Abstract

Background

Polyandry is commonly maintained by direct benefits in gift-giving species, so females may remate as an adaptive foraging strategy. However, the assumption of a direct benefit fades in mating systems where male gift-giving behaviour has evolved from offering nutritive to worthless (non-nutritive) items. In the spider Paratrechalea ornata, 70% of gifts in nature are worthless. We therefore predicted female receptivity to be independent of hunger in this species. We exposed poorly-fed and well-fed females to multiple males offering nutritive gifts and well-fed females to males offering worthless gifts.

Results

Though the treatments strongly affected fecundity, females of all groups had similar number of matings. This confirms that female receptivity is independent of their nutritional state, i.e. polyandry does not prevail as a foraging strategy.

Conclusions

In the spider Pisaura mirabilis, in which the majority (62%) of gifts in nature are nutritive, female receptivity depends on hunger. We therefore propose that the dependence of female receptivity on hunger state may have evolved in species with predominantly nutritive gifts but is absent in species with predominantly worthless gifts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Evolution and maintenance of polyandry has been extensively studied during the last decades, and so far, costs and benefits have been empirically tested and verified in several species of vertebrates and invertebrates [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. It is known that in polyandrous species selective pressures on males’ sexual traits become more intense the more partners the females mate with and thus the more uncertain paternity is [1]. Females may be interested in access to territories, parental care, food gifts or protection because all these male-provided benefits increase their fecundity and survival, overall enhancing successful reproduction [9,10,11,12]. However, due to different adverse factors resulting in limited food availability or low body condition, males may not be able to provide the goods that females prefer. Instead, they may maximize their success by reducing their costs, e.g. by deception [13, 14]. If females are unable to discriminate such deceptive behaviours, polyandry would be maintained in spite of sexual antagonism resulting in reproductive advantages for males and suboptimal mating rates for females [15].

By mating multiple times females from nuptial gift-giving species can gain direct benefits in the form of food gifts, gathering resources that improve their fitness (i.e. fecundity, hatching success, survival) [10, 16,17,18]. It has been argued that originally nuptial gifts appeared as “paternal investment”, in which nutrients supplied by the gift are used by females to increase the number and/or success of offspring [10, 19, 20]. However, there is also evidence that in some species males can use gifts to manipulate female behaviour [21]. Such is the case in species in which males’ gift-giving behaviour evolved into offering of non-nutritive items, also known as worthless gifts [22,23,24]. The evolution of worthless gifts and the subsequent selection pressures on females to counteract the deception has rarely been studied [25].

The Neotropical gift-giving spider Paratrechalea ornata (Trechaleidae) is exceptional for studying sexual selection in relation to gift content. This is because field data sampled along the reproductive season from three different populations in Uruguay indicate that 70% of nuptial gifts are worthless [26]. Although males can court without a gift, they experience a reduced female acceptance rate, shorter mating duration as well as lower sperm storage in the female spermathecae [26,27,28]. This creates selective pressure on the males to offer nuptial gifts. Males can provide nutritive gifts by capturing an insect prey and wrapping it in silk [29], but when no prey is available, they may wrap inedible items like plant parts, seeds or prey leftovers, in silk to produce worthless gifts [26]. Females are polyandrous [30] but they can only recognize the gift content after they have grabbed the gift and accepted to mate. Mating duration is extremely short (c. 1 min) in this species, and it has been suggested that females are unable to recognize the gift content in such a short time. Hence, this deceptive behaviour allows males to mate as successfully as males with nutritive gifts, i.e. they obtain similar frequencies of acceptances and similar mating durations [26].

Deception by offering worthless gifts has also been described in the Palaearctic spider Pisaura mirabilis with an occurrence of 38% in the field [24]. As most of the gifts in this species are nutritive there is selection on females for remating multiply because it increases their fecundity and the hatching success of their eggs [31]. However, due to mating costs (lowered fecundity and hatching success; reduced hatchling size [31]) females benefit from remating multiply only at suboptimal prey availabilities. With high prey availability the female may meet the nutritional demands at low foraging costs and no mating costs, so that the fecundity benefit for the females of an additional mating is low. This may result in a correlation between female hunger state and receptivity, so that polyandry contributes to the female’s foraging strategy depending negatively on prey availability [31,32,33]. In the case of Paratrechalea ornata, however, with high frequency of worthless gifts there is less/no selection for coupling hunger and receptivity as long as mating costs are non-trivial. Though we do not know the magnitude of mating costs in this species, by comparison with P. mirabilis we expected little or no influence of hunger state on female receptivity. We propose the general hypothesis that, all else equal, female receptivity depends on hunger in mating systems with mostly nutritive gifts but not in mating systems with a majority of worthless gifts. Here, we study the situation in P. ornata and expect a result that contrasts with those already published for P. mirabilis [31,32,33]. Following this prediction we exposed well-fed females of P. ornata to multiple males offering either nutritive or worthless gifts and predicted that females would accept similar number of matings across both gift groups. Thus, females receiving nutritive gifts will acquire more food and most probably achieve higher fitness (i.e. oviposition, fecundity, hatching success) compared to those receiving worthless gifts, but the number of matings should be independent of the nutritional state of the females. If the hypothesis is true, then also females under extremely limited foraging opportunities should not significantly increase the overall number of matings in order to access more food. Thus, we also exposed poorly fed females to multiple males offering nutritive gifts. These females were expected to obtain lower fecundity than the well-fed females, as they would need to use some of the food to compensate for their low condition. Fitness measures of females under limited foraging opportunities will ultimately strengthen our understanding of the reproductive consequences of receiving worthless gifts.

Methods

We collected juveniles, subadults and adults at night during the reproductive season of 2013 and 2014 from Santa Lucía River, Paso del Molino, Lavalleja, Uruguay (34°16′40.10″ S, 55° 14′00.80″W). Immature individuals were placed in a climate room at 25.02 °C (± 0.11 SE) to accelerate their development. We provided water in a cotton wool daily and twice a week we fed them with fruitflies (Drosophila sp.). Once individuals reached adulthood we transferred them to the experimental room at an average temperature of 21.33 °C (± 0.16 SE). Here they were subjected to the same feeding regimen during the next 15 days. With this procedure we ensured that all spiders were sexually mature and the females receptive [34]. After this period, we started experiments where we continued feeding adult males twice a week, while females were maintained in two feeding groups until oviposition: well fed and poorly fed. We fed well-fed females with 10 fruitflies every day, while poorly fed females only ate from gifts offered by males. We verified that as consequence of the food received via matings (1 fly gift per mating) and the daily feeding regimen (10 fruitflies per day) in relation to the number of experiments, the total food events (number of food occurrence: gifts + fruitflies/ number of experiments) by females was different among groups (mean ± SE): Well fed-Nutritive gift (2.59 ± 0.05) > Well fed-Worthless gift (1.97 ± 0.01) > Poorly fed- Nutritive gift (0.58 ± 0.04) (GLM (p): X 2 2, 63 = 438.93, p < 0.0001). We carried out mating experiments with all groups during both years. We used only unmated females and we also planned to use only unmated males, but due to the unexpectedly high number of matings per female, we would have needed more than 800 males in total, a sample size impossible to reach with this spider species. Therefore, we also used adult males from the field and sometimes males were used more than once. Females and males were randomly assigned to each of the three experimental groups, eliminating any possible effect of individual variation on the between groups comparison. We verified that repetition of males occurred similarly among the three groups, and most females mated equally with different males (90% approx; F2, 63 = 2.14, p = 0.13).

Multiple matings were obtained by exposing different groups of females to males with different types of gift every two days until eggsac construction. With this procedure, we allowed females to encounter numerous males carrying silk wrapped gifts throughout the reproductive period, and thus they had many mating opportunities before constructing the first eggsac. Following a previous protocol [26, 28], one experimental group was the Well fed-Nutritive gift group (N = 21), where well-fed females were exposed to males offering nutritive gifts, which consisted of a recently captured housefly (Musca domestica). A second group was the Well fed-Worthless gift group (N = 22), where well-fed females were exposed to males offering worthless gifts consisting of the exuviae of a mealworm (Tenebrio molitor larva). A third consisted of poorly fed females which had not received fruitflies and could feed only from nutritive fly gifts offered by males (Poorly fed-Nutritive gift, N = 21). Initially, we wanted an experimental design, which also included poorly fed females exposed to males offering worthless gifts. However, in preliminary assays these females ended up in very bad body condition and failed to accept matings and construct eggsacs. Hence, due to ethics issues related to animal care we did not carry out experiments with this group. Experimental protocols were carried out in accordance with the general approved guidelines for animal behaviour.

We performed the experiments in transparent plastic jars (15 cm diameter × 9 cm height) in which we simulated natural conditions by covering the bottom with pebbles and water. We placed females in the experimental jars 24 h before experiments, allowing them to habituate and deposit silk that stimulate male courtship and silk wrapping of the gift [35]. Trials followed a fixed procedure: first we enclosed the female inside a glass vial (3 cm diameter and 8 cm height) in the experimental jar. Subsequently, we placed the male in the jar with female silk, allowing him 20 min to detect female sex pheromones and start wrapping the gift material (a live housefly given to the male or exuviae of a mealworm placed in the jar). If the male did not wrap the fly or exuviae we allowed physical contact with the female but not the mating, as we simulated female rejection by pushing her away with a paintbrush. Female rejection stimulates silk wrapping of the gift [27]. We then enclosed the female again and left the male on the silk for another 20 min; if the male still did not start silk wrapping we replaced him with another male. Up to three males were tested at each mating session if necessary. This procedure avoided potential individual incompatibilities and secured that all males offered wrapped gifts. When the male had a wrapped gift we finally released the female and allowed contact between the sexes and mating. We registered all behaviours during 30 min if no mating occurred or until 5 min after the mating was finished.

The behavioural response variables included: frequency of mating, latency of female acceptance, mating duration, sexual cannibalism and gift stealing (i.e. if females grasped the gift and ran away without mating). Latency of acceptance was considered only when mating occurred and was measured from the moment we allowed contact between the sexes and until the female grasped the gift. Mating duration was calculated from the total number of matings of each female and measured as the total duration of all pedipalp insertions, each one lasting from intromission until disengagement. The frequency of sexual cannibalism and gift stealing events was recorded for each female, including several cases by the same female.

The fitness response variables included: latency of oviposition, fecundity and hatching success. We calculated latency of oviposition as the days taken by females to construct the eggsac since the first accepted mating. Once females constructed the eggsac, we placed them under light bulbs (60 W) in order to increase luminosity and temperature (mean ± SE: 28.47 ± 0.14 °C) for three hours at midday. This procedure improves spiderling emergence and has previously been used with other spider species [24, 36]. We provided water and fed females with fruitflies daily. Once spiderlings emerged we counted them and opened the eggsac to also record the unhatched eggs. Fecundity was calculated as the sum of spiderlings and unhatched eggs, and hatching success as the proportion of spiderlings from the total fecundity. If females abandoned the eggsac before the spiderlings emerged, we opened it and counted the number of unhatched eggs inside; in nine cases this was not possible because the females had eaten the eggsac.

Statistical analyses

We performed statistical analyses using free platform R [37]. Considering our experimental design, we performed Generalized lineal mixed models (GLMM), with response variables being mating and fitness parameters, experimental groups used as fixed effects, female ID as a random effect, and female age as covariate. This considered repeated measures structure within females for fitness parameters controlling for the effect of female ID and age; while also a female effect random structure for the different levels of mating parameters. We explored the distribution of the raw data for each variable to account for the potential error family distribution [38]. We examined using a GLMM (Binomial) frequency of mating, cannibalism, gift stealing and hatching success. Latency of oviposition was analysed using Generalized least square (GLS), while fecundity was analysed using GLMM (Poisson). We performed LMM (LogNormal) to analyse effects on latency of acceptance and mating duration. All the models were validated through the exploration of residual errors with graphical tools [38]. Raw data are presented as Additional file 1.

Results

Mating effects

The frequency of accepted matings was not significantly different among the females of the three experimental groups (Table 1, Fig. 1). Latency of acceptance and mating duration were also similar showing no statistical differences among the groups (Tables 1 and 2).

Number of matings from well-fed females receiving fly gifts (Well fed-Nutritive gift, N = 21), well-fed females receiving worthless gifts (Well fed-Worthless gift, N = 22) and poorly fed females receiving fly gifts (Poorly fed-Nutritive gift, N = 21). Data are given as means ± standard error; different letters indicate statistical differences among groups

We observed (but did not quantify) that poorly fed females were less active, i.e. walking and contacting males less often during courtship and mating than well-fed females.

Few females (4% overall) attacked and cannibalized males in the three groups; poorly fed females cannibalized more males than females in the other groups (Table 1; Table 2). Some females stole the gift from courting males, meaning that they accepted the gift but ran away without mating. The occurrence of gift stealing showed differences among groups as follows: Poorly fed-Nutritive gift = Well fed-Nutritive gift > Well fed-Worthless gift (Table 1; Fig. 2).

Number of gift stealing performed by females during courtship from well-fed females receiving fly gifts (Well fed-Nutritive gift, N = 21), well-fed females receiving worthless gifts (Well fed-Worthless gift, N = 22) and poorly fed females receiving fly gifts (Poorly fed-Nutritive gift, N = 21). Data are given as mean ± standard error; different letters indicate statistical differences among groups

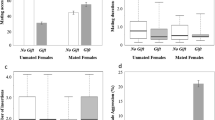

Fitness effects

Twenty-one well-fed females receiving fly gifts, 22 well-fed females receiving worthless gifts and 21 poorly fed females receiving fly gifts constructed an eggsac. Latency of oviposition was statistically different among the three groups (Table 3). Well-fed females receiving fly gifts oviposited earlier than females in the other groups (Fig. 3). Also, well-fed females receiving fly gifts had elevated fecundity (spiderlings + unhatched eggs) compared to females in the other groups (Table 3; Fig. 4a). Number of spiderlings was larger in the group of well-fed females receiving fly gifts compared to the other two groups, but with no statistical differences (Table 3; Fig. 4b). Hatching success (spiderlings / fecundity) did not differ among groups (Table 3).

Latency of oviposition from well-fed females receiving fly gifts (Well fed-Nutritive gift, N = 21), well-fed females receiving worthless gifts (Well fed-Worthless gift, N = 22) and poorly fed females receiving fly gifts (Poorly fed-Nutritive gift, N = 21). Data are given as mean ± standard error; different letters indicate statistical differences among groups

a Fecundity (hatched eggs + unhatched eggs) and b Number of spiderlings (hatched eggs), from well-fed females receiving fly gifts (Well fed-Nutritive gift, N Fecundity = 18 and N No. spiderlings = 17), well-fed females receiving worthless gifts (Well fed-Worthless gift, N Fecundity = 19 and N No. spiderlings = 19) and poorly fed females receiving fly gifts (Poorly fed-Nutritive gift, N Fecundity = 18 and N No. spiderlings = 17 respectively). Data are given as mean ± standard error; different letters indicate statistical differences among groups

Discussion

It is known that females from nuptial gift-giving species often mate with multiple males, trading sex for food gifts and consequently gaining fitness benefits [16]. They can even modulate their mating rate based on what is optimal under certain ecological conditions [16, 31, 39]. For instance, empirical examples have also shown that when food is scarce, polyandrous females can drastically increase the number of matings [31, 39, 40], and even compete for potential mates that offer food resources in the form of gifts [41,42,43,44]. But, in mating systems with high frequency of deception by worthless gifts, like in the spider P. ornata, little or no influence of hunger state on female receptivity may be predicted. Our results showed that all female groups had similar mating rate irrespective of feeding condition, and even poorly fed females did not significantly increase the number of matings with males offering nutritive gifts. Thus, our results support the hypothesis of behavioural differences between mating systems that differ in the relative frequency of nutritive and worthless gifts. In the gift-giving spider P. mirabilis, worthless gifts occur at low frequency (38%) in the field [24] and females in low nutritional condition double their mating rate compare to those in high condition [31,32,33]. In such a mating system, females gain food from multiple matings/gifts, resulting in an increase of their fitness [31]. In the case of P. ornata, we did not find support for the hypothesis of polyandry as an adaptive foraging strategy. We do not have solid information to understand how mating behaviour has changed over evolutionary time in this species, but one possibility is that control of female receptivity may have changed due to evolution of male deception. As both P. ornata and P. mirabilis are polyandrous it seems possible that polyandry is maintained by other reasons than direct benefits. Alternatively, it can be argued that the lack of association between female hunger state and receptivity may be mediated by low food availability in the population, which also leads to high frequency of worthless gifts. In this scenario, high female mating activity may have been favoured under food restricted conditions, so that the more they mate, the higher the chances of consuming at least a few nutritive gifts. This requires, however, that mating costs in P. ornata are much lower than in P. mirabilis. The much shorter mating duration (c. 1 min against c. 70 min) make this a realistic possibility. Nevertheless, we would need further studies evaluating costs of mating in this species, as well as food availably and body condition in nature.

Polyandry may be maintained by indirect benefits interacting with direct benefits [45, 46]. If in P. ornata the nuptial gift is a reliable signal of positive male attributes, then females may gain genetic benefits from accepting males offering gifts even if these are worthless. For instance, beyond gift content, gift-giving males usually invest in silk wrapping which involves costs such as time and energy, and those in poor body condition are usually limited in this behaviour [36, 47]. Thus, silk wrapping represents an honest indicator of some male attributes and quality, and females would benefit from mating with “good wrappers” [48, 49].

Due to the females’ inability to recognize the gift content before accepting the mating [26], there is a high risk of being deceived by courting males. It would be advantageous for females to recognize the gift content before mating, as by accepting only males with nutritive gifts females can significantly increase their reproductive outcome. We found that those receiving the highest nutritional benefits oviposited earlier and obtained higher fecundity than the others. By constructing the first eggsac early these females will probably have more eggsacs and therefore, more offspring along the reproductive season. Effects of food gifts on oviposition have been suggested before in this and another gift-giving spider [31, 45], however, these studies were unable to disentangle the effects of food and sperm. Here, we can discard an effect of sperm as all groups had similar mating number and mating duration, whereas differences in food intake lead to differences in the latency of oviposition. Thus, the variation in female fitness parameters (oviposition and fecundity) must be explained mainly by the variation in the amount food consumed. Effects of from nuptial gifts on fecundity and hatching success are well-known in some insects [10, 16]. When females receive nutritive gifts their net food intake increases and they can use it in their own metabolism as well as in egg production [50, 51]. Preliminary results verify that the food acquired from the nuptial gifts can be distributed into somatic and reproductive tissues in P. ornata, mostly incorporated into eggs and silk of the eggsac (Costa-Schmidt unpublished data).

Indeed, in our experiments females receiving worthless gifts experienced a reduction in fitness like females limited in their foraging opportunities. Under this scenario, they would need to balance the potential costs of mating under limited food supply. Then, one potential tactic that females can perform to compensate these costs and increase their food consumption is to reject the mating and cannibalize the male [52, 53]. Although cannibalism occurred in low proportion in all groups, we found that poorly fed females cannibalized males more frequently than females from the other groups. Another possible female tactic to avoid mating costs is to steal gifts from males during courtship. We found that poorly fed females stole the gifts more often compared to the well-fed group receiving worthless gifts. However, well-fed females receiving nutritive gifts also presented high percentage of gifts stealing (similar to poorly fed females) suggesting that it may be a matter of gift type. This is not necessarily an indication that females recognize the gift content during courtship, because it can also be a consequence of the silk wrapping of the gift. It has been suggested that the silk helps males to better grasp and keep control on the gift [54, 55]; further experiments are needed to understand whether males invest differently in silk depending on gift type.

Conclusions

This study is the first to discuss whether male deception may influence female receptivity and mating rate in gift-giving species. In the particular case of the spider P. ornata females can still acquire fitness advantages from nutritive gifts. However, we conclude that polyandry does not seem to prevail as a foraging strategy in P. ornata, and suggest that the dependence of female receptivity on hunger in gift-giving species depends on the level of male deception. To verify this, future studies using less extreme feeding conditions would need to focus on whether females can (before mating) evaluate and respond differentially to nutritive vs. worthless gifts according to their nutritional state.

References

Kvarnemo C, Simmons LW. Polyandry as a mediator of sexual selection before and after mating. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci. 2013;368:20120042. Available from: http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/368/1613/20120042.short#sec-12

Watson PJ, Stallmann RR, Arnqvist G. Sexual conflict and the energetic costs of mating and mate choice in water striders. Am Nat. 1998;151:46–58. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18811423

Zeh JA, Zeh DW. Reproductive mode and the genetic benefits of polyandry. Anim Behav [Internet]. 2001;61:1051–63. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0003347200917056

Simmons LW. The evolution of polyandry: sperm competition, sperm selection, and offspring viability. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2005;366:125–46. Available from: http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.36.102403.112501

Snook RR. The evolution of polyandry. In: Shuker DM, Simmons LW, editors. Evol. insect mating Syst. Oxford University Press; 2014. p. 159–180. Available from: http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199678020.001.0001/acprof-9780199678020-chapter-9.

Rowe L, Arnqvist G, Sih A, Krupa JJ. Sexual conflict and the evolutionary ecology of mating patterns: water striders as a model system. Trends Ecol Evol. 1994;9:289–93. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0169534794900329

Thrall PH, Antonovics J, Dobson AP. Sexually transmitted diseases in polygynous mating systems: prevalence and impact on reproductive success. Proc Biol Sci. 2000;267:1555–63. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11007332

Jennions MD, Petrie M. Why do females mate multiply? A review of the genetic benefits. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2000;75:21–64. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10740892

Forsgrent E. Female sand gobies prefer good fathers over dominant males. Proc R Soc B. 1997;264:1283–6. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1688594/

Vahed K. The function of nuptial feeding in insects: review of empirical studies. Biol Rev. 1998;73:43–78. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1469-185X.1997.tb00025.x/abstract

Alatalo RV, Lundberg A, Glynn C. Female pied flycatchers choose territory quality and not male characteristics. Nature. 1986;323:152–3. Available from: http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/323152a0

Slatyer RA, Jennions MD, Backwell PRY. Polyandry occurs because females initially trade sex for protection. Anim Behav. 2012;83:1203–6. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0003347212000887

Gross MR. Alternative reproductive strategies and tactics: diversity within sexes. Trends Ecol Evol. 1996;11:92–8. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0169534796810500

Neff BD, Svensson EI. Polyandry and alternative mating tactics. Philos Trans R Soc London B Biol Sci. 2013;368:20120045. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3576579/

Arnqvist G, Rowe L. Sexual conflict. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press; 2005.

Arnqvist G, Nilsson T. The evolution of polyandry: multiple mating and female fitness in insects. Anim Behav. 2000;60:145–64. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10973716

Gwynne DT. Sexual conflict over nuptial gifts in insects. Annu Rev Entomol. 2008;53:83–101. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17680720

Lewis SM, South A. The evolution of animal nuptial gifts. Adv Study Behav. 2012;44:53–97. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780123942883000022

Thornhill R. Sexual selection and paternal investment in insects. Am Nat. 1976;110:153–63. Available from: http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/283055?journalCode=an

Boggs CL. Male nuptial gifts: phenotypic consequences and evolutionary implications. Insect Reprod. 1995:215–42.

Lewis SM, Vahed K, Koene JM, Engqvist L, Bussière LF, Perry JC, et al. Emerging issues in the evolution of animal nuptial gifts. Biol Lett. 2014;10:20140336. Available from: http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/10/7/20140336

Preston-Mafham KG. Courtship and mating in Empis (Xanthempis) trigramma Meig., E. tesselata F., and E. (Polyblepharis) opaca F. (Diptera: Empididae) and the possible implication of “cheating” behavior. J Zool. 1999;247:239–46. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1999.tb00987.x/abstract

LeBas NR, Hoffman LR. The evolution of cheat, worthless nuptial gifts. Curr Biol. 2005;15:64–7. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982204010218

Albo MJ, Winther G, Tuni C, Toft S, Bilde T. Worthless donations: male deception and female counter play in a nuptial gift-giving spider. BMC Evol Biol. 2011;11:329. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/11/329

Ghislandi PG, Albo MJ, Tuni C, Bilde T. Evolution of deceit by worthless donations in a nuptial gift-giving spider. Curr Zool. 2014;60:43–51. Available from: http://www.currentzoology.org/temp/%7B2486E4AC-D55C-48BE-BB92-CA1E3DDFDF87%7D.pdf

Albo MJ, Melo-González V, Carballo M, Baldenegro F, Trillo MC, Costa FG. Evolution of worthless gifts is favoured by male condition and prey access in spiders. Anim Behav. 2014;92:25–31. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0003347214001456

Albo MJ, Costa FG. Nuptial gift-giving behaviour and male mating effort in the Neotropical spider Paratrechalea ornata (Trechaleidae). Anim Behav. 2010;79:1031–6. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0003347210000400

Albo MJ, Peretti AV. Worthless and nutritive nuptial gifts: mating duration, sperm stored and potential female decisions in spiders. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129453. Available from: http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0129453

Costa-Schmidt LE, Carico JE, De Araújo AM. Nuptial gifts and sexual behavior in two species of spider (Araneae, Trechaleidae, Paratrechalea). Naturwissenschaften. 2008;95:731–9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18414824

Klein AL, Trillo MC, Costa FG, Albo MJ. Nuptial gift size, mating duration and remating success in the spider Paratrechalea ornata. Ethol Ecol Evol. 2014;26:29–39. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03949370.2013.850452

Toft S, Albo MJ. Optimal numbers of matings: the conditional balance between benefits and costs of mating for females of a nuptial gift-giving spider. J Evol Biol. 2015;28:457–67. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25580948

Bilde T, Tuni C, Elsayed R, Pekar S, Toft S. Nuptial gifts of male spiders: sensory exploitation of the female’s maternal care instinct or foraging motivation? Anim Behav. 2007;73:267–73. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0003347206004027

Prokop P, Maxwell MR. Female feeding regime and polyandry in the nuptially feeding nursery web spider, Pisaura mirabilis. Naturwissenschaften. 2009;96:259–65. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19050843

Klein AL, Trillo MC, Albo MJ. Sexual receptivity varies according to female age in a Neotropical nuptial gift-giving spider. J Arachnol. 2012;40:138–40. Available from: http://www.americanarachnology.org/JoA_free/JoA_v40_n1/arac-40-1-138.pdf

Albo MJ, Costa-Schmidt LE, Costa FG. To feed or to wrap? Female silk cues elicit male nuptial gift construction in a semiaquatic trechaleid spider. J Zool. 2009;277:284–90. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1469-7998.2008.00539.x/abstract

Albo MJ, Toft S, Bilde T. Female spiders ignore condition-dependent information from nuptial gift wrapping when choosing mates. Anim Behav. 2012;84:907–12. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0003347212003223

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2013; Available from: http://www.r-project.org/.

Zuur AF, Ieno EN, Elphick CS. A protocol for data exploration to avoid common statistical problems. Methods Ecol. Evol. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2010 [cited 2017 9];1:3–14. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.2041-210X.2009.00001.x.

Boulton RA, Shuker DM. The costs and benefits of multiple mating in a mostly monandrous wasp. Evolution (N Y). 2015;69:939–49. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/evo.12636

Judge KA, De Luca PA, Morris GK. Food limitation causes female haglids to mate more often. Can J Zool. 2011;89:992–8. Available from: http://www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/abs/10.1139/z11-078

Gwynne DT. Sexual difference theory: mormon crickets show role reversal in mate choice. Science. 1981;213:779–80. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17834586

Gwynne DT. Courtship feeding increases female reproductive success in bushcrickets. Nature. 1984;307:361–3. Available from: http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/307361a0

Gwynne DT. Testing parental investment and the control of sexual selection in katydids: the operational sex ratio. Am Nat. 1990;136:474–84. Available from: http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/285108

Simmons LW, Baley WJ. Resource influenced sex roles of Zaprochiline tettigoniids (Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae). Evolution (N. Y). 1990;44:1853–68. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2409513?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

Tuni C, Albo MJ, Bilde T. Polyandrous females acquire indirect benefits in a nuptial feeding species. J Evol Biol. 2013;26:1307–16. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/jeb.12137

Engqvist L. Females benefit from mating with different males in the scorpionfly Panorpa cognata. Behav Ecol. 2006;17:435–40. Available from: http://beheco.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/doi/10.1093/beheco/arj046

Trillo MC, Melo-González V, Albo MJ. Silk wrapping of nuptial gifts as visual signal for female attraction in a crepuscular spider. Naturwissenschaften. 2014;101:123–30. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24424786

Zahavi A. Mate selection-a selection for a handicap. J Theor Biol. 1975;53:205–14. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0022519375901113

Kokko H, Brooks RC, Jennions MD, Morley J. The evolution of mate choice and mating biases. Proc Biol Sci. 2003;270:653–64. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1691281/

Simmons LW, Gwynne DT. Reproductive investment in bushcrickets: the allocation of male and female nutrients to offspring. Proc R Soc B. 1993;252:1–5. Available from: http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/252/1333/1

Voigt CC, Kretzschmar AS, Speakman JR, Lehmann GUC. Female bushcrikets fuel their metabolism with male nuptial gifts. Biol Lett. 2008;4:476–8. Available from: http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/4/5/476

Wise DH. Cannibalism, food limitation, intraspecific competition, and the regulation of spider populations. Annu Rev Entomol. 2006;51:441–65. Available from: http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.ento.51.110104.150947

Rabaneda-Bueno R, Rodríguez-Gironés MÁ, Aguado-de-la-Paz S, Fernández-Montraveta C, De Mas E, Wise DH, et al. Sexual cannibalism: high incidence in a natural population with benefits to females. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3484. Available from: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0003484

Stålhandske P. Nuptial gift in the spider Pisaura mirabilis maintained by sexual selection. Behav Ecol. 2001;12:691–7. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/beheco/article/12/6/691/462596/Nuptial-gift-in-the-spider-Pisaura-mirabilis

Andersen T, Bollerup K, Toft S, Bilde T. Why do males of the spider Pisaura mirabilis wrap their nuptial gifts in silk: female preference or male control? Ethology. 2008;114:775–81. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1439-0310.2008.01529.x/abstract

Acknowledgments

We thank Sebastian Fierro, Valentina Melo-González, and Mariana Trillo, for their help in field collections; Laura Montes de Oca for the help in spider maintenance. We thank Fernando G. Costa, Macarena González, Trine Bilde, Tommaso Pizzari, Paco Garcia-Gonzalez and Mariela Herberstein for discussions and fruitful comments on the first draft. We are especially indebted with Søren Toft for his valuable advice on further versions of the draft and language revision.

Funding

MJ Albo was supported by the National Research System-ANII, Uruguay.

Availability of data and materials

Raw data is presented as Additional file 1.

Competing interests

All authors declare no competing financial interests in relation to this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Raw data. (PDF 197 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Pandulli-Alonso, I., Quaglia, A. & Albo, M.J. Females of a gift-giving spider do not trade sex for food gifts: a consequence of male deception?. BMC Evol Biol 17, 112 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-017-0953-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-017-0953-8