Abstract

Combinations between an angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) and hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) are among the recommended treatments for hypertensive patients uncontrolled by monotherapy. Four randomized, double-blind, parallel group studies with a similar design, including 1469 hypertensive patients uncontrolled by a previous monotherapy and with ≥1 cardiovascular risk factor, compared the efficacy of a combination of a sulfhydryl ACE inhibitor (zofenopril at 30 or 60 mg) or an ARB (irbesartan at 150 or 300 mg) plus HCTZ 12.5 mg. The extent of blood pressure (BP)-lowering was assessed in the office and over 24 h. Pleiotropic features of the treatments were evaluated by studying their effect on systemic inflammation, organ damage, arterial stiffness, and metabolic biochemical parameters. Both treatments similarly reduced office and ambulatory BPs after 18–24 weeks. In the ZODIAC study a larger reduction in high sensitivity C reactive protein (hs-CRP) was observed under zofenopril (−0.52 vs. +0.97 mg/dL under irbesartan, p = 0.001), suggesting a potential protective effect against the development of atherosclerosis. In the ZENITH study the rate of carotid plaque regression was significantly larger under zofenopril (32% vs. 16%; p = 0.047). In the diabetic patients of the ZAMES study, no adverse effects of treatments on blood glucose and lipids as well as an improvement of renal function were observed. In patients with isolated systolic hypertension of the ZEUS study, a slight and similar improvement in renal function and small reductions in pulse wave velocity (PWV), augmentation index (AI), and central systolic BP were documented with both treatments. Thus, the fixed combination of zofenopril and HCTZ may have a relevant place in the treatment of high-risk or monotherapy-treated uncontrolled hypertensive patients requiring a more prompt, intensive, and sustained BP reduction, in line with the recommendations of current guidelines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Large intervention trials have shown that the majority of hypertensive patients may need a combination of two or more antihypertensive medications to achieve satisfactory blood pressure (BP) control and effective cardiovascular (CV) protection [1, 2]. This holds true particularly for patients at high risk for CV events, such as older individuals, patients with diabetes or the metabolic syndrome, co-existing CV disease, or other associated clinical conditions [3, 4]. According to the evidence provided by major intervention trials, current guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension acknowledge and recommend the use of combination treatment, particularly when BP control with initial monotherapy is inadequate [5–8].

Amongst the most effective two-drug antihypertensive combinations are those between an antagonist of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS), such as an angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB), and a thiazide diuretic. The mechanism of action of such a combination implies a synergistic and opposite effect on the RAAS, in which the ACE inhibitor or the ARB antagonize the counter-regulatory system activity triggered by the diuretic, thus improving the efficacy and tolerability of single drug components [9–11].

Recently, we published four randomized, double-blind, parallel group, direct comparative studies (also called “Z” studies, because of the common initial of their acronyms: ZODIAC, ZENITH, ZAMES, and ZEUS) which were planned to gain a deeper insight into the mechanisms of the antihypertensive effects of a two-drug fixed combination between a RAAS antagonist and a thiazide diuretic [12–15]. In these non-inferiority trials, efficacy and safety of the sulfhydryl ACE inhibitor zofenopril and of the ARB irbesartan both combined with hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) 12.5 mg were tested in hypertensive patients with one or more CV risk factors beyond hypertension (including diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and advanced age) and not responding to a previous monotherapy. In all studies, zofenopril and irbesartan were started at a dose of 30 and 150 mg, respectively, and were increased during the course of the follow-up to 60 and 300 mg, in non-responders, in order to check the effectiveness and tolerability of a highest dose of the drugs. Efficacy was evaluated not only in the office but also over 24 h by ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM). In addition, ancillary or pleiotropic features of the study drugs were evaluated by studying their effect on inflammation, target organ damage, arterial stiffness, and metabolic biochemical parameters (blood glucose and lipids). A summary of the study designs and an overview of the number of patients included in each individual study and the main patient features are reported in Table 1. In total, 1535 hypertensives were recruited in 126 centers in six European countries (Italy, Greece, Lithuania, Romania, Turkey, and Russia). Both drugs had a similar efficacy on office and ambulatory BP but some differences between the study medications could be observed for secondary efficacy endpoints. In the ZODIAC study, treatment with the zofenopril combination was associated with a larger (p = 0.001) reduction of hs-CRP (−0.52 mg/dL) than irbesartan (+0.97 mg/dL, p = 0.001), suggesting a potential protective effect against vascular inflammation, a well-known promoter of atherosclerosis at all its stages, from the endothelial cell dysfunction to the culmination in acute coronary syndrome [16, 17]. In the ZENITH study, both treatments had a similar positive effect on regression of cardiac and renal damage, whereas a larger proportion of patients showing carotid plaque regression was observed under zofenopril (31.6% vs. 16.1%; p = 0.047), particularly in the subgroup of patients taking the low dose of zofenopril (30 mg) plus HCTZ 12.5 mg (4.7% vs 10.0% irbesartan 150 mg plus HCTZ 12.5 mg; p = 0.043). These findings further confirmed the potent antiatherosclerotic effects of RAAS blockade and in particular of zofenopril, which are mediated by its antihypertensive, anti-inflammatory, antiproliferative, and oxidative stress-lowering properties [18, 19]. In the ZAMES study, metabolic parameters and renal function were not altered by treatments, except for albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR), whose reduction with treatment was larger under irbesartan combined with the thiazide diuretics (−24.2 vs. −9.9 mg/g with zofenopril; p = 0.027). The metabolic neutrality of treatment documented in this large study is an important finding, given the relevant notion that thiazide diuretics may induce metabolic abnormalities and that patients with metabolic syndrome may be particularly susceptible to such effects [20]. Finally, in a subgroup of 93 elderly hypertensive patients of the ZEUS study, treatment with zofenopril or irbesartan was associated with small reductions in central SBP and arterial stiffness indices (pulse wave velocity or PWV and augmentation index or AI), which were similar between the two study drugs at any time point of the study, including the first 6 weeks when all patients were treated with the lowest dose of zofenopril or irbesartan combined with the thiazide diuretic. Though such improvements were not striking as a result of the limited vascular impairments of the patients, they are relevant, because arterial stiffness represents a late manifestation of increase elastic arterial stiffness [21], and because they are consistent with those observed in previous randomized studies with the same classes of antihypertensive agents [22–24].

Given these premises, in the next sections of this review we will briefly summarize and discuss other results of the “Z” studies, which were not presented in the original publications. These include outcomes based on low dose treatment of both study medications, pooled individual analysis of ABPM data and of safety data. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Efficacy in Low Dose Subgroup

As expected on the basis of the study design and objectives, most of the patients enrolled in the “Z” studies took the high dose of zofenopril (75%) and the high dose of irbesartan (69%).

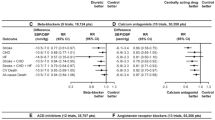

In three of the four “Z” studies, the efficacy of low dose zofenopril combination (30 mg) and low dose irbesartan combination (150 mg) was also assessed: this subanalysis was compelling because the zofenopril 30 mg plus HCTZ 12.5 mg combination is at present the only marketed fixed-drug combination of zofenopril with a thiazide diuretic. Average office BP changes with treatment under the low drug doses in these studies are shown in Fig. 1. No patients were under low dose drug treatment at study end in the ZAMES study because only patients forcedly up-titrated to the high dose were kept in that study.

Mean changes (Δ) with treatment (and 95% confidence interval) in office systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) in the ZODIAC (a) and ZENITH study (b), and mean daytime SBP changes in the ZEUS study (c), in the subgroup of patients receiving the low drug doses during the study. The p values refer to the statistical significance of the between-treatment difference

In the ZODIAC study at the end of the 18 weeks, office sitting DBP reductions were significantly larger (p = 0.022) with zofenopril 30 mg plus HCTZ [n = 55; 19.8 (22.8, 16.8) mmHg] than with irbesartan 150 mg plus HCTZ [n = 69; 14.5 (17.9, 11.1) mmHg], whereas they were similar for SBP [zofenopril: 25.8 (30.5, 21.2) mmHg vs. irbesartan: 22.0 (27.1, 16.8) mmHg; p = 0.274] [25]. In the patients of the ZENITH study taking the low drug doses at study end (n = 223), the proportion of responders did not differ (p = 0.693) between zofenopril (76.4%) and irbesartan (78.9%), as well as the office SBP and DBP reductions (Fig. 1) [13]. Also in the subgroup of patients with moderate–severe hypertension (office BP ≥160 mmHg and DBP ≥100 mmHg) taking the lowest dose during the study, the zofenopril combination was associated with an antihypertensive response similar to that of the irbesartan combination (88.9% vs. 80.0%; p = 0.596).

In the patients of the ZEUS study maintaining the low drug doses throughout the study (n = 77), the magnitude of the daytime BP lowering was always slightly larger under zofenopril 30 mg plus HCTZ 12.5 mg than under irbesartan 150 mg plus HCTZ 12.5 mg [14]. In this study subgroup, a statistically significant (p = 0.028) difference in favor of zofenopril-treated patients was achieved at study end [16.2 (20.0, 12.5) mmHg vs. 11.2 (14.4, 7.9) mmHg irbesartan-treated patients]. For the low dose subgroup also the percentage of patients showing daytime SBP normalization (<135 mmHg) and daytime SBP response (SBP <135 mmHg or reduction ≥10 mmHg) at study end was significantly larger under zofenopril (88.9% and 91.7%) than under irbesartan (73.2% and 78.0%; p = 0.017 and p = 0.024, respectively).

The high rate of BP control and the good BP-lowering effect observed in the “Z” studies with both RAAS antagonists at the lowest dosage confirm recommendations of current guidelines which indicate a two-drug low dose combination of an ACE inhibitor or an ARB and a thiazide diuretic as a reasonable alternative to high dose monotherapy in patients previously classified as non-responders to monotherapy [6, 7]. It also strengthens the evidence from previous large randomized studies in patients with mild–moderate hypertension, in which treatment with the low dose of zofenopril (30 mg) combined with HCTZ 12.5 mg once-daily showed a greater efficacy than the monotherapy with either agent, with an increase in the response rate up to 55–65% [26, 27].

Efficacy Over 24 h

As detailed in the publications of the individual “Z” studies, the good office BP control obtained with zofenopril and irbesartan was confirmed over 24 h by ABPM, which was available for 53% of patients included in primary endpoint analysis. In order to better assess the antihypertensive effect of the drugs over 24 h, we pooled individual ABPM data of the ZODIAC, ZENITH, and ZAMES studies, namely the “Z” studies with similar inclusion criteria (the ZEUS study included only isolated systolic hypertension or ISH patients, and selection of patients for study entry was based not only on office but also on ambulatory BP). In the 561 patients of the pooled ABPM data analysis, the 24-h antihypertensive effect was similar between the two drugs, regardless of the dose employed: 24-h SBP was reduced by 7.6 (9.5, 5.7) mmHg under zofenopril and by 9.5 (11.2, 7.7) mmHg under irbesartan (p = 0.155), whereas DBP dropped by 5.5 (6.6, 4.4) mmHg and by 6.6 (7.6, 5.5) mmHg (p = 0.170).

As shown in Fig. 2a, both drugs displayed a similarly smooth and long-lasting antihypertensive effect, with similar smoothness indices for SBP [zofenopril: 0.57 (0.41, 0.73) vs. irbesartan: 0.76 (0.61, 0.91); p = 0.100] and DBP [0.50 (0.36, 0.63) vs. 0.61 (0.49, 0.74); p = 0.217]. Interestingly, the magnitude of the 24-h BP reduction yielded by zofenopril and irbesartan in the “Z” studies was comparable with that observed in previous studies based on ABPM and making use of the same doses of the two drug combinations [28, 29].

Average hourly systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) values at baseline (B, dashed line) and at the end of the double-blind treatment (T, continuous line) in patients treated with zofenopril 30–60 mg plus hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) 12.5 mg or irbesartan 150–300 mg plus hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg in the whole 561 patients of the ZODIAC, ZENITH, and ZAMES studies (a) and in those treated with the lowest dose of zofenopril (30 mg) or irbesartan (150 mg) (b) and with a valid ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM)

The BP-lowering effect of the two tested drugs was also similar in the low (n = 157, 28% of patients) and the high drug dose (n = 404; 72%) subgroup, either over 24 h or in the last 6 h from the last drug intake: in this subperiod the BP reduction was still comparable between zofenopril and irbesartan and corresponded to 75–85% of the overall 24-h effect (Fig. 3).

24-h and last 6-h average systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) reductions (Δ) with treatment (and 95% confidence interval) in the 561 patients of the ZODIAC, ZENITH, and ZAMES studies with a valid ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM). Data are shown for the two subgroups receiving low or high dose treatment at study end

In the low drug dose subgroup BP was effectively reduced both under zofenopril (30 mg) and irbesartan (150 mg) plus HCTZ 12.5 mg for each hour of the 24 h (Fig. 2b). Twenty-four hour BP was also similarly reduced in subgroups of high risk patients such as males, aged persons (≥55 years for males and ≥65 years for females), smokers and alcohol drinkers, patients with diabetes or impaired fasting glucose, patients with a high or very high cardiovascular risk, and patients with sustained hypertension (namely those simultaneously displaying elevated office and 24-h BP) (Table 2).

Long-Term Efficacy of the Combinations

In the ZODIAC and ZENITH studies long-term follow-up of patients treated with high dose combination at study end was planned in order to collect more information on study drug efficacy and safety. Both drugs ensured a consistent efficacy, together with a good tolerability (see next section), also in the long-term follow-up observation.

In the ZODIAC study at the end of the 18 weeks of double-blind treatment, 229 patients among those receiving high dose combination treatment entered an open-label extension phase and were followed up for an additional 14 weeks. As shown in the upper panel of Fig. 4, both SBP and DBP reductions were well maintained during long-term treatment and did not differ between the two study arms.

Average office systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) (±SD) in the whole 32 weeks of the ZODIAC study, for patients treated with high dose zofenopril or irbesartan combination (a). Office and 24-h SBP and DBP reductions (Δ) in the 48 weeks of treatment (and 95% confidence interval) in the high dose subgroup of the ZENITH study are reported in b

In the 223 patients of the ZENITH study receiving drug dose up-titration at the end of the 18 weeks of treatment and continuing the double-blind treatment for additional 30 weeks, no difference was observed in office BP response between the two treatment groups (28.6% zofenopril vs. 22.1% irbesartan; p = 0.178) [13]. As shown in Fig. 4, in these patients, office and 24-h BPs were similarly reduced under zofenopril and irbesartan combinations either at the end of the 18 weeks or at the end of the extension phase. Likewise, the impact of treatment on organ damage did not significantly differ between the two study drugs.

Tolerability of Both Drug Combinations

The overall tolerability profile of zofenopril and irbesartan in the “Z” studies was good and comparable with that in previous reports [26, 30]. The safety population consisted of 1535 patients, of which 762 received the zofenopril and 773 the irbesartan combination (Table 3). Both drugs were well tolerated, with a very limited number of adverse events, which were well balanced between the two study arms (25.2% of patients receiving zofenopril and 21.9% receiving irbesartan; p = 0.715). The percentage of drug-related adverse events was much smaller than that of overall adverse events and still homogeneously distributed between the two groups (9.4% zofenopril vs. 6.2% irbesartan; p = 0.273). In total, only 66 patients (4.3%) were withdrawn from the studies because of an adverse event, 38 in the zofenopril (4.9%) and 28 in the irbesartan treatment group (3.6%; p = 0.593). The most common drug-related adverse event observed under zofenopril was cough (1.8% of patients), whereas dizziness was the most prevalent drug adverse reaction in irbesartan-treated patients (1.4%). All these side effects could be expected with these classes of drugs. Interestingly, the prevalence of cough with zofenopril in the “Z” studies (1.8%) was very close to that observed in previous double-blind or open-label post-marketing studies including 5794 hypertensive patients (2.4%) [31]. The relatively low incidence of cough in patients receiving zofenopril might be related to its limited ACE inhibitor potency at the lung level, responsible for a lesser accumulation of bradykinin and a reduced synthesis of prostaglandins in this tissue, as found in some experimental and animal studies [31].

In the ZODIAC and ZENITH studies safety was also evaluated during a long-term follow-up under high drug dose. In the ZODIAC study, 6.3% of zofenopril-treated patients and 1.9% of irbesartan-treated patients reported a drug-related adverse event (p = 0.172) during the prolonged follow-up. No patients treated with irbesartan were withdrawn from the study during the extension phase, whereas five patients (4.5%) dropped out in the zofenopril group (p = 0.060). In the extension phase of the ZENITH study, 12.3% of patients under high dose zofenopril plus HCTZ and 11.4% under high dose irbesartan plus HCTZ reported an adverse event (p = 0.843). Treatment-related adverse events occurred in 3.8% and 3.5% of patients under the two study drugs (p = 0.859); of these patients four were definitely withdrawn from the extension phase (three taking zofenopril vs. one taking irbesartan; p = 0.368) [13].

Limitations of This Review

A major limitation of this review is that it reports mixed information from previous original publications and from new pooled data or subgroup analyses, particularly those based on ABPM data. For this reason, it may be argued that it cannot be classified either as a review or an original paper. Indeed, in our review we briefly summarized the main results of the single studies, which helped introduce the reader to the secondary results which were available at the time of the original publications, but which were only outlined or even omitted for reasons of space. The current review gave us the possibility to add this information in order to provide a comprehensive presentation of all the available data of the “Z” studies. We think that this review may help complete the large amount of information deriving from the “Z” studies, which stand amongst the largest double-blind randomized studies comparing the effect of an ACE inhibitor and an ARB in hypertensive patients with multiple risk factors not controlled by a previous monotherapy.

Conclusions

In all the “Z” studies the combination between zofenopril and HCTZ was always similarly effective as that of irbesartan plus HCTZ, and it performed well either at the lowest dose (30 mg), which is the currently marketed one, or at the highest (60 mg) dose. Zofenopril also showed some ancillary features which suggest that the fixed combination of this drug with HCTZ may have a particular place in the treatment of high-risk or monotherapy-treated uncontrolled hypertensive patients requiring a more prompt, intensive, and sustained BP reduction, in line with the recommendations of current guidelines [6, 7]. The effective BP reduction and the large proportion of responders in both treatment arms in the “Z” studies also support the findings of previous studies that, in most patients not responding to a single antihypertensive medication, combination treatment with two drugs may substantially increase the chance of response [32, 33]. Vascular protection afforded by the sulfhydryl ACE inhibitor zofenopril may be related to its direct antiatherogenic effects [19, 34, 35], both reduction of systemic oxidative stress [17, 19, 34–38] and nitric oxide deficiency [17, 19, 38, 39], and enhancement of circulating endothelial progenitor cells [36] together with improved vascular function [40, 41].

In conclusion, results of the large “Z” studies confirm that combination treatment between a drug acting on the RAAS and a thiazide diuretic should be among the preferred choices when monotherapies fail to lower BP to or below target levels, particularly in patients displaying multiple CV risk factors.

References

Bakris G, Sarafidis P, Agarwal R, Ruilope L. Review of blood pressure control rates and outcomes. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2014;8:127–41.

Gorostidi M, de la Sierra A. Combination therapy in hypertension. Adv Ther. 2013;30:320–36.

Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Effects of blood pressure lowering on outcome incidence in hypertension: 3. Effects in patients at different levels of cardiovascular risk–overview and meta-analyses of randomized trials. J Hypertens. 2014;32:2305–14.

Collaboration Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration, Sundström J, Arima H, et al. Blood pressure-lowering treatment based on cardiovascular risk: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet. 2014;384:591–8.

Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts): Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23:NP1–NP96.

Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC practice guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Blood Press. 2014;23:3–16.

Weber MA, Schiffrin EL, White WB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension in the community: a statement by the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014;16:14–26.

Kjeldsen S, Feldman RD, Lisheng L, et al. Updated national and international hypertension guidelines: a review of current recommendations. Drugs. 2014;74:2033–51.

Mercier K, Smith H, Biederman J. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibition: overview of the therapeutic use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, and direct renin inhibitors. Prim Care. 2014;41:765–78.

Schmieder RE. The role of fixed-dose combination therapy with drugs that target the renin-angiotensin system in the hypertension paradigm. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2010;32:35–42.

Waeber B, Feihl F, Ruilope LM. Fixed-dose combinations as initial therapy for hypertension: a review of approved agents and a guide to patient selection. Drugs. 2009;69:1761–76.

Agabiti-Rosei E, Manolis A, Zava D, Omboni S, ZODIAC Study Group. Zofenopril plus hydrochlorothiazide and irbesartan plus hydrochlorothiazide in previously treated and uncontrolled diabetic and non-diabetic essential hypertensive patients. Adv Ther. 2014;31:217–33.

Malacco E, Omboni S, Parati G. Blood pressure response to zofenopril or irbesartan each combined with hydrochlorothiazide in high-risk hypertensives uncontrolled by monotherapy: a randomized, double-blind, controlled, parallel group, noninferiority trial. Int J Hypertens. 2015;2015:139465.

Modesti PA, Omboni S, Taddei S, et al. Zofenopril or irbesartan plus hydrochlorothiazide in elderly patients with isolated systolic hypertension untreated or uncontrolled by previous treatment: a double-blind, randomized study. J Hypertens. 2016;34:576–87.

Napoli C, Omboni S, Borghi C. Fixed-dose combination of zofenopril plus hydrochlorothiazide vs. irbesartan plus hydrochlorothiazide in hypertensive patients with established metabolic syndrome uncontrolled by previous monotherapy. The ZAMES study. J Hypertens. 2016;34:2287–97.

Devaraj S, Singh U, Jialal I. The evolving role of C-reactive protein in atherothrombosis. Clin Chem. 2009;55:229–38.

Napoli C, Sica V, de Nigris F, et al. Sulfhydryl angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition induces sustained reduction of systemic oxidative stress and improves the nitric oxide pathway in patients with essential hypertension. Am Heart J. 2004;148:e5.

Schmieder RE, Hilgers KF, Schlaich MP, Schmidt BM. Renin-angiotensin system and cardiovascular risk. Lancet. 2007;369:1208–19.

Napoli C, Bruzzese G, Ignarro LJ, et al. Long-term treatment with sulfhydryl angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition reduces carotid intima-media thickening and improves the nitric oxide/oxidative stress pathways in newly diagnosed patients with mild to moderate primary hypertension. Am Heart J. 2008;156(1154):e1–8.

Musini VM, Nazer M, Bassett K, Wright JM. Blood pressure-lowering efficacy of monotherapy with thiazide diuretics for primary hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(5):CD003824.

McEniery CM, Wilkinson IB, Avolio AP. Age, hypertension and arterial function. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;34:665–71.

Ong KT, Delerme S, Pannier B, et al. Aortic stiffness is reduced beyond blood pressure lowering by short-term and long-term antihypertensive treatment: a meta-analysis of individual data in 294 patients. J Hypertens. 2011;29:1034–42.

Manisty CH, Hughes AD. Meta-analysis of the comparative effects of different classes of antihypertensive agents on brachial and central systolic blood pressure, and augmentation index. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;75:79–92.

Omboni S. Do arterial stiffness and wave reflections improve more with angiotensin receptor blockers than with other antihypertensive drug classes? J Thorac Dis. 2016;8:1417–20.

Borghi C, Omboni S. Zofenopril plus hydrochlorothiazide combination in the treatment of hypertension: an update. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2014;12:1055–65.

Omboni S, Malacco E, Parati G. Zofenopril plus hydrochlorothiazide fixed combination in the treatment of hypertension and associated clinical conditions. Cardiovasc Ther. 2009;27:275–88.

Zanchetti A, Parati G, Malacco E. Zofenopril plus hydrochlorothiazide: combination therapy for the treatment of mild to moderate hypertension. Drugs. 2006;66:1107–15.

Parati G, Omboni S, Malacco E. Antihypertensive efficacy of zofenopril and hydrochlorothiazide combination on ambulatory blood pressure. Blood Press. 2006;15(suppl. 1):7–17.

Neutel JM, Smith D. Ambulatory blood pressure comparison of the anti-hypertensive efficacy of fixed combinations of irbesartan/hydrochlorothiazide and losartan/hydrochlorothiazide in patients with mild-to-moderate hypertension. J Int Med Res. 2005;33:620–31.

Bramlage P. Fixed combination of irbesartan and hydrochlorothiazide in the management of hypertension. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2009;5:213–24.

Omboni S, Borghi C. Zofenopril and incidence of cough: a review of published and unpublished data. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2011;7:459–71.

Wald DS, Law M, Morris JK, Bestwick JP, Wald NJ. Combination therapy versus monotherapy in reducing blood pressure: meta-analysis on 11,000 participants from 42 trials. Am J Med. 2009;122:290–300.

Law MR, Wald NJ, Morris JK, Jordan RE. Value of low dose combination treatment with blood pressure lowering drugs: analysis of 354 randomised trials. BMJ. 2003;326:1427.

Napoli C, Cicala C, D’Armiento FP, et al. Beneficial effects of ACE-inhibition with zofenopril on plaque formation and low-density lipoprotein oxidation in watanabe heritable hyperlipidemic rabbits. Gen Pharmacol. 1999;33:467–77.

de Nigris F, D’Armiento FP, Somma P, et al. Chronic treatment with sulfhydryl angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors reduce susceptibility of plasma LDL to in vitro oxidation, formation of oxidation-specific epitopes in the arterial wall, and atherogenesis in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Int J Cardiol. 2001;81:107–15.

Cacciatore F, Bruzzese G, Vitale DF, et al. Effects of ACE inhibition on circulating endothelial progenitor cells, vascular damage, and oxidative stress in hypertensive patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;67:877–83.

Sacco G, Mario B, Lopez G, Evangelista S, Manzini S, Maggi CA. ACE inhibition and protection from doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in the rat. Vascul Pharmacol. 2009;50:166–70.

Scribner AW, Loscalzo J, Napoli C. The effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition on endothelial function and oxidant stress. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;482:95–9.

García-Estañ J, Ortiz MC, O’Valle F, et al. Effects of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors in combination with diuretics on blood pressure and renal injury in nitric oxide-deficiency-induced hypertension in rats. Clin Sci (Lond). 2006;110:227–33.

Elijovich F, Laffer CL, Schiffrin EL. The effects of atenolol and zofenopril on plasma atrial natriuretic peptide are due to their interactions with target organ damage of essential hypertensive patients. J Hum Hypertens. 1997;11:313–9.

Pasini AF, Garbin U, Nava MC, et al. Effect of sulfhydryl and non-sulfhydryl angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on endothelial function in essential hypertensive patients. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20:443–50.

Acknowledgements

The “Z” studies were financially supported by Menarini International Operations Luxembourg S.A., through an unconditional and unrestricted grant. Article processing charges and open access fee for the present paper were funded by Menarini International Operations Luxembourg S.A. Concerning the current review paper, the funding source did not influence or comment on planned methods, protocol, data analysis, and interpretation of the results, preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published.

Disclosures

Stefano Omboni has received honorarium from Menarini International for manuscript preparation. Ettore Malacco has occasionally received grants for lectures or for scientific meeting attendance from Menarini International. Claudio Napoli has occasionally received grants for lectures or for scientific meeting attendance from Menarini International. Pietro Amedeo Modesti has occasionally received grants for lectures or for scientific meeting attendance from Menarini International. Athanasios Manolis has occasionally received grants for lectures or for scientific meeting attendance from Menarini International. Gianfranco Parati has occasionally received grants for lectures or for scientific meeting attendance from Menarini International. Enrico Agabiti-Rosei has occasionally received grants for lectures or for scientific meeting attendance from Menarini International. Claudio Borghi has occasionally received grants for lectures or for scientific meeting attendance from Menarini International.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because they are property of the sponsor of the studies, Menarini International Operations Luxembourg S.A., but they are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/8097F06066FC0C29.

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12325-017-0537-4.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Omboni, S., Malacco, E., Napoli, C. et al. Efficacy of Zofenopril vs. Irbesartan in Combination with a Thiazide Diuretic in Hypertensive Patients with Multiple Risk Factors not Controlled by a Previous Monotherapy: A Review of the Double-Blind, Randomized “Z” Studies. Adv Ther 34, 784–798 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-017-0497-8

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-017-0497-8