Abstract

Since 2012 the Italian Government made several steps to repay its commercial debts. By using a composite dataset, we evaluate the effect of these policies on the financial performances of a representative sample of Italian firms. We distinguish between firms beneficiaries of these repayments, those that were not repaid, although they had a legitimate right, and those that did not have commercial relations with the General Government. We find that receiving money had a significant positive impact on firms’ financial position.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

1.1 The Trade Debts of the Italian General Government

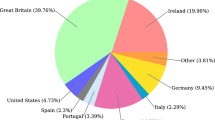

There is no official estimate of the total amount of trade debt of the General Government (GG) in Italy. According to estimates released by the Bank of Italy in its Annual Report, it was about 4.8 % of GDP in 2013, down from the peak of about 6 % in 2012.Footnote 1 Based on the data released for the Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP) notification, Italian GG’s trade debt is the largest in the Euro Area both in absolute terms and as a share of GDP: relative to GDP, the second largest share is recorded in Portugal (2.2 %), followed by Finland, France (both at 2.1 %) and Germany (1 %). Moreover, according to a survey conducted by Intrum Justitia, the average payment delay (in addition to contractual agreements) of the Italian Government is 90 days, compared to 4 days in Finland, 10 in Germany, 19 in France, about 70 in Portugal; in Greece is recorded the largest delay, well above 100 days.

There are many reasons for such trade debt accumulation, mainly occurring at local-government levels. Many municipalities faced severe financial constraints, mainly due to the Internal Stability Pact they had to comply with. This pact imposed severe limits to the timely reimbursement of local Governments creditors (Chiades and Mengotto 2013). In addition, at all government levels, until 2012 an implicit incentive for not paying on time suppliers was that trade debts were outside the Maastricht debt’s definition and had consequently very low priority. Only in July 2012 Eurostat slightly changed the rules so that credits released without recourse to financial intermediaries became part of the debt definition for the EDP notification.

On the side of the firms, there was a growing concern that GG’s repayment delays could worsen their economic prospects. This worry was aired by Confindustria (the main organization representing Italian manufacturing and services companies) in January 2012 with the launch of a program called “Progetto Confindustria”. It asked for the payment of at least 60 billion of GG’s trade debt, under the rationale that it would have made liquidity conditions less binding and investment more appealing for the firms having commercial relations with the GG. A further second-order effect should have benefited the firms without trade relations with the GG, that dealt with GG’s suppliers.

The Italian government devoted an increasing attention to the issue. Since the end of 2011, in order to alleviate financial problems of the firms and contribute to restore economic growth, the Parliament approved several laws to speed up the payment of Government’s outlays and relax the liquidity conditions for the firms.

In 2012 several laws provided money for the repayment of existing debt and simplified the bureaucratic procedures of payments. Indeed, in the Italian legislation, the GG can pay a bill only under strict formal conditions and, as a general rule, a credit can circulate in the financial market only if the debtor issues a “certification” to recognize its debt. Whilst in the previous years the release of the certification was a formal (but heterogeneous) procedure, in 2012 a decree law (Ministerial Decree, 22-05-2012) standardized and simplified the process.

However, standardizing the certification process was not enough to reduce the outstanding debt. Therefore some laws enacted in 2013 provided resources (25 billion available in 2013 and 16 billion in 2014) to public bodies for the payment of outstanding commercial debts overdue at the end of 2012. The policy maker had the double aim of repaying existing commercial debts and adopting a new approach based on timely debt repayments, that could foster a climate of mutual trust between GG and its suppliers.Footnote 2

According to Government’s estimates, the repayment policy of 2013 was expected to increase the GDP by 0.2 % in 2013, 0.7 % in 2014 and 0.3 % in 2015. The estimates by the Bank of Italy and Confindustria were more cautious, but nonetheless projected a GDP growth of 0.5–0.7 % in 2 years and 1 % in 3 years, respectively. The projections strongly depended on the speed of reimbursements and on firms’ utilization of the repayments. In particular, the effect on GDP growth would have increased with the share of repayment used for new investment.

1.2 The Aim of the Paper

Understanding whether these policies relaxed the financial conditions for the firms having commercial relations with GG is crucial to shed light on the performance of the whole Italian economy, the third largest in the Euro Area. We therefore evaluate the impact of the reimbursements on the Italian companies, by using a yearly survey conducted by the Bank of Italy on a representative sample of Italian firms with at least 20 employees, merged with financial information provided by banks to the Bank of Italy in its role of authority in charge of bank supervision. With the available data, we can measure the effects on firms’ performances until the end of 2013.

Because the primary aim of the policies was to provide firms with funds to relax their liquidity constraints, we look at their effects on some financial variables.

We find that receiving money had a significant positive impact on firms’ financial position, reducing their needs to assign credits to financial intermediaries and the probability of default on part (or all) of their debts. To some extent, also firms not receiving money might have benefited from the policies, through accessing the factoring market to sell their trade credits, without increases of the interest rate charged for the service.

We provide detailed evidence that the timing and the structure of the policies examined rule out any bias in our results caused, for example, by sample selection: indeed, the policies were completely unexpected and the target credits were due much time before policies were introduced.

This paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 provides some details on the GG’s trade debt legislation. Section 3 illustrates the modeling techniques we applied to estimate the policy effects. The data and some descriptive statistics are presented in Sects. 4 and 5, respectively. Section 6 shows the results. Section 7 provides some conclusive remarks.

2 The Existing Legislation

As in other countries, in the Italian legislation a payment from the GG must be legally authorized. Furthermore, to freely circulate in the financial market, GG’s commercial debts in general require a formal “certification”, with which the debtor recognizes the existence of the debt, its exact amount and that it can be claimed by the creditor. Certification is fundamental for debtors and creditors alike, because it gives the possibility of postponing the payment to the former and the access to credit lines from banks to the latter.

At the same time, because the GG always repays its debts, even if late, selling goods and services to GG was traditionally regarded as an opportunity of profits for firms and financial intermediaries. This view changed during the last economic crisis, since liquidity constraints have become increasingly more severe for firms.

For public bodies, having commercial debt was more convenient than borrowing money to pay their suppliers in cash because the former was out of the debt as defined in the EDP notification (it was only a memorandum item). This advantage lasted until 2012, when rules slightly changed and debt released without recourse to intermediaries became part of the debt definition according to the Maastricht treaty. Indeed, release to the market can be done either on a “without- recourse” or “with-recourse” basis. In the first case, the factor assumes the default risk, because it does not have recourse against the firm in case of default and accordingly charges higher interest rates for the service. In the second case, the factor has a claim against the seller for payment deficiency.

According to the Bank of Italy, in December 2013 8 billion were released without recourse to financial intermediaries (instead of 10.5 at the end of 2012; Bank of Italy 2014).

For a long time, certification was released on the basis of heterogeneous documentation requirements, often left at debtors’ discretion, in particular for the case of local authorities. This discretionary power was increasingly exercised as the constraints of the Stability and Growth Pact became more binding during the crisis. Aware of the slow pace of payments caused by this discretionary power, the Government made several steps to make it easier for firms to be paid: some steps aimed at facilitating debt certification by the debtor, others provided directly creditors with cash. In what follows, we describe the most relevant policies in chronological order, starting from 2011.

The Stability Law for 2012, issued at the end of 2011, made it compulsory for local-government entities to certify credits within 60 days, if requested by the creditor, and favored factoring towards the State-owned SACE company. The law turned out not to be effective: non-compliant public entities were not sanctioned, thus the number of certifications did not increase as an effect of the law.

A further attempt to relax the tight constraints imposed to GG’s creditors came few weeks later in January 2012, with the Decree Law 1/2012 (converted into Law 27/2012). The decree allocated 5.7 billion euro to regulate part of the Ministries’ trade debts either in cash or by assignment of government securities (if requested by the creditor). According to official figures, less than 3 billion were actually disbursed (only 15 million in the form of government securities). The difficulties faced by firms to obtain the credit certification were among the major reasons for the failure of the policy.

Therefore, four different measures were adopted in May 2012 to make it possible to obtain the certification for firms: two of them standardized the certification process using an Internet-based procedure. The standardized certification also asked the debtor to define a deadline for debt repayment within the next 12 months, but forbade the creditor to sue the debtor in the meantime. The third measure allowed firms to compensate between trade credits and fiscal debts, while the last one made banks advances easier by using a special fund (Fondo di garanzia per le piccole e medie imprese). These four measures (which we label collectively as “standardization policy” from now on) were an important step forward with respect to the existing practices, but, as it could be foreseen since their adoption, several exceptions could make the certification difficult to obtain.Footnote 3

As soon as the measures above were approved, another Government’s move to improve the economic agents’ expectations and promote trust in commercial relations towards the GG was the commitment to approve the Late Payment Directive of the European Union (Directive 2011/7/UE) by the end of that year. This policy was the only one announced by the Government, whereas the others were unexpected (this is quite important for the rest of the paper). On January 1st, the new rules of the Directive came into force: according to it, the deadline for trade debt payment is 30 days, with few exceptions (basically confined to the Health System, where it is extended to 60 days).

Because of the inability to reduce the stock of the outstanding commercial debt with the previous measures, in 2013 the Government adopted a completely different approach: on the one hand the bureaucracy was further simplified (e.g., differently from the standardization policy, no ISP-related exceptions were allowed to local bodies), on the other hand substantially more funds were injected into the economy (we label this policy as “repayment policy” from now on). More specifically, in April 2013 the Government approved a new bill for the payment of trade debts due at the end of December 2012, without any reference to the certification release. It is worth emphasizing that the eligibility criteria had to be met much earlier than the law was enforced (i.e., firms could not self-select to be treated by the policy). The total funds amounted to 40 billion, later expanded to 47, of which about 25 in 2013 and 16 in 2014 for trade debt and 6.5 for fiscal reimbursement.

Two points of this policy are relevant. The first is the provision to public entities of a strict timetable of deadlines that could induce fines for non-compliant public managers.Footnote 4 A second important aspect is the payment-priority rules: the first debts to be paid were those not released without recourse, according to debt seniority (following the principle of first-in-first-out, FIFO).Footnote 5

Many obstacles that hampered the previous reforms were removed by the following features of the new law: (i) the largest-than-ever amount of money allocated, (ii) the flexibility in the allocation of funds within the GG sub-sectors, (iii) the easiness of the certification procedure, (iv) the strict FIFO-like payment rule, (v) the absence of exceptions related to public-finance sustainability, (vi) non-compliant behaviors by public managers sanctioned by fines.

On the other side, the most relevant drawback was that, although large in absolute terms, the funds allocated were insufficient to repay the total overdue amount, with the consequence that some firms eligible to obtain money eventually did not get it.Footnote 6

These features determine that firms were eligible to benefit from reimbursement policies according to tightly defined criteria that were verified 4 months before the policy took place: it makes sure that the treatment is exogenous.

For the future, the prevention of GG expenditure arrears may be obtained by drafting an expenditure budget based on a correct medium-term fiscal framework, that encompasses all the main sources of risk. More specifically, a successful plan must take into account all the levels of government and any source of external constraints, such as supranational agreements limiting public spending (Flynn and Pessoa 2014). More specific to the Italian case, D’Aurizio et al. (2015) argue that significant improvements could be obtained by granting funds to local governments under the strictly conditionality that they are used one-to-one for reducing the outstanding stock of trade debts, in order to discourage their utilization for the reimbursement of current or new ones.

We add for completeness that further funds were allocated in 2014, but, as discussed in Sect. 4, our data do not cover this period.Footnote 7 Below we summarize the timeline (in boldface the policies of interest for our paper).

2012 | 01/2012 | 05/2012 | 07/2012 | 10/2012 | 04/2013 | 07/2013 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Certification compulsory | Debts for Ministries | Standardization policy | Maastricht debt definition | Implementation of standardization | Repayment policy | Implementation of repayment | Further measures not examined in the paper |

3 The Estimation Strategy

The reforms described in Sect. 2 allow a tight evaluation of the policies occurred since 2012. In this section we first briefly review how to identify and then how to estimate their causal effect.

Let us start with the simplest possible setup, with two groups of firms and two periods, before and after the policy. Of course, only the firms with commercial relations with the GG were potential targets of the policies (treated), whereas the other firms are defined as control group. Throughout the paper, we take the perspective of the policy introduced in 2013. Therefore, within the treated group, the firms that received money should be distinguished from those that did not receive it, although they had a legitimate right. This is a direct consequence of the FIFO approach. Our aim is to contrast the evolution of the outcome of the treated firms against that of the control firms. To do this, we use the well-known Difference-In-Differences (DID) technique. It evaluates the within-groups outcome difference, after and before the policy (the “-In-Difference” part of the technique) and takes the difference between these components (the first “Difference-” part) as the causal effect of the policy (see Imbens and Wooldridge 2009 for a survey of recent treatment-evaluation literature). The rationale for the approach is that, if the model is correctly specified and the evolution of the outcome would have been equal across the two groups in the absence of the policy (the so-called common trend assumption), the difference of the outcome between the two groups after the policy should be different only because of the policy.

More formally, we define \( T \in \{0,1\}\) and \(G \in \{C, D\}\) as respectively the time and group indicators and \(y_{i,T}\) as the outcome of interest, for a random sample composed of \(i=1,\ldots ,N\) individuals. The time indicator \(T=0\) refers to pre-policy periods, whereas \(T=1\) indicates those post-policy. The group indicator \(G=C\) indicates the control group and \(G=D\) refers to the treated units. Under common trend assumption, if the error term is independent from the variables of interest, i.e. \(E \perp G \) (usually referred to as mean independence treatment, implying also the ignorability of treatment), the saturated model without covariates for a generic member of any of groups can be written as:

where \(\gamma \) captures possible differences between the two groups prior to the policy change, \(\beta \) captures aggregate factors that would have caused changes in the outcome even though the policy would have not been implemented and \(\tau _{\textit{DID}}=E[(y_{D,1}-y_{D,0})]-E[(y_{C,1}-y_{C,0})]\) identifies the treatment effect and can be estimated by OLS.

Possible extensions are worth mentioning for later purposes: (i) the exploitation of the panel structure of the data, (ii) the introduction of covariates, (iii) the extension to more periods and/or more treatments.

With respect to the panel structure, a fixed-effect estimator would be equivalent to estimating Eq. 1. A possible solution would then be assuming the unconfoundedness, given lagged outcomes, but in this case there might be a problem if lagged outcomes and error terms are correlated (see Imbens and Wooldridge 2009). Nonetheless, we will explore this alternative too, as a check of our results in Sect. 6.

Somewhat more problematic is the extension to covariates, because a potential pitfall arises when characteristics of treatment and control groups change as a consequence of treatment. To avoid biased estimates of the causal parameter associated with this risk, one should contrast the two groups over dimensions that are unaffected by the treatment (see Angrist and Pischke 2008): suggested covariates should thus be out of the decision set of the firms, without feedback from treatment or fixed at the period preceding the policy. In line with this suggestion, our covariates are referred to 2011 to prevent them from being affected by the treatment.

Finally, it is interesting to generalize the approach to two periods and three groups (two of which are treated), consistently with the policies described in Sect. 2. If we define the two treated groups as G\(_{1}\) and G\(_{2}\), the following regression (again, for a generic member of any of groups)

identifies \(\tau _{1,\textit{DID}}\) and \(\tau _{2,\textit{DID}}\) as the causal parameters of the policy with the very same meaning as in Eq. 1, under the main assumptions of the common trend and exogeneity (see Appendix 2 for the derivation).

All the above identification results are based on the strong assumption of common trend and ignorability of the treatment. As for the former, it may be the case that some of the covariates are themselves subject to a trend, which might be different between treated and controls, making the treatment effect heterogeneous: the proposed solutions involve the interaction between \(\tau _{\textit{DID}}\) and covariates that induce heterogeneity in the policy effect (Gibbons et al. 2014) or weights to make the distribution of the covariates between treated and control equal (Abadie 2005).

The common trend hypothesis may be violated also because the outcomes derive from individual-specific trends, independent of the policy and of the covariates. In these cases, if this individual-specific trend is purged, the estimation procedure works perfectly well: everything is similar, apart from the fact that data first differencing will eliminate a linear individual specific trend (the approach is called Difference-In-Differences-In-Differences, DIDID; see Wooldridge 2001). Following the existing literature, the evidence that we produce in favor of the common trend assumption is the graph of characteristics across time by groups and a test for a significant difference in their rate of growth before the policy is introduced.

We carried out robustness check of our results against these possible drawbacks. They produced estimates closely aligned with those illustrated in the paper (not shown for brevity, but available on our website), unless specified.

The ignorability is not an issue in this analysis because the eligibility criteria were tightly specified by the law and the requisites were those existing 4 months before the policy took place (the treatment status is pre-determined with respect to the outcome, as discussed in Sect. 2).

4 Data Sources

In this paper we use firm-level information from two Bank of Italy’s yearly surveys, matched with credit-line information (compulsorily provided by banks) from administrative datasets. In this way, we can evaluate the policies over a wide range of indicators. Section 4.1 describes the surveys, Sect. 4.2 the administrative data.

4.1 The Business Survey Data

The main data sources that we use for the firms are the Bank of Italy’s yearly survey on Industrial and Service firms (Bank of Italy 2013b, Invind in what follows), and the Business Outlook Survey (Bank of Italy 2013a; Sondtel from now on).

The main purpose of Invind is evaluating the overall trends of investment, revenues and employment for firms with 20 employees and over, representing a substantial share of the totals of the whole population of Italian firms (over 70 % for non-construction industry, slightly less than 60 % for non-financial private services). Sondtel is instead a precious instrument for the assessment of the cyclical position of the Italian enterprises. Both datasets contain a wide set of indicators that help model the response to the policies.

Since 2002, both surveys have been carried out on the same representative sample of firms. The target population is represented by firms belonging to the non-construction industry (33,057 firms) and to the non- financial private sectors (33,449 firms). The sample is composed on average by 4000–4100 units for every edition. A specific short questionnaire covers construction firms with 20 employees and over since 2006. In this paper we do not analyze them, because key information is somewhat different from that collected in the main survey.

The firms participating in a given edition are always re-contacted in the following one. Firms leave the sample if they bankrupt or refuse definitively to participate in the survey. They leave the sample temporarily if they do not belong to the target population at the moment of the interview or they have temporary difficulties to provide the data requested.Footnote 8 The sample representativeness is preserved by replacing firms leaving the sample with others that are similar to them in terms of size, type of activity and headquarters’ location.

A set of weights make the sample representative of the target population.

The data for the Invind edition referring to the year t are collected between January and April of the following year \(t+1\). The questionnaire is composed by a fixed and a variable part. The fixed part contains general information on firm structure, as well as annual data on investment, employment, revenues, operating result, capacity utilization and financing. The variable parts cover different topics each year, which are the object of detailed cyclical or structural analyses.

The data for the edition of Sondtel referring to the year t are collected between September and October of the same year. The survey questionnaire is considerably shorter than that of Invind. It aims at collecting categorical ordered information about the perspective trends of employment, investment, revenues and orders. It also contains short parts, variable according to the analytical needs suggested by the economic outlook.

In the last few years, a growing attention has been paid to firms’ trade credits. Indeed, on the one hand the issue has become more relevant whilst, on the other hand, no official data has been available regarding the topic. Therefore, an extensive section of the Invind questionnaires covers firms’ trade credits, with a focus on those towards the GG. Firms are asked to provide the end-of-year amount of total trade credit receivables outstanding and, specifically, the amount due from the GG. They also indicate some non-monetary characteristics of trade credit, such as contract terms, share collected with deferment and average length of the delay.

Furthermore, the 2013 edition of the Sondtel (Bank of Italy 2013a) asked firms eligible for repayment according to the rules introduced in 2013 (see Sect. 2), whether they had been repaid in the first 9 months of the year.

4.2 The Administrative Data

We extracted additional information on firms from the archives of bank-level data collected for supervisory purposes. Data regarding firm-bank relations come from the Central Credit Register (CCR) database, managed by the Bank of Italy. It is an administrative database, which records each month detailed financial information on credit lines provided by Italian banks to firms and individuals. The reference population for the information is made of all the credit lines exceeding the minimum threshold of 30,000 euro. The threshold is determined by summing all the credit lines granted by a bank, grouped into three main categories:

-

1.

short-term lines of credit;

-

2.

collateralized credit lines, mortgages, etc.;

-

3.

advances, etc.

Data are also available on:

-

1.

Credit quality, i.e. whether each credit line granted is past due, restructured or substandard (Bank of Italy 2011). The database registers bad credit lines of any amount.

-

2.

Firms’ trade credits assigned to financial intermediaries, with the distinction whether the assignment is with or without recourse. Trade credits assigned through factoring can also be separated from the rest.

The main purpose of the register is to provide banks with comprehensive information to assess the creditworthiness of their customers and to analyze credit risk, with the final aim of improving credit quality and, as an aftermath, financial stability.

The nature of administrative database, on which data (mainly collected for supervisory purposes and highly confidential) are compulsorily filed by banks, provides the advantage of lack of unit-level and item-level non response.

In addition, the 229 most relevant Italian banks by the size of their credit lines and the number and diffusion of their branches have to file quarterly information on the interest rates charged on each credit line above the threshold of 75,000 euro.

A wide range of measures are set up to insure the highest possible data quality level. First of all, the financial institutions are obliged to verify the correctness of the information they receive and to rectify any error, according to specific procedures. The absence of rectification implies that the data recorded are correct. The CCR can ask a financial intermediary to check particularly sensitive items: in such a case the institution must answer the request as soon as possible. The data we use are the most updated ones available at the end of March 2014.

4.3 The Integrated Archive

By using the uniquely identified tax code (available in all the sources), we built an integrated archive containing the 2010–2012 editions of Invind, the 2010–2013 editions of Sondtel and the corresponding CCR information. For every firm participating in the survey, we matched all the data available from the CCR for the 2010–2013 period. On average, 95 % of the tax codes found in Invind or in Sondtel are exactly matched in the CCR archives, without significant variability across the different years, class size, sectors of activity, geographical location of headquarters.

5 Descriptive Statistics

5.1 The Evidence from Survey Data

Our data are taken from 7 consecutive editions of the Invind and Sondtel surveys carried out between 2010 and 2013. On average, 4100 firms are observed on each occasion and 86 % of those participating in a survey are still found in the next one; 70 % of the firms belong to the industrial sector, 30 % to the non-financial services (see Table 1).

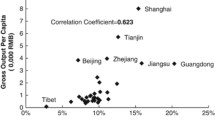

In the years 2010–2012, 25 % of firms in our sample had commercial relations with the GG. This share is lower for manufacturing firms (around 12 %) and rises to 60 and 37 % for firms operating in the energy and services sectors, respectively. The transitions between the two states of having or not trade relations with the GG are quite rare and affect 5–6 % of the sample units in the period considered (half of cases are firms ceasing to deal with GG, the other half is the reverse transition).

The average share of revenues from commercial relations with the GG over total revenues is around 20 % for firms with trade relations with the GG. The trade credit towards the GG amounts to around 10 % of total trade credit. Since the average share of revenues with the GG amounts only to 5 % when computed over all firms, this is a clue that the propensity to use trade credit in the business transactions with GG is higher than average.

The Sondtel survey conducted between September and October 2013 asked firms whether they were eligible to receive repayments thanks to the repayment policy and whether they actually received it in the first 9 months of 2013. From these questions, we distinguish three groups of firms on the basis of an indicator of commercial relations with the GG according to the eligibility to receive money thanks to the 2013 laws and on whether such money was actually received. Since the payment was based on credit seniority (FIFO-like criterion), the indicator will also approximately reveals the duration of commercial relations with the GG.

It turns out that almost 60 % of the eligible firms received some repayments; the share tends to grow with firm size (Table 2). As seen in the last column of the table, repayments are estimated to represent only 13 % of the end-of- 2012 total trade credit outstanding towards the general government.

The main characteristics of the three groups of firms are summarized in Table 3. We see that the differences in size (in terms of number of employees and average yearly revenues) among the three groups are not statistically significant. According to economic sector and headquarters’ geographical area, the firms without commercial relations with the GG are broadly similar to those eligible for reimbursements (apart from the sector of energy and mining and the area of Central Italy). As for performance variables, the differences we found do not appear to be economically relevant, even if in few cases they are statistically significant.

5.2 The Evidence from the Central Credit Register Data

We distinguish between financial indicators based on short-term liquidity needs and those concerning firms’ creditworthiness and present our results for the three groups of firms previously defined.

In all these indicators, the evolution preceding the policies is broadly similar across different groups, apart from a location shift. This is a first evidence, yet incomplete, supporting the idea that in the absence of intervention the evolution of the outcomes would have been equal across groups. In the next section we will provide further formal results in favor of the assumption.

The market for trade credit assigned by firms to financial intermediaries is a proxy of short-term liquidity constraints, according to the literature. During 2013, the repaid firms’ utilization of assignments slightly declined in the with-recourse market, whereas firms not repaid tended to sell their claims more actively (Fig. 1a). A similar pattern is shown in the without-recourse market (here the repaid firms’ activity climbed down from an end-of-2012 peak and remained flat during 2013, Fig. 1b). As for the net interest on factoring applied to repaid and not repaid firms (Fig. 1c), it decreased during 2013 and the spread between the two groups considerably narrowed.

The pattern of deteriorated credit provides an evidence of firms’ creditworthiness. During 2013, the share of substandard or restructured credit for repaid firms was much lower than that of firms still waiting for GG’s repayments at the end of September 2013 (Fig. 1d).

6 Results

6.1 The Modeling Approach

Our goal is to evaluate the impact of the Italian GG’s provisions enacted since 2012 to repay its trade debt towards firms.

In order to perform this evaluation, we define two treatment groups on the basis of the reimbursement policy enacted in 2013:

-

1.

the firms that were repaid during the year 2013 (G1);

-

2.

the firms that could receive money but were still waiting at the end of 2013 (G2).

The firms that did not have commercial relations with the GG form the control group.Footnote 9

We obtain more precise point estimates by running the model separately for the two treatment groups (once the control group and G1; once the control group and G2).

Since payments were made according to the seniority of trade debt, the two treatment groups also classify firms according to the duration of their commercial relation with the GG and as such the classification could also be used to gain insights about previous policies (indeed, this is possible since a transition matrix shows that the condition of commercial relations with GG is highly persistent). Our benchmark approach is a Difference-In-Differences (DID) (under the assumption that treated and control groups would have followed the same trend for the outcome in the absence of the policy), although we checked our results exploiting also a DIDID and panel estimators. Results discussed below are robust to these techniques (details are available on request).

Before proceeding we tackle some relevant issues. The first is the possible seasonality of financial data, which are available with monthly frequency. We purge the seasonal pattern by running separate regressions over the same month in different years (e.g., selecting January 2012 and January 2013 in one regression, February 2012 and February 2013 in a different regression and so on). In all our regressions we use at most 3 periods, for several reasons: first, we obtain more precise estimates against bias; second, we have a more balanced sample between treated and control groups; third, we avoid any problem related to precision of estimates in terms of efficiency (see Bertrand et al. 2004).

Our dependent variables are sometimes in logarithms, so that in these cases we evaluate a percent change caused by the policy, i.e. a DID of the form: \([ln(yD,1) - ln(yD,0)] - [ln(yC,1) - ln(yC,0)]\) (for a discussion, see Mullahy 1999).

The typical set of covariates (defined as Z below) that we use are dummies for: sector of activity, months (where appropriate), year, region, quartiles of sales and firm size, measured by using a categorical ordered variable for number of employees (20–49, 50–199, 200–499, 500 and over). All firm-level data are relative to 2011 (before treatment takes place), so that policy coefficients are not influenced by the dynamic of the covariates.

We always estimate:

where \(T_i\) is a dummy variable taking value 1 after the policy change, G\(_i\) is a dummy taking value 1 for treatment group (once G1 and once, in a separate regression, G2) and T\(_i\)G\(_i\) is the interaction between the two dummies.

If the policies successfully relax the financial conditions of eligible firms, the access to the release market and/or the amount of released credits should be lower than for the control group (\(\tau _{i,\textit{DID}}<0\)). At the same time, the policies may have avoided defaults of creditor firms, in which case the treatment coefficient should be negative (\(\tau _{i,\textit{DID}}<0\)).

Since we run a great number of regressions, we opt for a synthetical presentation of our results, by a series of plots showing the time pattern of the coefficients of interest along with their confidence intervals.

We run several robustness checks on specific subsamples, identified by: firm size, sector of activity (both with the same categories used in the model), quartile of sales, geographical area of firms’ headquarters (North, Center, and South and Islands). This approach addresses the issue of possible heterogenous treatment effect (Abadie 2005).

As for the identifying assumptions, we first test whether the common trend assumption is credible. In order to do this we run a flexible regression, for the period preceding the policy change and cannot reject the null hypothesis that coefficients are equal across groups at standard confidence levels. These results, with the help of graphical evidence provided above, are strong arguments that common trend is a feature of the data.Footnote 10 Since the hypothesis is key for identification of the policy effect we will analyze it case-by-case in Sects. 6.2.2 and 6.2.3.

6.2 The Results for the Financial Indicators

6.2.1 General Background

It has been pointed out that Italian firms are often short of liquidity, but economically sound (Panetta 2013a, b). Their liquidity problems can be worsened by the large delay of GG payments, which can cause: (1) liquidity constraints, (2) lack of solvency induced by liquidity shortage, (3) less willingness by banks to lend because of (1) and (2).

At first, we focus on the possible impact of the policies on some liquidity indicators, such as assignment of trade credits to the release market, with a focus on factoring, and deterioration of firms’ total bank credits. The complete set of policy effects (DID coefficients) is plotted in Figs. 2, 3 and 4, along with their 10 % confidence intervals (total coverage), whereas point estimates for the months most relevant for the policy effects are in Tables 4 and 5.

Financial indicators (variation over 12 months before)—DID coefficients—10 % confidence interval. Weighed regressions representative of the whole population. Straight line Firm-level control variables relative to 2011: sector of activity, headquarters’ region, number of employees, quartiles of sales, government bond spread. a Access to the release market, b access to the release market—factoring, c share of defaulted debts over total debt

Financial indicators (variation over 12 months before)—DID coefficients—10 % confidence interval. Weighed regressions representative of the whole population. Straight line Firm-level control variables relative to 2011: sector of activity, headquarters’ region, number of employees, quartiles of sales, government bond spread. a Access without recourse, b access with recourse, c access without recourse (factoring), d access with recourse (factoring), e share of defaulted debts over short-term debt, f share of defaulted debt over long-term debt

Financial indicators (variation over 12 months before); avg. amount of factoring and agreed loans—DID coefficients—10 % confidence interval. Weighed regressions representative of the whole population. Straight line Firm-level control variables relative to 2011: sector of activity, headquarters’ region, number of employees, quartiles of sales, government bond spread. a Factoring without recourse, b factoring with recourse, c agreed loans; short-term, d agreed loans; long-term

For the release market, we study both the extensive margin (i.e., number of firms accessing the market) and the corresponding intensive margin (i.e., amounts traded). However, these results are partial equilibria, which are driven by the interplay of demand and supply curves. In the absence of any reasonable instrument to discern between the two, an exam of the new equilibria may be more revealing only if we use other external stylized facts. We attempt an interpretation of our results in this direction in Sect. 6.2.2.

Our results suggest that the policies enacted since 2012 were effective for the firms that were reimbursed by the 2013 policy, and hence had a relatively longer credit seniority, at least for instruments without recourse towards original creditor (who released the credit). Moreover, there could also be an indirect positive effect for firms still waiting to be reimbursed at the end of 2013.

We find an effect of the policies on the release market: starting from the second half of 2012, releases tended to decrease for reimbursed firms, whereas they increased for firms still waiting to be repaid, in particular for factoring (see Fig. 3a, c). Both groups of firms could access the release market by paying lower interest rates during 2013. As we will argue, such an effect could be the aftermath of the shift of the demand schedule for repaid firms and of the supply schedule (i.e., less binding conditions imposed by the banks) for those not repaid.

The credit deterioration of the reimbursed firms decreased from the end of 2012, as shown by Fig. 2c.

The coefficients for all the financial indicators examined are affected by greater uncertainty for the firms still waiting for reimbursements at the end of 2013, consistent (by the law of total variance) with a large heterogeneity of this group of firms.Footnote 11

The next two sections will provide more details on the effects of the policies on firms’ financial conditions. Section 6.2.2 will also discuss the main points raised by the economic literature on trade credit.

6.2.2 Firms’ Financial Constraints

As for financial constraints indicators, we first measure the policy effect on the access to the release market (Table 4; Figs. 2, 3, 4). In Italy, firms’ commercial activity involves the utilization of trade credit on a much more intensive scale than other advanced countries (Omiccioli 2004). A well-known role of trade credit in firm-bank relationships is the possibility for firms to use it as collateral to obtain bank loans. Therefore, we interpret the utilization of the release market of trade credits as a proxy measure of firms’ financial constraints. Our choice is bolstered by a rich literature on factoring, that is the main instruments used by firm to trade illiquid assets (such as their trade credits) into cash. It can be done either on a “without- recourse”, i.e. the factor assumes the default risk, or “with-recourse” basis, i.e. the factor has a claim against the seller for payment deficiency (see Sect. 2). In advanced countries, factoring is mainly done on a without-recourse basis (in Italy, for example, 69 % of all factoring was done in such a way in 2004).Footnote 12

Global data on factoring utilization in advanced countries suggest its potential advantage compared to traditional types of bank lending, under certain conditions (Klapper 2006). More specifically, factoring could finance high-risk firms by releasing their credits, since the factor underwrites only the risk of the released trade credit. The instrument could provide risky and small-sized firms with a way to finance their growth, thereby bypassing liquidity constraints derived from their lack of high-quality collateral. Benvenuti and Gallo (2004) argue that financially stressed firms have an above-the-average propensity to use factoring and support this claim with econometric evidence on a large sample of Italian firms.

These references support our hypothesis that reimbursed firms could decrease their utilization of the release market (mainly factoring) because of less pressing liquidity constraints.

Before looking at results, we briefly comment on the key common trend assumption. Focusing on the access to the without-recourse market, the graphical evidence of Fig. 1b supports such an assumption, since the frequencies of access to the market for the two groups of firms, either reimbursed or eligible but not reimbursed, are quite close until the end of 2012 and then start to diverge. The access to the factoring segment, not shown for brevity, features a similar trend.

A more formal argument is that the F-test for the null hypothesis of the equality of coefficients across all different groups is never rejected in a regression of each dependent variable on the covariates interacted with the group dummy. The test refers to the period preceding the first standardization policy, which was launched in May 2012. This is the standard test to support the validity of the common-trend assumption.Footnote 13

The results on the generic access to release in market are not statistically significant, but are in accordance with the indication of the literature, since the firms receiving money tended to decrease their access to the release market, (as shown by the DID coefficients, Fig. 2a), whereas eligible firms not receiving money tended to increase it. We obtain significant results for the specific without-recourse market (Fig. 3a), where not reimbursed firms increased their access by 3–4 % points as early as 2012. Point estimates for access to instrument with recourse are never statistically significant (Fig. 3b).

Since access to release market can take various forms, we focus on factoring, which accounts for over 90 % of all releases in our sample, paying more attention to that without recourse. Firms still waiting for money from the GG at the end of 2013 increased their access to factoring without recourse by 3.5 % points during the implementation of the standardization policy at the end of 2012, but remained stable at the level of 2012 during the payment policy of 2013 (see Fig. 3c), at the same time, the firms receiving money decreased their access to this market by 1.5 % points, but remained relatively stable between 2012 and 2013. The results for the access to the market of with-recourse factoring are in line with those relative to the whole with-recourse market and likewise not significant (Fig. 3d).Footnote 14

Looking at subsamples, the access without recourse is larger for big companies, and, to a lesser extent, for those headquartered in Southern Italy or operating in the services sectors.Footnote 15

Overall, these results show that the eligible firms not repaid increased their access to the release market, whereas those repaid decreased such access, with effects becoming significant since the second half of 2012, when the standardization policies could be actually implemented.

We can attempt to interpret these results going beyond the partial equilibrium. The first natural question is whether it is a consequence of a shift of the demand or of the supply-side schedule. With the data at hand, we cannot answer this question empirically. However, two arguments provide evidence in favor of one of the two sides. The first is given by a specific question in the Bank of Italy’s Business Outlook survey carried out in 2013, which asked firms to indicate the utilization of GG reimbursements: a substantial share of the reimbursed firms, slightly less than 50 %, used the money to pay their own trade debts or reduce their payables to the financial system. This is a clue that reimbursed firms might have decreased their demand for factoring. The second argument is based on a simple classical theoretical framework of demand and supply that allows us to make some comparative statics. Consider the equilibrium point E in Fig. 5. We see that the total amount factored without recourse by repaid firms declined during 2013 (Table 4). This may be consistent with a shift downward of the demand curve or an upward shift of the supply schedule. In the former case, we would observe a lower price as in D0, whereas in the latter case there would be a higher price as in S1.Footnote 16 Which is the most likely effect between the two? We run a DID on the discount rate for factoring to understand this: the discount rate for both groups in 2013 was lower than in 2012, although not at the usual significance levels (Table 4). Our results are not in contrast with a smaller demand for release instruments by firms receiving money and loosening supply conditions for those not receiving it. These findings might indicate that factors compensated the former group’s smaller demand with a larger supply to the latter group.

We are also interested in the intensive margin for the firms accessing the release market. We find that the amount of overall factoring was not significantly affected by the policy, regardless of whether firms received money or not: this derives from the invariance of factoring without recourse (Fig. 4a; Table 4) and the lower level of factoring with recourse (much smaller than the first component) during the standardization policy (Fig. 4b).

These results show that the policies were mainly successful for the firms that actually received money, when they used instruments that fully transfer the risk (i.e. without recourse). Firms not receiving money benefited from the policies mostly through less binding supply conditions. Since the 2013 repayments were carried out on a First-In-First-Out principle, they are a proxy for the seniority of the trade relations with the GG. Accordingly, the positive effect of the 2012 standardization policy can be ascribed to the fact that the firms with relatively junior credits wanted to avoid to be liquidity-constrained because of late payments and after the standardization policy rushed to assign their credits to financial intermediaries. The opportunity cost to release the credits would have been higher for firms whose credits had higher seniority.

6.2.3 Firms’ Creditworthiness

Firms’ long-run economic conditions could worsen because of debtors’ repayment delays, that eventually may even lead creditors to default.

In order to study this issue, we focus on the substandard or restructured credit lines, that can have short-term variations and as a consequence may be influenced by GG’s trade debt policies.Footnote 17

As for the common-trend assumption, Fig. 1d clearly shows that the patterns of credit deterioration begin to diverge across groups starting from the end of 2012, thus supporting the assumption. A similar pattern, omitted for brevity, recurs for the deterioration of long-term loans. The same indication is provided by the F-test, run in the same way as that shown in Sect. 6.2.2 for the access to the without-recourse market with similar results.

From Fig. 2c it is clear that the share of deteriorated bank debt became significantly lower for the reimbursed firms, whereas it did not have significant variations for those not yet repaid at the end of 2013.

This general result does not distinguish between short-term and long-term loans. When we split the two, the pattern of deteriorated long-term credit (Fig. 3f) is very similar to the general one, since about 85 % of total debts are long-term. The benefit for them became significant since October 2012 (initial reduction by 1.5 %), when the standardization of certification was actually implemented (Table 5). The reimbursement policy reinforced this positive effect during 2013 (with an additional 1 % reduction with regards to 2012). Because the definition of substandard credit is in part discretionary, these positive effects may signal both an improvement of firms’ actual conditions and of banks’ perceptions of their creditworthiness.

On the other hand, the policy did not affect the deterioration of short-term credit (see Fig. 3e). A likely explanation of this result is that the short-horizon prediction of credit deterioration is very reliable, regardless of the evaluated policies, and therefore only safe short-term loans tend to be granted (the fact that the share of substandard or restructured short-term loans, amounting to less than 4 %, is lower than that for long-term loans supports this intuition).

Interesting distinctions arise when we take into considerations the heterogeneity of the effect. Indeed, among firms that received money, those of medium size, medium sales level, located in the North or South or operating in the services experienced an above-the-average effect; among the firms that did not receive money, the not significant general effect becomes significant for firms with large sales, operating in the North and in the manufacturing sector.

Another reason for concern was that financial intermediaries would be less willing to lend money, because the delay of GG payments could put firms at default risk. Since more than 95 % of firms have some forms of bank loans, we only consider the intensive margin. We consider the amount of short- and long-term agreed loans (Fig. 4c, d; Table 5). In general, the policies had no significant effects on the amount of short-run and long-run agreed loans. The sample splits reveal that, among firms receiving money, the smallest ones in terms of size or sales and those operating in the manufacturing sector benefited by superior short-term loans as an effect of the policy, whereas the largest ones among those not receiving money received a positive effect. The splits do not reveal any significant sub-effect for long-run loans.

7 Conclusions

Our paper estimates the effects of the laws enacted in Italy since 2012 to accelerate the reimbursement of General Government’s trade debts towards firms. More specifically, we analyze their effects on firms’ financial conditions and longer-term economic perspectives.

By exploiting the data of the Business Outlook Survey on Industrial and Services firms, carried out between September and October 2013, we could distinguish three groups of firms: (1) those eligible to receive the repayments, which actually got it in the first 9 months of 2013; (2) those eligible to receive the repayments, that were still waiting for them when they were interviewed; (3) those without trade relations with the General Government. These data were matched with Central Credit Register information in order to assess firms’ financial conditions, as well as other economic indicators.

The Difference-In-Differences (DID) approach we used shows that the firms repaid improved their financial outlook, without significant effects on other economic indicators. More specifically, the reimbursed firms improved both their short-term financial position (they made less use of factoring and, more generally, of credit assignment without recourse) and their longer-term relationship towards the banking sector (the deterioration of their credit lines significantly decreased). We even show an indirect positive effect, albeit more contained, for firms eligible for refunds but still waiting for them at the end of 2013, which might have benefited from lower interest rates when they tried to release their trade credits in the market. Our results are robust to different techniques. Some interesting distinctions arise across different sub-samples.

Notes

According to the notification valid for the Excessive Deficit Procedure - supervised by Eurostat - the trade debt not included in the Maastricht debt and related only to current account expenditure was 3.3 % of GDP in 2013, from 3.9 % in 2012. The references to this report and to all the others mentioned later are collected in Appendix 1.

In addition to these measures for existing debt, a European Directive imposed strict rules for the payment of the invoices (30 days, apart from few exceptions, basically related to health provisions, for which the period was extended to 60 days). Italy was the first country to adopt the Directive (D.LGS. 192, Nov. 2012) and made it effective since the beginning of 2013.

The most relevant hurdle related to public finance was the Internal Stability Pact (ISP), which was arguably one of the factors responsible for the trade debt accumulated by local governments. To respect the European fiscal rules, the standardization policy allowed indebted public bodies to refuse to release the standard certification whenever it hampered the respect of the ISP. In this case, the certification could be released without a deadline, with serious difficulties for firms to assign their credits to financial institutions. Likewise, the National Health System was not obliged to release the certification if the repayment of its trade debt was not in line with their public finance projections. Other limitations were more technical. Moreover, the lack of credible sanctions for non-compliant public entities made it even more difficult for firms to have their credits certified.

For instance, one of them regarded the registration on the Internet platform for the release of the certification, introduced in 2012, or the publication on a website of the list of the existing debts.

The creditors’ list was to be made public by the debtor and was also valid as debt certification; on the other hand, firms could ask for a list integration after its completion.

Further obstacles were the many regulations needed for the law to be completely effective and the fact that many public managers preferred not to use the funds, since they perceived the rules as too binding.

The Government passed a bill providing for (a) monthly monitoring of payment times, partly through the use of e-invoicing; (b) the allocation of about 9 billion to speed up the payment of arrears (supplementing the previous measures); and (c) provisions to facilitate the transfer of claims to the banking system. As discussed in Sect. 4, our data do not cover this period.

The most frequent reason for firms no longer belonging to the target population is that their size drops below the 20-employee threshold.

Notice that this definition encompasses a different approach where firms already repaid (G1) are the treatment group and those not yet repaid (G2) the control group (see Appendix 2 for a proof).

Furthermore, suppose that common trend were not verified in our data, we would reasonably expect firms having commercial relations with the GG to be more at a disadvantage than those without commercial relations with it, because of more binding conditions imposed to them (as described in Sect. 1). It follows that the evolution of the former firms would have been even worse and our estimates would be conservative (downward bias of the policy effect).

Some of the heterogeneity may be overcome by modeling firm-specific trends (i.e. by using DIDID instead of DID), which can produce in some cases clearer patterns for the firms not repaid, without changing those relative to the firms repaid.

These definitions highlight the role of the moral hazard in factoring (Sopranzetti 1998), by which the propensity to without-recourse factoring increases with trade credit quality. Firms with a high bankruptcy probability may be unable to factor their entire trade credits pool and in general they will be able to factor without recourse their most reliable trade credits and with recourse those of intermediate quality.

These results are available on request, since they are not shown for brevity.

We ran a robustness check (not shown for brevity) by dropping the accesses to the release market specifically due to trade credits towards the GG, obtaining broadly similar results.

We obtain the same results if we focus on trade credit towards the national health service. This is relevant, since this sector accounts for the largest share of GG’s trade debts and is also one of the most financially constrained.

Of course both curves would probably move: this is the case of S0 where they move such that one offsets the other (i.e., the price is constant). However, as long as price increases we will talk of a larger shift in the supply curve.

These variations are not necessarily found for bad debts, which tend to persist on banks’ balance-sheet for years (Bank of Italy 2012).

References

Abadie A (2005) Semiparametric difference-in-differences estimators. Rev Econ Stud 72(1):1–19

Angrist J, Pischke J (2008) Mostly harmless econometrics: an empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Bank of Italy (2011) Centrale dei rischi - istruzioni per gli intermediari creditizi (Italian version). Circolare 139 della Banca d’Italia (aggiorn. n. 14 del 29 aprile 2011), II.23

Bank of Italy (2012) Statistical appendix (Italian version). Annual Report, 127

Bank of Italy (2013a) Business outlook survey of industrial and service firms (year 2013). Supplements to the Statistical Bulletin 56

Bank of Italy (2013b) Survey of industrial and service firms (year 2012). Supplements to the Statistical Bulletin 38

Bank of Italy (2014) Annual Report for 2013-May 2014

Benvenuti M, Gallo M (2004) Perché le imprese ricorrono al factoring? il caso dell’Italia. Bank of Italy’s Working papers (518)

Bertrand M, Duflo E, Mullainathan S (2004) How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates? Q J Econ 119(1):249–275

Chiades P, Mengotto V (2013) Il calo degli investimenti nei Comuni tra Patto di stabilità interno e carenza di risorse. Bank of Italy’s Occasional papers (210)

D’Aurizio L, Depalo D, Momigliano S, Vadalà E (2015) I debiti commerciali delle Amministrazioni Pubbliche: un problema ancora irrisolto. Bank of Italy’s Occasional papers, forthcoming

Flynn S, Pessoa M (2014) Prevention and management of Government expenditure arrears. Technical Notes and Manuals, International Monetary Fund

Gibbons CE, Serrato JCS, Urbancic MB (2014) Broken or fixed effects? Working Paper 20342, National Bureau of Economic Research

Imbens GW, Wooldridge JM (2009) Recent developments in the econometrics of program evaluation. J Econ Lit 47(1):5–86

Klapper L (2006) The role of factoring for financing small and medium enterprises. J Bank Financ 30:3111–3130

Mullahy J (1999) Interaction effects and Difference-in-Difference estimation in loglinear models. NBER Technical Working Papers 0245, National Bureau of Economic Research Inc

Omiccioli M (2004) Il credito commerciale: problemi e teorie. Bank of Italy’s Working papers (494)

Panetta F (2013a) Banks, finance, growth. Speech held at Associazione per lo Sviluppo degli Studi di Banca e Borsa, in collaboration with Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore of Milan

Panetta F (2013b) Credit and the financing of firms. Speech held at Federazione delle Banche di Credito Cooperativo Lazio Umbria Sardegna

Sopranzetti BJ (1998) The economics of factoring accounts receivable. J Econ Bus 50:339–359

Wooldridge JM (2001) Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data, vol 1. MIT Press Books The MIT Press, Cambridge

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We thank Luigi Cannari, Giovanni D’Alessio, Tullio Jappelli, Francesco Manaresi, Sandro Momigliano, Enrico Rettore, Paolo Finaldi Russo, Paolo Sestito, Emilio Vadalà and the participants to the ICEEE conference held in Salerno in January 2015 for their useful suggestions. All the routines and results are be available at the webpage: http://sites.google.com/site/domdepalo/. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not imply any responsibility of their institutions.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Reports

-

1.

The EDP notification data can be found at http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/government_finance_statistics/documents/Note_on_AF.71L-Apr_2013.pdf.

-

2.

Intrum Justitia is a European company in the sector of management and recovery of credit. The report is available at http://www.intrum.com/Documents/Italy/EPI/2013/2013_05_16_EPI2013.pdf.

-

3.

The Eurostat decision on the Maastricht debt definition including trade credits is published at http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/government_finance_statistics/documents/Statist.record.of_some_operations_rel.to_trade_credits_i.pdf.

-

4.

“Progetto Confindustria” is available at http://www.confindustria.it/Aree/DocumentiPub.nsf/386B9AC5F35F1DFBC1257B6B0048B837/File/Progetto%20Confindustria%20per%20Italia.pdf.

-

5.

The projections of the effects of the policies on the real business cycle are in the “Relazione al Parlamento 2013” at http://www.mef.gov.it/doc-finanza-pubblica/rap/2013/documenti/relazione_al_Parlamento_2013.pdf.

-

6.

The agreement between Government and banks is available at http://www.mef.gov.it/certificazionecrediti/documenti/CONVENZIONE.pdf.

Appendix 2: Generalizing DID to 2 Periods and 3 Groups

The extension is straightforward, as the expected values are:

and the two treatments are mutually exclusive, so that \(D_{1}=D_{2} = 1\) is never observed. Taking the differences with respect to the control group identifies the parameters of interest \(\tau _{i,\textit{DID}}\) with \(i = \{1, 2\}.\)

We further show that using two treatment groups is informative also for the definition of \(D_1\) as treatment and \(D_{2}\) as control. Indeed, from Eq. 1 for \(D_{1}\) we get:

whereas for D2:

Considering that \(G^{D1}\) and \(G^{D2}\) are dummy variables, it follows that:

Nonetheless, in Sect. 6 we have checked all our results with also this group definition.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

D’Aurizio, L., Depalo, D. An Evaluation of the Policies on Repayment of Government’s Trade Debt in Italy. Ital Econ J 2, 167–196 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-016-0030-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-016-0030-2