Abstract

Internet retailers often make use of price search services (infomediaries) that have the effect of reducing consumer search and expanding seller market presence. Research on price and advertising suggests that this may not be a profitable strategy. We develop an experimental posted-offer market to estimate the impact of infomediaries on price of homogenous goods. We analyze panel data from a range of market conditions that address how infomediaries services affect both seller-level offered price as well as market-level transacted price. We find that, while sellers attempt to extract higher prices through a higher initial offer price when using an infomediary, they fail to successfully collect it; transacted prices remain largely unchanged. As a consequence the benefits of infomediaries fall primarily to the buyer who faces largely unchanged transacted prices, and substantially reduced search costs. Search costs are, in essence shifted to the seller. Sellers who participate in this sort of price comparison should be aware that they are following a high-volume/low profit per unit strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We thank the anonymous reviewer for suggesting this comment.

References

Bakos, J. Y. (1991). A strategic analysis of electronic marketplaces. MIS Quarterly, 15(3), 295–310.

Bakos, J. Y. (1997). Reducing buyer search costs: implications for electronic marketplaces. Management Science, 43(12), 1613–1630.

Bapna, R., Goes, P., & Gupta, A. (2003). Replicating online Yankee auctions to analyze auctioneers’ and bidders’ strategies. Information Systems Research, 14(3), 244–268.

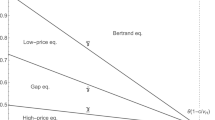

Baye, M. R., & Morgan, J. (2001). Information gatekeepers on the internet and the competitiveness of homogeneous product markets. American Economic Review, 19(3), 454–474.

Brannon, J., & Gorman, M. (2002). The effect of information costs in experimental posted markets. Journal of Economic and Behavior and Organization, 47(4), 375–390.

Brynjolfsson, E., & Smith, M. D. (2000). Frictionless commerce. A comparison of internet and conventional retailers. Management Science, 46(4), 563–585.

Chin, W. W., Gopal, A., & Salisbury, W. D. (1997). Advancing the theory of adaptive structuration: the development of an instrument to measure faithfulness of appropriation of an electronic meeting system. Information Systems Research, 8(4), 342–367.

Clemons, E. K., Hann, I. H., & Hitt, L. M. (2002). Price dispersion and differentiation in online travel: an empirical investigation. Management Science, 48(4), 534–549.

Davis, D. and A. Williams (1986). The effects of rent asymmetries in posted-offer markets. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, pp. 303-316.

Davis, D., Harrison, G., & Williams, A. (1993). Convergence to nonstationary competitive equilibria: an experimental analysis. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 22, 305–326.

Diamond, P. (1971). A model of price adjustment. Journal of Economic Theory, 3, 156–168.

Dickson, P. R., & Sawyer, A. G. (1990). The price knowledge and search of supermarket shoppers. Journal of Marketing., 54(3), 42–53.

Ehrlich, I., & Fisher, L. (1982). The derived demand for advertising: a theoretical and empirical investigation. The American Economic Review, 72(3), 366–388.

Farris, P., & Albion, M. (1980). The impact of advertising on the price of consumer products. Journal of Marketing, 44, 17–35.

Ferguson, J. M. (1982). Comments on ’The Impact of Advertising on the Price of Consumer Products’. Journal of Marketing, 46, 102–105.

Greenwald, A, and J. J. Kephart (1999). Shopbots and pricebots. Proceedings of International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence 1999.

Grover, V., & Ramanlal, P. (1999). Six myths of information and markets: Information technology networks, electronic commerce, and the battle for consumer surplus. MIS Quarterly, 23(4), 465–495.

Hagel, J., & Singer, M. (1999). Net worth: Shaping markets when customers make the rules. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Hitt, L. M., & Brynjolfsson, E. (1996). Productivity, business profitability, and consumer surplus: three different measures of information technology value. MIS Quarterly, 20(2), 121–142.

Ketcham, J., Smith, V., & Williams, A. (1984). Comparison of posted-offer and double-auction pricing institutions. Review of Economic Studies, 51, 595–614.

Kocas, C. (2003). Evolution of prices in electronic markets under diffusion of price-comparison shopping. Journal of MIS, 19(3), 99–119.

Lee, H. G. (1998). Do electronic marketplaces lower the price of goods? Communications of the ACM, 41(1), 73–80.

Lynch, J. G., & Ariely, D. (2000). Wine online: search costs affect competition on price quality and distribution. Marketing Science., 19(1), 83–204.

Narasimhan, C. (1988). Competitive promotional strategies. Journal of Business, 61(4), 427–449.

Nelson, P. (1970a). Information and consumer behavior. Journal of Political Economy. Vol., 78(3), 311–329.

Nelson, P. (1974). Advertising as information. Journal of Political Economy, 82, 729–754.

Nelson, I. (1970b). Information and consumer behavior. Journal of Political Economy, 78, 311–29.

Porter, M. E. (2001). Strategy and the internet. Harvard Business Review, 79(3), 63–78.

Riquelme, H. (2001). An empirical review of price behaviour on the internet. Electronic Markets, 11(4), 263–272.

Robert, J., & Stahl, D. (1993). Information price advertising in a sequential search model. Econometrica, 61, 657–686.

Salisbury, W. D., Chin, W. W., Gopal, A., & Newsted, P. R. (2002). Better theory through measurement: developing a scale to capture consensus on appropriation. Information Systems Research, 13(1), 91–103.

Schwartz, Robert A., & Weber, B. W. (1997). Next-generation securities market systems: an experimental investigation of quote-driven and order-driven trading. Journal of Management Information Systems, 14(2), 57–80.

Simon, H. A. (1957). Models of man. New York: Wiley.

Smith, V. (1962). An experimental study of competitive market behavior. Journal of Political Economy, 70, 111–137.

Smith, V. (1964). Effect of market organization on competitive equilibrium. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 78, 181–201.

Smith, M., Bailey, J., & Brynjolfsson, E. (2000). Understanding digital markets. In E. Brynjolfsson & B. Kahin (Eds.), Understanding the Digital Economy, pp. 99–136. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Soberman, D. A. (2004). Research note: additional learning and implications on the role of informative advertising. Management Science, 50(12), 1744–1750.

Tellis, G. (1988). The price elasticity of selective demand: a meta-analysis of econometric models of sales. Journal of Marketing Research, 25, 331–41.

Vanhonacker, W. (1989). Modeling the effect of advertising on price response: an econometric framework and some preliminary findings. Journal of Business Research, 19, 127–149.

Varian, H. (1980). A model of sales. American Economic Review, 70(4), 210–223.

Varian, H. (2005). Intermediate microeconomics: A modern approach, Seventh Edition. Inc: W. W. Norton & Co.

Williams, A., & Walker, J. (1993). Computerized laboratory exercises for microeconomics education. Journal of Economic Education, 24, 291–315.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Rolf T. Wigand

An earlier version of this manuscript was presented at the Conference of the Administrative Sciences Association of Canada, Information Systems Division.

Appendix−Summary instructions for buyers and sellers

Appendix−Summary instructions for buyers and sellers

SUMMARY OF BUYER INSTRUCTIONS | SUMMARY OF SELLER INSTRUCTIONS |

1. The experiment takes place over a number of Trading Periods. | 1. The experiment takes place over a number of Trading Periods. |

2. For each unit you buy, you will receive the difference between the Resale value of that unit and its Purchase price. | 2. For each unit you sell, you will receive the difference between your Selling Price and the Production Cost for that unit. |

3. SELLERS begin each period by offering a price and a number of units for sale. | 3. SELLERS begin each period by offering a price and a number of units for sale. |

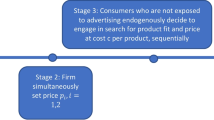

4. After SELLERS have made their offers, they will each be asked to advertise their prices to BUYERS. | 4. After all SELLERS have made their offers, they will be asked to advertise their prices to BUYERS. For each BUYER you elect to advertise to, you will be charged an advertising FEE. |

5. If a SELLER does not advertise to you, you wil be able to pay to see his price if you desire. | 5. If you do not advertise, BUYERS will still be able to pay to see you price. But if you do not advertise and a BUYER does not pay to see your price, you will not be able to sell any units to that BUYER. |

6. After SELLERS have finished advertising, BUYERS will be asked to pay to see SELLERS’ prices. You will be charged an Informatin Fee for each price you elect to reveal. Remember, if you cannot see a SELLER’s price, you will not be able to buy any units from him. | 6. After SELLERS have finished advertising, BUYERS will be asked to pay to see the prices of those SELLERS who did not advertise. |

7. To start the buying mode, the computer randomly selects a BUYER who will then be able to buy units. When you buy a unit, the computer automatically records the transaction for you in your record sheet. | 7. To start the buying mode, the computer randomly selects a BUYER who will then be able to buy units. If a BUYER purchases one of your units, the computer automatically records the sale on your record sheet. |

8. After each BUYER has been given a chance to purchase units, a new Trading Period will begin. | 8. After each BUYER has been given a chance to purchase units, a new Trading Period will begin. |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gorman, M.F., Salisbury, W.D. & Brannon, I. Who wins when price information is more ubiquitous? An experiment to assess how infomediaries influence price. Electron Markets 19, 151–162 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-009-0009-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-009-0009-z