Abstract

Background

Aboriginal people in British Columbia (BC), especially those residing on Indian reserves, have higher risk of unintentional fall injury than the general population. We test the hypothesis that the disparities are attributable to a combination of socioeconomic status, geographic place, and Aboriginal ethnicity.

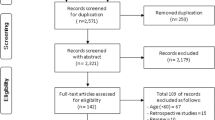

Methods

Within each of 16 Health Service Delivery Areas in BC, we identified three population groups: total population, Aboriginal off-reserve, and Aboriginal on-reserve. We calculated age and gender-standardized relative risks (SRR) of hospitalization due to unintentional fall injury (relative to the total population of BC), during time periods 1999–2003 and 2004–2008, and we obtained custom data from the 2001 and 2006 censuses (long form), describing income, education, employment, housing, proportions of urban and rural dwellers, and prevalence of Aboriginal ethnicity. We studied association of census characteristics with SRR of fall injury, by multivariable linear regression.

Results

The best-fitting model was an excellent fit (R 2 = 0.854, p < 0.001) and predicted SRRs very close to observed values for the total, Aboriginal off-reserve, and Aboriginal on-reserve populations of BC. After stepwise regression, the following terms remained: population per room, urban residence, labor force participation, income per capita, and multiplicative interactions of Aboriginal ethnicity with population per room and labor force participation.

Conclusions

The disparities are predictable by the hypothesized risk markers. Aboriginal ethnicity is not an independent risk marker: it modifies the effects of socioeconomic factors. Closing the gap in fall injury risk between the general and Aboriginal populations is likely achievable by closing the gaps in socioeconomic conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Chang VC, Do MT. Risk factors for falls among seniors: implications of gender. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;181(7):521–31. doi:10.1093/aje/kwu268.

Li W, Procter-Gray E, Lipsitz LA, Leveille SG, Hackman H, Biondolillo M, et al. Utilitarian walking, neighborhood environment, and risk of outdoor falls among older adults. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(9):e30–7. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302104.

Burrows S, Auger N, Gamache P, Hamel D. Individual and area socioeconomic inequalities in cause-specific unintentional injury mortality: 11-year follow-up study of 2.7 million Canadians. Accid Anal Prev. 2012;45:99–106. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2011.11.010.

Schiller JS, Kramarow EA, Dey AN. Fall injury episodes among noninstitutionalized older adults: United States, 2001–2003. Adv Data. 2007;392:1–16.

Balan B, Lingam L. Unintentional injuries among children in resource poor settings: where do the fingers point? Arch Dis Child. 2012;97(1):35–8. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2011-300589. Epub 2011 Sep 26.

Laflamme L, Hasselberg M, Burrows S. 20 years of research on socioeconomic inequality and children’s unintentional injuries: understanding the cause-specific evidence at hand. Int J Pediatr. 2010. 819687. doi: 10.1155/2010/819687.

Hu J, Xia Q, Jiang Y, Zhou P, Li Y. Risk factors of indoor fall injuries in community-dwelling older women: a prospective cohort study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;60(2):259–64. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2014.12.006. Epub 2014 Dec 30.

Gill T, Taylor AW, Pengelly A. A population-based survey of factors relating to the prevalence of falls in older people. Gerontology. 2005;51(5):340–5.

Chan WC, Law J, Seliske P. Bayesian spatial methods for small-area injury analysis: a study of geographical variation of falls in older people in the Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph health region of Ontario. Can Inj Prev. 2012;18(5):303–8.

Shenassa ED, Stubbendick A, Brown MJ. Social disparities in housing and related pediatric injury: a multilevel study. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(4):633–9.

West J, Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland CA, Price GM, Groom LM, Kendrick D, et al. Do rates of hospital admission for falls and hip fracture in elderly people vary by socio-economic status? Public Health. 2004;118(8):576–81.

Ramaesh R, Clement ND, Rennie L, Court-Brown C, Gaston MS. Social deprivation as a risk factor for fractures in childhood. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B(2):240–5. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.97B2.34057.

Jin A, Lalonde CE, Brussoni M, McCormick R, George MA. Injury hospitalizations due to unintentional falls among the aboriginal population of British Columbia, Canada: incidence, changes over time, and ecological analysis of risk markers, 1991–2010. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0121694. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0121694. eCollection 2015.

BC Ministry of Health [creator]. Consolidation file (MSP registration & premium billing). V2012. Population Data BC [publisher]. Data extract. MOH (2012). 2012. Available at: https://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

BC Vital Statistics Agency [creator]. Vital statistics births. Population data BC [publisher]. Data extract. BC Vital Statistics Agency. 2011. Available at: https://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

BC Vital Statistics Agency [creator]. Vital statistics deaths. Population Data BC [publisher]. Data extract. BC Vital Statistics Agency. 2011. Available at: https://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

Canadian Institute for Health Information [creator]. Discharge abstract database (Hospital Separations). Population data BC [publisher]. Data extract. MOH (2011). 2011. Available at: https://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

George MA, Jin A, Brussoni M, Lalonde CE. Is the injury gap closing between the Aboriginal and general populations of British Columbia? Health Rep. 2015;26(1):3–14.

British Columbia Vital Statistics Agency. Regional analysis of health statistics for status Indians in British Columbia, 1992–2002. Birth-related and mortality statistics for British Columbia and 16 Health Service Delivery Areas. 2004.

Brussoni M, Jin A, George MA, Lalonde CE. Aboriginal community-level predictors of injury-related hospitalizations in British Columbia, Canada. Prev Sci. 2015;16(4):560–7. doi:10.1007/s11121-014-0503-1.

Jin A, George MA, Brussoni B, Lalonde CE. Worker compensation injuries among the Aboriginal population of British Columbia, Canada: incidence, annual trends, and ecological analysis of risk markers, 1987–2010. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:710. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-710.

George MA, Jin A, Brussoni M, Lalonde CE, McCormick R. Injury risk in British Columbia, Canada, 1986 to 2009: are Aboriginal children and youth over-represented? Injur Epidemiol. 2015;2:7. doi:10.1186/s40621-015-0039-2.

Kahn HA, Sempos CT. Adjustment of data without use of multivariate models. Statistical methods in epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1989. p. 85–136.

Penney C, O’Sullivan E, Senécal S. The Community Well-Being Index (CWB): examining well-being in Inuit communities, 1981–2006. Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada. 2012. Available at: http://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100016579/1100100016580

Table 1A: Claim counts by broad group of the 1991 Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) and year; injury years 2002–2011. Available at: http://www.worksafebc.com/publications/reports/statistics_reports/occupational_injuries/2002-2011/Table1A.pdf.

Table B-1: An analysis by subsector of the 63,610 short-term disability, long-term disability, and fatal claims first paid in 2006 and an analysis of the number of days lost during 2006 on claims for all years, Work Safe BC, 2006 Statistics. Available at: http://www.worksafebc.com/publications/reports/statistics_reports/assets/pdf/stats2006.pdf.

Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Muller KE. Confounding and interaction in regression. Applied regression analysis and other multivariable methods. 2nd ed. Boston: PWS-KENT; 1988. p. 164–80.

Peters PA, Tjepkema M, Wilkins R, Fines P, Crouse DL, Chan PC, et al. Data resource profile: 1991 Canadian Census Cohort. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(5):1319–26. doi:10.1093/ije/dyt147.

Leslie WD, Lix LM, Johansson H, Oden A, McCloskey E, Kanis JA. Manitoba bone density program. independent clinical validation of a Canadian FRAX tool: fracture prediction and model calibration. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(11):2350–8. doi:10.1002/jbmr.123.

Tromp AM, Pluijm SM, Smit JH, Deeg DJ, Bouter LM, Lips P. Fall-risk screening test: a prospective study on predictors for falls in community-dwelling elderly. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(8):837–44.

Papaioannou A, Parkinson W, Cook R, Ferko N, Coker E, Adachi JD. Prediction of falls using a risk assessment tool in the acute care setting. BMC Med. 2004;2:1–10.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Institute of Aboriginal People’s Health (funding reference: AHR no. 81043). Salary support for authors was provided by the Child and Family Research Institute (AG and MB) and by the British Columbia Region, First Nations and Inuit Health Program, Health Canada (AJ). The authors thank Anna Low, Sherylyn Arabsky, and Kelly Sanderson of Population Data BC for assistance with data access and linkage and Stewart Deyell of Statistics Canada for assistance in obtaining custom tabulations of census data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This research was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Institute of Aboriginal People’s Health (funding reference: AHR no. 81043). Andrew Jin, Mariana Brussoni, M. Anne George, Christopher E. Lalonde, and Rod McCormick declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The University of British Columbia Behavioural Research Ethics Board reviewed and approved our methods (BREB file H06-80585). We studied existing provincial health care databases maintained by Population Data BC. The Data Stewards representing the British Columbia Ministry of Health and the Vital Statistics Agency of British Columbia approved our requests to access the data. This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jin, A., Brussoni, M., George, M.A. et al. Risk of Hospitalization Due to Unintentional Fall Injury in British Columbia, Canada, 1999–2008: Ecological Associations with Socioeconomic Status, Geographic Place, and Aboriginal Ethnicity. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 4, 558–570 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-016-0258-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-016-0258-4