Abstract

A study of 612 CPAs employed in four separate regions of the People’s Republic of China shows that they exhibit ethical orientations that are not significantly different from one another and that they do not, as a group identify with the Subjectivist description provided in the Forsyth et al. (Journal of Business Ethics 8(83):813–833, 2008) meta-analytic international study involving the Ethical Position Questionnaire. Confirmatory factor analysis did however establish the validity of the instrument as a measure of idealistic and relativistic tendencies. It was established that the ethical tone within local accounting firms plays a significant role in forming ethical positions and that these variables together work to influence ethical judgement making with respect to issues involving independence and objectivity. The constructs of relativism and idealism act as reliable predictors of moral choice, but need to be carefully interpreted in the context of field research. The study highlights concerns about the ethicality of a fledgling group of professionals having to cope with the exigencies associated with the world’s fastest developing economy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

China’s economic growth over the past decade has been outstanding and relatively unaffected by the financial crises that have troubled developed nations in recent times. Business Management International (BMI) rates China highly in most areas. It reports that China’s economic policymakers have proved capable, and are likely to continue their methodical and professional approach to reforming the economy. Despite these results, BMI remains concerned about China’s future, rating it low in terms of its risks to realisation of returns rating (BMI China Commercial Banking Report 2010).

According to BMI, a major underlying issue threatening China’s social and economic future is the growth of corruption. The close relations between provincial leaders and local businesses are fostering corruption and are making it harder for the central government to enforce its economic reform policies. As a consequence, Chinese corporate governance is weak and non-transparent by western standards. China’s road to success is littered with reports of business scandals, many involving government officials at the provincial and central level.

Snell and Tseng (2002) comment that China faces major challenges to its moral integrity in business due to a weak legal system, limited civic accountability, market distortion, public cynicism and a self-interested workforce. Numerous scandals have been reported in recent times, including government representatives as major contributors. These include a report by the National Audit Office identifying numerous incidents of fabricated disclosures, involving fraudulent accounting practices and over-inflating profits by more than 80% of the accounting firms subject to examination. (Tai 2003) In 1998, a public accounting practice review conducted by the Ministry of Finance identified widespread unethical practices in such firms. As a result of that review, 344 CPA firms and 1,441 branch offices of firms were closed down, 352 CPAs lost their licences to practise, and many more were issued warnings for ethical breaches. (Tang 1999) Furthermore, the China Securities Regulatory Commission regularly issues reprimands to listed companies for various forms of infringement (Shi and Weisert 2002).

The issue that interests the authors of this study and which has been largely left unaddressed to date concerns the ethicality of the individual members of the Chinese Institute of Certified Public Accountants (CICPA). Traditional Confucian principles previously embraced by the populace are bowing to the growing influence of western-based systems which their profession espouses and the government’s strident call for its people to develop a work ethic that maximises both personal and national wealth. Given the apprehension expressed by BMI and other China observers about the nation’s goal to develop at any cost, its lack of effective legal and social infrastructures, and the high incidence of fraud and corruption in business, it would be valuable to understand how auditors’ ethical orientations act to influence decision making in the context of their workplace environment.

Literature review

China accounting profession and code of conduct

There was no Code of Professional Conduct governing the moral expectations of auditors during the early 1980s, and their attitudes towards the Party and its laws had altered little as most were retired government officers who had been educated within the previous Soviet-based system of accounting. This changed after the formation of the CICPA in 1988.

The CICPA exercises the management and service functions by virtue of the powers vested by the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Certified Public Accountants, the Charter of the Chinese Institute of Certified Public Accountants, and the relevant laws and regulations. Its mission includes providing services to its members, monitoring the service quality and professional ethics of members, regulating the CPA profession according to relevant laws, and coordinating the relationship within and beyond the CPA profession. (Chinese Institute of Certified Public Accountants 2007) The Chinese Code of Professional Conduct titled General Standards on Professional Ethics (GSPE) was issued by the CICPA in accordance with the Law in 1993 and was revised in 1996.

The Code is succinct but explicit, and its articles require all CPAs to observe the principles of independence, objectivity and fair dealing in performing professional activities and to maintain independence in fact and in appearance. Professional judgements must not be influenced by others or by any circumstances and personal feelings, and they should avoid any activities which could impair audit independence. The moral content of these articles underpins its objective to provide reliable and trustworthy services for the benefit of the profession’s stakeholders. As an independent national representative body with international affiliations, the CICPA has as its guiding principle, a desire to attain professional credibility and integrity. By 2006, it had more than 5,600 group members (accounting firms) and over a 140,000 individual members of which half were actively employed in the industry. (Chinese Institute of Certified Public Accountants 2007)

Ethical orientations

Barnett et al. (1994) study of normative research concluded that…“few individuals are strict teleogists or deontologists” (p. 471). They also conclude that individuals often find it hard to consciously apply normative perspectives when dealing with ethical dilemmas in business situations. Individual cognitive responses to issues depend on levels of sensitivity and reasoning ability (Kohlberg 1981; Rest 1986), which in themselves form a basis for various heuristics enabling them to form patterns or orientations of thought that are applied in various situations.

Schlenker and Forsyth (1977) suggest that individuals vary in their outlook, adopting strategies to deal with ethical issues that encompass two independent orientations, namely idealism and relativism. Idealistic perspectives involve the maintenance of universal moral rules, with an emphasis on the welfare of others, while relativism focuses more on the circumstances, which can accommodate a self interest component. Using these moral premises, Forsyth (1980) developed a 20-item Ethics Position Questionnaire (EPQ) to assess individual ethical orientations along relativist and idealist dimensions. A listing of the two sets of ten questions measuring idealism and relativism is provided in Appendix 1.

The first set of ten questions presents extreme idealist positions providing respondents with an opportunity to moderate their perspectives along a nine-point Likert scale. Idealism in its extreme form presents the moral imperative that any behaviour that disadvantages one or more parties is unacceptable. Untenable in most everyday situations, a respondent is expected to indicate a less intense position that permits them to apply some form of speculative formulation or heuristic.

Relativistic orientations are measured using an additional ten questions and include meta-ethical statements suggesting that many fundamental moral disagreements cannot be rationally resolved, and on this basis, moral judgements embodied in laws and traditions lack moral authority or normative force (Swoler 2003). Forsyth (1980) contends that within the framework of the test instrument, relativism measures the degree to which individuals reject universal moral norms in making ethical judgements. Relativism has been interpreted in a number of ways and has its share of critics (Velasquez 2006); however, the concepts can be seen to support situational ethics as well as heuristics that entertain Machiavellian proclivities (Zhao 2008).

Relativism is not described as the polar opposite of idealism, but a separate dimension (Al-Khatib et al. 2007; Shaub et al. 1993). Forsyth (1980) posits that the two models explaining ethical orientation can be placed in an orthogonal 2 × 2-dimensional array, depending on the extent to which an individual rejects universal moral rules in favour of relativism, or the degree to which he or she avoids harm to others. The four orientations are Situationist, Absolutist, Subjectivist, and Exceptionist. According to Forsyth, Situationists and Subjectivists are high on the relativism dimension. They reject moral rules and make decisions based on given situations or personal feelings. Situationists are classified as utilitarians, whereas Subjectivists are classified as ethical egoists. Absolutists and Exceptionists on the other hand are low on relativism; their actions follow moral rules regardless of situations and personal feelings. Absolutists doggedly apply categorical imperatives, while Exceptionists are classified as rule-utilitarians.

Application of the EPQ

Many researchers have applied the EPQ in different cross-sectional and comparative contexts involving respondents from a variety of business situations. Recently, Forsyth et al. (2008) completed a meta-analytic investigation of 139 sample surveys that applied the instrument in 29 different countries including 30,230 respondents. The objective of the research was to determine cultural differences in relativism and idealism using the four-typology approach referred to above in the classification process. Progress was somewhat affected by the very different approaches the studies applied to collecting and measuring data, and some of these issues will be addressed later in this study. However, Forsyth et al. (2008) were able to draw interesting and relevant conclusions, including associations with Hofstede’s culture-based model (Hofstede 1980).

Relevant scores for average idealism and relativism were standardised for each of the surveys and national groups mapped within the 2 × 2 matrix. The point of intersection between the two axes was based on the overall median value for each of the orientations. Forsyth et al. (2008) included five China surveys involving 1,081 respondents. As a group, these respondents were classified as Subjectivists, identifying very strongly with the relativistic statements (among the top five nations), but scoring somewhat less than the median score for idealism. Interestingly, Hong Kong and Japan were classified as occupying the same least populated quadrant as China. The majority of national sample studies rated above the median score for idealism.

A number of research studies have accepted Forsyth’s explanation of the four ideological types and applied the EPQ to explore various interest groups, including mainly business students and career professionals, to determine whether membership of one of the four types (Absolutist, Situationist, Subjectivist, and Exceptionist) can be used to explain differences in the way individuals view various ethical issues (e.g. Barnett et al. 1994, 1998; Tansey et al. 1994; Bass et al. 1998; Hartikainen and Torstila 2004; and Marques and Azevedo-Pereira 2009). Survey issues generally include an evaluation of ethical statements, questionable practice vignettes or lengthy scenarios. The dependent variable may consist of individual scores or an average of a number of responses. Observed differences in group membership are generally explained in terms of the extent to which respondents apply either idealistic or relativistic tendencies.

Most non-Chinese studies use variously constructed dimensions for idealism and relativism to assess whether relationships with judgement making can be identified (e.g. Shaub et al. 1993; Barnett et al. 1994, 1996, 1998; Douglas and Schwartz 1999; Singhapakdi et al. 2000; Chui and Stembridge 2001; Davies et al. 2001; and Douglas et al. 2001). The findings are generally unanimous in their observation that respondents taking an idealistic position rate unethical activities more conservatively than their relativistic counterparts. Idealists identify more with a need to adhere to principles (generally codified in some form) which support decisions that avoid harm and maximise the welfare of society. Relativists on the other hand question the validity of societal rules and regulations and maintain a situational perspective. Although the ten statements making up the relativism scale are couched in objective third person terms, it is clear that they provide respondents with an opportunity to take a view that permits a degree of self interest, and this affects their judgement making. Positive associations between Machiavellianism and relativism have been explored in both a western (Wakefield 2008) and Chinese (Zhao 2008) context and demonstrate that individuals identifying closely with both belief systems are less likely to reject questionable activities compared to their idealistic counterparts.

China-based studies using the Ethics Position Questionnaire

Past researchers have tended to identify Chinese subjects as demonstrating relativistic tendencies (Dolecheck and Dolecheck 1987; Hampden-Turner and Trompenaars 1993; Ralston et al. 1995; Jackson et al. 2000) or less idealistic than their western counterparts (Whitcomb et al. 1998), citing self-interest and profit seeking as motivating factors. A literature search provides a limited number of recent papers referring to the study of ethical orientations of Chinese business personnel utilising the EPQ. Some involve a comparative analysis with other nations, while others study orientations within a regional context. The former devote attention to explaining variations in ethical positions based on cultural issues underpinning belief systems and discuss differences that focus on Hofstede’s (1980) cultural constructs of power distance, collectivism, femininity and uncertainty avoidance.

Douglas and Weir (2005) found no difference in idealist positions between Chinese and American managers. However, their results showed that Chinese managers (including 142 respondents employed in Beijing and Hong Kong) were significantly higher on the high idealism sub-categories: Situationists (high relativism, high idealism) and Absolutists (low relativism, high idealism). With respect to differences in judgement making, they hypothesised that models of slack creation in budgeting behaviour vary across different national cultural settings. They discerned that for US managers, slack creation behaviour increases as incentive increases and decreases as idealism increases, while for Chinese managers, only incentive (not idealism or relativism) appeared to affect behaviour.

A recent comparative study completed by Robertson et al. (2008) examined differences in ethical orientations between a combined sample of 128 business employees from major urban areas in both China and Peru. Using the standard EPQ measures, the researchers found that Chinese employees were more relativistic and less idealistic than their Peruvian counterparts. They also discovered that these differences contributed significantly to the finding that Chinese respondents were more likely to sacrifice ethical standards when financial gain is possible. They surmised that this finding was likely attributable to the high relativism score, which they also believed could be explained by cultural differences, the Chinese identifying more with collectivist principles and the attendant negative aspects of guanxi.

Redfern and Crawford (2004) and Redfern (2005) reported the results of a regional study that examined the ethical orientations of two groupings of managers. The former included a sample of 115 managers from southern and northern regions of China, and the second concerned 206 managers organised according to whether they were employed in high or low regions of industrialisation. In the first paper, the authors reported significant differences in ethical ideology between southern and northern managers, the former scoring significantly higher on idealism, “suggestive of the higher levels of exposure to Western lifestyle practices and ideology enjoyed by coastal regions in the southeast of China, in contrast to the more dogmatic and bureaucratic history of the country’s capital, Beijing” (Redfern and Crawford 2004, 207). In her second exploratory study, Redfern (2005) described managers as Situationists based on the finding that they scored higher than the nine-point mid-scale scores for both idealism and relativism. She also reported that managers in the more industrialised regions scored higher in both constructs compared to their counterparts in the less industrialised areas and suggested that this might be an indication of the existence of more humanitarian approaches to issues involving business ethics as a result of western influences and practices. At the same time, she suggested that modernistic styles associated with industrialization may encourage relativistic tendencies.

Al-Khatib et al. (2007) examined the ethical orientations of 300 Chinese managers from Tianjin (north east China) as part of a wider study, which included Machiavellian tendencies and their connection with negotiation processes in business. Standard measures for relativism and idealism were included in a series of regression models testing relationships with different forms of inappropriate negotiation practices. All three variables (relativism and Machiavellianism working in tandem) were found to be appropriately associated with the five types of practices to some extent. The most interesting observation however was the recognition that idealistic orientations tended to influence attitudes more in situations involving direct negotiations, while the other, perceived negative attributions, tended to influence decision making more where the negotiations involved third parties.

Ethical climate types and their relationship to ethical orientations and judgement making

Hunt et al. (1989, 79) defined organisational ethical values as…“a composite of the individual ethical values of managers and both the formal and informal policies on the ethics of the organisation”. Douglas et al. (2001, 105) regarded them as…“the most important deterrent to unethical behaviour” and play a leading role in corporate governance (Schwartz et al. 2005). One recent China-based research paper by Shafer (2008) explores the relationship between ethical climate types within the workplace and the ethical ideologies and judgement making of a sample of auditors employed in local and international firms. Schafer applied his research agenda to a sample of 128 senior and manager level employees from a number of Mainland firms. In addition to using the EPQ to measure relativism and idealism, he also had subjects complete Victor and Cullen’s (1988, 1990) Ethical Climate Questionnaire (ECQ) in order to gauge the extent to which they believed their work environment reflected the nine conceptualised climate types. The findings were engaging and probably reflect a universal pattern, regardless of cultural underpinnings. The fact that the study involved a sample of Chinese members of the CICPA makes it particularly relevant to this study.

Schafer completed a regression analysis of data, which revealed no main effects of idealism or relativism on judgement or intentions; however, an interactive effect of both relativism and the egoistic climate type with respect to judgement making was noted. That is, the judgement making of auditors professing to work in an egoistic environment was likely to be significantly influenced by those who also scored high on the relativist scale.

Another related instrument that has been widely used in identifying an organisation’s ethical culture is Hunt et al.’s (1989) Corporate Ethical Values scale. They summarised organisational ethical values into two dimensions: (1) unethical workplace behaviours and (2) extant punishment systems. Prior studies show that by adopting an ethical tone, top management helps others within an organisation deal with moral hazards. (Finn et al. 1988) A copy of the scale instrument is provided in Appendix 2. The instrument has been applied in the study of collectivist societies (Marta and Singhapakdi 2005; Singhapakdi et al. 1999), but not Mainland China.

Hypothesis development

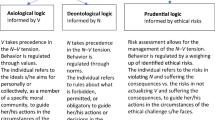

This paper pays attention to the moral positioning of Chinese certified auditors according to the ideological constructs derived by Forsyth (1980) in the context of the EPQ. Ethical orientations, described as the interplay of relativist and idealist notions about what is right and wrong, are subsumed within a package of heuristics that form part of a worldview about how moral dilemmas ought to be viewed and play a role in the process of decision making and subsequent behaviour (Al-Khatib et al. 2007). The constructs are underpinned by deontological and teleological considerations, but ethical positions adopted with respect to issues may not form part of a conscious evaluative process in the same way as described by other theorists, for example Hunt and Vitell (1986, 1993), Rest (1986) and Kohlberg (1969). Regardless of which methodology is adopted however, deliberations can be confused and distracted by a variety of psychological influences (e.g. ego strength, exogenous motivational and intensity issues). In order to determine the extent to which the two constructs effect judgement making, it is therefore imperative that it include a test of the veracity of the EPQ as an instrument explaining idealism and relativism.

In their recent meta-analytic investigation of cultural variations in idealism and relativism between 29 nations, Forsyth et al. (2008) described the Chinese as falling within the Subjectivist sub-category where, as a group (five samples totalling 1,081), the average respondent identified highly with the relativist position, and low on idealism. Using the same method of measurement, the following hypothesis is proposed.

-

H1:

On average, Chinese auditors display ethical orientations that would identify them as Subjectivists (i.e. low on idealism and high on relativism scales) within the scale defined by Forsyth ( 1980 ).

In this study, it was possible to survey the orientations of auditors from four large population centres, namely Beijing, Shenzhen, Hangzhou and Kunming. All three centres have industrial areas within their borders; however, economic growth has been most evident in Shenzhen and Beijing and to a lesser extent in the coastal city of Hangzhou. Kunming, the capital of the southwest province of Yunnan, has grown less dramatically since the opening up of China and is probably representative of the older socialist regime where the westernisation process is less evident. According to Redfern and Crawford (2004) and Redfern (2005), Chinese managers in different regions (i.e. based on geographic location and degree of industrialisation respectively) display variations in ethical ideology, demonstrating on average a Situationist perspective. Given these variations, it is anticipated that Chinese auditors employed in the four centres will also identify differently with respect to the constructs of idealism and relativism.

-

H2:

Chinese auditors employed in different population centres demonstrate significant differences in their idealistic and relativistic orientations.

Cultural factors likely to influence the extent to which people adopt ethical orientations were discussed by Forsyth et al. (2008). The Hofstede cultural elements relevant to Chinese executives in particular are covered in the Douglas and Weir’s (2005) paper. These aspects are accepted as given for the purposes of this study; however, it needs to be appreciated that various, possibly universal workplace factors play a role in the formation of belief systems. For example, in his study of Chinese auditors, Shafer (2008) discovered that perceptions of the existence of egoistic workplace environments interacted with relativistic orientations to affect judgement making. It is suggested that workplace policies and practices affect the attitudes that employees develop towards their work and that this influences the extent to which they adopt idealistic and relativist orientations and affects the way they view ethical dilemmas. These relationships will be explored in this study by using Hunt et al.’s (1989) Corporate Ethical Values scale, which examines the views that employees hold with respect to unethical workplace practices and extant punishment systems. To this end, the following hypotheses are proposed, which examine the direct effect of these views on ethical orientations as well as their effect on ethical judgement.

With respect to ethical orientations:

-

H3:

The more Chinese auditors agree that unethical workplace practices exist the more likely they are to adopt higher relativistic positions.

-

H4:

The more Chinese auditors agree that their firm has adequate punishment systems in place limiting unethical workplace practices the more they will be disposed to adopting idealistic positions.

With respect to ethical judgements:

-

H5:

The more Chinese auditors adopt relativistic positions the more they are likely to judge ethical issues involving problems of independence and objectivity leniently.

-

H6:

The more Chinese auditors adopt idealistic positions the less they are likely to judge ethical issues involving problems of independence and objectivity leniently.

-

H7:

The more Chinese auditors agree that unethical practices exist in their work place the more likely they are to be disposed to taking a lenient view of ethical issues that involve problems of independence and objectivity.

-

H8:

The more Chinese auditors agree that suitable punishment systems are in place within their workplace the more likely they are to take a less lenient view of ethical issues that involve problems of independence and objectivity.

Issues involving independence and objectivity are fundamentally important to the auditor in the conduct of their daily duties. The research literature identifies direct and indirect links between the ethical tone within an organisation and the judgements of employees while recognising the effect these have on the ethical positions adopted by them. The above tests aim to identify the extent to which these associations are exercised in the minds of practising Chinese auditors.

Methodology and data collection

A field survey methodology is used in this study. The survey instruments included a self-administered questionnaire and a short auditing ethical case. The questionnaire includes demographic information, Ethics Position and Corporate Ethical Values questionnaires. A Chinese expert (who speaks fluent English and Mandarin) was engaged to translate the scales from English to Chinese. Another Chinese expert then translated the scales back to English from Chinese to ensure equivalence in both languages.

As described earlier, a sample of Chinese auditors was drawn from local accounting firms in Shenzhen, Hangzhou, Beijing and Kunming cities. The data collection was supported by branches of CICPA located in each city. A covering letter and questionnaire were emailed to the Secretaries-General of these professional bodies. Copies of the instrument were printed and distributed to auditors registered with the CICPA during training sessions and conferences. Completed papers were subsequently collected and posted back to the authors. An effort was made to obtain usable questionnaires from a representative sample of China regions. Agents acting on behalf of the researchers indicated that auditors were expected to take the instrument seriously and made every effort to collect them during group meetings, limiting the effect of a non-response bias. Social desirability bias was limited as respondents were assured of the anonymity of responses.

The auditing ethical case, adapted from the American Accounting Association (1992; see Roxas and Stoneback 1997) and modified to suit Chinese subjects, was used to examine auditors’ ethical judgements. This case was chosen because it deals with an ethical conflict involving independence and objectivity, problems commonly experienced by auditors. Finn et al. (1988, p. 606) claim that…“ethical conflict occurs when people perceive that their duties toward one group are inconsistent with their duties and responsibilities toward some other group (including one’s self)”. The conflict is identified in the seven related questions. The first four deal with judgements, while the remaining three examine intention. The details of the case and the questions are provided in Appendix 3.

During late 2006, a total of 612 usable questionnaires were received from the four regional offices of the CICPA. Details of the basic percentage demographics making up the samples from each region are provided in Table 1. It is evident from the samples that CPAs working in Shenzhen are clearly younger than their counterparts in other regions and occupy relatively less senior positions. This is probably indicative of the fact that the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone was probably the fastest growing region at the time and attracts young people from all over China. Gender was equally represented in all regions and similarly distributed within the overall sample.

Psychometric data collected with respect to the three instruments are summarised for the overall Chinese sample in Table 2 and were subjected to tests of reliability and consistency. Scoring was reversed as necessary and one of the original eight case study questions relating to attitudes was deleted.

Data for each of the two constructs making up the EPQ were subject to reliability tests and produced satisfactory Cronbach alpha scores of 0.88 and 0.83 for idealism and relativism scales, respectively, similar to those acquired in most other studies (Forsyth et al. 2008). Comparative data and construct validation are discussed in greater detail in the “Results of tests of hypotheses” section of this paper; however, two issues that require prior attention relate to the scoring and representation of data. In their meta-analytic study, Forsyth et al. (2008) identified that many prior studies had used a variety of approaches to collect and analyse data relating to the EPQ. In this study, responses to all twenty questions making up the EPQ were included and responses measured using a nine-point Likert scale (the same as that used in the original Forsyth (1980) study). Where possible, information relating specifically to idealism and relativism is provided in terms of scores that can be compared with that reported in the Forsyth et al. (2008) meta-analysis, although it was felt necessary to use standardised values in regression tests conducted with respect to the various hypotheses. The object here was to reduce the effect of extreme scoring, given the size of the scale (Hair et al. 1995).

The Hunt et al. (1989) Corporate Ethical Values scale (refer Appendix 2) has been widely applied in prior studies (e.g. Douglas et al. 2001; Singhapakdi et al. 1999; Vitell and Hidalgo 2006). These studies used the average score of all five items to measure perceptions about corporate ethical values. In this study, the scale was developed based on two considerations, and it is believed that they provide better insights into the auditors’ views about their firms’ ethical climate. By subjecting questionnaire responses to an exploratory factor analysis with rotation (Direct Oblimin), two factors explaining 71.5% of the variance were extracted. Questions 3–5 load significantly on factor 1 (explaining 39% of the variance) and is named punishment systems. Items 1 and 2 load significantly on factor 2 (33% of the variance) and is named unethical workplace practices.

An examination of the seven questions contributing to the variable explaining ethical judgement in relation to an audit dilemma (refer Appendix 3) showed that respondents were consistent in the way they interpreted the issues. After adjusting a number of reverse scored questions, a Cronbach alpha test established an acceptable reliability index of 0.74. Key psychometric data are summarised in Table 2 by region.

Results of tests of hypotheses

Veracity of EPQ as an instrument identifying measures of idealism and relativism

Limitations with respect to the use of all original EPQ items to represent the constructs for idealism and relativism are discussed in the Forsyth et al. (2008) paper. Davis et al. (2001) and Cui et al. (2005) conducted a factor analysis on the 20 items to identify which best describe the two dimensions, and the results had them disregarding some of the items. In this study, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted, and the reductive process resulted in two dimensions after eliminating items 1 and 7 from the idealism scale and items 11, 12, and 16–18 from the relativism scale. After examining the remaining items (forming two constructs within each set), it was felt that they continued to describe the objects as prescribed in the original instrument.

A satisfactory goodness of fit was attainable with a significantly large X 2 statistic (CMIN) approximating the observable degrees of freedom (refer Table 3). Test output resulting from the SEQ analysis conducted on the China sample provided indices for a well-fitting hypothesised model (Byrne 2001).

On the basis of this result, it is contended that independent indices that adequately describe idealism and relativism appear to exist, and the remaining EPQ items are used in later regression analyses.

Ideological typing of Chinese auditors

Forsyth et al. (2008) identified its Chinese sample as Subjectivists, scoring relatively low on idealism and high on relativism. Using information provided in the Forsyth et al. (2008) meta-analysis, one-sample t tests were conducted to establish whether average idealism and relativism scores for Chinese auditors approximate the median for all sample nations or scores determined for the China sub-sample. Results are listed in Table 4. The analysis clearly identifies significant differences between sample indices for both sets of comparisons. Using Forsyth’s classification model, Chinese auditors do not appear to be Subjectivists (closer to being labelled Exceptionists if the model provided by Forsyth et al. (2008) is applied). The hypothesis H1 stating that Chinese auditors can be labelled as Subjectivists is therefore rejected.

Regional differences in idealism and relativism

Table 2 provides psychometric data for idealism and relativism within the four regions included in this study of Chinese auditors. A one-way ANOVA of the sub-groups resulted in there being no significant differences (p < 0.05) in mean scores. The outcome remained unchanged when the revised EPQ construct mean scores were used in the analysis. Location of employment is not a factor distinguishing ideological orientation in this study and results in hypothesis H2 being rejected.

Attitudes in relation to workplace ethics and effect on orientation

In his study, Shafer (2008) identified ethical climate types as likely to affect the extent to which Chinese auditors adopt ideological positions. In this study, two constructs identified from the Corporate Ethical Values scale (i.e. existence of unethical workplace practices and punishment systems) were used as predictors in regression analyses along with other available personal demographics (refer Table 1). A stepwise regression was applied in tests for both idealism and relativism, which resulted in significant stable models with no evidence of autocorrelation in the residuals. Results are summarised in Table 5.

The influences of both the positive and negative aspects of the workplace environment are logically associated with what are perceived to be equivalent positive and negative orientation constructs. Firstly, the more auditors envisage appropriate punishment systems are in place within their workplace, the more likely they are to adopt idealistic orientations. And the more they perceive the existence of unethical workplace practices, the more they are likely to adopt relativistic orientations. These outcomes support the hypotheses H3 and H4 and will have repercussions when viewed as predictors of moral judgement. It is interesting to note that age also influences orientation. Younger auditors are more likely to embrace relativistic views, while older (more senior auditors) tend to adopt idealistic perspectives.

Influences on moral judgement of Chinese auditors

All the matters addressed in hypotheses H5 to H8 can be reviewed in a further regression test that examines the joint effect of personal demographics, ethical orientations and perceived workplace environments on ethical judgement as measured by the responses provided with respect to the ethical dilemma (Appendix 3). The Regression results (using Stepwise method) including significant outcomes are provided in Table 6.

A fairly robust model emerges from the regression explaining almost 13% of the variance in the dependent variable, moral judgement. Idealism and unethical workplace practices are the major offsetting predictors of moral judgement. Auditors expressing higher idealistic orientations are likely to be less lenient in their attitudes towards workplace issues that involve problems affecting independence and objectivity (hypothesis H5 supported). Hypothesis H6 is also supported, in that auditors expressing higher relativistic orientations are more likely to view unethical workplace issues leniently. However, the contribution to the overall multivariate model appears marginal.

Not unexpectedly, auditor perspectives on the extent to which the workplace environment appears to condone unethical practices have a strong negative influence on ethical judgement (hypothesis H7 supported), and this is again offset to a limited extent by views about the effectiveness of the firm’s policy towards the existence of these practices (hypothesis H8 supported). Interestingly, the position or level of appointment emerges as a positive contributor within the regression model. This variable correlates strongly with age and suggests that persons in more senior positions are likely to express greater concern about unethical workplace attitudes and actions that threaten their professional status.

Discussion and conclusion

In the introduction to this paper, attention was given to discussing reports from various sources highlighting concern about high levels of corruption in Chinese business and the responsibility this imposes on the nation’s fledgling accounting profession, namely the CICPA and its 140,000 members. They undoubtedly face issues that threaten independence and objectivity on a regular basis as they engage with local and international business firms. In recent years, a number of accounting firms and individuals have been brought to account by the central government authorities as a result of their involvement in various illegal practices. These concerns raise the question as to how the profession will cope especially as business activity in China continues to explode. Under these circumstances, can this independent professional governance agency continue to provide the necessary assurance its local and international stakeholders demand? Does it face a credibility crisis?

This study of 612 registered auditors employed in local firms aims to address these concerns by focusing on two factors affecting the moral beliefs and attitudes of Chinese auditors, namely their personal ethical orientations (as originally described by Forsyth (1980)) and their individual impressions about the ethical tone affecting workplace conditions. In their meta-analytic study of ethical orientations, Forsyth et al. (2008) made it clear that the EPQ was not without its problems and that care should be taken in its application and interpretation. However, many researchers continue to use the instrument in their surveys, and the authors of this study also express confidence about its utility as an indicator of moral predisposition. The positional concepts it identifies, namely idealism and relativism, have relevance in their own right and, when applied to a sample of Chinese auditors confirmed what most studies in other areas have found that ethical orientations influence judgement.

Nevertheless, when reviewing the literature, it becomes apparent that the concepts of idealism and relativism raise some issues which the authors would like to express for the benefit of other users. Firstly, as identified by Forsyth et al. (2008), the concepts do not occupy opposing ends of the same continuum. At the same time however, they may be somewhat related (e.g. intercorrelation for the standardised variables in this study was found to be 0.155). The two sets of ten questions clearly expose subjects to extreme situations, and in most cases, respondents find themselves adjusting downwards along respective Likert scales. It is suggested that the majority of people accept most aspects of the deontological argument (i.e. the need for rules and regulations for the benefit of society) and contiguously find benefit in aspects of the teleological process allowing them (in theory) to consider the circumstances and consequences of their actions. When making a moral judgement, trade-offs between the two sets of views are inevitable (justifying some correlation), and it is therefore the extent of the trade-off which is relevant in the analysis. EPQ scores and the group labelling of respondents have less bearing in the decision-making process. It is the heuristic that the respondent applies when considering a moral issue which is important.

Researchers often describe relativists and idealists as if they were two separate groups of people in their study and present their findings accordingly. The reality is however, and this is predicated in Forsyth’s (1980) four group taxonomy, that one group of people hold varying positions with respect to the same two variables. Depending on the way the 2 × 2 matrix of types is constructed (e.g. Redfern (2005) used the mid-point along a nine-point scale), it is likely that the majority of subjects will be classified as Situationists. In the decision-making process, it is the extent of the trade-off that occurs between competing heuristics, which determines the direction of the mental process and the behaviour attending it. Again, the labelling of individuals as Situationist, Subjectivist, Exceptionist or Absolutist holds less importance and is difficult to substantiate from the literature.

Because of the importance of idealism and relativism as conceptual representatives of ethical position, much attention was given in this study to establish whether they were properly identified within the EPQ when applied to Chinese auditors. A Confirmatory Factor Analysis (using AMOS) established the veracity of the instrument, although it was found necessary to exclude a number of items as part of the process of achieving a satisfactory goodness-of-fit (consistent with Davis et al. (2001) and Cui et al. (2005)). Before using the adjusted variables as criterion variables in a regression analysis, a test was conducted which established that this group of Chinese auditors were not classifiable as Subjectivists as determined in the meta-analytic study of 29 nations (Forsyth et al. 2008). They recorded significantly lower average scores for both idealism and relativism. In reference to the preceding discussion, any change in labelling holds relatively little importance in the context of the major objectives of this paper.

A comparison of results from four different business regions in China did not produce any significant differences in ethical position even after noting that the sample of auditors from Shenzhen was much younger than for the other regions and they occupied less senior positions on average. This issue will have relevance when the results of the regression analysis are discussed.

The Corporate Ethical Values scale developed by Hunt et al. (1989) was included in this field study as a useful way to gauge the ethical tone within local Chinese accounting firms, in that it afforded auditors an opportunity to indicate the extent to which unethical practices were tolerated and whether they believed the firms’ policies in this area (i.e. punishment process) were adequate. More importantly, it was demonstrated that the variables, as constructs derived from exploratory factor analysis, were instrumental in influencing both the ethical orientation of auditors as well as the moral judgements of auditors. The regression analyses illustrated in Tables 5 and 6 above affirm the role which each construct plays in the formation of heuristics associated with moral issues. Of particular concern is the effect of unethical workplace practices. The more these practices are seen to be tolerated, the more likely auditors will adopt extreme relativistic positions and also be more lenient in their attitudes towards ethical issues that challenge their independence and objectivity. Admittedly for the sample as a whole, these inclinations are likely to be offset by the benefits associated with adopting higher idealistic positions and working in firms that have appropriate punishment systems in use. However, the threat with respect to auditors making inappropriate actions in practice is clearly evident and is related directly to their ethical orientations. The ethical tone in Chinese firms needs to be such as to act as a deterrent to unethical and illegal decision making.

Within a regional context, the threat is probably greatest in the Shenzhen, where relatively younger auditors (employed in lower positions) are likely to adopt higher relativistic and lower idealistic positions as a result of the way they view workplace practices. It could be argued however that older more senior officers may use positive influences to deter or override the decisions of their younger staff. This is an area that deserves further research.

This research study suffers the same limitations as others using the EPQ, in that it needs to be properly administered and effectively utilised in the process of determining ethical orientations. Furthermore, ethical orientations are just part of a larger heuristic that Chinese auditors are likely to employ when making moral choices in practice. Issues of motivation (e.g. agency problems, intensity of issues, external factors, etc.) and character are also of equal importance in the decision-making process.

Finally, how is it possible to address the questions raised in the introduction to this discussion? This study has identified the critical role that ethical climate types play in influencing the attitudes of Chinese accountants. The ethical tone needs to be high at all levels of operation, and hopefully, this can be effected through appropriate policies and practices, including the employment of CICPA members who come encouraged and empowered by the support and training offered by a vibrant and effective professional body.

References

Al-Khatib, J. A., Vollmers, S. M., & Liu, Y. (2007). Business-to-business negotiating in China: the role of morality. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 22(2), 84–96.

Barnett, T., Bass, K., & Brown, G. (1994). Ethical ideology and ethical judgment regarding ethical issues in business. Journal of Business Ethics, 13(6), 469–480.

Barnett, T., Bass, K., & Brown, G. (1996). Religiosity, ethical ideology, and intentions to report a peer’s wrongdoing. Journal of Business Ethics, 15(11), 1161–1174.

Barnett, T., Bass, K., Brown, G., & Hebert, F. J. (1998). Ethical ideology and the ethical judgment of marketing professionals. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(7), 715–723.

Bass, K., Barnett, T., & Brown, G. (1998). The moral philosophy of sales managers and its influence on ethical decision making. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 18(2), 1–17.

Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications and programming. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

China Commercial Banking Report. 2010. Business Monitor International March 2010.

Chinese Institute of Certified Public Accountants. 2007. An Introduction to the Chinese Institute of Public Accountants. http://www.cicpa.org.cn.

Chui, R. K., & Stembridge, A. F. (2001). How managers judge whether or not they want to report a peer’s unethical behavior. InFo, 4(1), 5–16.

Cui, C. C., Mitchell, V., Schlegelmilch, B. B., & Cornwell, B. (2005). Measuring consumers’ ethical position in Austria, Britain, Brunei, Hong Kong, and USA. Journal of Business Ethics, 62, 57–71.

Davies, M. A., Andersen, M. G., & Curtis, M. (2001). Measuring ethical ideology in business ethics: a critical analysis of the ethics position questionnaire. Journal of Business Ethics, 32, 35–53.

Dolecheck, M. M., and C. C. Dolecheck. 1987. Business ethics: a comparison of attitudes of managers in Hong Kong and the United States. The Hong Kong Manager April-May:28–43.

Douglas, P. C., & Schwartz, B. N. (1999). Values as the foundation for moral judgment: theory and evidence in an accounting context. Research on Accounting Ethics, 5, 3–20.

Douglas, P. C., & Wier, B. (2005). Cultural and ethical effects in budgeting systems: a comparison of U.S. and Chinese managers. Journal of Business Ethics, 61, 159–174.

Douglas, P. C., Davidson, R. A., & Schwartz, B. N. (2001). The effect of organizational culture and ethical orientation on accountants’ ethical judgment. Journal of Business Ethics, 34, 101–121.

Finn, D. W., Chonko, L. B., & Hunt, S. D. (1988). Ethical problems in public accounting: the view from the top. Journal of Business Ethics, 7, 605–615.

Forsyth, D. R. (1980). A taxonomy of ethical ideologies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(1), 175–184.

Forsyth, D. R., O’Boyle, E. H., & McDaniel, M. A. (2008). East meets west: a meta-analytic investigation of cultural variations in idealism and relativism. Journal of Business Ethics, 8(83), 813–833.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1995). Multivariate data analysis with readings (4th ed.). Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Hampden-Turner, C., and F. Trompenaars. 1993. The Seven Cultures of Capitalism: Piatkus, London.

Hartikainen, O., & Torstila, S. (2004). Job-related ethical judgment in the finance profession. Journal of Applied Finance (JAF), 14(1), 62–76.

Hofstede, G. H. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hill: Sage.

Hunt, S. D., & Vitell, S. J. (1986). A general theory of marketing ethics. Journal of Macromarketing, 6, 5–16.

Hunt, S. D., and S. J. Vitell. (1993). The general theory of marketing ethics: A retrospective and revision. In N. Smith and J. Quelch. (Eds), Ethics in marketing. Boston: Richard D. Irwin, Chicago IL.

Hunt, S., Wood, V., & Chonko, L. (1989). Corporate ethical values and organisational commitment in marketing. Journal of Marketing, 53, 79–90.

Jackson, T. C., Deshpande, D. S., Jones, J., Joseph, J., & Lau, K. (2000). Making ethical judgements: a cross-cultural management study. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 17, 443–472.

Kohlberg, L. (1969). Moral stages and moralisation: the cognitive-development approach to socialisation. In D. Goskin (Ed.), Handbook of socialization theory and research. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Kohlberg, L. (1981). The Philosophy of Moral Development, New York: Harper & Row.

Marques, P. A., & Azevedo-Pereira, J. (2009). Ethical ideology and ethical judgments in the Portuguese accounting profession. Journal of Business Ethics, 86, 227–242.

Marta, J. K., & Singhapakdi, A. (2005). Comparing Thai and US businesspeople: perceived intensity of unethical marketing practices, corporate ethical values, and perceived importance of ethics. International Marketing Review, 22(5), 562–578.

Ralston, D. A., Gustafson, D. J., Terpstra, R. H., & Holt, D. H. (1995). Pre-post Tiananmen square: changing values of Chinese managers. ASIA Pacific Journal of Management, 12(1), 1–20.

Redfern, K. (2005). The influence of industrialization on ethical ideology of managers in the People’s Republic of China. Cross Cultural Management, 12(2), 38–50.

Redfern, K., & Crawford, J. (2004). An empirical investigation of the ethics position questionnaire in the People’s Republic of China. Journal of Business Ethics, 50, 199–210.

Rest, J. R. (1986). Moral development: Advances in research and theory. New York: Praeger.

Robertson, C. J., Olson, B. J., Gilley, M., & Bao, Y. (2008). A cross-cultural comparison of ethical orientations and willingness to sacrifice ethical standards: China versus Peru. Journal of Business Ethics, 81, 413–425.

Roxas, M. L., & Stoneback, J. Y. (1997). An investigation of the ethical decision-making process across varying cultures. The International Journal of Accounting, 32(4), 503–535.

Schlenker, B. R., & Forsyth, D. R. (1977). On the ethics of psychological research. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 13, 369–396.

Schwartz, M. S., Dunfee, T. W., & Kline, M. J. (2005). Tone at the top: an ethics code for directors? Journal of Business Ethics, 58, 79–100.

Shafer, W. E. (2008). Ethical climate in Chinese CPA firms. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33, 825–835.

Shaub, M. K., Finn, D. W., & Munter, P. (1993). The effects of auditors’ ethical orientation on commitment and ethical sensitivity. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 5, 145–169.

Shi, S., & Weisert, D. (2002). Corporate Governance and Chinese characteristics. The Chinese Business Review, 29(5), 40-45.

Singhapakdi, A., Higgs-Kleyn, N., & Rao, C. P. (1999). Selected antecedents and components of ethical decision-making processes of American and South African markers—a cross-cultural analysis. International Marketing Review, 16(6), 458.

Singhapakdi, A., Salyachivin, S., Virakul, B., & Veerayangkur, V. (2000). Some important factors underlying ethical decision making of managers in Thailand. Journal of Business Ethics, 27(3), 271–287.

Snell, R., & Tseng, C. S. (2002). Moral atmosphere and moral influence under China’s network capitalism. Organization Studies, 23(3), 449–478.

Swoler, C. 2003. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/relativism/.

Tai, K. Corporate Governance Study 2003 [cited]. Available at: http://icf.yale.edu/research/china/newpage/cn/feature/mainland/corporate%20governance%20in%20china.htm.

Tang, Y. (1999). Issues in the development of the accounting profession in China. China Accounting and Finance Review, 1, 21–36.

Tansey, R., Brown, G., Hyman, M., & Dawson, L. (1994). Personal moral philosophies and the moral judgments of salespeople. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 14(1), 59–76.

Velasquez, M. G. (2006). Business Ethics: Concepts & Cases. Sixth Edition, London: Prentice Hall.

Victor, B., & Cullen, J. B. (1988). The organisational bases of ethical work climates. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33, 101–125.

Victor, B., & Cullen, J. B. (1990). A theory and measure of ethical climate in organisations, in Business Ethics. In Research Issues and Empirical Studies, edited by W. C. a. P. Frederick, L.E., Greenwich Con: JAI Press Inc.

Vitell, S. J., & Hidalgo, E. R. (2006). The impact of corporate ethical values and enforcement of ethical codes on the perceived importance of ethics in business: a comparison of U.S. and Spanish managers. Journal of Business Ethics, 64, 31–43.

Wakefield, R. L. (2008). Accounting and machiavellianism. Behavioural Research in Accounting, 20(1), 115–129.

Whitcomb, L., Erdener, C., & Li, C. (1998). Business ethical values in China and the US. Journal of Business Ethics, 17, 839–852.

Zhao, B. (2008). Consumer ethics: an empirical investigation of the ethical beliefs in Mainland China. The Business Review Cambridge, 10(1), 223–228.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: EPQ

-

1)

One should make certain that his/her actions never intentionally harm another even to a small degree.

-

2)

Risks to another should never be tolerated, irrespective of how small the risks might be.

-

3)

Potential harm to others is always wrong, irrespective of the benefits to be gained.

-

4)

One should never psychologically or physically harm another person.

-

5)

One should not perform an action which might in any way threaten the dignity and welfare of another individual.

-

6)

If an action could harm an innocent other, then it should not be done.

-

7)

Deciding whether or not to perform an act by balancing the positive consequences of the act against the negative consequences of the act is immoral.

-

8)

The dignity and welfare of people should be the most important concern in any society.

-

9)

It is never necessary to sacrifice the welfare of others.

-

10)

Moral actions are those which closely match the ideal of the most ‘perfect’ action.

-

11)

There are no ethical principles that are so important that they should be part of any code of ethics.

-

12)

What is ethical varies from one situation and society to another.

-

13)

Moral standards should be seen as being individualistic; what one person considers to be moral may be judged to be immoral by another person.

-

14)

Different types of moralities cannot be compared as to ‘rightness.’

-

15)

Questions of what is ethical for everyone can never be resolved since what is moral or immoral is up to the individual.

-

16)

Moral standards are personal rules which indicate how a person should behave, and are not to be applied in judging others.

-

17)

Ethical considerations in interpersonal relations are so complex that individuals should be allowed to form their own codes.

-

18)

Rigidly codifying an ethical position that prevents certain types of actions could stand in the way of better human relations and adjustment.

-

19)

No rule about lying can be formulated; whether a lie is permissible or not permissible depends upon the situation.

-

20)

Whether a lie is judged to be moral or immoral depends upon the circumstances surrounding the action.

*Measured on a nine-point (9) response scale from Strongly disagree (1) to Strongly agree (9). Source: Forsyth (1980)

Appendix 2: Corporate Ethical Values scale (CEV)*

-

1.

Managers in my firm often engage in behaviours that I consider to be unethical

-

2.

In order to succeed in my firm, it is often necessary to compromise one’s ethics

-

3.

Top management in my firm has let it be known that unethical behaviours will not be tolerated

-

4.

If a manager in my firm is discovered to have engaged in unethical behaviour that results primarily in personal gain (rather than firm gain), he or she will be promptly reprimanded

-

5.

If a manager in my firm is discovered to have engaged in unethical behaviour that results in firm gain (rather than personal gain), he or she will be promptly reprimanded

*Measured on a seven-point (7) response scale from Strongly disagree (1) to Strongly agree (7). Source: Hunt et al., (1989)

Appendix 3: Auditing case for assessing ethical judgement

XYZ is a five-year old private company. During the 5 years, the business has grown substantially and has generated a comfortable living for its owner and CEO, Mr. Li. In order to grow further, Mr. Li is considering expanding by applying for a loan from the Bank of China to increase capital.

The bank requires an independent auditor’s review as part of the loan approval process. The company has failed, as many closely held businesses do, to keep careful records. Until now, XYZ has not had an outside accountant.

After completing the current year’s review, CPA Wong tells Mr. Li that the company has incurred a loss of $125,000. Mr. Li comments to him, “You know, if the Bank of China sees these statements, we’ll never get the line of credit”. CPA Wong assures him that the company still has significant net worth despite a bad year. So he does not think that the Bank of China will reject the loan application over the 1-year loss. Mr. Li is not convinced; the bank manager made it clear that he would take a close look at current performance prior to extending the line of credit. If the credit is not forthcoming, XYZ will have a hard time paying suppliers on time. If materials or parts are held up, delivery deadliness will not be met and the income situation will deteriorate further. Mr. Li asks, “CPA Wong, how can we make this look better? You accountants know various ways of interpreting and reporting data. Certainly you know how to change the numbers to present a better picture. Can’t the undervalued assets be restated? What about all that goodwill we have generated by quality products and prompt service? That must be worth something. What about receivables? Maybe all those accounts that you wrote off weren’t all that bad; perhaps we could carry some of them for a while longer. Tell me, what can we do now?”

Mr. Li’s attitude makes CPA Wong uneasy. At the same time, XYZ is in an industry where CPA Wong’s accounting firm has been trying to gain a foothold for some time. The XYZ account could mean as much as 25% of his firm’s income in terms of opportunities for service alone. In today’s competitive market, every prospective client is valuable.

Required: Using your own experience as a basis, respond to the following questions as if you were in CPA Wong’s situation. Please circle the one number which best answer describes your view of each question.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Woodbine, G., Fan, Y.H. & Scully, G. The ethical orientations of Chinese auditors and the effect on the judgements they make. Asian J Bus Ethics 1, 195–216 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-011-0001-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-011-0001-5