Abstract

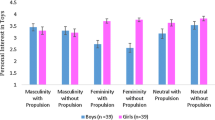

Tomboys are girls who behave like boys and, as such, challenge some theories of sex-typing. We recruited tomboys (N = 60) ages 4–9 through the media and compared them with their sisters (N = 15) and brothers (N = 20) on measures of playmate preference, sex-typed activities and interests, and gender identity. On nearly all measures, tomboys were substantially and significantly more masculine than their sisters, but they were generally less masculine than their brothers. We outline some scientific benefits of studying tomboys and describe some goals and initial findings of the Tomboy Project.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

Bailey, J. M., & Zucker, K. J. (1995). Childhood sex-typed behavior and sexual orientation: A conceptual analysis and quantitative review. Developmental Psychology, 31, 43-55.

Bechtold, K. T. (1996). Sex-segregation: Is it due to gender identity or toy and activity preferences? Unpublished master's thesis, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale.

Berenbaum, S. A. (1999). Effects of early androgens on sex-typed activities and interests in adolescents with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Hormones and Behavior, 35, 102-110.

Berenbaum, S. A., & Bailey, J. M. (1998). Variation in female gender identity: Evidence from girls with congenital adrenal hyperplasia, tomboys, and typical girls. Unpublished manuscript.

Berenbaum, S. A., Bryk, K., Levine, S., Huttenlocher, J., & Bailey, J. M. (1999, April). Associations between sex-typed play and spatial abilities in tomboys and typical girls. Poster presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Albuquerque, NM.

Berenbaum, S. A., & Hines, M. (1992). Early androgens are related to childhood sex-typed toy preferences. Psychological Science, 3, 203-206.

Berenbaum, S. A., & Resnick, S. M. (1997). Early androgen effects on aggression in children and adults with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 22, 505-515.

Berenbaum, S. A., & Snyder, E. (1995). Early hormonal influences on childhood sex-typed activity and playmate preferences: Implications for the development of sexual orientation. Developmental Psychology, 31, 31-42.

Bussey, K., & Bandura, A. (1999). Social cognitive theory of gender development and differentiation. Psychological Review, 106, 676-713.

Caspi, A., & Bem, D. J. (1990). Personality continuity and change across the life course. In L. A. Pervin (Ed.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 549-575). New York: Guilford.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Conley, J. J. (1984). Longitudinal consistency of adult personality: Selfreported psychological characteristics across 45 years. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 1325-1333.

Conley, J. J. (1985). Longitudinal stability of personality traits: A multitrait-multimethod-multioccasion analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49, 1266-1282.

Fridell, S. R., Zucker, K. J., Bradley, S. J., & Maing, D. M. (1996). Physical attractivenss of girls with gender identity disorder. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 25, 17-31.

Goy, R.W., Bercovitch, F. B., & McBrair, M. C. (1988). Behavioral maculinization is independent of genital masculinization in prenatally androgenized female rhesus macaques. Hormones and Behavior, 22, 552-571.

Green, R. (1987). The “sissy boy syndrome” and the development of homosexuality. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Green, R., Williams, K., & Goodman, M. (1982). Ninety-nine “tomboys” and “non-tomboys”: Behavioral contrasts and demographic similarities. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 11, 247-266.

Huston, A. C. (1983). Sex-typing. In E. M. Hetherington (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Socialization, personality, and social development (Vol. 4, pp. 388-467). New York: Wiley.

Hyde, J. S., Rosenberg, B. G., & Behrman, J. A. (1977). Tomboyism. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 2, 73-75.

Laumann, E. O., Gagnon, J. H., Michael, R. T., & Michaels, S. (1994). The social organization of sexuality: Sexual practices in the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Linn, M. C., & Peterson, A. C. (1985). Emergence and characterization of sex differences in spatial ability: A meta-analysis. Child Development, 56, 1479-1498.

Lippa, R. (1995). Do sex differences define gender-related individual differences within the sexes? Evidence from three studies. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21, 349-355.

Lippa, R., & Connelly, S. (1990). Gender diagnosticity: A new Bayesian approach to gender-related individual differences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 1051-1065.

Liss, M. B. (1981). Patterns of toy play: An analysis of sex differences. Sex Roles, 7, 1143-1150.

Maccoby, E. E. (1998). The two sexes: Growing up apart, coming together. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Martin, C. L. (1990). Attitudes and expectations about children with nontraditional and traditional gender roles. Sex Roles, 22, 151-165.

Martin, C. L. (1995). Stereotypes about children with traditional and nontraditional gender roles. Sex Roles, 33, 727-751.

Martin, C. L., & Halverson, C. F. (1981). A schematic processing model of sex typing and stereotyping in children. Child Development, 52, 1119-1134.

Merriam-Webster (Ed.). (1998). Merriam-Webster's collegiate dictionary (10th ed.). Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster.

Meyer-Bahlburg, H. F. L., Feldman, J. F., & Ehrhardt, A. A. (1985). Questionnaires for the assessment of atypical gender role behavior: Amethodological study. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 24, 695-701.

Morgan, B. L. (1998). A three generational study of tomboy behavior. Sex Roles, 39, 787-800.

Plumb, P., & Cowan, G. (1984). Adevelopmental study of destereotyping and androgynous activity preferences of tomboys, nontomboys, and males. Sex Roles, 10, 703-712.

Reinisch, J. M. (1981). Prenatal exposure to synthetic progestins increases potential for aggression in humans. Science, 211, 1171-1173.

Reinisch, J. M., & Sanders, S. A. (1986). A test of sex differences in aggressive response to hypothetical conflict situations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 1045-1049.

Ruble, D. N., & Martin, C. L. (1998). Gender development. In W. Damon (Series Ed.) & N. Eisenberg (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (5th ed., pp. 933-1016). New York: Wiley.

Sandberg, D. E., & Meyer-Bahlburg, H. F. L. (1994). Variability in middle childhood play behavior: Effects of gender, age, and family background. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 23, 645-663.

Serbin, L. A., Zelkowitz, P., Doyle, A., Gold, D., & Wheaton, B. (1990). The socialization of sex-differentiated skills and academic performance: A mediational model. Sex Roles, 23, 613-628.

Swanson, J. L. (1999). Stability and change in vocational interests. In M. Savickas & A. Spokane (Eds.), Vocational interests: Meaning, measurement and counseling use (pp. 135-158). Palo Alto, CA: Davies-Black.

Thorne, B. (1993). Gender play: Girls and boys in school. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Udry, J. R. (2000). Biological limites of gender construction. American Sociological Review, 65, 443-457.

Williams, K., Goodman, M., & Green, R. (1985). Parent-child factors in gender role socialization in girls. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 26, 720-731.

Williams, K., Green, R., & Goodman, M. (1979). Patterns of sexual identity development: A preliminary report on the “tomboy.” Research in Community and Mental Health, 1, 103-123.

Zucker, K. J., & Bradley, S. J. (1995). Gender identity disorder and psychosexual problems in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford.

Zucker, K. J., Bradley, S. J., Sullivan, C. L., Kuksis, M., Birkenfeld-Adams, A., & Mitchell, J. N. (1993). A gender identity interview for children. Journal of Personality Assessment, 61, 443-456.

Zuger, B. (1988). Is early effeminate behavior in boys early homosexuality? Comprehensive Psychiatry, 29, 509-519.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bailey, J.M., Bechtold, K.T. & Berenbaum, S.A. Who Are Tomboys and Why Should We Study Them?. Arch Sex Behav 31, 333–341 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016272209463

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016272209463