Abstract

Background

Mutations in the CHK2 gene at chromosome 22q12.1 have been reported in families with Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Chk2 is an effector kinase that is activated in response to DNA damage and is involved in cell-cycle pathways and p53 pathways.

Methods

We screened 139 breast tumors for loss of heterozygosity at chromosome 22q, using seven microsatellite markers, and screened 119 breast tumors with single-strand conformation polymorphism and DNA sequencing for mutations in the CHK2 gene.

Results

Seventy-four of 139 sporadic breast tumors (53%) show loss of heterozygosity with at least one marker. These samples and 45 tumors from individuals carrying the BRCA2 999del5 mutation were screened for mutations in the CHK2 gene. In addition to putative polymorphic regions in short mononucleotide repeats in a non-coding exon and intron 2, a germ line variant (T59K) in the first coding exon was detected. On screening 1172 cancer patients for the T59K sequence variant, it was detected in a total of four breast-cancer patients, two colon-cancer patients, one stomach-cancer patient and one ovary-cancer patient, but not in 452 healthy individuals. A tumor-specific 5' splice site mutation at site +3 in intron 8 (TTgt [a → c]atg) was also detected.

Conclusion

We conclude that somatic CHK2 mutations are rare in breast cancer, but our results suggest a tumor suppressor function for CHK2 in a small proportion of breast tumors. Furthermore, our results suggest that the T59K CHK2 sequence variant is a low-penetrance allele with respect to tumor growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chk2 (Cds1) is a protein kinase that is involved in cell-cycle checkpoint control by phosphorylating Cdc25 phosphatases, which subsequently results in their inhibition (i.e. degradation or export from the nucleus) [1–4]. Other substrates of Chk2 are p53 and Brca1, which are involved in cell-cycle control, apoptosis, and DNA repair [4–7]. The serine 20 of p53 is phosphorylated by Chk2, and thereby interrupts the binding of p53 to Mdm2 and interrupts p53 ubiquitination, resulting in greater stability of p53 [8]. Chk2 is activated on DNA damage by phosphorylation signaling from the Atm kinase [8–13].

Germ line mutations have been detected in the TP53 and CHK2 genes in patients with Li-Fraumeni syndrome [14–16]. These mutated forms of the Chk2 may have disabilities in protein-protein interactions and in being phosphorylated by Atm [17]. Characteristic tumor types in patients with Li-Fraumeni syndrome are breast cancer, sarcoma, brain carcinoma and adrenal cortex carcinoma, and multiple primary tumors can be observed in the same individuals. There are few reports on somatic mutations of CHK2 in tumors, but mutations have been found in a colon carcinoma cell line and in a case of primary small-cell lung cancer, lymphoma and myelodysplastic syndrome, respectively [14, 18–20]. We used microsatellite markers to analyse the loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at chromosome region 22q, where the CHK2 gene is located, and screened breast and other tumors for mutations in the CHK2 gene.

Materials and methods

Primary breast carcinoma tissue was obtained on the day of surgery. Blood samples from the patients were collected in EDTA and, if not processed immediately, tumor and blood were quick-frozen at -70°C. LOH at chromosome 22q was analysed using seven microsatellite markers on 139 sporadic breast tumors. DNA was analysed by PCR primers that amplify markers D22S277, D22S283, D22S1177, D22S272, D22S423, D22S1179 and D22S282. These markers map telomeric to CHK2 (at position 25,750 kb), or at positions 32,830 kb, 33,300 kb, 33,800 kb, 35,600 kb, 36,900 kb, 40,100 kb and 40,350 kb, respectively.

DNA samples (25 ng) were subjected to PCR analysis in a total volume of 25 μl using DynaZyme™ polymerase (Finnzymes Oy, Espoo, Finland), in 120 μM of each deoxynucleotide triphosphate and 0.24 μM primers. After 5 min of denaturation at 94°C, samples were subjected to 35 cycles of amplification, consisting of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 55°C and 1 min at 72°C. The PCR products were denatured in formamide buffer, separated on 6.5% polyacrylamide denaturing gels, and transferred to a Hybond-N+ nylon membrane (Amersham, Aylesbury, UK). Hybridisation of a peroxidase-labeled probe to the PCR products was visualised using the enhanced chemiluminescence labeling method (ECL kit; Amersham).

LOH was evaluated visually by comparing the intensity of alleles from normal and tumor DNA. The absence or decrease in the intensity of one allele relative to the other was considered as LOH. Tumor samples were scored for LOH at chromosome 22q if at least one informative marker showed LOH. One sample that was homozygous for all tested markers was excluded from the study, while other samples tested heterozygous with two to seven markers.

Sporadic tumors (BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers were excluded) showing LOH at chromosome 22q (74 cases) and 45 breast tumors from carriers of the BRCA2 999del5 mutation [21], not analysed for LOH at 22q, were analysed with single-strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP) and DNA sequencing, using 17 primers for all of the 15 exons of the CHK2 gene. The set of BRCA2 samples was screened to address the possibility that germ line variants could modify BRCA2 risk. The primers were ordered from TAG Copenhagen A/S and information on them is presented in Table 1. The SSCP and DNA sequencing conditions were as described earlier [22].

An additional 1098 tumors of various origins were analysed for the detected T59K sequence variant using the primers from exon 2 and DNA sequencing. RNA was isolated from a tumor showing a splice site mutation and analysed with RT-PCR using primers from exon 7 (forward, 5'-CCCAGCTCTCAATGTTGAAACAG-3') and exon 9 (reverse, 5'-CTGCACAGCCAAGAGCATCTGG-3'). Abnormally sized PCR products were cut from 4% agarose gels and DNA sequenced.

The chi-squared test and Fisher's exact test were used to compare differences of the frequency of sequence variants, between controls, individuals with sporadic breast cancer and individuals with breast cancer carrying the BRCA2 999del5 germ line mutation. The research plan was approved by the National Bioethics Committee.

Results

Seventy-four out of 139 (53%) sporadic breast tumors were detected with LOH at chromosome 22q. Only 11 (16%) of the tumors with 22q LOH showed an almost complete loss of the alleles, while other tumors showed less decrease in μ allele intensity, presumably due to contamination of DNA from non-malignant cells. To evaluate whether CHK2 sequence variants could have modifying effects on the phenotype of BRCA2 mutation carriers, these 74 samples and 45 breast tumors from individuals carrying the BRCA2 999del5 mutation were screened for mutations in the CHK2 gene using SSCP and DNA sequencing.

Five sequence variants were detected: four in the group of 74 sporadic tumors and three in the BRCA2 999del5 group, with two variants common to both groups (Tables 2 and 3). Four of these five sequence variants were also detected in the blood of the patients, indicating a germ line variant, and one mutation was tumor specific, a +3TTgt(a → c)agt in the 5' splice site of intron 8, detected in the group of sporadic breast cancer. This somatic mutation was detected in the tumor of an individual diagnosed with breast cancer at the age of 45 years. LOH at 22q in this tumor was evident from the microsatellite marker analysis.

This position in the splice site at the exon 8–intron 8 boundary does not include the part with the highest conservation, but we analysed the RNA from the tumor to see whether splicing was altered. RT-PCR analysis of RNA from this tumor showed one extra band of lower molecular weight and one band of higher molecular weight than the wild-type transcript, not detected in five nonmalignant and five breast cancer tissues (data not shown). DNA sequencing of the RT-PCR product of the smaller sized transcript showed that the exon 8 sequence was missing.

One of the sequence variants was a clear polymorphism of A → G at nucleotide 252, not affecting the corresponding codon 84 for glutamic acid. We also detected a sequence variant in a non-coding exon of the CHK2 gene, a deletion of a thymine. This occurred in a short stretch of mononucleotide repeats of four thymines. An additional sequence variant was detected in intron 2, an insertion of an adenine in a mononucleotide repeat of five adenines. A missense mutation at codon 59 was also detected, which substituted lysine for threonine.

The frequency of these sequence variants was estimated in individuals without previous diagnosis of cancer, in individuals with sporadic breast cancer, and in individuals with breast cancer carrying the BRCA2 999del5 mutation (Table 3). Chi-squared analysis and Fisher's exact tests did not result in significant difference between the three groups for any of the sequence variants.

The only variant allele not appearing in normal control was the T59K mutation, and this was analysed further in additional controls (in total, 452 individuals) and in individuals diagnosed with cancer in the breast and other tissues (in total, 1172 individuals diagnosed with cancer) (Table 4). The T59K sequence variant was found in additional patients with cancer of the breast (four individuals, one thereof bilateral), cancer of the colon and ovary (one individual), cancer of the colon (one individual), and cancer of the stomach (one individual). All individuals who were detected with the CHK2 T59K mutation in this screening are females.

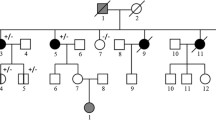

Four of the CHK2 T59K carriers were found to be members of two cancer families. One of the two individuals with colorectal cancer is a sister of the individual with gastric cancer. A third member of this family (a nephew of the two aforementioned cases) also developed colon cancer, but was not a carrier of the CHK2 T59K sequence variant. However, a distant relative with prostate cancer was a carrier of the T59K sequence variant.

Two of the breast-cancer cases (diagnosed at 29 years and 45 years, respectively) were first cousins in a previously reported cancer family [23]. The third cancer case in this family (stomach cancer diagnosed at the age of 55 years and thyroid cancer diagnosed at the age of 58 years in the same individual), a brother of the breast-cancer case diagnosed at age 45 years, is a T59K carrier, but two individuals within this family (with breast cancer and thyroid cancer, respectively) were not T59K carriers. In addition, six healthy individuals of this family did not carry the T59K sequence variant. The two breast-cancer cases with the T59K sequence variant, but no obvious family history of cancer, were diagnosed at 83 years (a bilateral case) and 42 years of age, respectively.

In summary, the CHK2 T59K sequence variant was detected in seven individuals by the screening (including the original carrier from Table 2) and in an additional two individuals in the family analysis, producing a total of nine individuals. Three out of these nine individuals were diagnosed with two tumors (i.e. in total, 12 tumors in nine individuals). Eleven out of the 12 tumors were available for LOH analysis at chromosome 22q, using markers D22S277, D22S1177, D22S272, D22S423 and D221179. Eight of these 11 tumors showed LOH with at least one marker. The three tumors not showing LOH derived from breast cancer (an individual with bilateral disease had LOH at chromosome 22q in only one of the two primary tumors).

Discussion

This screening of a large number of tumor samples suggests that CHK2 gene inactivation does not play a major role in the pathogenesis of cancer growth. We identified a somatic mutation at a splice site in one tumor sample, resulting in abnormal splicing of the gene, in an individual diagnosed with breast cancer at the age of 45 years. The wild-type copy of the CHK2 gene was lost in this individual, suggesting a typical two-hit mechanism of a tumor suppressor gene.

Only one of the four detected germ line variants affects the Chk2 protein sequence, by substituting lysine for threonine at amino acid position 59. This region of the protein is poorly characterised and the functional aspects of the threonine in this position are unclear. This position is close to an Atm phosphorylation site at T68, but there is no evidence so far for a phosphorylation at T59 [9, 13].

The T59K sequence variant is not likely to be highly penetrant with respect to tumor growth. Seven of the nine individuals with the T59K sequence variant were diagnosed with more than one primary tumor and/or are members of cancer families. The remaining two individuals carrying the CHK2 T59K mutation were diagnosed with breast cancer at the age of 42 years and colon cancer at the age of 66 years, respectively. The absence of complete segregation in one family with a history of colon cancer and a second family with breast cancer (in addition to other tumor types), and the low frequency of mutation in individuals with various tumor types, do not support the idea of a highly penetrant germ line variant, but the modifying effect on tumor pathogenesis may be of relevance.

We suggest that the T59K germ line variant is a low-penetrance allele with respect to tumor growth, but additional genetic variations of unknown origin may enhance the family history of cancer. Even though an amino acid is changed as a result of the sequence variation, this study does not clearly show, but does support, a dysfunctional variant. As suggested by the absence of sequence variants in the CHK2 gene in individuals carrying the BRCA2 999del5 mutation, there is no evidence of CHK2 acting as a modifying genetic factor on the tumor phenotype in these individuals. The remaining three germ line variants of CHK2 are also detected in the normal population and are therefore putative polymorphisms. The silent polymorphism at codon 84 has been reported earlier in other populations [14, 18], while the other two polymorphisms at a short mononucleotide stretch are novel.

The CHK2 gene is known to have several genomic copies through the genome that have a high sequence conservation [24]. Our sequence comparison indicates that the first 10 exons do not give problems due to DNA sequence homology between genes, but homology is detected for exon 11 to exon 14 of the CHK2 gene. In our primer set, only primers from exon 11 give a perfect match with an additional CHK2 copy from chromosome 10. Other primers for exons 12 to 14 have one to three nucleotide mismatches. It is therefore unlikely that the detected variants are from other copies of the CHK2 gene, since they are not from the highly conserved part of the gene. There is a risk that we are missing sequence variants from exons 11 to 14, although they could be detected as bands with weak intensity. It is therefore difficult to rely on this work being a full screen of CHK2 sequence variants.

In conclusion, CHK2 germ line mutations and somatic mutations are detected in breast cancer, but CHK2 inactivation does not play a major role in the cancer growth. Somatic mutations in the CHK2 gene are rare in breast tumors. The detected CHK2 T59K germ line allele is probably of low penetrance with respect to cancer growth. In breast cancer, mutations in TP53 and CHK2 genes probably explain only a part of the genetic instability detected in breast tumors.

Abbreviations

- LOH:

-

loss of heterozygosity

- PCR:

-

polymerase chain reaction

- RT:

-

reverse transcriptase

- SSCP:

-

single-strand conformation polymorphism.

References

Blasina A, deWeyer IV, Laus MC, Luyten WH, Parker AE, McGowan CH: A human homologue of the checkpoint kinase Cds1 directly inhibits Cdc25 phosphatase. Curr Biol. 1999, 9: 1-10. 10.1016/S0960-9822(99)80041-4.

Falck J, Mailand N, Syljuasen RG, Bartek J, Lukas J: The ATM-Chk2-Cdc25A checkpoint pathway guards against radioresistant DNA synthesis. Nature. 2001, 410: 842-847. 10.1038/35071124.

Furnari B, Blasina A, Boddy MN, McGowan CH, Russel P: Cdc25 inhibited in vivo and in vitro by checkpoint kinases Cds1 and Chk1. Mol Biol Cell. 1999, 10: 833-845.

Tominaga K, Morisaki H, Kaneko Y, Fujimoto A, Tanaka T, Ohtsubo M, Hirai M, Okayama H, Ikeda K, Nakanishi M: Role of human Cds1 (Chk2) kinase in DNA damage checkpoint and its regulation by p53. J Biol Chem. 1999, 274: 31463-31467. 10.1074/jbc.274.44.31463.

Chehab NH, Malikzay A, Appel M, Halazonetis TD: Chk2/hCds1 functions as a DNA damage checkpoint in G(1) by stabilizing p53. Genes Dev. 2000, 14: 278-288.

Lee JS, Collins KM, Brown AL, Lee CH, Chung JH: hCds1-mediated phosphorylation of BRCA1 regulates the DNA damage response. Nature. 2000, 404: 201-204. 10.1038/35004614.

Shieh SY, Ahn J, Tamai K, Taya Y, Prives C: The human homologs of checkpoint kinases Chk1 and Cds1 (Chk2) phosphorylate p53 at multiple DNA damage-inducible sites. Genes Dev. 2000, 14: 289-300.

Hirao A, Kong YY, Matsuoka S, Wakeham A, Ruland J, Yoshida H, Liu D, Elledge SJ, Mak TW: DNA damage-induced activation of p53 by the checkpoint kinase Chk2. Science. 2000, 287: 1824-1827. 10.1126/science.287.5459.1824.

Ahn JY, Schwarz JK, Piwnica-Worms H, Canman E: Threonine 68 phosphorylation by ataxia telangiectasia mutated is required for efficient activation of Chk2 in response to ionizing radiation. Cancer Res. 2000, 60: 5934-5936.

Chaturvedi P, Eng WK, Zhu Y, Mattern MR, Mishra R, Hurle MR, Zhang X, Annan RS, Lu Q, Faucette LF, Scott GF, Li X, Carr SA, Johnson RK, Winkler JD, Zhou BB: Mammalian Chk2 is a downstream effector of the ATM-dependent DNA damage checkpoint pathway. Oncogene. 1999, 18: 4047-4054. 10.1038/sj/onc/1202925.

Matsuoka S, Huang M, Elledge SJ: Linkage of ATM to cell cycle regulation by the Chk2 protein kinase. Science. 1988, 282: 1893-1897. 10.1126/science.282.5395.1893.

Matsuoka S, Rotman G, Ogawa A, Shiloh Y, Tamai K, Elledge SJ: Ataxia telangiectasia-mutated phosphorylates Chk2 in vivo and in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000, 97: 10389-10394. 10.1073/pnas.190030497.

Melchionna R, Chen XB, Blasina A, McGoan CH: Threonine 68 is required for radiation-induced phosphorylation and activation of Cds1. Nat Cell Biol. 2000, 2: 762-765. 10.1038/35036406.

Bell D, Varley JM, Szydlo TE, Kang DH, Wahrer DCR, Shannon KE, Lubratovich M, Verselis SJ, Isselbacher KJ, Fraumeni JF, Birch JM, Li FP, Garber JE, Haber DA: Heterozygous germ line hCHK2 mutations in Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Science. 1999, 286: 2528-2531. 10.1126/science.286.5449.2528.

Malkin D, Li FP, Strong LC, Fraumeni JF, Nelson CE, Kim DH, Kassel J, Gryka MA, Bischoff FZ, Tainsky MA, Friend SH: Germ line p53 mutations in a familial syndrome of breast cancer, sarcomas, and other neoplasms. Science. 1990, 250: 1233-1238.

Srivastava S, Zhou ZQ, Pirollo K, Blattner W, Chang EH: Germline transmission of a mutated p53 gene in a cancer-prone family with Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Nature. 1990, 348: 747-749. 10.1038/348747a0.

Wu X, Webster SR, Chen J: Characterization of tumor-associated Chk2 mutations. J Biol Chem. 2001, 276: 2971-2974. 10.1074/jbc.M009727200.

Haruki N, Saito H, Tatematsu Y, Konishi H, Harano R, Masuda A, Osada H, Fujii Y, Takahashi T: Histological type-selective, tumor-predominant expression of a novel CHK1 isoform and infrequent in vivo somatic CHK2 mutation in small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2000, 60: 4689-4692.

Hofmann WK, Miller CW, Tsukasaki K, Tavor S, Ikezoe T, Hoelzer D, Takeuchi S, Koeffler HP: Mutation analysis of the DNA-damage checkpoint gene CHK2 in myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemias. Leuk Res. 2001, 25: 333-338. 10.1016/S0145-2126(00)00130-2.

Tavor S, Takeuchi S, Tsukasaki K, Miller CW, Hofmann WK, Ikezoe T, Said JW, Koeffler HP: Analysis of the CHK2 gene in lymphoid malignancies. Leuk Lymph. 2001, 42: 517-520.

Johannesdottir G, Gudmundsson J, Bergthorsson JT, Arason A, Agnarsson BA, Eiriksdottir G, Johannsson OT, Borg A, Ingvarsson S, Easton DF, Egilsson V, Barkardottir RB: High prevalence of the 999del5 mutation in Icelandic breast and ovarian cancer patients. Cancer Res. 1996, 56: 3663-3665.

Huiping C, Sigurgeirsdottir JR, Jonasson JG, Eiriksdottir G, Johannsdottir JT, Egilsson V, Ingvarsson S: Chromosome alterations and E-cadherin gene mutations in human lobular breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1999, 81: 1103-1110. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690815.

Barkardottir RB, Arason A, Egilsson V, Gudmundsson J, Jonasdottir A, Johannesdottir G: Chromosome 17q-linkage seems to be infrequent in Icelandic families at risk of breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 1995, 34: 657-662.

Sodha N, Williams R, Mangion J, Bullock SL, Yuille MR, Eeles RA: Screening hCHK2 for mutations [letter]. Science. 2000, 289: 359-10.1016/S0378-4371(00)00333-2.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Icelandic Cancer Society and the University of Iceland Research Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ingvarsson, S., Sigbjornsdottir, B.I., Huiping, C. et al. Mutation analysis of the CHK2 gene in breast carcinoma and other cancers. Breast Cancer Res 4, R4 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr435

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr435