Abstract

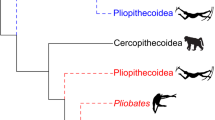

The eutherian orders Scandentia, Primates, Dermoptera, and Chiroptera have been grouped together by many morphologists, using various methods and data sets, into the cohort Archonta. Molecular evidence, however, has supported a clade (called Euarchonta) that includes Scandentia, Primates, and Dermoptera, but not Chiroptera. Within Archonta, some systematists have grouped Dermoptera and Chiroptera in Volitantia, while others have grouped Dermoptera and Primates in Primatomorpha. The order Scandentia includes the single family Tupaiidae, with two subfamilies, Ptilocercinae and Tupaiinae. Ptilocercinae is represented only by Ptilocercus lowii, which has been said to be the taxon most closely approximating the ancestral tupaiid. However, most researchers working on archontan phylogeny typically do not treat the order Scandentia as being polymorphic. They usually use Tupaia to represent Scandentia, despite the fact that Ptilocercus is quite distinct from Tupaia and has been argued to be the more plesiomorphic of the two taxa. In this study, a character analysis was performed on postcranial features that have been used to support the competing Primatomorpha and Volitantia hypotheses. In recognition of the polymorphic nature of Scandentia, taxonomic sampling within Scandentia was increased to include Ptilocercus. The postcranium of Ptilocercus was compared to that of tupaiines, euprimates, plesiadapiforms, dermopterans, and chiropterans. Several character states used to support either Primatomorpha or Volitantia, while not found in Tupaia, were found in Ptilocercus. While these features may have evolved independently in Ptilocercus, it is perhaps more likely that they represent features that first evolved in the ancestral archontan and were then lost in one of the extant orders. This character analysis greatly reduces the supportive evidence for the Primatomorpha hypothesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

LITERATURE CITED

Adkins, R. M., and Honeycutt, R. L. (1991). Molecular phylogeny of the superorder Archonta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88: 10317–10321.

Adkins, R. M., and Honeycutt, R. L. (1993). A molecular examination of archontan and chiropteran monophyly. In: Primates and their Relatives in Phylogenetic Perspective, R. D. E. MacPhee, ed., pp. 227–249, Plenum Press, New York.

Allard, M. W., McNiff, B. E., and Miyamoto, M. M. (1996). Support for interordinal eutherian relationships with an emphasis on primates and their archontan relatives. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 5: 78–88.

Bailey, W. J., Slightom, J. L., and Goodman, M. (1992). Rejection of the “flying primate” hypothesis by phylogenetic evidence from the E-globin gene. Science 256: 86–89.

Beard, K. C. (1989). Postcranial Anatomy, Locomotor Adaptations, and Paleoecology of Early Cenozoic Plesiadapidae, Paromomyidae, and Micromomyidae (Eutheria, Dermoptera). Ph.D. Dissertation, Johns Hopkins University.

Beard, K. C. (1990). Gliding behavior and paleoecology of the alleged primate family Paromomyidae (Mammalia, Dermoptera). Nature 345: 340–341.

Beard, K. C. (1991). Vertical postures and climbing in the morphotype of Primatomorpha: Implications for locomotor evolution in primate history. In: Origine(s) de la Bipédie chez les Hominidés, Y. Coppens and B. Senut, eds., pp. 79–87, CNRS, Paris.

Beard, K. C. (1993a). Origin and evolution of gliding in Early Cenozoic Dermoptera (Mammalia, Primatomorpha). In: Primates and their Relatives in Phylogenetic Perspective, R. D. E. MacPhee, ed., pp. 63–90, Plenum Press, New York.

Beard, K. C. (1993b). Phylogenetic systematics of the Primatomorpha, with special reference to Dermoptera. In: Mammal Phylogeny: Placentals, F. S. Szalay, M. J. Novacek, and M. C. McKenna, eds., pp. 129–150, Springer-Verlag, New York.

Bloch, J. I., and Silcox, M. T. (2001). New basicrania of Paleocene-Eocene Ignacius: Re-evaluation of the plesiadapiform-dermopteran link. Amer. J. Phys. Anthropol. 116: 184–198.

Boyer, D. M., Bloch, J. I., and Gingerich, P. D. (2001). New skeletons of Paleocene paromomyids (Mammalia, ?Primates): Were they mitten gliders? J. Vert. Paleontol. 21 (Supp. to No. 3): 5A.

Butler, P. M. (1972). The problem of insectivore classification. In: Studies in Vertebrate Evolution, K. A. Joysey and T. S. Kemp, eds., pp. 253–265, Oliver and Boyd, Edinburgh.

Butler, P. M. (1980). The tupaiid dentition. In: Comparative Biology and Evolutionary Relationships of Tree Shrews, W. P. Luckett, ed., pp. 171–204, Plenum, New York.

Campbell, C. B. G. (1966a). Taxonomic status of tree shrews. Science 153: 436.

Campbell, C. B. G. (1966b). The relationships of the tree shrews: The evidence of the nervous system. Evolution 20: 276–281.

Campbell, C. B. G. (1974). On the phyletic relationships of the tree shrews. Mammal. Rev. 4: 125–143.

Carleton, A. (1941). A comparative study of the inferior tibio-fibular joint. J. Anat. 76: 45–55.

Carlsson, A. (1922). Über die Tupaiidae und ihre Beziehungen zu den Insectivora und den Prosimiae. Acta Zool. 3: 227–270.

Cartmill, M., and MacPhee, R. D. E. (1980). Tupaiid affinities: The evidence of the carotid arteries and cranial skeleton. In: Comparative Biology and Evolutionary Relationships of Tree Shrews, W. P. Luckett, ed., pp. 95–132, Plenum, New York.

Chopra, S. R. K., and Vasishat, R. N. (1979). Sivalik fossil tree shrew from Haritalyangar, India. Nature 281: 214–215.

Chopra, S. R. K., Kaul, S., and Vasishat, R. N. (1979). Miocene tree shrews from the Indian Sivaliks. Nature 281: 213–214.

Cronin, J. E., and Sarich, V. M. (1980). Tupaiid and Archonta phylogeny: The macromolecular evidence. In: Comparative Biology and Evolutionary Relationships of Tree Shrews, W. P. Luckett, ed., pp. 293–312, Plenum, New York.

Dagosto, M. (1985). The distal tibia of primates with special reference to the Omomyidae. Int. J. Primatol. 6: 45–75.

Dagosto, M. (1988). Implications of postcranial evidence for the origin of euprimates. J. Hum. Evol. 17: 35–56.

Dutta, A. K. (1975). Micromammals from Siwaliks. Indian Minerals 29: 76–77.

Emmons, L. H. (2000). Tupai: A Field Study of Bornean Treeshrews, University of California Press, Berkeley.

Goodman, M., Bailey, W. J., Hayasaka, K., Stanhope, M. J., Slightom, J., and Czelusniak, J. (1994). Molecular evidence on primate phylogeny from DNA sequences. Amer. J. Phys. Anthropol. 94: 3–24.

Gould, E. (1978). The behavior of the moonrat, Echinosorex gymnurus (Erinaceidae) and the pentail tree shrew, Ptilocercus lowii (Tupaiidae) with comments on the behavior of other Insectivora. Z. Tierpsychol. 48: 1–27.

Graur, D., Duret, L., and Gouy, M. (1996). Phylogenetic position of the order Lagomorpha (rabbits, hares and allies). Nature 379: 333–335.

Gregory, W. K. (1910). The orders of mammals. Bull. Amer. Mus. Nat. Hist. 27: 1–524.

Haeckel, E. (1866). Generelle Morphologie Der Organismen, Georg Reimer, Berlin.

Hamrick, M. W., Rosenman, B. A., and Brush, J. A. (1999). Phalangeal morphology of the Paromomyidae (?Primates, Plesiadapiformes): The evidence for gliding behavior reconsidered. Amer. J. Phys. Anthropol. 109: 397–413.

Honeycutt, R. L., and Adkins, R. M. (1993). Higher level systematics of eutherian mammals: An assessment of molecular characters and phylogenetic hypotheses. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 24: 279–305.

Jacobs, L. L. (1980). Siwalik fossil tree shrews. In: Comparative Biology and Evolutionary Relationships of Tree Shrews, W. P. Luckett, ed., pp. 205–216, Plenum, New York.

Jane, J. A., Campbell, C. B. G., and Yashon, D. (1965). Pyramidal tract: A comparison of two prosimian primates. Science 147: 153–155.

Johnson, J. I., and Kirsch, J. A. W. (1993). Phylogeny through brain traits: Interordinal relationships among mammals including Primates and Chiroptera. In: Primates and their Relatives in Phylogenetic Perspective, R. D. E. MacPhee, ed., pp. 293–331, Plenum Press, New York.

Kay, R. F., Thorington, R. W., and Houde, P. (1990). Eocene plesiadapiform shows affinities with flying lemurs not primates. Nature 345: 342–344.

Kay, R. F., Thewissen, J. G. M., and Yoder, A. D. (1992). Cranial anatomy of Ignacius graybullianus and the affinities of the Plesiadapiformes. Amer. J. Phys. Anthropol. 89: 477–498.

Killian, J. K., Buckley, T. R., Stewart, N., Munday, B. L., and Jirtle, R. L. (2001). Marsupials and eutherians reunited: Genetic evidence for the Theria hypothesis of mammalian evolution. Mammal. Gen. 12: 513–517.

Krause, D. W. (1991). Were paromomyids gliders? Maybe, maybe not. J. Hum. Evol. 21: 177–188.

Kriz, M., and Hamrick, M. W. (2001). The postcranial evidence for primate superordinal relationships. Amer. J. Phys. Anthropol. Supp. 32: 93.

Le Gros Clark, W. E. (1924a). The myology of the tree shrew (Tupaia minor). Proc. Zool. Soc. Lond. 1924: 461–497.

Le Gros Clark, W. E. (1924b). On the brain of the tree shrew (Tupaia minor). Proc. Zool. Soc. Lond. 1924: 1053–1074.

Le Gros Clark, W. E. (1925). On the skull of Tupaia. Proc. Zool. Soc. Lond. 1925: 559–567.

Le Gros Clark, W. E. (1926). On the anatomy of the pen-tailed tree shrew (Ptilocercus lowii). Proc. Zool. Soc. Lond. 1926: 1179–1309.

Lemelin, P. (2000). Micro-anatomy of the volar skin and interordinal relationships of primates. J. Hum. Evol. 38: 257–267.

Liu, F.-G. R., and Miyamoto, M. M. (1999). Phylogenetic assessment of molecular and morphological data for eutherian mammals. Syst. Biol. 48: 54–64.

Liu, F.-G. R., Miyamoto, M. M., Freire, N. P., Ong, P. Q., Tennant, M. R., Young, T. S., and Gugel, K. F. (2001). Molecular and morphological supertrees for eutherian (placental) mammals. Science 291: 1786–1789.

Luckett, W. P. (ed.) (1980). Comparative Biology and Evolutionary Relationships of Tree Shrews, Plenum Press, New York.

Luckett, W. P. (1993). Developmental evidence from the fetal membranes for assessing archontan relationships. In: Primates and their Relatives in Phylogenetic Perspective, R. D. E. MacPhee, ed., pp. 149–186, Plenum Press, New York.

MacPhee, R. D. E. (1981). Auditory Regions of Primates and Eutherian Insectivores: Morphology, Ontogeny, and Character Analysis. Contrib. Primatol. 18: 1–282.

MacPhee, R. D. E. (ed.) (1993). Primates and Their Relatives in Phylogenetic Perspective, Plenum Press, New York.

Madsen, O., Scally, M., Douady, C. J., Kao, D. J., DeBry, R. W., Adkins, R. M., Amrine, H. M., Stanhope, M. J., de Jong, W. W., and Springer, M. S. (2001). Parallel adaptive radiations in two major clades of placental mammals. Nature 409: 610–614.

Martin, R. D. (1966). Tree shrews: Unique reproductive mechanism of systematic importance. Science 152: 1402–1404.

Martin, R. D. (1968a). Towards a new definition of primates. Man 3: 377–401.

Martin, R. D. (1968b). Reproduction and ontogeny in tree shrews (Tupaia belangeri), with reference to their general behavior and taxonomic relationships. Z. Tierpsychol. 25: 409–532.

Martin, R. D. (1990). Primate Origins and Evolution, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

McKenna, M. C. (1966). Paleontology and the origin of the primates. Folia Primatol. 4: 1–25.

McKenna, M. C. (1975). Toward a phylogenetic classification of the Mammalia. In: Phylogeny of the Primates: A Multidisciplinary Approach, W. P. Luckett and F. S. Szalay, eds., pp. 21–46, Plenum Press, New York.

McKenna, M. C., and Bell, S. K. (1997). Classification of Mammals Above the Species Level, Columbia University Press, New York.

Mein, P., and Ginsburg, L. (1997). Les mammiféres du gisement miocéne inférieur de Li Mae Long, Thailande: Systématique, biostratigraphie et paléoenvironnement. Geodiversitas 19: 783–844.

Miyamoto, M. M. (1996). A congruence study of molecular and morphological data for eutherian mammals. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 6: 373–390.

Murphy, W. J., Eizirik, E., Johnson, W. E., Zhang, Y. P., Ryder, O. A., and O'Brien, S. J. (2001a). Molecular phylogenetics and the origins of placental mammals. Nature 409: 614–618.

Murphy, W. J., Eizirik, E., O'Brien, S. J., Madsen, O., Scally, M., Douady, C. J., Teeling, E. C., Ryder, O. A., Stanhope, M. J., de Jong, W. W., and Springer, M. S. (2001b). Resolution of the early placental mammal radiation using Bayesian phylogenetics. Science 294: 2348–2351.

Napier, J. R., and Napier, P. H. (1967). A Handbook of Living Primates, Academic, London.

Novacek, M. J. (1980). Cranioskeletal features in tupaiids and selected Eutheria as phylogenetic evidence. In: Comparative Biology and Evolutionary Relationships of Tree Shrews, W. P. Luckett, ed., pp. 35–93, Plenum, New York.

Novacek, M. J. (1982). Information for molecular studies from anatomical and fossil evidence on higher eutherian phylogeny. In: Macromolecular Sequences in Systematic and Evolutionary Biology, M. Goodman, ed., pp. 3–41, Plenum Press, New York.

Novacek, M. J. (1986). The skull of leptictid insectivorans and the higher-level classification of eutherian mammals. Bull. Amer. Mus. Nat. Hist. 183: 1–112.

Novacek, M. J. (1989). Higher mammal phylogeny: The morphological-molecular synthesis. In: The Hierarchy of Life, B. Fernholm, K. Bremer, and H. Jornvall, eds., pp. 421–435, Elsevier, Amsterdam.

Novacek, M. J. (1990). Morphology, paleontology, and the higher clades of mammals. In: Current Mammalogy, H. H. Genoways, ed., pp. 507–543, Plenum Press, New York.

Novacek, M. J. (1992). Mammalian phylogeny: Shaking the tree. Nature 356: 121–125.

Novacek, M. J. (1993). Reflections on higher mammalian phylogenetics. J. Mammal. Evol. 1: 3–30.

Novacek, M. J. (1994). Morphological and molecular inroads to phylogeny. In: Interpreting the Hierarchy of Nature, L. Grande and O. Rieppel, eds., pp. 85–131, Academic Press, New York.

Novacek, M. J., and Wyss, A. R. (1986). Higher-level relationships of the recent eutherian orders: Morphological evidence. Cladistics 2: 257–287.

Novacek, M. J., Wyss, A. R., and McKenna, M. C. (1988). The major groups of eutherian mammals. In: The Phylogeny and Classification of the Tetrapods, Vol. 2: Mammals, M. J. Benton, ed., pp. 31–71, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Porter, C. A., Goodman, M., and Stanhope, M. J. (1996). Evidence on mammalian phylogeny from sequences of exon 28 of the von Willebrand factor gene. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 5: 89–101.

Qiu, Z. (1986). Fossil tupaiid from the hominoid locality of Lufeng, Yunnan. Vert. PalAsiatica 24: 308–319.

Rose, K. D. (1999). Postcranial skeleton of Eocene Leptictidae (Mammalia), and its implications for behavior and relationships. J. Vert. Paleontol. 19: 355–372.

Rose, K. D., and Lucas, S. G. (2000). An early Paleocene palaeanodont (Mammalia, ?Pholidota) from New Mexico, and the origin of Palaeanodonta. J. Vert. Paleontol. 20: 139–156.

Runestad, J. A., and Ruff, C. B. (1995). Structural adaptations for gliding in mammals with implications for locomotor behavior in paromomyids. Amer. J. Phys. Anthropol. 98: 101–119.

Sargis, E. J. (1999). Tree shrews. In: Encyclopedia of Paleontology, R. Singer, ed., pp. 1286–1287, Fitzroy Dearborn, Chicago.

Sargis, E. J. (2000). The Functional Morphology of the Postcranium of Ptilocercus and Tupaiines (Scandentia, Tupaiidae): Implications for the Relationships of Primates and other Archontan Mammals. Ph.D. Dissertation, City University of New York.

Sargis, E. J. (2001a). A preliminary qualitative analysis of the axial skeleton of tupaiids (Mammalia, Scandentia): Functional morphology and phylogenetic implications. J. Zool. Lond. 253: 473–483.

Sargis, E. J. (2001b). The phylogenetic relationships of archontan mammals: Postcranial evidence. J. Vert. Paleontol. 21 (Supp. to No. 3): 97A.

Sargis, E. J. (2001c). The grasping behaviour, locomotion and substrate use of the tree shrews Tupaia minor and T. tana (Mammalia, Scandentia). J. Zool. Lond. 253: 485–490.

Sargis, E. J. (2002a). Functional morphology of the forelimb of tupaiids (Mammalia, Scandentia) and its phylogenetic implications. J. Morph. 253: 10–42.

Sargis, E. J. (2002b). Functional morphology of the hindlimb of tupaiids (Mammalia, Scandentia) and its phylogenetic implications. J. Morph. 254: 149–185.

Sargis, E. J. (in press) A multivariate analysis of the postcranium of tree shrews (Scandentia, Tupaiidae) and its taxonomic implications. Mammalia.

Schlosser-Sturm, E., and Schliemann, H. (1995). Morphology and function of the shoulder joint of bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera). Z. zool. Syst. Evolut.-forsch. 33: 88–98.

Schmitz, J., Ohme, M., and Zischler, H. (2000). The complete mitochondrial genome of Tupaia belangeri and the phylogenetic affiliation of Scandentia to other eutherian orders. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17: 1334–1343.

Shoshani, J., Groves, C. P., Simons, E. L., and Gunnell, G. F. (1996). Primate phylogeny: Morphological vs molecular results. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 5: 102–154.

Shoshani, J., and McKenna, M. C. (1998). Higher taxonomic relationships among extant mammals based on morphology, with selected comparisons of results from molecular data. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 9: 572–584.

Silcox, M. T. (2001a). A phylogenetic analysis of Plesiadapiformes and their relationship to euprimates and other archontans. J. Vert. Paleontol. 21 (Supp. to No. 3): 101A.

Silcox, M. T. (2001b). A Phylogenetic Analysis of Plesiadapiformes and Their Relationship to Euprimates and Other Archontans. Ph.D. Dissertation, Johns Hopkins University.

Silcox, M. T. (2002). The phylogeny and taxonomy of plesiadapiforms. Amer. J. Phys. Anthropol. Supp. 34: 141–142.

Simmons, N. B. (1994). The case for chiropteran monophyly. Amer. Mus. Nov. 3103: 1–54.

Simmons, N. B. (1995). Bat relationships and the origin of flight. Symp. Zool. Soc. Lond. 67: 27–43.

Simmons, N. B., and Quinn, T. H. (1994). Evolution of the digital tendon locking mechanism in bats and dermopterans: A phylogenetic perspective. J. Mammal. Evol. 2: 231–254.

Simpson, G. G. (1945). The principles of classification and a classification of mammals. Bull. Amer. Mus. Nat. Hist. 85: 1–350.

Smith, J. D., and Madkour, G. (1980). Penial morphology and the question of chiropteran phylogeny. In: Proceedings of the Fifth International Bat Research Conference, D. E. Wilson and A. L. Gardner, eds., pp. 347–365, Texas Tech Press, Lubbock, Texas.

Stafford, B. J., and Thorington, R. W. (1998). Carpal development and morphology in archontan mammals. J. Morph. 235: 135–155.

Stanhope, M. J., Bailey, W. J., Czelusniak, J., Goodman, M., Si, J.-S., Nickerson, J., Sgouros, J. G., Singer, G. A. M., and Kleinschmidt, T. K. (1993). A molecular view of primate supraordinal relationships from the analysis of both nucleotide and amino acid sequences. In: Primates and their Relatives in Phylogenetic Perspective, R. D. E. MacPhee, ed., pp. 251–292, Plenum Press, New York.

Stanhope, M. J., Smith, M. R., Waddell, V. G., Porter, C. A., Shivji, M. S., and Goodman, M. (1996). Mammalian evolution and the interphotoreceptor retinoid binding protein (IRBP) gene: Convincing evidence for several superordinal clades. J. Mol. Evol. 43: 83–92.

Steele, D. G. (1973). Dental variability in the tree shrews (Tupaiidae). In: Craniofacial Biology of Primates: Symposium of the IVth International Congress of Primatology, Vol. 3, M. R. Zingeser, ed., pp. 154–179, Karger, Basel.

Szalay, F. S. (1968). The beginnings of primates. Evolution 22: 19–36.

Szalay, F. S. (1969). Mixodectidae, Microsyopidae, and the insectivore-primate transition. Bull. Amer. Mus. Nat. Hist. 140: 193–330.

Szalay, F. S. (1977). Phylogenetic relationships and a classification of the eutherian Mammalia. In: Major Patterns in Vertebrate Evolution, M. K. Hecht, P. C. Goody, and B. M. Hecht, eds., pp. 315–374, Plenum Press, New York.

Szalay, F. S. (1999). Review of “Classification of Mammals above the Species Level” by M.C. McKenna and S.K. Bell. J. Vert. Paleontol. 19: 191–195.

Szalay, F. S., and Dagosto, M. (1980). Locomotor adaptations as reflected on the humerus of Paleogene primates. Folia Primatol. 34: 1–45.

Szalay, F. S., and Dagosto, M. (1988). Evolution of hallucial grasping in the primates. J. Hum. Evol. 17: 1–33.

Szalay, F. S., and Drawhorn, G. (1980). Evolution and diversification of the Archonta in an arboreal milieu. In: Comparative Biology and Evolutionary Relationships of Tree Shrews, W. P. Luckett, ed., pp. 133–169, Plenum, New York.

Szalay, F. S., and Lucas, S. G. (1993). Cranioskeletal morphology of archontans, and diagnoses of Chiroptera, Volitantia, and Archonta. In: Primates and their Relatives in Phylogenetic Perspective, R. D. E. MacPhee, ed., pp. 187–226, Plenum Press, New York.

Szalay, F. S., and Lucas, S. G. (1996). The postcranial morphology of Paleocene Chriacus and Mixodectes and the phylogenetic relationships of archontan mammals. Bull. New Mex. Mus. Nat. Hist. Sci. 7: 1–47.

Szalay, F. S., Rosenberger, A. L., and Dagosto, M. (1987). Diagnosis and differentiation of the order Primates. Yrbk. Phys. Anthropol. 30: 75–105.

Teeling, E. C., Scally, M., Kao, D. J., Romagnoli, M. L., Springer, M. S., and Stanhope, M. J. (2000). Molecular evidence regarding the origin of echolocation and flight in bats. Nature 403: 188–192.

Thewissen, J. G. M., and Babcock, S. K. (1991). Distinctive cranial and cervical innervation of wing muscles: New evidence for bat monophyly. Science 251: 934–936.

Thewissen, J. G. M., and Babcock, S. K. (1992). The origin of flight in bats. Bioscience 42: 340–345.

Thewissen, J. G. M., and Babcock, S. K. (1993). The implications of the propatagial muscles of flying and gliding mammals for archontan systematics. In: Primates and their Relatives in Phylogenetic Perspective, R. D. E. MacPhee, ed., pp. 91–109, Plenum Press, New York.

Tong, Y. (1988). Fossil tree shrews from the Eocene Hetaoyuan Formation of Xichuan, Henan. Vert. PalAsiatica 26: 214–220.

Van Valen, L. M. (1965). Tree shrews, primates, and fossils. Evolution 19: 137–151.

Waddell, P. J., Okada, N., and Hasegawa, M. (1999). Towards resolving the interordinal relationships of placental mammals. Syst. Biol. 48: 1–5.

Wagner, J. A. (1855). Die Säugethiere in Abbildungen Nach Der Natur, Weiger, Leipzig.

Wible, J. R. (1993). Cranial circulation and relationships of the colugo Cynocephalus (Dermoptera, Mammalia). Amer. Mus. Nov. 3072: 1–27.

Wible, J. R., and Covert, H. H. (1987). Primates: Cladistic diagnosis and relationships. J. Hum. Evol. 16: 1–22.

Wible, J. R., and Martin, J. R. (1993). Ontogeny of the tympanic floor and roof in archontans. In: Primates and their Relatives in Phylogenetic Perspective, R. D. E. MacPhee, ed., pp. 111–148, Plenum Press, New York.

Wible, J. R., and Novacek, M. J. (1988). Cranial evidence for the monophyletic origin of bats. Amer. Mus. Nov. 2911: 1–19.

Wible, J. R., and Zeller, U. A. (1994). Cranial circulation of the pen-tailed tree shrew Ptilocercus lowii and relationships of Scandentia. J. Mammal. Evol. 2: 209–230.

Wilson, D. E. (1993). Order Scandentia. In: Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, D. E. Wilson and D. M. Reeder, eds., pp. 131–133, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

Wöhrmann-Repenning, A. (1979). Primate characters in the skull of Tupaia glis and Urogale everetti (Mammalia, Tupaiiformes). Senckenberg. Biol. 60: 1–6.

Zeller, U. A. (1986a). Ontogeny and cranial morphology of the tympanic region of the Tupaiidae, with special reference to Ptilocercus. Folia Primatol. 47: 61–80.

Zeller, U. A. (1986b). The systematic relations of tree shrews: Evidence from skull morphogenesis. In: Primate Evolution, J. G. Else and P. C. Lee, eds., pp. 273–280, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Zeller, U. A. (1987). Morphogenesis of the mammalian skull with special reference to Tupaia. In: Morphogenesis of the Mammalian Skull, H. J. Kuhn and U. A. Zeller, eds., pp. 17–50, Verlag Paul Parey, Hamburg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sargis, E.J. The Postcranial Morphology of Ptilocercus lowii (Scandentia, Tupaiidae): An Analysis of Primatomorphan and Volitantian Characters. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 9, 137–160 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021387928854

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021387928854