Abstract

Background

Nerves and neurotrophic growth factors are emerging promoters of cancer growth. The precursor for Nerve Growth Factor (proNGF) is overexpressed in thyroid cancer, but its potential role as a clinical biomarker has not been reported. Here we have examined the value of proNGF as a serum and biopsy-rinse biomarker for thyroid cancer diagnosis.

Methods

Patients presenting for thyroid surgery or biopsy were enrolled in separate cohorts examining serum (n = 204, including 46 cases of thyroid cancer) and biopsy-rinse specimens (n = 188, including 26 cases of thyroid cancer). ProNGF levels in clinical samples were analysed by ELISA. Univariate and multivariate statistical analyses were used to compare proNGF levels with malignancy status and clinicopathological parameters.

Results

ProNGF was not detected in the majority of serum samples (176/204, 86%) and the detection of proNGF was not associated with thyroid cancer diagnosis. In the few cases where proNGF was detected in the serum, thyroidectomy did not affect proNGF concentration, demonstrating that the thyroid was not the source of serum proNGF. Intriguingly, an association between hyperthyroidism and serum proNGF was observed (OR 3.3, 95% CI 1.6–8.7 p = 0.02). In biopsy-rinse, proNGF was detected in 73/188 (39%) cases, with no association between proNGF and thyroid cancer. However, a significant positive association between follicular lesions and biopsy-rinse proNGF was found (OR 3.3, 95% CI 1.2–8.7, p = 0.02).

Conclusions

ProNGF levels in serum and biopsy-rinse are not increased in thyroid cancer and therefore proNGF is not a clinical biomarker for this condition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Thyroid cancer is a common endocrine malignancy. In the United States, an average of 14 new cases per 100,000 person are diagnosed each year, with an annual increase in incidence of 3.6% since 1974 [1]. This rise is due to a combination of increased diagnosis of clinically indolent cancers, and a true but small increase in aggressive cases, with a corresponding small rise in incidence-based mortality [1]. Thus, the timely diagnosis of clinically significant thyroid cancers is an important public health priority. These cancers must be distinguished from more common benign thyroid nodules, detected by ultrasound in 19–35% of adults [2]. At present, the diagnostic evaluation of nodular thyroid disease includes thyroid ultrasound and fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy [3]. Importantly, no current technique can accurately predict clinically significant cancers from indolent thyroid cancers, as demonstrated by the “epidemic” of non-lethal papillary thyroid cancer in countries that have introduced neck ultrasound screening programs [4]. Therefore, blood-based and biopsy-based biomarkers are needed to refine the diagnosis and prognosis of thyroid cancers [5,6,7].

Nerves and neurotrophic growth factors are emerging promoters of tumorigenesis and are increasingly regarded as potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets in oncology [8, 9]. The precursor for nerve growth factor (proNGF) has recently been shown to be overexpressed in thyroid cancer compared to benign thyroid tissues, suggesting utility as a discriminator in diagnostic testing [10]. ProNGF is a soluble 246 amino acid pro-peptide, transcribed from the nerve growth factor (NGF) gene on chromosome 1p13. ProNGF is cleaved into nerve growth factor (NGF) by tissue proconvertases such as furin and matrix metalloproteinases [11]. ProNGF has an established role in neural development in the foetus [12], and acts on neurons through interaction with specific NGF receptors to promote neural survival and differentiation, or apoptosis [11]. Interestingly, proNGF and its receptors have been associated with progression and aggressiveness of several cancers, including breast [13, 14], prostate [15], and melanoma [16]. In thyroid cancer, in addition to proNGF overexpression [10], the upregulation of proNGF/NGF receptors (the tyrosine kinase TrkA, the neurotrophin receptor p75NTR and the pro-neurotrophin receptor sortilin) has been reported [17], suggesting a role for proNGF in thyroid carcinogenesis and a potential value as a diagnostic or prognostic biomarker.

In the present study, we hypothesized that the overexpression of proNGF may lead to an increased level of proNGF in the serum of patients with thyroid cancer, as compared with benign thyroid conditions, and might represent a useful biomarker for diagnosis and risk stratification of nodular thyroid disease. Further, we hypothesized that proNGF protein may also be detected in the needle-rinse of thyroid biopsy specimens, in a similar manner to the needle-rinse techniques used for assaying for thyroglobulin [18] and calcitonin [19]. Here we report the results of studies evaluating these hypotheses in nodular thyroid disease.

Methods

Patients and samples

This study was approved by the Hunter New England Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/16/HNE/247), and all participants provided written informed consent. To collect serum, we conducted a prospective nested cohort study, enrolling patients undergoing thyroid surgery or thyroid fine-needle aspiration biopsy for investigation or management of thyroid disease. To collect biopsy material, we conducted a prospective cohort study of patients referred for thyroid FNA biopsy at a single high-volume clinic.

In both cohorts, patients were followed after bio specimen collection to obtain a final diagnosis of their thyroid disease based on histopathology (surgical patients) or a composite clinical assessment (clinical, ultrasound and FNA biopsy) for non-surgical patients. Relevant clinical data were extracted from the medical record to correlate levels of proNGF with age, sex, presence of hyperthyroidism (defined as thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) level < 0.1 mIU/L), and thyroid histopathology.

Serum study

Prior to thyroid surgery or thyroid biopsy, serum was drawn into a serum separator tube (surgery-only patients) or plain serum tube (biopsy-first patients), centrifuged to separate, then aliquoted and frozen at − 80 °C. Serum samples were assayed using a proNGF enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (see below) on the first or second freeze-thaw cycle only. Samples were run in triplicate at 1:20 dilution (to minimize matrix effects, as recommended by the manufacturer), with positive results confirmed on a second plate; and run with an in-house quality control (QC) samples of serum spiked with recombinant human proNGF (Biosensis Pty Ltd., Adelaide, Australia). 4-parameter logistic regression curves were fit using GraphPad Prism (v7.0 California, USA). All results above the limit of detection of 0.05 ng/mL (a functional limit of 1 ng/mL allowing for 20x dilution) were reported as proNGF positive.

Biopsy rinse study

Consecutive consenting adults over 18 years with a thyroid nodule graded as ‘Low-’, ‘Intermediate-’ or ‘High-risk’, according to the Sonographic Pattern stratification of the 2015 American Thyroid Association [3], were prospectively enrolled. Each nodule was biopsied using a 25 g needle with capillary action technique. After expulsion of the cellular material for diagnostic cytopathology, the needle was rinsed with 0.5 mL phosphate-buffered saline at 4 °C with the addition of protease inhibitors (cOmplete Mini, Roche, Manneheim Germany, Catalogue number 046931590011, 1 tablet per 10 mL), with subsequent refrigerated centrifugation to pellet red blood cells and insoluble debris. The supernatant containing solubilised proteins was removed and stored at − 80 °C prior to ELISA, performed without dilution in duplicate (due to constraints on sample volume) and analysed as above. This ‘needle-rinse’ technique is established as a sensitive method of detecting the thyroid-specific proteins thyroglobulin (an established biopsy-based tumour marker for metastatic thyroid cancer) [18] and calcitonin (an established biopsy-based tumour marker for medullary thyroid cancer) [19], and has the advantage of preserving cytological material for diagnostic purposes whilst potentially yielding additional information from the solubilised proteins. All results above the limit of detection of 0.05 ng/mL were reported as proNGF positive.

ProNGF ELISA validation

ProNGF was quantified using a human enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (BEK-2226; Biosensis Pty Ltd., Adelaide, Australia), with wells coated with an antibody raised against the N-terminal precursor domain of human proNGF. Heterophilic antibody blockers were added as recommended by the manufacturer [20] to a final concentration of 38 μg/mL.

Performance of the proNGF ELISA was confirmed using spike and recovery and linearity of dilution experiments (Additional file 1: Table S1). A mean of 96% spike recovery was obtained (range 80–128%) when assayed in the presence of supplied heterophilic antibody blockers. Mean recovery of the in-house QC sample, which was assayed across all plates, was 98 ± 22% for serum, and 117 ± 20% for rinse. The between assay coefficient of variation was 20%, and the within-assay coefficient of variation (between wells) was 3.6 ± 2.9%.

For serum, no difference in rates of proNGF detection were observed in samples collected in serum-separator (16% positive, n = 95) vs plain serum tubes (12% positive, n = 109) (unadjusted p = 0.42; adjusted for age, sex and thyroid hormone status p = 0.79), suggesting that proNGF is not sequestered in the gel layer of a serum separator tube. Additionally, no difference in levels of proNGF detection were observed in samples stored for more than 12 months (13%, n = 117), compared to less than 12 months (21%, n = 87) (unadjusted p = 0.21, adjusted for age, sex, thyroid cancer and hyperthyroidism p = 0.79), suggesting that endogenous proNGF is stable at − 80 °C for at least 12 months.

Statistical analysis

Power calculations were based on pilot data, using a power of 0.8 and two sided alpha of 0.05. For the serum study, to detect a 3-fold increase in proNGF levels in patients with cancer, above the background detection of proNGF cleavage products in 6–10% of healthy sera [21], 46 cases and 160 controls were required. For the biopsy study, the diagnostic performance of proNGF in histological specimens generated an area under the ROC curve of 0.94 [10]. Conservatively assuming that our tests generate an AUC ROC of 0.85, and that the minimum clinically significant value is 0.7, 28 cases with thyroid cancer and 124 benign nodules were required.

Between group comparisons were assessed categorically using the Pearson’s Chi-square test, and continuously using the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test, with multiple logistic regression to assess for potential interaction from clinical variables. Analyses were performed using the statistical software package Stata (version 14, Statacorp, Texas, USA).

Between 2014 and 2017, 204 patients with thyroid diseases were enrolled in the serum cohort (46 cases of thyroid cancer and 158 cases of benign thyroid conditions); and between 2016 and 2018, 183 patients with 188 nodules were enrolled in the biopsy cohort (26 cases of thyroid cancer and 162 benign nodules). Demographic and clinical information regarding the two cohorts are presented in Table 1.

Results

Serum proNGF concentration is not associated with thyroid cancer

Overall, 176/204 (86%) of serum samples were negative for proNGF. In the remaining 14% of serum samples in which proNGF could be detected, median serum proNGF concentration was 6.2 ng/mL (IQR 4.2–12.4 ng/mL). With respect to the primary hypothesis, positive serum proNGF was detected in 6/46 (13%) cases of thyroid cancer, and in 22/158 (14%) benign samples (p = 0.97). The 6 positive results in the malignant group occurred in 5/36 papillary thyroid cancers and 1/8 follicular/hurthle-cell thyroid cancers (Additional file 2: Table S2). Median proNGF levels were not significantly different between benign and malignant cohorts (Table 2). Therefore proNGF is not a serum biomarker for thyroid cancer diagnosis.

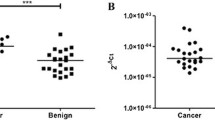

Post-thyroidectomy sera (range 2–14 days post-operative) were available for analysis, with 11 cases positive for proNGF, and 20 cases negative for proNGF. Figure 1a shows 10/11 (91%) cases with detectable pre-operative proNGF (median 5.8 ng/mL, IQR 4.9–8.2) remained positive in the post-thyroidectomy sample (median 2.8 ng/mL, IQR 2.1–4.5). 18/20 (90%) cases with negative pre-operative proNGF had a concordant post-thyroidectomy sample. As the in-vitro serum half-life of proNGF was determined to be 90 min (Fig. 1b), our results suggest that the proNGF detected in the serum was not of thyroid origin.

ProNGF serum levels after thyroidectomy and half-life. a Change in serum proNGF following total thyroidectomy. Pre- and post- thyroidectomy serum samples were available for 11 cases where pre-operative serum proNGF was detectable. No significant difference was detected between pre- and post- thyroidectomy levels of proNGF. b ProNGF in vitro half-life. Aliquots of serum negative for proNGF was spiked with 20 ng/mL recombinant proNGF dissolved in Assay Diluent A (Biosensis, Australia) in a 1:1 ratio, then incubated at 37 °C for increments of 24 h, then assayed at 1:20 dilution with Heterophilic Blocking Antibody (BL-003-1000). An exponential decay curve was fitted, giving an estimated in-vitro half-life in serum of 1.5 h. Similar results were obtained using phosphate-buffered-saline as diluent

Serum proNGF may be associated with hyperthyroidism

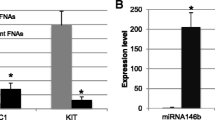

Analysis of serum proNGF data was undertaken in subgroups of hyperthyroidism, age and sex (Table 2). ProNGF was above 1 ng/mL in 9/28 (32%) of hyperthyroid cases, compared to 19/176 (11%) of euthyroid cases (Pearson’s chi-square p = 0.002, Fig. 2a). ProNGF levels were higher in sera from patients who were hyperthyroid at the time of sampling (TSH < 0.1mIU/L) than in those who were euthyroid (proNGF interquartile range 0–1.76 ng/mL vs 0-0 ng/mL respectively, Wilcoxon Rank-Sum p = 0.002, Fig. 2b). No difference was observed in proNGF levels based on age or sex or follicular lesions. Multiple logistic regression was performed to assess the interaction of thyroid cancer, age, sex, follicular lesion and hyperthyroid status on serum proNGF levels (Table 2). The odds ratio for serum proNGF > 1 ng/mL (compared to ≤1 ng/mL, the assay limit of detection) in the presence of hyperthyroidism, holding other variables constant, was 3.3 (95% CI 1.6–8.7 p = 0.02). No association was found with the other parameters, and there was no confounding observed.

Subgroup analysis of proNGF. a Bar graph showing detection of serum proNGF as a binary variable, stratified by hyperthyroid status. See Table 2 for details. b Box (interquartile range) and whisker (5–95% range) demonstrating detection of serum proNGF as a continuous variable, stratified by hyperthyroid status. See Table 2 for details. c Box (interquartile range) and whisker (5–95% range) graph showing concentration of proNGF in biopsy rinse, stratified the presence of follicular lesions. See Table 3 for details. d Scatter plot (with median and interquartile range overlaid) showing concentration of proNGF in biopsy-rinse, stratified by malignant status of follicular lesions. See Table 3 for details

Biopsy rinse proNGF is not associated with thyroid cancer

Overall, 73/188 (39%) of biopsy-rinse specimens were positive for proNGF. Median proNGF concentration in positive samples was 0.15 ng/mL (IQR 0.1–0.2 ng/mL). With respect to the primary hypothesis, biopsy-rinse proNGF was detected in 12/26 (46%) nodules with thyroid cancer, and in 61/162 (38%) benign nodules (p = 0.41). The 12 positive results in the malignant group occurred in 7/19 papillary thyroid cancers (37%) and 4/5 follicular/Hurthle-cell thyroid cancers (80%). Median proNGF levels were not significantly different between benign and malignant thyroid nodules (Table 3). Individual patient characteristics for the 73 cases of detectable proNGF are presented in Additional file 3: Table S3.

Biopsy rinse proNGF may be associated with follicular lesions

Analysis of the biopsy-rinse proNGF cohort was undertaken in subgroups of age, sex and follicular lesions (including follicular adenoma, Hurthle cell adenoma, follicular carcinoma and Hurthle cell carcinoma) (Table 3). Insufficient patients were hyperthyroid at the time of biopsy (as hyperfunctioning nodules have a low risk of malignancy and are rarely biopsied) for analysis of this cohort by hyperthyroid status (see Table 1). ProNGF levels were higher from follicular lesions (median 0.12 vs 0 ng/mL, p = 0.002) compared to other nodules (Fig. 2c). However, proNGF was detected at similar rates in both benign (9/15, 60%) and malignant (4/5, 80%) follicular lesions, suggesting that this is not a useful discriminative marker for follicular thyroid cancer (p = 0.42), and there was no difference in concentration of proNGF between benign and malignant follicular lesions (Fig. 2d, p = 0.34). Multiple logistic regression, dichotomizing biopsy proNGF at 0.05 ng/mL (negative/positive) as the dependent variable, and including model variables of age, sex, follicular lesion and malignant status, continued to demonstrate an association between proNGF and follicular lesions (odds ratio 3.3, 95% CI 1.2–8.7, p = 0.02), holding other parameters constant (Table 3). No other parameter showed significant association and there was no evidence of confounding.

Discussion

The over-diagnosis of clinically indolent thyroid cancer necessitates the development of biomarkers that better predict future disease aggressiveness to allow clinicians and patients to match treatment intensity with disease risk. An inexpensive protein-based biomarker in serum, or as an adjunct to needle biopsy, represents an attractive translational biomarker, and pilot data for proNGF suggested a possible utility for this protein in this role [10].

This present study, reporting proNGF evaluation in a large cohort of serum and biopsy material, found no difference in levels of proNGF between cases of thyroid cancer and other thyroid diseases. The study was adequately powered to detect clinically meaningful differences in proNGF levels. A smaller difference is unlikely to be clinically useful as a biomarker of thyroid malignancy. Therefore, the increased level of proNGF tissue expression in thyroid cancer previously observed [10] does not result in an increased proNGF concentration in the serum of thyroid cancer patients, or provide a sufficiently discriminatory level of proNGF in biopsy specimens, demonstrating that, based upon these data, serum and biopsy-rinse proNGF is not of clinical value for the diagnosis or prognosis of thyroid cancer.

A prior study has examined the presence of proNGF in sera of 20 patients with and without diabetic retinopathy, using Western blotting [22]. They found that a small subset of patients with diabetic retinopathy had detectable serum proNGF, although exact quantification was not possible due to the limitations of Western blot methodology. A study of 227 patients with autoimmune diseases measured LIP1 and LIP2 (short cleavage products of proNGF peptide) in serum using ELISA, with rates of positivity in control serum of 6 and 10% respectively. These findings are concordant with the present study [21]. Contrastingly, a recent study of 116 patients (77 with Parkinson’s Disease and 39 healthy controls) detected serum proNGF using ELISA in all participants at a very low level, in the range of 0.085–0.122 ng/mL, 10–100 fold lower than detected in our study [23]. Together, these data and our study indicate generally low levels of proNGF in human sera across a variety of conditions. There were no prior data on the levels of proNGF in thyroid biopsy specimens.

The majority of patients with thyroid cancers included in both the serum and needle-rinse studies were diagnosed with the papillary subtype, and it is possible that other subtypes (follicular, medullary) may have different systemic expression patterns of proNGF. However, previous immunohistochemistry data demonstrated that the strongest overexpression of proNGF was in papillary cancers [10], so any positive signal would have been expected in this group. Medullary thyroid cancers, derived from neuro-endocrine parafollicular C-cells, may be more likely to secrete a neurotrophins such as proNGF [24, 25]. However, medullary tumors have established and highly sensitive serum biomarkers: calcitonin and carcino-embryonic antigen [26], and therefore the clinical utility of additional markers may have limited translational value.

Intriguingly, our study observed an association between serum proNGF and hyperthyroidism, which has not previously been described in humans. However, studies in mice have shown that administration of the thyroid hormones T4 or T3 increases synthesis of NGF in mouse submandibular glands and brain [27,28,29,30,31]. Black and colleagues [27] demonstrated increased NGF mRNA production in neonatal mouse salivary glands for 24–72 h following a single intravenous injection of thyroid hormone (triiodothyronine, T3). These previous animal studies and our present investigation suggest a thyroid-hormone regulated transcription of the NGF gene that may account for some of the cases of detectable serum proNGF, although this observation requires validation in a larger cohort of hyperthyroid patients. We hypothesise that the detected proNGF is not of thyroidal origin, as it remained present in the serum of 91% of cases for which a paired post-thyroidectomy sample was available, but rather is likely to be secreted from an alternate site, such as salivary glands [32] under the regulation of thyroid hormone.

Conclusions

In conclusion, these data show that proNGF is not a useful clinical biomarker of thyroid malignancies. From a translational perspective, it is important to report data on both biomarkers that show promises as well as those that are not clinically useful. In addition, the association between proNGF and hyperthyroidism that we have observed warrants further investigation to better understand the molecular and/or functional relationship between proNGF and hyperthyroidism.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Abbreviations

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FNA:

-

Fine needle aspiration

- NGF:

-

Nerve growth factor

- ProNGF:

-

Precursor for nerve growth factor

- QC:

-

Quality control

- TSH:

-

Thyroid stimulating hormone

References

Lim H, Devesa SS, Sosa JA, Check D, Kitahara CM. Trends in thyroid Cancer incidence and mortality in the United States, 1974-2013. JAMA. 2017;317(13):1338–48.

Dean DS, Gharib H. Epidemiology of thyroid nodules. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;22(6):901–11.

Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, Doherty GM, Mandel SJ, Nikiforov YE, Pacini F, Randolph GW, Sawka AM, Schlumberger M, et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid Cancer: the American Thyroid Association guidelines task force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid Cancer. Thyroid. 2016;26(1):1–133.

Ahn HS, Kim HJ, Welch HG. Korea's thyroid-cancer "epidemic"--screening and overdiagnosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(19):1765–7.

Hu Y, Wang H, Chen E, Xu Z, Chen B, Lu G. Candidate microRNAs as biomarkers of thyroid carcinoma: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and experimental validation. Cancer Med. 2016;5(9):2602–14.

Nixon AM, Provatopoulou X, Kalogera E, Zografos GN, Gounaris A. Circulating thyroid cancer biomarkers: current limitations and future prospects. Clin Endocrinol. 2017;87(2):117–26.

Makki FM, Taylor SM, Shahnavaz A, Leslie A, Gallant J, Douglas S, Teh E, Trites J, Bullock M, Inglis K, et al. Serum biomarkers of papillary thyroid cancer. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;42(1):16.

Griffin N, Faulkner S, Jobling P, Hondermarck H. Targeting neurotrophin signaling in cancer: the renaissance. Pharmacol Res. 2018;135:12–7.

Faulkner S, Jobling P, March B, Jiang CC, Hondermarck H. Tumor neurobiology and the war of nerves in Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2019;9(6):702–10.

Faulkner S, Roselli S, Demont Y, Pundavela J, Choquet G, Leissner P, Oldmeadow C, Attia J, Walker MM, Hondermarck H. ProNGF is a potential diagnostic biomarker for thyroid cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:28488–97.

Hondermarck H. Neurotrophins and their receptors in breast cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2012;23(6):357–65.

Levi-Montalcini R. The nerve growth factor: thirty-five years later. Biosci Rep. 1987;7(9):681–99.

Tomellini E, Touil Y, Lagadec C, Julien S, Ostyn P, Ziental-Gelus N, Meignan S, Lengrand J, Adriaenssens E, Polakowska R, et al. Nerve growth factor and proNGF simultaneously promote symmetric self-renewal, quiescence, and epithelial to mesenchymal transition to enlarge the breast cancer stem cell compartment. Stem Cells. 2015;33(2):342–53.

Demont Y, Corbet C, Page A, Ataman-Önal Y, Choquet-Kastylevsky G, Fliniaux I, Le Bourhis X, Toillon R-A, Bradshaw RA, Hondermarck H. Pro-nerve growth factor induces Autocrine stimulation of breast Cancer cell invasion through Tropomyosin-related kinase a (TrkA) and Sortilin protein. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(3):1923–31.

Pundavela J, Demont Y, Jobling P, Lincz LF, Roselli S, Thorne RF, Bond D, Bradshaw RA, Walker MM, Hondermarck H. ProNGF correlates with Gleason score and is a potential driver of nerve infiltration in prostate cancer. Am J Pathol. 2014;184(12):3156–62.

Truzzi F, Marconi A, Lotti R, Dallaglio K, French LE, Hempstead BL, Pincelli C. Neurotrophins and their receptors stimulate melanoma cell proliferation and migration. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128(8):2031–40.

Faulkner S, Jobling P, Rowe CW, Rodrigues Oliveira SM, Roselli S, Thorne RF, Oldmeadow C, Attia J, Jiang CC, Zhang XD, et al. Neurotrophin receptors TrkA, p75(NTR), and Sortilin are increased and targetable in thyroid Cancer. Am J Pathol. 2018;188(1):229–41.

Moon JH, Kim YI, Lim JA, Choi HS, Cho SW, Kim KW, Park HJ, Paeng JC, Park YJ, Yi KH, et al. Thyroglobulin in washout fluid from lymph node fine-needle aspiration biopsy in papillary thyroid cancer: large-scale validation of the cutoff value to determine malignancy and evaluation of discrepant results. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(3):1061–8.

Kudo T, Miyauchi A, Ito Y, Takamura Y, Amino N, Hirokawa M. Diagnosis of medullary thyroid carcinoma by calcitonin measurement in fine-needle aspiration biopsy specimens. Thyroid. 2007;17(7):635–8.

Biosensis. BEK-2226 Human proNGF Rapid ELISA Kit. Adelaide, Australia: Biosensis Pty Ltd; 2015.

Dicou E. High levels of the proNGF peptides LIP1 and LIP2 in the serum and synovial fluid of rheumatoid arthritis patients: evidence for two new cytokines. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;194(1–2):143–6.

Mysona BA, Matragoon S, Stephens M, Mohamed IN, Farooq A, Bartasis ML, Fouda AY, Shanab AY, Espinosa-Heidmann DG, El-Remessy AB. Imbalance of the nerve growth factor and its precursor as a potential biomarker for diabetic retinopathy. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:571456.

Xu X-M, Dong M-X, Feng X, Liu Y, Pan J-X, Jia S-Y, Cao D, Wei Y-D. Decreased serum proNGF concentration in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurol Sci. 2018;39(1):91–6.

Bigazzi M, Revoltella R, Aand SC, Vigneti E. High level of a nerve growth factor in the serum of a patient with medullary carcinoma of the thyroid gland. Clin Endocrinol. 1977;6(2):105–12.

Dicou E, Lee J, Brachet P. Synthesis of nerve growth factor mRNA and precursor protein in the thyroid and parathyroid glands of the rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83(18):7084–8.

Costante G, Meringolo D, Durante C, Bianchi D, Nocera M, Tumino S, Crocetti U, Attard M, Maranghi M, Torlontano M, et al. Predictive value of serum calcitonin levels for preoperative diagnosis of medullary thyroid carcinoma in a cohort of 5817 consecutive patients with thyroid nodules. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(2):450–5.

Black MA, Pope L, Lefebvre FA, Lefebvre YA, Walker P. Thyroid hormones precociously increase nerve growth factor gene expression in the submandibular gland of neonatal mice. Endocrinology. 1992;130(4):2083–90.

Black MA, Lefebvre FA, Pope L, Lefebvre YA, Walker P. Thyroid hormone and androgen regulation of nerve growth factor gene expression in the mouse submandibular gland. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1992;84(1–2):145–54.

Aloe L, Levi-Montalcini R. Comparative studies on testosterone and L-thyroxine effects on the synthesis of nerve growth factor in mouse submaxillary salivary glands. Exp Cell Res. 1980;125(1):15–22.

Walker P, Weichsel ME Jr, Hoath SB, Poland RE, Fisher DA. Effect of thyroxine, testosterone, and corticosterone on nerve growth factor (NGF) and epidermal growth factor (EGF) concentrations in adult female mouse submaxillary gland: dissociation of NGF and EGF responses. Endocrinology. 1981;109(2):582–7.

Walker P, Weil NL, Weichsel ME Jr, Fischer DA. Effect of thyroxine on nerve growth factor concentration in neonatal mouse brain. Life Sci. 1981;28(15–16):1777–87.

Nam JW, Chung JW, Kho HS, Chung SC, Kim YK. Nerve growth factor concentration in human saliva. Oral Dis. 2007;13(2):187–92.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Ms. Rosemary Carroll (Department of Surgery, John Hunter Hospital) with serum collection; Dr. Julie Weigner & Ms. Sharon Ling (NSW Health Pathology, Hunter) with biopsy preparation, and Ms. Catherine Fenwick (Newcastle Endocrinology) for assistance with recruitment.

Funding

This work was supported by a Hunter New England LHD Clinical Research Fellowship, and a Hunter Cancer Research Alliance Pilot Grant and an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship (to CR). None of the funding bodies had any role in the design of the study, or the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CR and HH conceived and conducted the study, analysed the data and drafted the manuscript, with contributions to study design and analysis from JA, and RS. SF, JP and JT contributed to ELISA optimisation. CB, KW and SM contributed to recruitment. CG contributed to interpretation. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was prospectively approved by the Hunter New England Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/16/HNE/247) and all participants provided written informed consent to participate.

Consent for publication

All participants provided written informed consent for study data to be published.

Competing interests

HH holds intellectual property for the use of proNGF as a diagnostic test in cancer. The other authors report nothing to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

(A-E): ProNGF ELISA Validation Experiments – Serum and Rinse. A: Effect of heterophilic antibody blockers (Ab) (BL-003-1000, Biosensis, Australia) on rate of positivity of serum proNGF levels. B: Spike and Recovery Experiments. C: Inter-plate Quality Control Samples D: Linearity of Dilution E: Linearity of Dilution of Biopsy Rinse Diluent.

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Individual patient characteristics for cases with detectable serum proNGF.

Additional file 3: Table S3.

Individual patient characteristics for cases with detectable biopsy proNGF. Age is presented as a range to preserve anonymity.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Rowe, C.W., Faulkner, S., Paul, J.W. et al. The precursor for nerve growth factor (proNGF) is not a serum or biopsy-rinse biomarker for thyroid cancer diagnosis. BMC Endocr Disord 19, 128 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-019-0457-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-019-0457-1