above, then harvested at 18 h. The cells were resuspended in 200 μL of chilled water, then combined with 1 mL chilled acetonitrile containing 0.1 M formic acid and treated with sonication for 5 sec × 5 times. The supernatant was transferred to a new microtube and evaporated in vacuo at 4°C. The sample was dissolved in 200 μL of chilled water. LC-MS analysis was performed using an LCMS-8030 (Shimadzu) equipped with a Mastro C18 column (150 mm), electrospray ionization (ESI) and triple quadrupole mass spectroscopy. Carrier A: 5 mM ammonium acetate (pH 5.6) containing 5 mM dimethylbutylamine (Gao et al. [2007]) and carrier B: methanol were used with a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min in gradient mode, as follows: 0 min, 10% B; 3 min, 10% B; 15 min, 95% B; 18 min, 95% B; 23 min, 10% B. The ESI voltage was 3.5 kV in the negative mode. Nitrogen was used as a nebulizer (3.0 mL/min) and drying gas (15.0 mL/min). [M-H]- ions from acetyl-CoA (m/z = 808, retention time: 9.1 min), acetoacetyl-CoA (m/z = 850, rt: 8.9 min), 3HB-CoA (m/z = 852, rt: 9.1 min) and lactyl-CoA (m/z = 838, rt: 8.7 min) were monitored using the selected ion monitoring mode. Acetyl-CoA, acetoacetyl-CoA and 3HB-CoA, used as standards, were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Lactyl-CoA was synthesized via CoA-transferring reaction by PCT, as follows. The reaction mixture containing 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 0.4 mM acetyl-CoA, 12.5 mM sodium lactate and 0.1 mg/mL purified His-tagged PCT (Additional file 1) was incubated at 30°C for 30 min. Then lactyl-CoA was purified using a preparative HPLC equipped with a C18 reverse phase column.

SDS-PAGE analysis

The cells cultivated under the polymer producing conditions were harvested at 18 h. The cells were resuspended in 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) buffer and treated with sonication. The whole cell extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE.

Results

The use of a single plasmid system increased transformation efficiency

In a previous study, a dual plasmid system using pPS and pVC vectors was used for PLA' production (Song et al. [2012]). To reduce the use of antibiotics, the expression vector was reconstructed so that the recombinant form was maintained only in the presence of kanamycin. In addition, the single plasmid system improved the transformation efficiency compared to the dual plasmid system (from 3 × 102 to 2 × 104 colonies/μg DNA). Therefore, the single plasmid system was used for further study.

Determination of the CoA intermediates in the engineered C. glutamicum

The wild-type C. glutamicum and the recombinant cells harboring pPSldhAC1STQKpct were cultivated under the polymer-producing conditions. The cells were harvested in the logarithmic growth phase (18 h) and subjected to metabolite analysis. The concentrations of aectyl-CoA, lactyl-CoA, acetoacetyl-CoA and 3HB-CoA in the cells were determined. The key points for the successful measurement of the CoA derivatives were shown to be a rapid extraction of the cells along with the an appropriate ion pair reagent. For the wild-type cells, the acetyl-CoA concentration was 89 nmol/g-dry cells, and unexpectedly, a small amount of lactyl-CoA was also observed (Figure 2). In contrast, the recombinant cells exhibited an elevated concentration of lactyl-CoA, which was concomitant with a significant reduction in the concentration of acetyl-CoA. This result suggests that PCT promoted lactyl-CoA synthesis, and more importantly, acetyl-CoA is able to serve as a CoA donor for the generation of lactyl-CoA (Figure 1). The concentrations of acetoacetyl-CoA and 3HB-CoA were below the detection limit for all of the conditions tested (data not shown). From these observations, the interconversion of lactate + acetyl-CoA ↔ lactyl-CoA + acetate presumably achieved an equilibrium state, namely, the polymerization of lactyl-CoA would be a retarded step.

Enhanced expression of PHA synthase elevated PLA-like polymer production

In order to evaluate the aforementioned hypothesis and to overcome the existing limitation, we attempted to improve the expression level of PHA synthase. For this purpose, the codon-optimized PHA synthase gene ephaC1PsSTQK, which was supposed to be efficiently translated in C. glutamicum, was synthesized. First, the effect of the codon-optimization on the expression of the enzyme was evaluated. As shown in Figure 3, the cells harboring the codon-optimized gene had an increase in the expression level of PHA synthase.

SDS-PAGE analysis of C. glutamicum . Whole cell extracts were applied. The arrow indicates the size of PhaC1STQK. 1: Purified His-tag fusion of PhaC1STQK (0.072 μg), 2: size marker, 3: wild type (5.4 μg), 4: recombinant form harboring the parent PHA synthase gene phaC1STQK (5.0 μg), 5 : recombinant form harboring the codon-optimized ephaC1STQK gene (4.0 μg).

Next, the PLA' production was investigated for the cells harboring parent and codon-optimized PHA synthase genes. As expected, the cells expressing a higher level of PHA synthase accumulated more PLA' (4.4-fold) than the control (Table 1). Thus, the metabolic engineering, which was designed based on the metabolite analysis, did successfully improve the polymer production. In addition, this result supported the validity of the method for the determination of the metabolite concentrations.

Metabolite analysis of the modified cells indicated the rate-limiting step remained

The metabolite concentrations in the cells harboring the codon-optimized gene were measured. Despite the increase in the polymer content (Table 1), there was no significant difference between the metabolite levels in the two types of recombinant cells (Figure 2). This result indicated that the rate-limiting at polymerization step remained even with the reinforced expression of PHA synthase.

Discussion

In this study, metabolite analysis was shown to provide quantitative information that was very useful for addressing the rate-limiting step in the PLA' production. In the previous studies, the rate-limiting step in PHA production has been only qualitatively explored based on the polymer production in vivo. For examples, in the case of P(3HB) production in C. glutamicum, the expression of the highly active acetoacetyl-CoA reductase (PhaB) mutant from Ralstonia eutropha improved P(3HB) production (Matsumoto et al. [2013]), suggesting that monomer supply is a rate-limiting step in P(3HB) synthesis. A similar result was obtained in transgenic P(3HB)-producing tobacco (Matsumoto et al. [2011]). Here it should be noted that in these studies it was impossible to determine whether the improved the PhaB activity was sufficient or not unless the PhaB activity was further increased. In other words, P(3HB) production should reach a plateau if the PhaB activity was sufficient under the original conditions. In contrast, based on the metabolite analysis, the rate-limitation of PLA' synthesis at polymerization step was shown to remain after PHA synthase was overexpressed. Therefore, it was expected that an additional enhancement in polymerizing activity would be needed to increase PLA' production.

It was a chance discovery that the engineered C. glutamicum expressing PhaC1PsSTQK synthesized PLA'. On the other hand, it has been reportedly demonstrated that E. coli engineered to express the same set of enzymes did not produce PLA' (Nduko et al. [2013]; Shozui et al. [2011]; Yamada et al. [2009]; Matsumoto and Taguchi [2013a]). Thus, the mechanism for PLA' synthesis in C. glutamicum has been an important issue. A clue for answering this question might be the small amount of 3HB units (<1 mol%) incorporated into the polymer (Song et al. [2012]). The presence of 3HB units in the polymer suggests that this organism is likely to possess intrinsic 3HB-CoA (Figure 1). The result of the present study, however, demonstrated that the concentration of 3HB-CoA was below the detection limit. Thus, 3HB-CoA may be synthesized via an unidentified, very weak route and/or rapidly metabolized. In comparison, in R. eutropha, which is an efficient P(3HB) producer, a much higher concentration of 3HB-CoA (0.1-1 nmol/g-dry cells) has been reportedly observed (Fukui et al. [2014]). The very low 3HB-CoA level in C. glutamicum might account for the capacity of this organism to produce the copolymer with an extremely high LA fraction. Further investigation of LA-based polymer-producing E. coli is needed to clarify this issue.

The wild-type C. glutamicum unexpectedly synthesized lactyl-CoA or another compound having the same m/z and retention time. The metabolite level was too low to be detected using the MS/MS mode. Thus, currently the molecule is not confidently identified. However, if the existence of lactyl-CoA is postulated, this molecule should be L-lactyl-CoA, which cannot be incorporated into the polymer due to the strict stereospecificity of PHA synthase (Tajima et al. [2009]), because the wild-type C. glutamicum possesses no D-LDH gene (Kalinowski et al. [2003]). To date, the presence of lactyl-CoA in C. glutamicum has not been reported and its physiological role is unknown. Thus it may be an interesting research target.

Although PLA' production was successfully increased by the overexpression of PHA synthase (Table 1), the polymer content was lower than previously reported results (up to 1.4 wt%) obtained using100 mL-scale flask cultures (Song et al. [2012]). This difference was probably due to the aeration efficiencies in the test tubes and flasks. Because the lactic acid production in C. glutamicum is influenced by the oxygen supply (Inui et al. [2004]), the aeration rate would be expected to have an impact on PLA' production. More detailed analysis and fine-tuning of the aeration using a jar-fermentor is needed to optimize the culture conditions.

In summary, the levels of CoA derivatives in engineered C. glutamicum during PLA' production were determined, which allowed us to identify a rate-limitation at the polymerization step. In fact, overexpression of PHA synthase successfully increased the polymer production. In addition, acetyl-CoA probably served as a CoA donor for supplying lactyl-CoA in C. glutamicum.

Additional file

References

Fukui T, Chou K, Harada K, Orita I, Nakayama Y, Bamba T, Nakamura S, Fukusaki E: Metabolite profiles of polyhydroxyalkanoate-producing Ralstonia eutropha H16. Metabolomics 2014, 10(2):190–202. 10.1007/s11306-013-0567-0

Gao L, Chiou W, Tang H, Cheng XH, Camp HS, Burns DJ: Simultaneous quantification of malonyl-CoA and several other short-chain acyl-CoAs in animal tissues by ion-pairing reversed-phase HPLC/MS. J Chromatogr B 2007, 853(1-2):303–313. 10.1016/j.jchromb.2007.03.029

Inui M, Murakami S, Okino S, Kawaguchi H, Vertes AA, Yukawa H: Metabolic analysis of Corynebacterium glutamicum during lactate and succinate productions under oxygen deprivation conditions. J Mol Microb Biotech 2004, 7(4):182–196. 10.1159/000079827

Jung Y, Park J, Lee Y: Metabolic engineering of Alcaligenes eutrophus through the transformation of cloned phbCAB genes for the investigation of the regulatory mechanism of polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis. Enzyme Microb Technol 2000, 26(2-4):201–208. 10.1016/S0141-0229(99)00156-8

Kalinowski J, Bathe B, Bartels D, Bischoff N, Bott M, Burkovski A, Dusch N, Eggeling L, Eikmanns BJ, Gaigalat L, Goesmann A, Hartmann M, Huthmacher K, Kramer R, Linke B, McHardy AC, Meyer F, Mockel B, Pfefferle W, Puhler A, Rey DA, Ruckert C, Rupp O, Sahm H, Wendisch VF, Wiegrabe I, Tauch A: The complete Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032 genome sequence and its impact on the production of L-aspartate-derived amino acids and vitamins. J Biotechnol 2003, 104(1-3):5–25. 10.1016/S0168-1656(03)00154-8

Kichise T, Fukui T, Yoshida Y, Doi Y: Biosynthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) by recombinant Ralstonia eutropha and effects of PHA synthase activity on in vivo PHA biosynthesis. Int J Biol Macromol 1999, 25(1-3):69–77. 10.1016/S0141-8130(99)00017-3

Kiefer P, Delmotte N, Vorholt JA: Nanoscale ion-pair reversed-phase HPLC-MS for sensitive metabolome analysis. Anal Chem 2011, 83(3):850–855. 10.1021/ac102445r

Kikuchi Y, Date M, Yokoyama K, Umezawa Y, Matsui H: Secretion of active-form Streptoverticillium mobaraense transglutaminase by Corynebacterium glutamicum : processing of the pro-transglutaminase by a cosecreted subtilisin-Like protease from Streptomyces albogriseolus . Appl Environ Microbiol 2003, 69(1):358–366. 10.1128/AEM.69.1.358-366.2003

Liebl W, Bayerl A, Schein B, Stillner U, Schleifer KH: High efficiency electroporation of intact Corynebacterium glutamicum cells. FEMS Microbiol Lett 1989, 53(3):299–303. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1989.tb03677.x

Lu JN, Tappel RC, Nomura CT: Mini-review: Biosynthesis of poly(hydroxyalkanoates). Polym Rev 2009, 49(3):226–248. 10.1080/15583720903048243

Matsumoto K, Taguchi S: Biosynthetic polyesters consisting of 2-hydroxyalkanoic acids: current challenges and unresolved questions. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2013, 97(18):8011–8021. 10.1007/s00253-013-5120-6

Matsumoto K, Taguchi S: Enzyme and metabolic engineering for the production of novel biopolymers: crossover of biological and chemical processes. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2013, 24(6):1054–1060. 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.02.021

Matsumoto K, Morimoto K, Gohda A, Shimada H, Taguchi S: Improved polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) production in transgenic tobacco by enhancing translation efficiency of bacterial PHB biosynthetic genes. J Biosci Bioeng 2011, 111(4):485–488. 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2010.11.020

Matsumoto K, Tanaka Y, Watanabe T, Motohashi R, Ikeda K, Tobitani K, Yao M, Tanaka I, Taguchi S: Directed evolution and structural analysis of NADPH-dependent acetoacetyl Coenzyme A (acetoacetyl-CoA) reductase from Ralstonia eutropha reveals two mutations responsible for enhanced kinetics. Appl Environ Microbiol 2013, 79(19):6134–6139. 10.1128/AEM.01768-13

Nduko JM, Matsumoto K, Ooi T, Taguchi S: Effectiveness of xylose utilization for high yield production of lactate-enriched P(lactate- co -3-hydroxybutyrate) using a lactate-overproducing strain of Escherichia coli and an evolved lactate-polymerizing enzyme. Metab Eng 2013, 15: 159–166. 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.11.007

Poblete-Castro I, Escapa IF, Jaeger C, Puchalka J, Lam CMC, Schomburg D, Prieto MA, dos Santos VAPM: The metabolic response of P. putida KT2442 producing high levels of polyhydroxyalkanoate under single- and multiple-nutrient-limited growth: Highlights from a multi-level omics approach. Microb Cell Fact 2012, 11: 34. 10.1186/1475-2859-11-34

Rehm BHA: Polyester synthases: natural catalysts for plastics. Biochem J 2003, 376: 15–33. 10.1042/BJ20031254

Shozui F, Matsumoto K, Motohashi R, Sun JA, Satoh T, Kakuchi T, Taguchi S: Biosynthesis of a lactate (LA)-based polyester with a 96 mol% LA fraction and its application to stereocomplex formation. Polym Degrad Stab 2011, 96(4):499–504. 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2011.01.007

Song YY, Matsumoto K, Yamada M, Gohda A, Brigham CJ, Sinskey AJ, Taguchi S: Engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum as an endotoxin-free platform strain for lactate-based polyester production. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2012, 93(5):1917–1925. 10.1007/s00253-011-3718-0

Taguchi S, Doi Y: Evolution of polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) production system by "enzyme evolution": Successful case studies of directed evolution. Macromol Biosci 2004, 4(3):145–156. 10.1002/mabi.200300111

Taguchi S, Maehara A, Takase K, Nakahara M, Nakamura H, Doi Y: Analysis of mutational effects of a polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) polymerase on bacterial PHB accumulation using an in vivo assay system. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2001, 198(1):65–71. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10620.x

Taguchi S, Yamada M, Matsumoto K, Tajima K, Satoh Y, Munekata M, Ohno K, Kohda K, Shimamura T, Kambe H, Obata S: A microbial factory for lactate-based polyesters using a lactate-polymerizing enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008, 105(45):17323–17327. 10.1073/pnas.0805653105

Tajima K, Satoh Y, Satoh T, Itoh R, Han XR, Taguchi S, Kakuchi T, Munekata M: Chemo-enzymatic synthesis of poly(lactate- co -(3-hydroxybutyrate)) by a lactate-polymerizing enzyme. Macromolecules 2009, 42(6):1985–1989. 10.1021/ma802579g

Takase K, Matsumoto K, Taguchi S, Doi Y: Alteration of substrate chain-length specificity of type II synthase for polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis by in vitro evolution: in vivo and in vitro enzyme assays. Biomacromolecules 2004, 5(2):480–485. 10.1021/bm034323+

Yamada M, Matsumoto K, Nakai T, Taguchi S: Microbial production of lactate-enriched poly[( R )-lactate- co -( R )-3-hydroxybutyrate] with novel thermal properties. Biomacromolecules 2009, 10(4):677–681. 10.1021/bm8013846

Zhou B, Xiao JF, Tuli L, Ressom HW: LC-MS-based metabolomics. Mol Biosyst 2012, 8(2):470–481. 10.1039/c1mb05350g

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Japans Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Kakenhi (No. 26281043 to K.M., Nos. 23310059 and 26660080 to S.T. and No. 23580452 to T.O.), Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST), Precursory Research for Embryonic Science and Technology (PRESTO) and JST, CREST. Pacific Edit reviewed the manuscript prior to submission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

KM designed the study. KM wrote the manuscript TO and ST participated herein. KT performed the experiment work and developed LC-MS method. SA synthesized lactyl-CoA. YS developed protocols to manipulate C. glutamicum. All authors read and approved the submission of the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Matsumoto, K., Tobitani, K., Aoki, S. et al. Improved production of poly(lactic acid)-like polyester based on metabolite analysis to address the rate-limiting step. AMB Expr 4, 83 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-014-0083-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-014-0083-2