Abstract

Background

Enhancing empathy in healthcare education is a critical component in the development of a relationship between healthcare professionals and patients that would ensure better patient care; improved patient satisfaction, adherence to treatment, patients’ medication self-efficacy, improved treatment outcomes, and reduced patient anxiety. Unfortunately, however, the decline of empathy among students has been frequently reported. It is especially common when the curriculum transitions to a clinical setting. However, some studies have questioned the significance and frequency of this decline. Thus, the purpose of this study was to determine the impact of postgraduate clinical training on dental trainees’ empathy from cognitive, behavioral, and patients’ perspective.

Methods

This study included 64 trainee dentists at Okayama University Hospital and 13 simulated patients (SPs). The trainee dentists carried out initial medical interviews with SPs twice, at the beginning and the end of their clinical training. The trainees completed the Japanese version of the Jefferson Scale of Empathy for health professionals just before each medical interview. The SPs evaluated the trainees’ communication using an assessment questionnaire immediately after the medical interviews. The videotaped dialogue from the medical interviews was analyzed using the Roter Interaction Analysis System.

Results

No significant difference was found in the self-reported empathy score of trainees at the beginning and the end of the clinical training (107.73 [range, 85–134] vs. 108.34 [range, 69–138]; p = 0.643). Considering the results according to gender, male scored 104.06 (range, 88–118) vs. 101.06 (range, 71–122; p = 0.283) and female 109.17 (range, 85–134) vs. 111.20 (range, 69–138; p = 0.170). Similarly, there was no difference in the SPs’ evaluation of trainees’ communication (10.73 vs. 10.38, p = 0.434). Communication behavior in the emotional responsiveness category for trainees in the beginning was significantly higher than that at the end (2.47 vs. 1.14, p = 0.000).

Conclusions

Overall, a one-year postgraduate dental training program neither reduced nor increased trainee dentists’ empathy levels. Providing regular education support in this area may help trainees foster their empathy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Empathy is important in the relationship between healthcare professionals and patients, and is widely acknowledged as an efficient component of effective communication. Communicating with empathy helps the development of a therapeutic relationship. When patients are interviewed with empathic communication, they feel understood and accepted, and their concerns and problems are well elicited. If the healthcare professional understands the patient’s problems and how they view them, the professionals become more capable of making an accurate diagnosis, and formulating appropriate treatment plans [1, 2]. Empathy and its impact on professional communication are associated with improved patient satisfaction [3,4,5], adherence to treatment [6], patients’ medication self-efficacy [7], improved treatment outcomes [8], and reduced patient anxiety [9, 10].

Empathy is a multifaceted concept, which has cognitive, affective, and behavioral dimensions that were developed and integrated over time [11]. The Cambridge dictionary defines empathy as “the ability to share someone else’s feelings or experiences by imagining what it would be like to be in that person’s situation” [12]. However, its definition has not yet achieved consensus in the field.

Enhancing empathy is a critical concern in healthcare. Empathy can be fostered by raising awareness of the patient’s thoughts about the cause and importance of the patient’s problems. It can also be strengthened by acquiring appropriate listening skills to elicit patient’s concerns and problems. These skills help professionals treat patients with respect and in a caring manner which further leads to cultivation of humanistic behavior, one of the attributes of professionalism [13].

However, the decline of empathy levels among students during medical and dental education, especially after increased patient contact during clinical training, has frequently been demonstrated [14, 15]. Some factors contributing to the decline of empathy could be time constraints, patient care interactions, and a heavy load of study and work [16]. Yet, some reviews have suggested that the decline in empathy is considerably exaggerated. Díaz-Narváez and colleagues [17] reported various patterns of change in empathy levels during dental education. Colliver and colleagues [18] concluded that empathy decline may not be severe enough to affect patient care. To clarify this issue, we aimed to explore the impact of postgraduate clinical training that includes the opportunity to treat patients, on empathy among trainee dentists.

Most previous studies have used a single measurement for empathy, especially self-reported measures [16, 17, 19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. This may provide a limited understanding of empathy, because it is a multidimensional attribute. Colliver et al. [18] noted that the patients’ perceptions should be considered in assessing healthprofessionals’ empathy. Therefore, this study used three measures to assess empathy: the cognitive aspect, behavioral aspect, and patient perspective. The behavioral dimension was measured by the trainee dentists’ empathic communication, and the patients’ perspective was measured by the simulated patients’ (SPs) assessment of trainee communication during initial medical interviews.

The purpose of this study was to determine the impact of postgraduate clinical training on dental trainees’ empathy not just from a cognitive and behavioral perspective, but also from the patients’ perspective. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine changes in empathy during postgraduate training in dental education, assessed with multi-perspective measurements.

Methods

Participants

We chose the convenience sampling method for this study. The total number of trainee dentists that enrolled at the Okayama University Hospital for the one-year postgraduate clinical training course in 2017 and 2018 was 64. All 64 of them (18 males and 46 females) were recruited for the study. In addition, 13 SPs from the Okayama Working Group for Simulated Patients (11 females and two males) participated in the study. Ten SPs each participated in this study in 2017 and 2018, including seven SPs who participated both years. Participants were given both verbal and written explanations of the study and its procedure. All trainees provided their signed informed consent after confirming that they understand. All SPs provided consent via e-mail. Participants were reassured that choosing not to take part in the study would not affect their clinical training.

Overview of the postgraduate clinical training course for dentists at Okayama University Hospital

After graduating from high school, dental students in Japan enroll in a six-year undergraduate program, followed by a mandatory one-year clinical training program after acquiring their license. This training is comprehensive and intended to equip the trainees with skills to provide general dental care for the entire oral cavity and an emphasis on patient-centered holistic care.

The postgraduate program consisted of a combination of departments that provide proficiency training in basic and common treatments encountered in daily practice. Under the supervision of the senior dentists, the trainee dentists assist with treatment and also treat patients directly. Completing a minimum number of cases for general dentistry basic practices is required. An electronic portfolio is used to encourage the trainees to review their practice critically. After each session, the trainees write the details of the treatment they performed, what they noticed in this practice, and what they should change to improve moving forward. The supervising senior dentists comment on their portfolios, adopting a reflective and supportive approach to facilitate trainee learning. Case presentations and instructive seminars are also required.

Data collection procedure

Each trainee dentist conducted an initial medical interview with an SP twice: at the start and end of their training program. The medical interviews took place in a room in a medical office which is different from a consultation room. These medical interviews were a mandatory requirement of the regular training and were not specifically conducted for the purpose of research. However, the trainees consented to participating in this study and using the data from these interviews for this research.

Just before the initial medical interview with SPs, the trainee dentists completed the Japanese version of the Jefferson Scale of Empathy (JSE) for health professionals (HP-Version). Different dental problems were selected for presentation at the initial interview at the beginning of the training and the one at the end of the training. The former primarily presented concerns about the potential severity of persistent stomatitis on their tongues, while the latter primarily focused on the potential severity of persistent swelling and dull pain in their cheeks. We acknowledge that we should have examined the impact of the two different cases to further improve the validity of the study. The medical interviews were videotaped and had no time limitation. SPs evaluated the trainees’ communication using an assessment questionnaire immediately after the medical interviews.

Measures

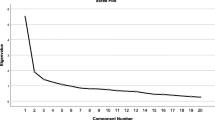

JSE (HP-Version): self‐assessment of trainees’ empathy

The JSE (HP-Version) is a self-reporting instrument developed to measure empathy specifically in physicians and health professionals [26]. Ample evidence has supported the reliability and validity of the JSE for students and healthcare professionals [27]. The JSE is an extensively used instrument that has been translated into 43 languages and used in over 60 countries [28]. The psychometric properties of its Japanese version have also been reported [29]. The internal consistency of the JSE for this study’s population was good; Cronbach’s alpha at the beginning and end of the training were 0.78 and 0.86, respectively.

The JSE consists of 20 items, each rated on a seven-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree), with possible total scores ranging from 20 to 140. Half of the items are reverse scored, so that an overall higher score shows a more empathic orientation toward patient care.

The Roter interaction analysis system (RIAS)

The RIAS was used to analyze the videotaped dialogue from the medical interviews. The RIAS is a method for coding medical dialogue and is most widely used in Western countries [30]. However, its applicability has also been reported for the Japanese population [31].

The dialogue is divided into ‘utterances’ that are defined as the smallest units in the medical interview. Units vary in length from single words to long sentences composed of one thought or piece of information. Each utterance falls into one of 41 mutually-exclusive code categories, excluding unintelligible utterances, according to the Japanese version of the RIAS [30]. In this study, six new categories were added to distinguish dental conversations from other medical conversations. The six new categories were originally included in the medical conversation, under both ‘Gathering medical data,’ and ‘Giving medical information.’ We then consolidated all categories into 14 larger composite clusters based on content similarity (Table 1).

Coding was performed directly from videotapes rather than transcripts; therefore, utterances can be categorized based on voice tone and phrasing cues as well as literal meaning.

Two coders (SW and TY) independently analyzed 20 videotapes that were not included in this study to assess inter-coder reliability. SW is a dentist with a PhD degree and TY is a faculty specialized in behavioral dentistry with a PhD degree and has a dental technician license. Both coders completed the RIAS coding training provided by RIAS Japan. Inter-class correlation coefficients were calculated between the results of the two coders for the categories with a mean frequency greater than two per medical interview. The average correlation was 0.69 (0.25–0.99) for trainee dentists and 0.74 (0.64–0.82) for SPs, indicating moderate coding reliability. In addition, 20 randomly selected videotapes in this study were independently double coded by the second coder (TY). The average correlation was 0.70 (0.46–0.84) for trainee dentists and 0.77 (0.49–0.88) for SPs, indicating moderate coding reliability. The main coder (SW) analyzed all videotapes in this study according to the RIAS Japan manual.

The frequency (the absolute number) of utterances for each category was used for the comparison instead of the percentage rate because there was no significant difference in the duration of the medical interview between the beginning and end of training.

SP assessment questionnaire of trainee dentists’ communication

The SP assessment questionnaire comprises five items included in Table 2, answered on a four-point scale (0 = disagree, 1 = somewhat disagree, 2 = somewhat agree, 3 = agree). The possible total scores ranged from 0 to 15, where a high score indicates a more positive assessment.

This questionnaire was prepared based on the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Patient Assessment survey questionnaire, which consists of 10 items [32]. Since that questionnaire was not prepared exclusively for medical interviews, the five question items which matched the initial interview were selected and the language was modified to make it easier for the Japanese SPs to understand. Cronbach’s alpha at the beginning and the end of the training were 0.82 and 0.88, respectively, which indicated good internal consistency.

Statistical analyses

The mean medical interview duration, the mean total JSE score, frequency of trainees’ and SPs’ utterances for each category, and total SP assessment score for the start and end of training were compared.

Paired t-test was used to evaluate the mean total JSE score because the data were normally distributed. The mean medical interview duration, the mean frequency of trainees’ and SPs’ utterances, and the mean SP assessment score were not expected to be normally distributed, and so the Wilcoxon signed-ranks test was utilized. All statistical analyses were conducted using the software SPSS version 24 (IBM, Tokyo, Japan). A significant difference was defined as > 0.05.

Results

All 64 trainee dentists who were enrolled for the one-year postgraduate clinical training course at the Okayama University Hospital in 2017 and 2018 were recruited, and all of them (aged 24–39 years, 18 males and 46 females) were participated.

Duration of the medical interview

The mean medical interview duration at the beginning and end of training were 8 minutes 44 seconds (SD, 2 minutes 25 seconds; range, 4 minutes 47 seconds to 16 minutes 35 seconds) and 8 minutes 7 seconds (SD, 2 minutes 27 seconds; range, 3 minutes 52 seconds to 15 minutes 41 seconds), respectively; these duration did not differ significantly (Z=-1.819; p = 0.069).

According to an existing study performed at a different dental school, the average duration for trainees was about 6 minutes [33], which is shorter than the times of our study. This may be due to the trainees in our study taking time to conduct the medical interview thoroughly.

JSE

The mean JSE total score for all trainee participants, as well as by gender, is provided in Table 3. The JSE total score averaged 107.73 (SD, 10.59; range, 85–134) at the beginning and 108.34 (SD, 14.05; range, 69–138) at the end; no significant difference between the two administrations is observed. Considering gender, there were also no significant differences between the two timepoints among male (104.06 [range, 88–118] vs. 101.06 [range, 71–122]) or among female (109.17[ range, 85–134] vs. 111.20 [range 69–138]).

RIAS

Tables 4 and 5 show the mean frequencies of trainees’ and SPs’ utterances for the clusters, respectively. The cluster names are shown in quotation marks in this article. There were no differences in the total number of trainees’ and SPs’ utterances between the two timepoints.

Compared with the trainee dentists at the start of their training, those at the end had less ‘Emotional expression’ by half (2.47 vs. 1.14), which included empathic and legitimizing statements. They were also less involved in ‘Gathering medical data’ pertinent medical conditions or therapeutic regimen issues as suggested by the drop in the score from 6.59 to 5.19 and ‘Gathering psychosocial data’ regarding psychosocial or lifestyle issues as suggested by the drop in the score from 1.23 to 0.75. However, they engaged in more ‘Gathering dental data’ including current or past dental history as indicated by the increase in the score from 20.00 to 23.52.

Consistent with the trainees’ results, SPs provided fewer ‘Emotional expression’ statements nearly by half (scores dropped from 1.23 to 0.63), including expressing their concerns and less ‘Providing medical information’ (scores dropped from 8.64 to 6.08) and ‘Providing psychosocial information’ by half (scores dropped from 5.70 to 2.75). However, they provided more dental data in the medical interview at the end of training (32.23 vs. 39.33).

SP assessment of trainee dentists’ communication

The individual item scores of the SP assessment at the beginning and the end of the training are shown in Table 2, which shows that the mean total scores of SP assessment at the beginning and end of the training were 10.73 (SD, 2.49; range, 6–15) and 10.38 (SD, 2.79; range, 5–15), respectively. No significant difference in mean total score was found between the two administrations. Only the score for the item ‘Did you feel your worries and anxiety were understood?’ was significantly lower at the end of training compared to the beginning.

Discussion

We examined what impact, as assessed by three indicators, does the course of a one-year postgraduate clinical training program have on empathy among Japanese trainee dentists. This study found that trainees’ self-reported empathy levels remained static, and communication behavior decreased in the emotional responsiveness category during trainees’ medical interviews. Additionally, the total score of SP assessment of trainees’ communication remained unchanged; however, there was a decline in trainees’ attitudes about accepting SPs’ concerns and anxiety from the SPs’ perspectives.

Although many studies reported declining self-assessed empathy at the clinical phase in both undergraduate education [16, 19,20,21] and during postgraduate residency [22, 34], unchanged stable empathy was found in our study, which was consistent with very few previous studies [35]. Some studies reported that the resident’s empathy score, measured using the same JSE, was comparable to our results [23, 36], and others reported increased results [34, 37]. As mentioned in an earlier study [38], the timing of clinical training varies by country, as does the number of years it takes to graduate. Therefore, differences in maturity may have led to differences in cognitive empathy by country.

On the other hand, we found decreased communication behavior in the emotional expression category for trainees, which may suggest that cognitive measures of empathy may not be completely in accordance with behavioral measures. Our finding was inconsistent with the results of an earlier study using the same measurements as ours, as this earlier study examined the relationship between communication behavior of medical students and their self-reported empathy and found that emotional responsiveness was among the predictors of the self-assessed empathy score [39].

One explanation for the decline in emotional expression in medical interviews could be that trainees are becoming more focused on their diagnosis and skills, which they view as crucial factors in treatment success. Our finding that trainees engaged in more data gathering, including a history of the current dental problem, would support this explanation. Holmes and colleagues [40] reported in their qualitative study exploring medical students’ clinical clerkship experience that students realized meeting a patient was a matter of gathering the information needed to make a diagnosis and present the information to the mentor.

Another possible explanation is that there was no change in empathy at the cognitive level because the measure used was a self-reporting instrument. It is possible that the trainees understand the need for empathy but find it difficult to express it in their behavior. Since the trainees are at the early stages of their careers, they may be unable to both collect relevant information for an accurate diagnosis and respond to patients’ emotions empathetically to draw out their concerns at the same time. It may take longer for them to learn to combine the ‘science’ of diagnosing and the ‘art’ of expressing empathy together in the medical interview. This speculation needs to be investigated in future research.

Another reason for the decline in the SP assessment regarding trainees’ understanding of SPs’ worries could be attributed to the decrease in the trainees’ empathic communication. When the trainees do not demonstrate much empathy in their communication with SPs, SPs may perceive that the trainees are reluctant to understand them. The decrease in SPs’ empathic expression may also be related to the decline of the SPs’ assessments, because communication is a reciprocal interaction. The decrease in the trainees’ legitimizing and empathic communication may have prevented patients from raising concerns. This was consistent with our previous study [41].

Moreover, some studies that showed an increase in dental students’ empathy noted this could be due to recently-completed communication lectures and practices [24]. Training in communication skills, including role playing with SPs who provide feedback, is effective in increasing empathy, but the effect is not sustained [25]. Although we provided medical interviewing training just before the start of this study, specific communication instruction focused on empathy was not implemented during the rest of their residency in the present study. Thus, it may be helpful to regularly provide some practice focused on empathetic communication skills during their training period. Although we have employed a portfolio for trainees to reflect on their practice, as well as for their instructors to review, the current system has not resulted in more empathetic students. Therefore, instructors may need to emphasize feedback not only on the trainees’ manual skills but also on patient communication.

This study had several limitations. First, it was conducted at a single institution with a small sample size. Second, we cannot eliminate the potential influence of gender on communication during the medical interview. Third, we also cannot exclude the potential observer bias which might affect SPs’ assessment. As the SPs were notified of the start and the end of the training, they may have expected the trainees to have improved drastically at the end of the training, which may have made their evaluations stricter than at the beginning. Fourth, we only analyzed communication during the medical interview and excluded other interactions, which may have affected the measurement of the behavioral aspect. In addition, we included nonverbal behaviors with utterances in the analysis, but did not include nonverbal behaviors without utterances in the analysis. Moreover, we only compared the number of communication behaviors and did not consider the context of where the communication behaviors were seen, which may limit results. It is desirable to include qualitative approach to fully understand empathy. It must also be noted that the trainees knew that the medical interviews were being video-taped and therefore it is possible that trainees may have been unable to act the way they usually do, or on the contrary, they may have behaved better than what they actually do in their daily practice. Lastly, the validity of the two cases should have been examined to further improve the validity of the study. Therefore, caution must be exercised before generalizing these findings. Further studies are required to verify these findings.

Conclusions

A one-year postgraduate dental training program may be insufficient to foster empathy both cognitively and behaviorally among trainee dental students and fulfill SPs’ satisfaction during the medical interview. Providing communication-focused training and instructor feedback on trainees’ empathic communication with patients regularly during clinical training may enhance empathy. Nevertheless, further research is required to demonstrate the effectiveness of these educational methods with more certainty.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available since the postgraduate student dentists’ confidential information are included, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- SPs::

-

simulated patients; JSE: Jefferson Scale of Empathy; RIAS: Roter Interaction Analysis System

References

Suchman AL, Markakis K, Beckman HB, Frankel R. A model of empathic communication in the medical interview. JAMA. 1997;277:678–82.

Norfolk T, Birdi K, Walsh D. The role of empathy in establishing rapport in the consultation: a new model. Med Educ. 2007;41:690–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02789.x.

Bertakis KD, Roter D, Putnam SM. The relationship of physician medical interview style to patient satisfaction. J Fam Pract. 1991;32:175–81.

Ong LM, Visser MR, Lammes FB, de Haes JC. Doctor–patient communication and cancer patients’ quality of life and satisfaction. Patient Educ Couns. 2000;41:145–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0738-3991(99)00108-1.

Wang H, Kline JA, Jackson BE, Laureano-Phillips J, Robinson RD, Cowden CD, d’Etienne JP, Arze SE, Zenarosa NR. Association between emergency physician self-reported empathy and patient satisfaction. PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0204113. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204113.

Wachira J, Middlestadt S, Reece M, Peng CY, Braitstein P. Physician communication behaviors from the perspective of adult HIV patients in Kenya. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26:190–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzu004.

Flickinger TE, Saha S, Roter D, Korthuis PT, Sharp V, Cohn J, Eggly S, Moore RD, Beach MC. Clinician empathy is associated with differences in patient–clinician communication behaviors and higher medication self-efficacy in HIV care. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99:220–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.09.001.

Hojat M, Louis DZ, Markham FW, Wender R, Rabinowitz C, Gonnella JS. Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Acad Med. 2011;86:359–64. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182086fe1.

Roter DL, Hall JA, Kern DE, Barker LR, Cole KA, Roca RP. Improving physicians’ interviewing skills and reducing patients’ emotional distress. A randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1877–84. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1995.00430170071009.

Bernson JM, Hallberg LR-M, Elfström ML, Hakeberg M. ‘Making dental care possible: a mutual affair.’ a grounded theory relating to adult patients with dental fear and regular dental treatment. Eur J Oral Sci. 2011;119:373–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0722.2011.00845.x.

Moudatsou M, Stavropoulou A, Philalithis A, Koukouli S. The role of empathy in health and social care professionals. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8:26. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8010026.

Cambridge Dictionary. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/empathy. Accessed 22 October 2020.

Markakis KM, Beckman HB, Suchman AL, Frankel RM. The path to professionalism: cultivating humanistic values and attitudes in residency training. Acad Med. 2000;75:141–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200002000-00009.

Neumann M, Edelhäuser F, Tauschel D, Fischer MR, Wirtz M, Woopen C, Haramati A, Scheffer C. Empathy decline and its reasons: a systematic review of studies with medical students and residents. Acad Med. 2011;86:996–1009. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318221e615.

Narang R, Mittal L, Saha S, Aggarwal VP, Sood P, Mehra S. Empathy among dental students: a systematic review of literature. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2019;37:316–26. https://doi.org/10.4103/JISPPD.JISPPD_72_19.

Hojat M, Vergare MJ, Maxwell K, Brainard G, Herrine SK, Isenberg GA, Veloski J, Gonnella JS. The devil is in the third year: A longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical school. Acad Med. 2009;84:1182–91. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b17e55.

Díaz-Narváez VP, Coronado AME, Bilbao JL, González F, Padilla M, Calzadilla-Nuñez A, Silva-Vetri MG, Arboleda J, Bullen M, Utsman R, et al. Reconsidering the ‘decline’ of dental student empathy within the course in Latin America. Acta Med Port. 2017;30:775–82. https://doi.org/10.20344/amp.8681.

Colliver JA, Conlee MJ, Verhulst SJ, Dorsey JK. Reports of the decline of empathy during medical education are greatly exaggerated: a reexamination of the research. Acad Med. 2010;85:588–93. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d281dc.

Sherman JJ, Cramer A. Measurement of changes in empathy during dental school. J Dent Educ. 2005;69:338–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.0022-0337.2005.69.3.tb03920.x.

Javed MQ. The evaluation of empathy level of undergraduate dental students in Pakistan: a cross-sectional study. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2019;31:402–6.

Hojat M, Shannon SC, DeSantis J, Speicher MR, Bragan L, Calabrese LH. Does empathy decline in the clinical phase of medical education? A nationwide, multi-institutional, cross-sectional study of students at DO-granting medical schools. Aca Med. 2020;95:911–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003175.

Bellini LM, Shea JA. Mood change and empathy decline persist during three years of internal medicine training. Acad Med. 2005;80:164–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200502000-00013.

Aggarwal VP, Garg R, Goyal N, Kaur P, Singhal S, Singla N, Gijwani D, Sharma A. Exploring the missing link—empathy among dental students: an institutional cross-sectional survey. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2016;13:419–23. https://doi.org/10.4103/1735-3327.192279.

Babar MG, Omar H, Lim LP, Khan SA, Mitha S, Ahmad SFB, Hasan SS. An assessment of dental students’ empathy levels in Malaysia. Int J Med Educ. 2013;4:223–9. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.5259.4513.

Kataoka H, Iwase T, Ogawa H, Mahmood S, Sato M, DeSantis J, Hojat M, Gonnella JS. Can communication skills training improve empathy? A six-year longitudinal study of medical students in Japan. Med Teach. 2019;41:195–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1460657.

Hojat M, Gonnella JS, Nasca TJ, Mangione S, Vergare M, Magee M. Physician empathy: definition, components, measurement, and relationship to gender and specialty. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1563–9. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1563.

Hojat M. Empathy in patient care: antecedents, development, measurement, and outcomes. Philadelphia (PA): Springer; 2007.

Hojat M, Erdmann JB, Gonnella JS. Personality assessments and outcomes in medical education and practice of medicine: AMEE guide No. 79. Med Teach. 2013;35:e1267-e301. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2013.785654.

Kataoka HU, Koide N, Ochi K, Hojat M, Gonnella JS. Measurement of empathy among Japanese medical students: psychometrics and score differences by gender and level of medical education. Acad Med. 2009;84:1192–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b180d4.

Noro I, Abe K, Ishikawa H. The Roter Method of Interaction Process Analysis System (RIAS). 2nd ed. Aichi: Sankeisha; 2011. Japanese.

Ishikawa H, Takayama T, Yamazaki Y, Seki Y, Katsumata N. Physician–patient communication and patient satisfaction in Japanese cancer consultations. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55:301–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00173-3.

Abadel FT, Hattab AS. Patients’ assessment of professionalism and communication skills of medical graduates. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:28. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-14-28.

Kita S, Onizuka C, Konoo T, Nagamatsu H, Terashita M. Communication analyses of the interaction between simulated patients and vocational trainee dentists in the medical interview using the Roter Interaction Analysis System. J Kyushu Dent Soc. 2012;66:52–65. In Japanese.

West CP, Huntington JL, Huschka MM, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, Kolars JC, Habermann TM, Shanafelt TD. A prospective study of the relationship between medical knowledge and professionalism among internal medicine residents. Acad Med. 2007;82:587–92. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180555fc5.

Mangione S, Kane GC, Caruso JW, Gonnella JS, Nasca TJ, Hojat M. Assessment of empathy in different years of internal medicine training. Med Teach. 2002;24:370–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590220145725.

Jin J, Li H, Song W, Jiang N, Zhao W, Wen D. The mediating role of psychological capital on the relation between distress and empathy of medical residents: a cross-sectional survey. Med Educ Online. 2020;25:1710326. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2019.1710326.

Foreback J, Kusz H, Lepisto BL, Pawlaczyk B. Empathy in internal medicine residents at community-based hospitals: a cross-sectional study. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2018;5. https://doi.org/10.1177/2382120518771352.

Roff S. Reconsidering the ‘decline’ of medical student empathy as reported in studies using the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy-Student version (JSPE-S). Med Teach. 2015;37:783–6. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2015.1009022.

LaNoue MD, Roter DL. Exploring patient-centeredness: the relationship between self-reported empathy and patient-centered communication in medical trainees. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101:1143–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.01.016.

Holmes CL, Miller H, Regehr G. (Almost) forgetting to care: an unanticipated source of empathy loss in clerkship. Med Educ. 2017;51:732–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13344.

Watanabe S, Yoshida T, Kono T, Taketa H, Shiotsu N, Shirai H, Torii Y. Relationship of trainee dentists’ self-reported empathy and communication behaviors with simulated patients’ assessment in medical interviews. PloS ONE. 2018;13:e0203970. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203970.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all of the trainee dentists and SPs who participated in the study. We also wish to thank the residents who helped with our data collection. Additionally, we would like to thank Editage for English language editing.

Funding

This work was supported by the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) (C) of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan under grant number: 17K12047. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, interpretation of data and preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (TY, SW, TK, HT, NS, HS, YN, and YT) were involved in the research design. TY, SW, TK, and HT were involved data collection and analysis of this study. TY, NS, HS, YN, and YT evaluated the credibility of the data analysis. TY worked substantially on writing the manuscript, and all authors revised and approved the final version of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Okayama University Graduate School of Medicine, Dentistry, and Pharmaceutical Sciences (No. 1706-050). Participants were given oral explanations and written documents regarding this study. All postgraduate students provided their signed consent after confirming their understanding. All SPs provided consent via e-mail.

Authors’ information

Toshiko Yoshida, MA, PhD, is an assistant professor at Center for Education in Medicine and Health Sciences (Dental Education), Okayama University Graduate School of Medicine, Dentistry, and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Okayama, Japan.

Sho Watanabe, DDS, PhD, is a clinical fellow at Comprehensive Dental Clinic, Okayama University Hospital, Okayama, Japan.

Takayuki Kono, DDS, PhD, is an assistant professor at Comprehensive Dental Clinic, Okayama University Hospital, Okayama, Japan.

Hiroaki Taketa, DDS, PhD, is an assistant professor at Comprehensive Dental Clinic, Okayama University Hospital, Okayama, Japan.

Noriko Shiotsu, DDS, PhD, is a clinical fellow at Comprehensive Dental Clinic, Okayama University Hospital, Okayama, Japan.

Hajime Shirai, DDS, PhD, is a lecturer at Comprehensive Dental Clinic, Okayama University Hospital, Okayama, Japan.

Yukie Nakai, DDS, PhD, is a professor at Department of Dental Hygiene, University of Shizuoka, Junior College, Shizuoka, Japan.

Yasuhiro Torii, DDS, PhD, is a professor at Comprehensive Dental Clinic, Okayama University Hospital, Okayama, Japan.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yoshida, T., Watanabe, S., Kono, T. et al. What impact does postgraduate clinical training have on empathy among Japanese trainee dentists?. BMC Med Educ 21, 53 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02481-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02481-y