Abstract

This article summarizes and analyzes the Children & Youth Forum and youth participation in the process during and leading up to the Third UN World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction (WCDRR) in 2015. An organizing committee consisting of international students and young professionals brought together around 200 young professionals and students from around the globe to exchange ideas and knowledge on reducing disaster risk, building resilient communities, and advocating for the inclusion of youth priorities within the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 (SFDRR). The knowledge exchange during the Forum was structured around a Toolbox for Resilience that connected to the SFDRR section on Priorities for Action. This article presents the outcomes of these young people’s participation in the disaster risk reduction capacity building events and policy-making, as well as the follow-up actions envisioned by the young participants of the Forum. The voices of the younger generation were heard in the SFDRR and young people are ready to expand their actions for the framework’s effective implementation. Young people call on technical experts, donors, NGOs, agencies, governments, and academia to partner with them on this journey to create a more resilient tomorrow together.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 (SFDRR) (UNISDR 2015) will guide the world’s efforts in the field of disaster risk reduction (DRR) into the foreseeable future. Young people possess qualities that make their active participation in DRR and response an important resource. Youth add value from local to global scales in science, policy, and practice. Through simple, honest, and persistent approaches young people apply creativity, innovation, and open-mindedness to any task that lies in their hands. Youth should be regarded as partners in conducting DRR (Fernandez and Shaw 2013; Glantz 2015).

Young people have the potential to share and contextualize knowledge on DRR, integrate local and scientific knowledge, inform protective action decision making, and advocate for change. Mitchell et al. (2008) argue that the role of children and youth has been significantly underestimated for disseminating and communicating knowledge through informal and formal risk communication networks. Positive examples of youth engagement in awareness raising and communication include: science clubs (Fernandez and Shaw 2014), youth-centered participatory videos (Haynes and Tanner 2013), school hydrometeorological programs (PRBFFWC n.d.), and hazard education programs (Finnis et al. 2010). The first campaign of the United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR) “Disaster Prevention, Education, and Youth” (UNISDR 2000) highlighted the importance of recognizing youth participation. The Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR) recognizes voluntary geospatial initiatives (for example, open street map (OSM)) as an active way to engage young people in data collection (for example, mapping buildings) to understand and manage disaster risk (GFDRR 2014). Young people have an important role to play in changing perspectives, driving positive changes in areas such as policy and accountability, and shifting mindsets from focusing on disaster response to investing in disaster preparedness (UNISDR 2000).

All stakeholders need to be involved in the decisions that affect the way they live, but there is a growing gap between national DRR policies and local-level practices (GNDR 2013). Youth were recognized as official stakeholders within the process of the SFDRR which allowed them to contribute to bridging this gap between international policy design and community implementation. Despite these positive signs, access to ways for young people to get engaged, be supported, and demonstrate their abilities remains limited. Opportunities are growing for young people to formally learn about DRR in specialized training programs, now offered in 48 countries with over 100 dedicated masters programs covering different sectors and regions (Holloway 2015). However, many young people are unaware of the opportunities that are available and need guidance on how to transfer their skills to science, policy, and practice. Meaningful intergenerational activities are needed to transfer state-of-the-art knowledge to those that will be implementing DRR initiatives in the future. This is both a short- and a long-term investment into a resilient society.

The Children & Youth Forum was established by the United Nations Major Group of Children and Youth (UNMGCY) with support from the UNISDR, in accordance with the Chair’s Summary of the Fourth Session of the Global Platform for DRR (UNISDR 2013) to highlight youth action in DRR and demonstrate the capacity of young people. The Forum allowed the Organizing Committee to mobilize young people with an interest in DRR around the world, engage them with the development of SFDRR and build their network of knowledge through meaningful peer-to-peer and intergenerational exchange, both in Sendai and beyond.

2 The Structure of Participation in the Children and Youth Forum

While the Children and Youth Forum was open to all, participants were encouraged to register in advance in order to receive arranged accommodation, with the spaces available for registered participants limited to 200. Meaningful geographic, gender, and age representation, as well as greater participation by marginalized and minority groups were all taken into account during the selection processes for both the Organizing Committee and the 190 registered participants of the Children and Youth Forum. Selection of the Organizing Committee was undertaken by Organizing Partners and Deputy Organizing Partners of the UNMGCY DRR Task Force as well as Supporting Partners of the Children & Youth Forum. Meanwhile, selection of the registered participants was performed by the registration team within the Organizing Committee with support from the Co-Chairs, Japan Secretariat and UNMGCY DRR Task Force.

Forming the quality criteria and in order to register, participants were required to answer questions relating to (1) list of organizations and networks they were an active member and the nature of their involvement; (2) what skills or resources they could bring to the Children & Youth Forum; (3) relevant DRR experience (professional, academic, or otherwise); (4) how they intended to use the knowledge and skills gained; and (5) languages spoken and relevant proficiency. In addition, participants demonstrating a background from hazard-prone regions, vulnerable communities, children affected by disasters, and other marginalized groups such as young persons living with disabilities were all prioritized to receive arranged accommodation.

The Organizing Committee, composed of students and young professionals at high-school and university level, included 28 young people from 24 countries (five from Japan), 15 females and 13 males, 30 years of age or under at the time of the World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction (WCDRR). The general principles of inclusion aimed for were not completely reflected in the actual participation because of scheduling, financial, and other constraints, given that most participants of the Children & Youth Forum were self-funded.

Most of the registered participants came from Asia (77 %), 23 % of which came from Japan. Of those participants from Asia, the largest population came from Indonesia (19 %), followed by Nepal (7 %), the Philippines (5 %), and Bangladesh, China, Malaysia, and Pakistan equally at 3 %. Participants from other regions of the world participated in smaller numbers, 9 % were from Oceania, 5 % from Europe, 4 % from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), and 2 % from North America and South America respectively.

Of the registered participants 49 % were female and 51 % were male. During the application process, participants were also able to select other gender options, but no such submissions were made.

The median age of the participants was 23. Only 2 % of the participants were under the age of 18, 3 % of the participants were over the age of 30. While definitions vary considerably, for statistical purposes, the UN defines “youth” as between 15 and 24. Under the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA), the UNMGCY is mandated to support participation of children and youth up and until the age of 30. In the context of WCDRR, participation of children was coordinated by a coalition of child-centered agencies including the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), World Vision, Plan, Save the Children, and ChildFund. Due to legal, financial and safety reasons, physical participation by many children was not possible. A series of preceding regional and global consultations were used to gather the voices of children and youth who were unable to attend WCDRR. The needs and priorities of children and youth were advocated for in all of the Preparatory Committee meeting sessions; informal Major Group consultations; Intergovernmental segment; and Multi-Stakeholder segment of the WCDRR, including a dedicated workshop as part of the official WCDRR titled “Children and Youth—Don’t Decide My Future Without Me” moderated by Ahmad Alhendawi, UN Special Envoy for Youth.

3 Methodological Approach

The following section outlines the goals the Organizing Committee of the Forum (“we”) set out to achieve, explains the way they planned to achieve these, and the means of measuring the outcomes.

3.1 What Goals Did We Want to Achieve?

3.1.1 Ensure Meaningful Participation of Young People in the Development of the SFDRR so That Their Voices are Heard

The goal was to ensure meaningful youth engagement in DRR policy design so that young people’s priorities were recognized and implemented within the SFDRR. We also wanted to build the capacity of young people to further participate in DRR policy implementation, review, and monitoring.

3.1.2 Build and Exchange Knowledge on DRR to Increase Youth Action in DRR Post-Sendai

The idea was to develop and run a Children & Youth Forum and pre-Forum as part of the WCDRR to engage, mobilize, and empower young people in DRR to exchange and further develop their knowledge, increasing their ability to play a valuable role in reducing disaster risk and building resilient communities.

3.2 How Were the Goals Achieved?

3.2.1 Ensure Meaningful Participation of Young People in DRR Policy Design

A series of regional consultations were held by UNISDR during the process leading up to the WCDRR. Young people participated in these and presented regional youth DRR priorities. The UNMGCY facilitated youth consultations prior to these regional consultations in the MENA, and the Asia–Pacific and Asia regions. Regional and global youth position papers on DRR were produced by the voluntary UNMGCY DRR Task Force in consultation, in-person, and online among members of the constituency, which were then merged with the children’s priorities from the Children in Changing Climate Coalition (CCCC) consultations and the Children’s Charter on DRR (UNICEF 2011). The final outcome was the UNMGCY Policy Brief on DRR (MGCY 2015b). UNMGCY’s DRR position paper provided the technical and strategic input for advocacy and lobbying actions during the WCDRR Preparatory Committee meetings and informal consultations/negotiations.

During the pre-WCDRR Workshops associated with the Children & Youth Forum, the policy brief was updated and a strategy for the WCDRR Intergovernmental and Multi-Stakeholder negotiations was developed by the attending young people. During the WCDRR, youth representatives applied the strategy within the Technical Working sessions and the plenary, lobbying, and bilateral meetings. UNMGCY was one of the Organizing Partners for the Working Session “Don’t Decide My Future Without Me,” that addressed the special needs of youth and children in DRR and their priorities for the post-2015 framework for DRR.

3.2.2 Build and Exchange Knowledge on DRR to Increase Youth Action in DRR

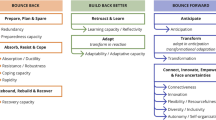

The program for the Children & Youth Forum was developed around a Toolbox for Resilience (Fig. 1). Six tools were selected as priority areas for young people to share knowledge both among peers and across generations. The tools were selected in connection with the SFDRR’s Priorities for Action (UNISDR 2015) but adjusted given the important role of youth in raising awareness and communication (Tool 5), enhancing preparedness (Tool 3), and resilient response and recovery (Tool 6) (Table 1).

The Toolbox consisted of several ways for participants to learn, share knowledge, and build capacity (Fig. 1; MGCY 2015a):

-

Pre-Forum Workshop (11–13 March 2015): Participants could select between policy and advocacy training in preparation for the WCDRR (Tool 1), study visits to disaster affected areas (Tool 2) (see Sect. 3.2, Tool 2), an understanding disaster risk workshop (Tool 2), and (social) media communication training (Tool 5).

-

Children & Youth Forum, WCDRR (13–18 March 2015): For each tool participants joined interactive breakout sessions (four options per tool) and an associated panel session moderated by young people, with a mix of student, young professional, and expert panellists (Fig. 2).

-

A Japanese-focused side event on a “Youth Disaster Prevention Declaration” developed a youth declaration among youth volunteering groups, including those from universities across Japan and multidisciplinary fields such as medicine, architecture, climate change, and risk management. Other Japanese-led events included “DRR Gaming,” organized by local high-school students, and “Drama of the Great East Japan Earthquake.”

-

In addition to the Children & Youth Forum, young people participated in the main WCDRR Intergovernmental and Multi-Stakeholder segments.

-

The knowledge gained from participating in these activities was used to formulate action plans to apply the knowledge learned in young people’s own contexts and enhance their DRR actions.

3.3 How Did We Measure the Outcomes?

3.3.1 Ensure Meaningful Participation of Young People in DRR Policy Design

The recognition of our priorities as young people, our advocacy positions, and the implementation of the proposed language in the SFDRR was a key indicator for successful youth participation in DRR policy design. It is crucial to observe the degree of participation where young people are seen as equal and important stakeholders versus non-meaningful participation (Tozier de la Poterie and Baudoin 2015). Meaningful youth participation in the design of DRR policy is guided by participation numbers, level of engagement, and the quality of outcomes produced. During the two-year period leading up to the WCDRR, young people participated in a number of forums and workshops, nationally, regionally, and globally. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, 15 collaborative youth statements were drafted. While results from these activities show a growing appreciation of DRR among the young people involved, the participation numbers are by no means representative of youth engagement in DRR. An indicator of meaningful youth participation is also the level of inclusion of marginalized and minority groups, including those from hazard-prone regions, vulnerable communities, children affected by disasters, and young persons living with disabilities as well as geographic representation, categories that often capture unheard youth voices.

How meaningful and non-meaningful participation are defined is subject to interpretation and often occurs at the level of personal feelings and behaviors. These feelings are commonly associated with a sense of lack of ownership, responsibility, or influence on a particular process. This can be correlated to Hart’s (1992) model for the “Ladder of Young People’s Participation” showing how decision making is shared at the upper end of the ladder and showing the level of nonparticipation in the form of tokenism, decoration, and manipulation at the bottom end (Hart 1992; Fig. 3). While varying degrees of participation exist in which young people are perceived to be allowed to “truly” participate (Wood and Hine 2009), consultation and collaboration are imperative requirements for genuine participation.

3.3.2 Build and Exchange Knowledge on DRR to Increase Youth Action

The findings of the Children & Youth Forum are presented by collecting the key messages young people took away from their participation in the preparatory sessions, breakout sessions, panel discussions, and the WCDRR main event. The results are outlined by Tool below (see Sect. 3.2) (as listed in the Toolbox for Resilience).

To provide an overview of the impact of the Forum, the participants were asked to fill out a feedback form 3 weeks after the event. The feedback form contained a mix of 24 open and closed questions (not including general personal details). Nine questions related to participant experience during the Forum; ten questions related to the participants’ areas of interest and intentions following the Children & Youth Forum; and five questions examined the advocacy that took place and which they would like to see for the future.

One question asked the participants to rank the usefulness of the Forum as excellent, good, average, or fair, using four indicators:

-

Networking with experts;

-

Networking with other youth;

-

Gaining knowledge; and

-

Aiding them to take action.

Participants were also asked if they were interested in being part of a community of youth involved in DRR and/or a DRR mentoring program, in order to gather information to aid the Organizing Committee of the Children & Youth Forum in planning post-Sendai action.

Open questions allowed participants to reflect on what they regarded as the highlights of the Forum, the steps they intend to take to implement the SFDRR, their current and future involvement in DRR advocacy at local, regional, and national levels, their interest in youth-based post-Sendai DRR activities, and the support needed for their DRR projects.

In total, 62 responses (N = 62) to the feedback form were collected after two weeks, representing about one-third of the participants. The results are outlined below (see Sect. 4.2).

4 Findings

The following section outlines findings showing the level of meaningful participation of young people in DRR policy design and DRR knowledge exchange for increasing actions by young people. The priorities of young people as developed during youth consultations and the level of their recognition in the SFDRR are presented. The results of the knowledge exchange in the Forum are presented per Tool in the Toolbox for Resilience.

4.1 Ensure Meaningful Participation of Young People in DRR Policy Design

Through UNMGCY, young people from around the world were mobilized and actively contributed to policy design, both online and in person, throughout the WCDRR negotiations. The outcome of these negotiations was the SFDRR, based on multi-stakeholder negotiations, regional consultations, and open-ended informal consultations that took place during the year preceding the WCDRR in Sendai.

Young people have shown dedication and provided meaningful input into the discussion on priorities and innovative solutions for DRR. Despite facing obstacles to being recognized as equal stakeholders, young people contributed throughout the process of developing the SFDRR, achieving greater recognition of young people as agents of change and working towards increased partnerships. The youth priorities within the process leading up to the WCDRR have been recognized and achieved the following outcomes:

4.1.1 Inclusion and Recognition of Children and Youth in the Decision-Making process, Implementation and Monitoring Stages of SFDRR

The unique and important role children and youth play in building a resilient society was acknowledged in the SFDRR, with the majority of youth policy positions recognized. The WCDRR Technical Working Session on Children and Youth, part of the Multi-Stakeholder Segment discussing the priorities of young people in DRR, was attended by hundreds of representatives from Member States, civil society, and agencies.

4.1.2 Support and Empower Children and Youth with the Skills and Knowledge to Strengthen Resilience in Their Communities, Recognizing Their Unique Abilities, Needs, and Priorities

The need for capacity building with youth and children was given prominence early in the negotiations, though not addressed in the discussions of the Working Group on Targets and Indicators.

4.1.3 Strengthening the Enabling Environments for Implementation, Financing, and Governance and Accountability

There has been a noticeable increase in the level of political attention given to the DRR process and the WCDRR compared with previous DRR international frameworks (UNISDR 2005). The growing participation of local community actors in resilience building efforts has called for a more people-centered framework and whole-of-society approach. Overall, governance surrounding the SFDRR has improved, however the low level of accountability could put the future implementation of the SFDRR at risk and make the framework weak and ineffective. Young people recognize the importance of ensuring accountability and financial allocation in order to ensure implementation of the SFDRR—without the needed resources we will not reach the resilient society we wish for.

4.1.4 An All-Inclusive Hazard Approach Addressing Human-Induced Disasters, Urbanization, Migration, and Their Underlying Causes

The inclusion of biological disasters was recognized, but the inclusion of conflict and fragile states remains nonexistent. Recurring small-scale and slow-onset hazards were recognized in the SFDRR, as well as language encouraging transboundary cooperation to address epidemic and displacement risks using ecosystem-based approaches.

4.1.5 Disaster Risk Assessments Must Adequately Include an Assessment of Health Impacts in Addition to Social, Economic, and Environmental Impacts

There is a tremendous increase in recognition given to the importance of social services in the SFDRR compared to the Sendai Framework Zero Draft (UNISDR 2014b) A substantial reduction in the disruption of basic services, including health and education facilities, was called for in one of seven global targets of the SFDRR. Young people are aware of how investments in disaster preparedness in the social services have a long-term impact on the resilience of communities (Aitsi-Selmi et al. 2015).

4.2 Build and Exchange Knowledge on DRR to Increase Youth Action

The Children & Youth Forum brought together around 200 young professionals and students from around the world, with different backgrounds and different levels of experience on DRR. They shared experiences of actions they were taking on-the-ground and gained knowledge to help them increase the impact of these actions. The Toolbox for Resilience grouped the results of this knowledge sharing around six thematic areas (Tools). The findings are presented by Tool (as listed in the Toolbox for Resilience).

4.2.1 Tool 1: Policy and Governance

DRR is part of sustainable development. It is important to connect the approaches and goals of international frameworks on Sustainable Development, Climate Change, and DRR (UNISDR 2014a; Kelman 2015). Young people recognize the complexities of these frameworks and the associated processes. Negotiation simulations were held during the Forum and were found to be an effective means to build the capacity of young people to engage and understand these complexities. In addition to the sessions of the Children & Youth Forum, the young people attending the WCDRR improved their skills in DRR policy and advocacy by implementing the jointly developed advocacy strategy within the SFDRR negotiations.

Frameworks should be about people and actions taken on the ground. Collaboration with all stakeholders in the environment of the problem and keeping them involved at all stages of the decision-making process is key to transforming local actions into global awareness. Young people have an important role to play in forming links between the people on-the-ground and policy and can promote inclusive and adaptive governance, especially address its challenges such as communication gaps and cultural barriers. This was particularly evident in the Japanese sessions which emphasized the important role of young people in connecting governments and citizens.

4.2.2 Tool 2: Understanding Risk

Disaster risk data and information should be available to all and young people must contribute towards making this a reality. Participatory open source mapping tools, like OSM, are recognized as powerful open platforms where young people and other stakeholders can map roads and buildings to collect exposure data at the community level to identify vulnerable areas, and the possible impacts of disasters. During the 2015 Earthquake in Nepal, young people (as part of Kathmandu Living Labs) demonstrated their capacity to utilize OSM to assist in crisis response efforts and mobilize a large number of other young people to join (Asher 2015).

In an information-rich age, there can be a surprising lack of available open data—such as spatial datasets on hazards, exposure, and vulnerability—that are necessary to conduct risk assessment. Resources for the collection, utilization, and management of data, tools, and models are also insufficient. A data revolution will happen alongside the needs and users at the national, regional, and hyper-local levels (Stuart et al. 2015). Young people are ready to be part of the open data revolution by collecting, verifying, communicating, and using open data in a fast and responsible manner.

Participants of the Children & Youth Forum had the opportunity to visit the disaster affected areas of Ishinomaki, Minami-sanriku, and Yuriage during the pre-forum workshop. Listening to the experiences of the locals as the visitors were guided through the ruins of the 2011 earthquake and tsunami gave participants greater appreciation for the risks posed by disasters. For many international participants, the concept of telling the story of a disaster by using the physical ruins as a means to enhance experiential learning and give context to the personal story being shared, was creative and new. As a young person from Kobe emphasized in the Opening Ceremony of the Children and Youth Forum, to pass on the story of the disasters experienced by a community to the inhabitants’ descendants is an important concern for Japanese people, and leaving ruins as memorials, such as the elementary school evacuation point where tragedy occurred, serves as a reminder of lessons learned, although there is still debate around the economics of doing so (IRP 2010).

4.2.3 Tool 3: Enhancing Preparedness

Technology plays an important role in disaster preparedness and response. Because young people are enormously resourceful and a powerful driving force in modern technology and innovation, their skills should be capitalized on for enhancing preparedness. InaSAFE (http://inasafe.org/en), a tool developed by the GFDRR, integrates hazard prediction and impact assessment in a decision support tool for better planning, preparedness, and response activities. The skills of young people should be utilized for developing innovative tools such as InaSAFE and methodologies that engage with all stakeholders and promote collaboration in the collection, analysis, and use of risk data and information. Aside from enhancing the use of technology, disaster preparedness programs should take into account cultural, social, and institutional aspects to ensure that programs are acceptable to local people and address their needs and real situations. Young people have the skills to create linkages between local people and modern technology.

An early warning system can only be effective if the warnings produced are received, understood, trusted, and responded to by the end users (Molinari and Handmer 2011; Cumiskey et al. 2015; Zia and Wagner 2015). Young people have an important contribution to make in creating and implementing such “people-centered” early warning systems (Basher 2006). The power of young people’s social networks should be capitalized on not only to disseminate warnings through schools, households, and communities, but also to build awareness before disasters on how to respond to warnings.

Environmental preparedness plays a very important role in DRR, which includes climate change adaptation (CCA). Human activities can reduce, cause, or accelerate the effects of disasters on our environment. Young people commit to environmentally friendly DRR actions (for example, tree planting, rooftop farming, rainwater harvesting) to build environmental preparedness. Young people should include environmental activities to address DRR, including CCA (Kelman 2015), more effectively in their current and future horizons, especially in planning and policy processes.

4.2.4 Tool 4: Investing in Resilience

Rather than financing DRR properly, there is a reliance on post-crisis financing (Lavell and Maskrey 2014). A study by the Overseas Development Institute and GFDRR estimated that only 13 % of development assistance funds for disasters between 1991 and 2010 were invested in DRR in comparison to emergency response, reconstruction, and recovery (Kellett and Caravani 2013). As a cross-cutting issue, DRR struggles to get sufficient financing, often due to the structural features of public expenditure management and state governance (Jackson 2011). A multisectoral approach is required to connect existing funding streams within development sectors and DRR financing, for example, focusing 10 % of a water and sanitation or CCA project on wider DRR. The private sector must engage in financing risk-informed decision making and complement government initiatives for risk reduction. Young people can put pressure on governments to invest in DRR, especially for investing in safe schools and hospitals. This can be in terms of structural safety (for example, complying with building codes), nonstructural safety (for example, arranging equipment in a safe or efficient manner), and operational safety (for example, regular simulations). If given the modalities to do so, young people can build community awareness and help integrate DRR into the health and educational sectors. For example, the International Federation of Medical Students’ Associations, representing 1.2 million medical students around the world, are building capacity amongst future medical professionals in disaster risk management by facilitating trainings and workshops in DRR.

Financing youth projects is challenging but the importance of investing in young people is clear (Knowles and Behrman 2003). During the WCDRR, Princess Margriet of The Netherlands stated that “The next generations are priceless for us in disasters […] investing in them and their environment equals a safer future” (Francisca, Princess Margriet 2015). Young people must be innovative about how they approach financing and partnerships; for example, requesting not only financial support but also in-kind contributions from the private sector and universities. The impact of youth projects must be measured and reported with actual evidence to stimulate further support, build trust, spread awareness, and motivate others. Young people call on donors to support youth innovations and partnerships to give them a chance to develop their ideas in a sustainable way.

4.2.5 Tool 5: Communication and Awareness

Public awareness and public education have the ability to empower all people everywhere to participate in reducing their disaster risk (IFRC 2011). Young people have an important role to play as “agents of communication” (Wisner 2006; Ronan et al. 2008) and must continue to share their DRR activities, interact with their wider communities, and be innovative with communication technology. Young people have the ability to bridge cultural and technical gaps (Mitchell et al. 2008). It is important to provide a space for young people to network with peers and across generations to facilitate this process and to ensure disaster stories and knowledge are not lost. Creating awareness of DRR and increasing communication related to DRR among young people is vital as it helps young people understand their capacity for contributing to DRR.

Young people recognize the importance of creative and innovative platforms that promote community engagement in DRR and access to information for all. Special attention needs to be paid to people in remote areas with no internet or mobile phone connections. Youth involved in DRR must continue to link to offline media to ensure no members of their communities are excluded, yet still invest in innovative technologies and utilize those that are locally applicable. Mobile applications—for example, the Messiah Emergency Alert Messenger (Messiah n.d.) developed by young Pakistanis, and social media like Facebook’s I’m Safe notification tool—offer effective means for improving communication in a disaster and saving lives. Young people have a huge role to play in developing and using such technology.

Gaming is an effective way to engage children, young people, and adults with DRR issues like early warning systems, forecasting, and disaster preparation in a fun, proactive, and interactive way. Games can be used to help people experience the complexity of future risks (Mendler de Suarez et al. 2012). Games need to be simple and clear so the key messages are understood and are passed along through peer-peer training. Numerous paper-based and digital games are freely available online, for example, “Ready,” and “Paying for Predictions” from the Red Cross/Red Crescent Climate Centre (RCCC n.d.) and the “Stop Disasters” online game from the UNISDR (UNISDR and Playerthree 2007).

Ronan et al. (2001) found a good strategy to help children and youth to understand risks is to encourage them to talk with parents about disasters. Sharing powerful stories has the ability to shift mindsets and facilitate disaster recovery as stories can be told to people from all backgrounds in a way that is relatable and understandable. Effective storytelling shares experiences in a personal way, is short and simple, ends on a positive note, and can vary in the means of delivery, for example, through action and drama or arts and crafts. Young people who engage in storytelling have the means to inspire others and to further motivate themselves. Storytelling enables the passing on of disaster experiences and knowledge from older to younger generations.

4.2.6 Tool 6: Resilient Response and Recovery

The response and recovery process in a disaster is a complex, disheartening, and challenging journey for communities. Continued educational and psychosocial resources are needed during and after the event, which can be difficult (IFRC 2011). Even small emergencies should be taken seriously and learned from to prepare for the next. Community volunteers often mobilize to save lives, reduce economic losses, and diminish the impacts of disaster. Young people see the importance of taking care of our communities and building a culture of safety and security during and after disasters. They can provide interesting and practical ideas for rebuilding communities (Bartlett 2008). Hearts, minds, and souls are affected by disasters and volunteers need the skills to address these impacts. Psychological first aid using sports, theater, drama, and art offers an innovative means to engage the community.

The capacity of volunteer groups and services can be greatly increased by opening up opportunities to willing young members of the community and providing them with the required skills to match their abilities and capabilities. Young people have an important role in responding to disasters as intergenerational agents, and also in making sure they themselves, their families and communities, as well as their organizations are prepared. Inspiring new volunteers, retaining existing volunteers, and sustaining a strong volunteer network are challenging. Young volunteers should be valued and rewarded for their efforts as part of the experience by making it fun and interactive.

The Toolbox for Resilience was found to be a useful means to structure the content of the Forum and create a link to the SFDRR Priorities for Action. The toolbox emphasized communication and awareness and split the fourth Priority for Action into two areas, one on preparedness and one on response and recovery. This approach was found to be useful because of the role of young people in communicating risk, building awareness, setting the path for effective preparedness, and acting as volunteers in disaster response and recovery. These adaptations were found to reflect the interests of young people and the content of the Forum, centered around the Toolbox for Resilience, offered participants a diverse, yet structured approach to learning about DRR. The importance of giving attention to Communication and Awareness (Tool 5) was evident, but this issue does not have a dedicated focus in the SFDRR’s Priorities for Action. The material developed for the toolbox will be packaged and made available to the participants. The best means to do this has not yet been decided. It is anticipated that the Toolbox can be used to form a knowledge platform for young people to share DRR knowledge. This can then be built upon by young experts in the science and policy arenas and feed into project implementation. However, the toolbox requires additional work to further detail subcategories for the tools. A more explicit means to identify overarching issues, including the urban landscape, health and education, and the environment would be beneficial.

5 Outcomes

This section presents the outcomes of the Forum and the next steps for moving forward relating to DRR policy design and knowledge exchange during the Forum. The results of a feedback survey of Forum participants are presented along with initial ideas for continuing the engagement of young people in DRR.

5.1 Concrete Steps in Moving DRR Policy Design Forward

The next step in international DRR policy development facilitated by the UNISDR is to create a Means of Implementation (MoI) to guide the implementation of the SFDRR, as well as develop indicators to assist in the monitoring. The process of creating this, as provided by the UNISDR and the Co-chairs for the WCDRR, is not transparent and inclusive, and so far the UNMGCY has not been asked to be part of the process. We hope that young people will be let back into the discussion. The MoI and the indicators will have the biggest impact on DRR practice, research, and policy at the local and national levels and it is important to include young people’s voices in their development.

It is important to remember that the SFDRR is only one milestone in the post-2015 development agenda. There are three other larger processes still in progress that relate to additional new international frameworks: the Finance for Development Framework, the Sustainable Development Goals, and the new Climate Change Framework (UNISDR 2014a). To reach the disaster-resilient world we aim for, it is crucial to recognize DRR in these frameworks as well. UNMGCY will continue to take action to ensure that DRR policies developed by young people are heard and implemented in the outcome documents of these processes.

5.2 Build and Exchange DRR Knowledge to Increase Action

The Children & Youth Forum received very positive feedback from the participants. The majority of participants indicated that the Forum gave them either excellent or good opportunities to network with other young people (89 %) and experts (77 %), to build knowledge (87 %), and to facilitate actions (89 %) (Fig. 4). This feedback is based on the questionnaires completed by participants (N = 62) and is comparable to the positive informal feedback the Forum organizers received from participants after the Forum.

There is great demand for additional support of continued mentoring and knowledge-sharing. The majority of participants (86 %) indicated they would like to participate in a topic-specific mentoring program (Fig. 5). Key topics of interest directly link back to the topics covered in the Toolbox for Resilience, including communication and awareness raising; community mapping; early warning systems; psychosocial aspects of disaster recovery; environmental impacts on disaster risk; volunteering in disaster response; and entrepreneurship Furthermore, 95 % indicated that they would like to be part of a DRR community to continue exchanging knowledge and networks. These results will help to directly inform post-Sendai actions of the Children & Youth Forum organizers.

The feedback from the participants stressed the importance of working towards solutions collaboratively with partners to build and exchange our knowledge on DRR to devise solutions, with one participant from Indonesia noting “The forum gave me a new point of view on DRR—making a resilient world is not an easy job—we really have to work hard “together” and never underestimate any kind of background or job.”

It is clear from the results that the participants are ready to use the knowledge and connections they gained from participating in policy negotiations and the Forum to expand their actions on DRR in their local contexts. Attending the Forum and participating in the policy design has motivated them to go back and implement the SFDRR at a local level. Participants of the Children & Youth Forum voiced their plans, with one participant from Libya saying “I am planning to start a huge project to determine the needs and to develop our plans on DRR with youth organizations.”

The majority of participants (80 %) indicated that they have contacts with local, national, or regional authorities responsible for DRR in their own contexts. They are committed to utilizing these existing connections and to creating long-term youth partnerships with local NGOs, universities, schools, media, and government authorities, acting as “agents of change” in their own contexts. These actions have great potential to connect local action with global policy. As a participant from the Philippines commented, “The youth, with our dynamism and ideal minds, should now engage with dialogues among fellow youth from all over the world, and among inspiring elders who can lead us to implement and fine-tune our imperfect visions and action plans.”

6 Discussion

6.1 Level of Inclusive Youth Engagement in Policy Design

The frequent disconnect between policy and practice remains an ongoing challenge for a majority of stakeholders, including young people. The benefits of enhancing the interconnection between policy priorities and practical experiences among young people were recognized during the Children and Youth Forum and WCDRR process. Future youth-led efforts will aim to improve collaboration and knowledge exchange.

6.2 Youth Participation in the Forum

Overall there was a good representation of global youth, though a large number of the participants were from southeast Asia. Reasons for this include the strength of youth DRR networks in this area, particularly those facilitated by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, and the provision of funding support from home universities and institutions in this area to attend the Forum. Visa issues prevented many young people from Asia and Africa from attending. Attendance by post-graduate students completing their Ph.D. and Masters level studies in DRR was poor and limited to young working professionals, although many demonstrated strong backgrounds from fields indirectly linked to DRR, for example health and engineering. Representation of young people coming from the European Union, North America, and the Pacific was low, and there was a lack of participation from South America, with youth from this region experiencing significant difficulties in attending. Potential explanations are that more experienced young practitioners no longer personally identify or associate themselves with the “Children and Youth” arena or that they may be too busy to do so. Further outreach to universities, especially those with dedicated disaster-related courses, is necessary and further exploration of funding opportunities is needed to ensure representation from these countries. Reflecting on the journey ahead, it is important that we target young people in their individual capacity, that is, as researchers, practitioners, volunteers, students, and not just based on their participation in youth organizations.

6.3 Knowledge Exchange in the Forum

The findings showed that participants found the Forum either excellent or good in terms of knowledge exchange and networking. This finding was expected as observations in the Forum itself showed that participants were actively engaged in the breakout sessions and panel discussions. Participants had space to share their experiences, learn from others working in the same field, and gain knowledge on completely new topics. The interactive and participatory sessions linked to the Toolbox received a lot of positive feedback, such as those using role play, mapping, and games. Participants indicated that these allowed them to learn in new ways and take this knowledge home into their own contexts. As an Indonesian participant explains in the feedback form “the game session […] really inspired me and makes me want to share all that I have got to the other people in my society. I also would like to make a game with disasters-themed for Indonesian children.” The success of the sessions was aided by the mix of young people and expert facilitators. The support from experts in DRR science, policy, and practice was outstanding and vital to the success of this intergenerational exchange. Aside from these positive notes, it was recognized by the Forum organizers that there were a large number of sessions to choose from, especially when the main WCDRR events were taking place in parallel. It is recommended that future programs continue to offer as many interactive sessions as possible, but aim to hold youth sessions on separate days from the main events so participants can actively participate in both.

6.4 Post-Sendai Action

The SFDRR has been adopted, but the need remains to agree on the indicators and the MoI. Young people aim to continue their involvement in the processes regardless of whether or not they are officially included to show best practice in the form of process coherence, and to ensure that DRR is included in the post-2015 development agenda. The SFDRR needs further translation into understandable means for local-level interpretation and the authors will support any efforts in this regard. We plan to continue outreach to young people in DRR through available networks and continue to develop a young DRR knowledge community, including a mentoring program. This will enhance exchange among participants and improve communication between those involved in policy and those involved in practice. Challenges lie ahead for us to sustainably implement such actions without sufficient financial and human resources, but we are ready to work to the best of our abilities.

7 Conclusion

The WCDRR was not the end but the beginning of enhanced actions on DRR. The Children & Youth Forum succeeded in bringing around 200 young people from around the world to Sendai to witness the adoption of the SFDRR, exchange knowledge, develop new knowledge (Weichselgartner and Pigeon 2015), and find like-minded young people and experts to partner with on their journey to resilience. Participants left Sendai with a clear understanding of the important role they can play in building resilience in their communities. It is now in their hands to empower, motivate, and share the knowledge obtained through the process with other young people around the world. Participants gained knowledge, shared experiences, and networked with fellow youth and experts. Upon leaving Sendai, there was a consensus among Forum organizers, participants, and supporters that this interaction needed to continue in some shape or form. The findings highlighted the demand for mentoring programs to support young people and the need for continued knowledge exchange post-Sendai among young people and experts. The Children & Youth Forum organizers commit to developing such post-Sendai youth actions to the best of their abilities.

A number of stakeholders in the WCDRR have recognized the benefits of building the capacity of future generations and included young people in their voluntary commitments. This will result in increased investments in enhancing the capacity of the coming generation to take action on DRR. Youth-led organizations have already taken a lead in promoting self-accountability and expressed their commitments in alignment with UNISDR’s call for voluntary commitments and as an officially recognized outcome of the WCDRR. Young people are now ready to expand their actions as leaders and partners, in connecting science, policy, and practice, in supporting effective accountability measures, and to implement the SFDRR. We call on partners to let us embark on this journey together, and support each other along the way.

References

Aitsi-Selmi, A., S. Egawa, H. Sasaki, C. Wannous, and V. Murray. 2015. The Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction: Renewing the global commitment to people’s resilience, health, and well-being. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 6(2). doi:10.1007/s13753-015-0050-9.

Arnstein, S.R. 1969. A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35(4): 216–224.

Asher, S. 2015. How “crisis mapping” is helping relief efforts in Nepal. BBC News. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-32603870?ocid=socialflow_facebook. Accessed 10 May 2015.

Bartlett, S. 2008. After the tsunami in Cooks Nagar: The challenges of participatory rebuilding. Children Youth and Environments 18(1): 470–484.

Basher, R. 2006. Global early warning systems for natural hazards: Systematic and people-centred. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 364(1845): 2167–2182.

Cumiskey, L., M. Werner, K. Meijer, S.H.M. Fakhruddin, and A. Hassan. 2015. Improving the social performance of flash flood early warnings using mobile services. International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment 6(1): 57–72.

Fernandez, G., and R. Shaw. 2013. Youth Council participation in disaster risk reduction in Infanta and Makati, Philippines: A policy review. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 4(3): 126–136.

Fernandez, G., and R. Shaw. 2014. Participation of Youth Councils in local-level HFA implementation in Infanta and Makati, Philippines and its policy implications. Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy 5(3): 259–278.

Finnis, K.K., D.M. Johnston, K.R. Ronan, and J.D. White. 2010. Hazard perceptions and preparedness of Taranaki youth. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal 19(2): 175–184.

Francisca, Princess Margriet. 2015. Speech made at Working Session Commitments to Safe Schools, 14 March 2015, Third UN World Conference on DRR, Sendai, Japan.

GFDRR (Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery). 2014. Understanding risk. The evolution of disaster risk management. Washington, DC. https://www.gfdrr.org/sites/gfdrr.org/files/publication/_Understanding_Risk-Web_Version-rev_1.7.3.pdf. Accessed 23 April 2015.

Glantz, M.H. 2015. The Antalya statement—An expert forum on disaster risk reduction (DRR) in a changing climate: Lessons learned about lessons learned. Convened by USAID, CCB/CU, WMO and TSMS with the support of NOAA and GFDRR. Antalya, Turkey.

GNDR (Global Network of Civil Society Organizations for Disaster Reduction). 2013. Views from the frontline. http://www.globalnetwork-dr.org/views-from-the-frontline/vfl-2013.html. Accessed 15 Feb 2015.

Hart, R.A. 1992. Children’s participation: From tokenism to citizenship. No. inness92/6. UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre.

Haynes, K., and T.M. Tanner. 2013. Empowering young people and strengthening resilience: Youth-centred participatory video as a tool for climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction. Children’s Geographies 13(3): 357–371.

Holloway, A. 2015. Strategic mobilisation of higher education institutions in disaster risk reduction capacity building: Experience of Periperi U. Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction 2015. Research Alliance for Disaster and Risk Reduction (RADAR), Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa.

IFRC (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies). 2011. Public awareness and public education for disaster risk reduction: A guide. https://www.ifrc.org/Global/Publications/disasters/reducing_risks/302200-Public-awareness-DDR-guide-EN.pdf. Accessed 1 May 2015.

IRP (International Recovery Platform). 2010. Guidance note on recovery: Telling live lessons. http://www.recoveryplatform.org/assets/Guidance_Notes/Telling%20Live%20Lessons%204.20.2010%20%281%29.pdf. Accessed 15 May 2015.

Jackson, D. 2011. Effective financial mechanisms at the national and local level for disaster risk reduction. Mid-term review of UNISDR Hyogo Framework for Action. United Nations Capital Development Fund, UNCDF.

Kellett, J., and A. Caravani. 2013. Financing disaster risk reduction: A 20 year story of international aid. Overseas Development Institute. http://www.odi.org.uk/publications/7452-climate-finance-disaster-risk-reduction. Accessed 15 May 2015.

Kelman, I. 2015. Climate change and the Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 6(2). doi:10.1007/s13753-015-0046-5.

Knowles, J.C., and J.R. Behrman. 2003. Assessing the economic returns to investing in youth in developing countries. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Lavell, A., and A. Maskrey. 2014. The future of disaster risk management. Environmental Hazards 13(4): 267–280.

Mendler de Suarez, J., P. Suarez, C. Bachofen, N. Fortugno, J. Goentzel, P. Gonçalves, N. Grist, C. Macklin, et al. 2012. Games for a new climate: Experiencing the complexity of future risks. Pardee Center Task Force Report. Boston: The Frederick S. Pardee Center for the Study of the Longer-Range Future.

Messiah. n.d. Messiah App. http://www.messiahapp.com/. Accessed 15 April 2015.

MGCY (Major Group for Children & Youth). 2015a. Children & Youth Forum Programme. Third UN World Conference on DRR. http://youthbeyonddisasters.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Children-Youth-Forum-FINAL-Full-Program-Mar-12.pdf. Accessed 29 Mar 2015.

MGCY (Major Group for Children & Youth). 2015b. Policy brief on disaster risk reduction. Second Session of the Preparatory Committee Meeting. https://childrenyouth.files.wordpress.com/2014/12/2nd-prepcom-for-wcdrr-mgcy-policy-brief.pdf. Accessed 27 April 2015.

Mitchell, T., K. Haynes, N. Hall, W. Choong, and K. Oven. 2008. The roles of children and youth in communicating disaster risk. Children Youth and Environments 18(1): 254–279.

Molinari, D., and J. Handmer. 2011. A behavioural model for quantifying flood warning effectiveness. Journal of Flood Risk Management 4(1): 23–32.

PRBFFWC (Pampanga River Basin Flood Forecasting & Warning Center). n.d. Bulacan SHINE Program. http://bulacanshine.webs.com/shineprogram.htm. Accessed 15 Feb 2015.

RCCC (Red Cross/Red Crescent Climate Centre). n.d. Games overview. http://www.climatecentre.org/resources-games/games-overview. Accessed 1 April 2015.

Ronan, K.R., K. Crellin, D.M. Johnston, K. Finnis, D. Paton, and J. Becker. 2008. Promoting child and family resilience to disasters: Effects, interventions, and prevention effectiveness. Children Youth and Environments 18(1): 332–353.

Ronan, K.R., D. Johnston, and T. Wairekei. 2001. Hazards education in schools: Current findings, future directions. In APEC workshop on dissemination of disaster mitigation technologies for humanistic concerns phase, vol. 1: 18–21.

Stuart, E., E. Samman, W. Avis, and T. Berline.2015. The data revolution finding the missing millions. Overseas Development Institute. http://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/9604.pdf. Accessed 10 May 2015.

Tozier de la Poterie, A., and M.-A. Baudoin. 2015. From Yokohama to Sendai: Approaches to participation in international disaster risk reduction frameworks. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 6(2). doi:10.1007/s13753-015-0053-6.

UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund). 2011. Children’s charter for disaster risk reduction. http://www.unicef.org/mozambique/children_charter-May2011.pdf. Accessed 30 May 2015.

UNISDR (United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction). 2000. United Nations 2000 World Disaster Reduction Campaign to focus on disaster prevention, education and youth. http://www.unisdr.org/2000/campaign/pa-camp00-kit-eng.htm. Accessed 23 April 2015.

UNISDR (United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction). 2005. Hyogo framework for action 2005–2015: Building the resilience of nations and communities to disasters. http://www.unisdr.org/2005/wcdr/intergover/official-doc/L-docs/Hyogoframework-for-action-english.pdf. Accessed 14 Feb 2015.

UNISDR (United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction). 2013. Chair’s summary fourth session of the global platform for disaster risk reduction. http://www.preventionweb.net/files/33306_finalchairssummaryoffourthsessionof.pdf. Accessed 30 May 2015.

UNISDR (United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction). 2014a. Coherence and mutual reinforcement between a post-2015 framework for disaster risk reduction. Sustainable Development Goals and the Conference of Parties to the UNFCCC. http://www.preventionweb.net/documents/posthfa/Mutual_reinforcement_of_2015_Agendas_UNISDR.pdf. Accessed 9 April 2015.

UNISDR (United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction). 2014b. Post-2015 framework for disaster risk reduction. Zero draft submitted by the co-Chairs of the Preparatory Committee. http://www.wcdrr.org/uploads/1419081E.pdf. Accessed 11 April 2015.

UNISDR (United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction). 2015. Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction 2015–2030. http://www.wcdrr.org/uploads/Sendai_Framework_for_Disaster_Risk_Reduction_2015–2030.pdf. Accessed 23 Mar 2015.

UNISDR (United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction) and Playerthree. 2007. Stop disasters! A disaster simulation game from the UN/ISDR. http://www.stopdisastersgame.org/en/home.html. Accessed 1 April 2015.

Weichselgartner, J., and P. Pigeon. 2015. The role of knowledge in disaster risk reduction. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 6(2). doi:10.1007/s13753-015-0052-7.

Wisner, B. 2006. Let our children teach us! A review of the role of education and knowledge in disaster risk reduction. ISDR Thematic Cluster/Platform on Knowledge and Education. Bangalore: Books for Change. http://www.unisdr.org/2005/task-force/working%20groups/knowledge-education/docs/Let-our-Children-Teach-Us.pdf. Accessed 1 April 2015.

Wood, J., and J. Hine. 2009. Work with young people: Theory and policy for practice. London: Sage.

Zia, A., and C.H. Wagner. 2015. Mainstreaming early warning systems in development and planning processes: Multilevel implementation of Sendai framework in Indus and Sahel. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 6(2). doi:10.1007/s13753-015-0048-3.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Children & Youth Forum organizers and the Organizing Committee, Japan Secretariat, speakers, facilitators, and all the young participants of the WCDRR for their dedicated contributions. The UNMGCY are acknowledged for their commitment to ensure meaningful participation of young people in the SFDRR 2015–2030 and for organizing the Children & Youth Forum. Further thanks to our partners and sponsors for financially supporting the Forum and offering their valuable time and advice, especially UNISDR. The authors would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their feedback on this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Cumiskey, L., Hoang, T., Suzuki, S. et al. Youth Participation at the Third UN World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction. Int J Disaster Risk Sci 6, 150–163 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-015-0054-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-015-0054-5