Abstract

In recent years Colombia has grown relatively rapidly, but it has been a biased growth. The energy sector (the locomotora minero-energetica, to use the rhetorical expression of President Juan Manuel Santos) grew much faster than the rest of the economy, while the manufacturing sector registered a negative rate of growth. These are classic symptoms of the well-known ‘Dutch disease’, but our purpose here is not to establish whether the Dutch disease exists or not, but rather to shed some light on the financial viability of several, simultaneous dynamics: (1) the existence of a traditional Dutch Disease being due to a large increase in mining exports and a significant exchange rate appreciation, (2) a massive increase in foreign direct investment (FDI), particularly in the mining sector, (3) a rather passive monetary policy, aimed at increasing purchasing power via exchange rate appreciation, (4) more recently, a large distribution of dividends from Colombia to the rest of the world and the accumulation of mounting financial liabilities. The paper will show that these dynamics constitute a potential danger for the stability of the Colombian economy. Some policy recommendations are also discussed.

Source: DANE

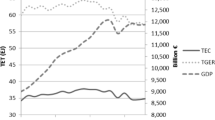

Source: Central Bank of Colombia

Source: UNCTAD Datastat

Source: Central Bank of Colombia and Authors’ computations

Source: from Central Bank of Colombia and Author’s computation

Source: DANE

Source: Ministero of Finance and Public Credit (2014b), Central Bank of Colombia and Authors’ computation

Source: Ministero of Finance and Public Credit (2014b), Central Bank of Colombia and Authors’ computation

Source: from Ministero of Finance and Public Credit (2014b), Central Bank of Colombia and Authors’ computation

Source: from Ministero of Finance and Public Credit (2014b), Central Bank of Colombia and Authors’ computation

Source: from Ministero of Finance and Public Credit (2014b), Central Bank of Colombia and Authors’ computation

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

CIVETS stands for Colombia, Indonesia, Vietnam, Egypt, Turkey and South Africa.

In the last decade, Colombian per capita income grew at rates that are certainly not comparable to the fastest-growing Asian economies. Still, despite an inevitable slowdown from 2007 to 2009, Colombian per capita GNI grew annually at an average of 5.3 % between 2004 and 2013.

Following Coelho and Gallagher (2013), Colombia temporary introduced some capital controls in order to tame booming capital inflows and reduce pressures on real exchange rate appreciation from May 2007 to October 2008. These measures, however, have proved to be too mild to reach their targets and thus have been lifted since then.

See Ministry of Finance and Public Credit (2014a), ‘An Outlook of the Colombian Economy’, freely available for download at http://www.minhacienda.gov.co/HomeMinhacienda/saladeprensa/Presentaciones.

Increasing exploitation of domestic natural resources and high commodity prices are usually associated to long-lasting current account surpluses, see Ojeda et al. (2014) for example.

Goda and Torres (2013) perform an econometric analysis in order to test the existence of any effects of FDI on Colombian real exchange rate and, in turn, on manufacturing development. Their sample coverage runs from 1996 (first quarter) to 2012 (first quarter). On the one hand, they conclude that ‘net FDI and net other inflows are the main drivers of the post-2003 capital inflow appreciation effect in Colombia (Goda and Torres 2013, p. 16)’. On the other hand, they find that real exchange rate appreciation explains most of the de-industrialization episode currently underway in Colombia.

Corden and Neary (1982) assume a Hicks-neutral technological progress to take place in the energy sector, raising both labor and capital productivity in that sector. Similar results could also be obtained if an increase of primary commodities’ prices is assumed and the country under consideration is a net exporter of primary energy commodities, or if there is an increase in the endowment of the natural resource input specific to the energy sector.

Torvik (2001) allows for different results by allowing for learning-by-doing to take place in the non-tradable sector as well, and technological spill-over running both ways (from manufacturing to services and vice versa).

Different conclusions with respect to the standard ‘Dutch disease’ literature can be obtained when inter-temporal optimization and consumption smoothing is allowed through financial market mechanisms. Mansoorian (1991), for instance, finds that a real depreciation and an expanding manufacturing sector could emerge in the long run as the optimal response to over-borrowing, real exchange rate appreciation and de-industrialization in the short run. These conclusions reinforce those provided by Bruno and Sachs, who stress that ‘optimizing far-sight households (and government) will not consume all current oil revenues, but will rather save in anticipation of the future decline […] to the extent that the current revenues overstate the ‘perpetuity equivalent’ of oil earnings, a focus on current production levels overstates the resource allocation consequences of the oil sector (Bruno and Sachs 1982, p. 858)’.

Considering the interplay between financial and real factors in the analysis of Dutch disease is not completely new. See, for instance, Blecker and Seccareccia (2008).

The debate on Colombian deindustrialization dates back to at least 1986, see Kamas (1986).

Tregenna (2011) identifies three possible processes leading to de-industrialization as measured by a reduction of the manufacturing employment share. First, a reduction in labor-intensity (increase in labor productivity) coupled with a contraction of that sector output; second, a reduction in labor-intensity that outweighs the expansion of sector production; finally, the contraction of sectorial activity that outweighs the increase in labor-intensity (decline in labor productivity). Such processes, all giving rise to a lower manufacturing employment share, are likely to prompt different and perhaps opposite effects on overall economic records. This is also the reason why analogous trends in manufacturing employment in Asian and Latin American economies, Colombia among them, have been often associated to diverging economic performances. Whilst the former registered increasing manufacturing value added shares and even stronger improvements in manufacturing labor productivity, most Latin American economies experienced worrisome premature reductions in manufacturing GDP shares, and dismal increases in labor productivity by international standards. Indeed, ‘if a decrease in manufacturing employment share is primarily accounted for by falling labor-intensity of manufacturing, this calls into question the extent to which ‘de-industrialization’ is an appropriate characterization. The point is that a fall in the share of manufacturing employment that is mostly accounted for by falling labor intensity (i.e. increasing labor productivity) would not necessary have a negative impact on growth. This is different from the case where the fall in the share of manufacturing employment is associated primarily with a decline of the manufacturing sector as a share of GDP. In such a scenario, an economy would be particularly at risk of losing out on the growth-pulling effects of manufacturing (Tregenna 2011 p. 15).’

Variations in the sectorial employment share can be decomposed into three elements: variations in the labor-intensity characterizing sector’s production (i.e. the labor-intensity effect); variations in the sectorial GDP share (i.e. the sector share effect); variations of overall labor productivity, which obviously affect overall employment dynamics (i.e. the above labor-productivity effects). We can represent the sectorial employment share (hence its variation) according to this formula: \(\frac{{L_{it} }}{{L_{t} }} = \frac{{L_{it} }}{{Y_{it} }} \times \frac{{Y_{it} }}{{Y_{t} }} \times \frac{{Y_{t} }}{{L_{t} }}\), L it being employment level in sector i at time t, Y it sectorial production at time t, L t and Y t overall employment and production levels. It is worth noting that the sectorial labor intensity (or the inverse of the labor productivity) is a output-weighted average of each sub-sector labor intensities. Thus, a decrease in labor productivity does not necessarily imply using a less efficient technology but can be the result of a change of the output shares in favor of a more labor-intensive sub-sector.

See UNCTAD (2014), ‘Manufactured goods by degree of manufacturing’, freely available for download from http://unctadstat.unctad.org/EN/Classifications.html.

United States of America (22/11/2006), Chile (27/11/2006), Northern Triangle (El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, 09/08/2007), Canada (21/11/2008), European Free Trade Association (25/11/2011) and European Union (26/06/2012), source: Organization of American State’s Foreign Trade Information System, http://www.sice.oas.org.

In Fig. 3, according to UNCTAD data, upward trends in the nominal and real effective exchange rate indexes stand for appreciations. Depreciations are represented by downward sloping sections in exchange rates dynamics.

According to data provided by the IMF (2014), from 2003 to 2012, Colombia has experienced average inflation rates significantly lower than those observed in other emerging economies such as Brazil (1.6 % point less), India (2.6), South Africa (0.8) and Turkey (5.7).

See IMF World Economic Outlook (April 2014). Data freely available from http://www.imf.org.

The R source code and the datasets used to generate all graphs and econometric results of this paper can be found on the website of one of the authors.

Unfortunately, we do not have detailed yearly values for the financial account and Foreign Direct Investment but only averages over the time period.

It must be emphasized that, due to the mining-sector boom, the evolution of non-primary exports over the last decade has been particularly disappointing. The share of primary export (oil, coffee, flowers, bananas, etc.) in total exports rose from 74 % in 2001 to 81 % in 2012 (Consejo Privado de Competitividad 2013).

See Ocampo (2009) on the disruptive effects on the Colombian external account of a possible reduction in the price of primary commodities.

References

Blecker, R.A., & Seccareccia, M. (2008). Would a North American monetary union protect Canada and Mexico against the ravages of “Dutch disease”? A post-financial crisis perspective—Paper prepared for “The Political Economy of Monetary Policy and Financial Regulation: A Conference in Honor of Jane D’Arista,” May 2–3, 2008, Political Economy Research Institute (PERI), University of Massachusetts, Amherst, USA.

Botta, A. (2010). Economic development, structural change and natural resource booms: a structuralist perspective. Metroeconomica, 61(3), 510–539.

Bruno, M., & Sachs, J. D. (1982). Energy and resource allocation: a dynamic model of the “Dutch Disease”. Review of Economic Studies, 49(5), 845–859.

Cabrera Galvis, M. C. (2013). Diez Años de Revaluación. Bogotà: Editorial Oveja Negra.

Chang, H. J. (2010). 23 Things they don’t tell you about capitalism. London: Penguin Books.

Coelho, B., & Gallagher, K. P. (2013). The effectiveness of capital controls: evidence from Colombia and Thailand. International Review of Applied Economics, 27(3), 386–403.

Consejo Privado de Competitividad. (2013). Informe Nacional de Competitividad 2013–2014. Bogotá.

Corden, W. M., & Neary, J. P. (1982). Booming sector and de-industrialization in a small open economy. The Economic Journal, 92(368), 825–848.

DANE. (2014). DANE supply and uses matrix table. Freely available for download from https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/cuentas-economicas/cuentas-anuales.

Dutt, A. K. (1997). The pattern of direct foreign investment and economic growth. World Development, 25(11), 1925–1936.

The Economist Intelligence Unit. (2013). Latin America as an FDI Hotspot: opportunities and risks.

Goda, T., & Torres, A. (2013). Overvaluation of the real exchange rate and the dutch disease: the Colombian case. CIEF Working Paper n. 28–13.

Gylfason, T., Herbertsson, T. T., & Zoega, G. (1999). A mixed blessing: natural resources and economic growth. Macroeconomic Dynamics, 3(2), 204–225.

Hausmman, R., Hwang, J., & Rodrik, D. (2007). What you export matters. Journal of Economic Growth, 12(1), 1–25.

Hernandez Jimenez, G., & Razmi, A. (2014). Latin America after the global crisis: the role of export-led and tradable-led growth regimes. International Review of Applied Economics, 28(6), 713–741.

Imbs, J., & Wacziarg, R. (2003). Stages of diversification. American Economic Review, 93(1), 63–86.

IMF. (2014). World economic outlook April 2014.

IMF. (2015). IMF Country Report on Colombia n. 15/142.

Kamas, L. (1986). Dutch disease economics and the colombian export boom. World Development, 14(9), 1177–1198.

Mansoorian, A. (1991). Resource discoveries and excessive external borrowing. The Economic Journal, 101(409), 1497–1509.

Manzano, O., & Rigobon, R. (2001). Resource curse or debt overhang, NBER Working Paper n. 8390.

Ministero of Finance and Public Credit. (2014b). Marco Fiscal de Mediano Plazo, June 2014.

Ministry of Finance and Public Credit. (2014a). An outlook of the Colombian economy, freely available for download at http://www.minhacienda.gov.co.

Missaglia, M. (2012). Finanza, Povertà e Tensioni Internazionali. In F. Strazzari (Ed.), Mercati di Guerra. Bologna: il Mulino.

Missaglia, M. (2014). Impacto de los TLC en los departamentos colombianos. Consideraciones de Política Económica, Final Report, CID (Centro de Investigaciones para el Desarrollo), Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Ocampo, J. A. (1994). Trade policy and industrialization in Colombia, 1967–91. In G. K. Helleiner (Ed.), Trade policy and industrialization in turbulent times (pp. 132–169). Routhledge: New York.

Ocampo, J. A. (2009). Performance and challenges of the Colombian economy. Freely available for download from http://policydialogue.org/publications.

Ocampo, J. A. (2013). Prologo. In M. C. Cabrera Galvis (Ed.), Diez Años de Revaluación. Bogotà: Editorial Oveja Negra.

OECD. (2013). OECD economic assessment of Colombia 2013. Available from http://www.oecd.org/Colombia.

Ojeda, J.N., Parra-Polonia, A., & Vargas, C.O. (2014). Natural-resource booms, fiscal rules and welfare in a small open economy. Banco de la Republica Colombiana Borradores de Economia n. 807.

Park Madison Partners. (2013). Colombia’s rise: a primer for international investors. Freely available for download from http://www.parkmadisonpartners.com/cgi-bin/news.pl.

Rodrik, D. (2007). Industrial development: some stylised facts and policy directions. In UN-DESA (Ed.), Industrial development for the 21st century: sustainable development perspectives. New York: UN Publishing.

Ros, J. (2001). Industrial policy, comparative advantages and growth. CEPAL Review, 73, 127–145.

Sachs, J.D., & Warner, A.M. (1995). Natural resource abundance and economic growth. NBER Working Paper n. 5398.

Sachs, J. D., & Warner, A. M. (1999). The big push, natural resource booms and growth. Journal of Development Economics, 59(1), 43–76.

Sachs, J. D., & Warner, A. M. (2001). The curse of natural resources. European Economic Review, 45(4), 827–838.

Singh, A. (2003). Capital account liberalization, free long-term capital flows, financial crises and economic development. Eastern Economic Journal, 29(2), 191–216.

Szirmai, (2012). Industrialization as an engine of growth in developing countries, 1950–2005. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 23(4), 406–420.

Taylor, L. (2004). Reconstructing macroeocnomics: structuralist proposals and critiques to the mainstream. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Torvik, R. (2001). Learning by doing and the dutch disease. European Economic Review, 45(2), 285–306.

Tregenna, F. (2011). Manufacturing productivity, deindustrialisation and reindustrialisation, UNU-WIDER, Working Paper No. 2011/57.

UNCTAD. (2006). Investment policy review: Colombia. Geneva: United Nations Press.

UNCTAD. (2014). Manufactured goods by degree of manufacturing. Freely available for download from http://unctadstat.unctad.org/EN/Classifications.html.

Acknowledgments

We thank Diego Guevara, Miguel Uribe, Stephen Kinsella for their valuable comments. All errors remaining are ours. The authors gratefully acknowledge funding support of the Institute for New Economic Thinking.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Botta, A., Godin, A. & Missaglia, M. Finance, foreign (direct) investment and dutch disease: the case of Colombia. Econ Polit 33, 265–289 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-016-0030-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-016-0030-6