Abstract

Background

Women with young children (<5 years) are an important group for physical activity intervention.

Purpose

The objective of the study was to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of MobileMums—a physical activity intervention for women with young children.

Methods

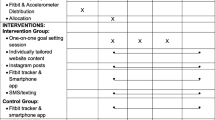

Women were randomized to MobileMums (n = 133) or a control group (n = 130). MobileMums was delivered primarily via individually tailored text messages. Moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) was measured by self-report and an accelerometer at baseline, end of the intervention (13 weeks), and 6 months later (9 months). Changes were analyzed using repeated-measures models.

Results

MobileMums was feasible to deliver and acceptable to women. Self-reported MVPA duration (minutes/week) and frequency (days/week) increased significantly post-intervention (13-week intervention effect 48.5 min/week, 95 % credible interval (CI) [13.4, 82.9] and 1.6 days/week, 95 % CI [0.6, 2.6]). Intervention effects were not maintained 6 months later. No effects were observed in accelerometer-derived MVPA.

Conclusions

MobileMums increased women’s self-reported MVPA immediately post-intervention. Future investigations need to target sustained physical activity improvements (ACTRN12611000481976).

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Brown W, Mishra G, Lee C, Bauman A. Leisure time physical activity in Australian women: relationship with well being and symptoms. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2000; 71: 206-216.

Adamo KB, Langlois KA, Brett KE, Colley RC. Young children and parental physical activity levels: findings from the Canadian health measures survey. Am J Prev Med. 2012; 43: 168-175.

Berge JM, Larson N, Bauer KW, Neumark-Sztainer D. Are parents of young children practicing healthy nutrition and physical activity behaviors? Pediatrics. 2011; 127: 881-887.

Bellows-Riecken KH, Rhodes RE. A birth of inactivity? A review of physical activity and parenthood. Prev Med. 2008; 46: 99-110.

Brown W, Trost S. Life transitions and changing physical activity patterns in young women. Am J Prev Med. 2003; 25: 140-143.

Brown WJ, Burton NW, Rowan PJ. Updating evidence on physical activity and health in women. Am J Prev Med. 2007; 33: 404-411.

Nomaguchi KM, Bianchi SM. Exercise time: gender differences in the effects of marriage, parenthood, and employment. J Marriage Fam. 2004; 66: 413-430.

Haskell WL, Blair SN, Hill JO. Physical activity: health outcomes and importance for public health policy. Prev Med. 2009; 49: 280-282.

Teychenne M, York R. Physical activity, sedentary behavior, and postnatal depressive symptoms: a review. Am J Prev Med. 2013; 45: 217-227.

van der Plight P, Willcox J, Hesketh KD, et al. Systematic review of lifestyle interventions to limit postpartum weight retention: implications for future opportunities to prevent maternal overweight and obesity following childbirth. Obes Rev. 2013; 14: 792-805.

Choi J, Fukuoka Y, Lee JH. The effects of physical activity and physical activity plus diet interventions on body weight in overweight or obese women who are pregnant or in postpartum: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Prev Med. 2013; 56: 351-364.

Gilinsky AS, Dale H, Robinson C, Hughes A, McInnes R, Lavellee D. Efficacy of physical activity interventions in post-natal content coding of behaviour change techniques [published populations: systematic review, meta-analysis and online ahead of print April 02 2014]. Health Psychol Rev. 2014

Cramp A, Brawley L. Moms in motion: a group-mediated cognitive-behavioural physical activity intervention. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2006; 3: 1-9.

Clarke KK, Freeland-Graves J, Klohe-Lehman DM, Milani TJ, Nuss HJ, Lafrey S. Promotion of physical activity in low-income mothers using pedometers. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007; 107: 962-967.

Watson N, Milat AJ, Thomas M, Currie J. The feasibility and effectiveness of pram walking groups for postpartum women in western Sydney. Health Promot J Austr. 2005; 16: 93-99.

Armstrong K, Edwards H. The effectiveness of a pram-walking exercise programme in reducing depressive symptomatology for postnatal women. Int J Nurs Pract. 2004; 10: 177-194.

Monteiro SMDR, Jancey J, Dhaliwal SS, et al. Results of a randomized controlled trial to promote physical activity behaviours in mothers with young children. Prev Med. 2014; 59: 12-18.

Daley AJ, Winter H, Grimmett C, McGuinness M, McManus R, MacArthur C. Feasibility of an exercise intervention for women with postnatal depression: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Prac. 2008; 58: 178-183.

Fahrenwald NL, Atwood JR, Walker SN, Johnson DR, Berg K. A randomized pilot test of “Moms on the Move” a physical activity intervention for WIC Mothers. Ann Behav Med. 2004; 27: 82-90.

Armstrong K, Edwards H. The effects of exercise and social support on mothers reporting depressive symptoms: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2003; 12: 130-138.

Currie J. Pramwalking as postnatal exercise and support: an evaluation of the stroll Your Way to Well-Being Program and supporting resources in terms of individual participation rates and community group formation. Aust J Midwifery. 2001; 14: 21-25.

Rowley C, Dixon L, Palk R. Promoting physical activity: walking programmes for mothers and children. Community Pract. 2007; 80: 28-32.

Albright CL, Maddock JE, Nigg CR. Increasing physical activity in postpartum multiethnic women in Hawaii: results from a pilot study. BMC Womens Health. 2009; 9(4).

Reinhardt JA, Van Der Ploeg HP, Grzegrzulka R, Timperley JG. lmplementing lifestyle change through phone-based motivational interviewing in rural-based women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus. Health Promot J Austr. 2012; 23: 5-9.

Lewis BA, Martinson BC, Sherwood NE, Avery MD. A pilot study evaluating a telephone-based exercise intervention for pregnant and postpartum women. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2011; 56: 127-131.

Fjeldsoe BS, Marshall AL, Miller YD. Behavior change interventions delivered by mobile telephone short-message service. Am J Prev Med. 2009; 36: 165-173.

Fjeldsoe BS, Miller YD, O’Brien JL, Marshall AL. Iterative development of MobileMums: a physical activity intervention for women with young children. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012; 9(151)

Fjeldsoe BS, Miller YD, Marshall AL. MobileMums: a randomized controlled trial of an SMS-based physical activity intervention. Ann Behav Med. 2010; 39: 101-111.

Marshall AL, Miller YD, Graves N, Barnett AG, Fjeldsoe BS. Moving MobileMums forward: protocol for a larger randomized controlled trial of an improved physical activity program for women with young children. BMC Public Health. 2013; 13(593).

Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, et al. Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. The CONSORT statement. JAMA. 1996; 276: 637-639.

Miller YD, Thompson R, Porter J, Armanasco A, Prosser S. The Having a Baby in Queensland Survey, 2010. Brisbane, Australia: The University of Queensland; 2010.

Artal R, O’Toole M. Guidelines of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists for exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Br J Sports Med. 2003; 37: 6-12.

Fjeldsoe BS, Marshall AL, Miller YD. Measurement properties of the Australian Women’s Activity Survey. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009; 41: 1020-1033.

Department of Health and Ageing. National physical activity guidelines for adults. Canberra: Australian Government; 2005.

Winkler EA, Gardiner PA, Clark BK, Matthews CE, Owen N, Healy GN. Identifying sedentary time using automated estimates of accelerometer wear time. Br J Sports Med. 2012; 46: 436-442.

Swartz AM, Strath SJ, Bassett DR, O’Brian WL, King GA, Ainsworth BE. Estimation of energy expenditure using CSA accelerometers at hip and wrist sites. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000; 32: S450-S456.

Brown W, Ringuet C, Trost S, Jenkins D. Measurement of energy expenditure of daily tasks among mothers of young children. J Sci Med Sport. 2001; 4: 379-385.

Haskell W, Lee I, Pate R, et al. Physical activity and public health: Updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Foundation. Circulation. 2007; 116: 1081-1093.

Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Msse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008; 40: 181-188.

Department of Health and Ageing. National Physical Activity Guidelines for Australian Adults. Canberra: Australian Government; 2005.

Barnett AG, van der Pols JC, Dobson AJ. Regression to the mean: what it is and how to deal with it. Int J Epidemiol. 2005; 34: 215-220.

Deddens JA, Petersen MR. Approaches for estimating prevalence ratios. Occup Environ Med. 2008; 65: 501-506.

Bland JM, Altman DG. Bayesians and frequentists. BMJ. 1998; 317: 1151-1160.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2013.

Plummer M. JABS Version 3.3.0 User Manual. 2012.

Fjeldsoe BS, Neuhaus M, Winkler E, Eakin E. Systematic review of maintenance of behavior change following physical activity and dietary interventions. Health Psychol. 2011; 30: 99-109.

Waters LA, Galichet B, Owen N, Eakin E. Who participates in physical activity intervention trials. J Phys Act Health. 2011; 8: 85-103.

Middleton KM, Patidar SM, Perri MG. The impact of extended care on the long-term maintenance of weight loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2012; 13: 509-517.

Donaldson EL, Fallows S, Morris M. A text message based weight management intervention for overweight adults. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2014; 27: 90-97.

Winkler E, Waters L, Eakin E, Fjeldsoe B, Owen N, Reeves M. Is measurement error altered by participation in a physical activity intervention? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013; 45: 1004-1011.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the women of Caboolture who participated in the study. We would also like to thank project staff for their integrity and commitment, Jasmine O’Brien, Sarah Mair, Jacqueline Watts, Joy Nicols, and Kylie Heenan. Thanks also to the Queensland Centre for Mothers & Babies at The University of Queensland who assisted us by inviting women on their research database to participate in this trial. This study was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council project grant no 614,244. The last author was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Career Development Award no 553,000. Computational resources and services used in this work were provided by the High Performance Computer and Research Support Unit, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia.

Author Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards

Authors Fjeldsoe, Miller, Barnett, Graves and Marshall declare that they have no conflict of interest. All procedures, including the informed consent process, were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Fjeldsoe, B.S., Miller, Y.D., Graves, N. et al. Randomized Controlled Trial of an Improved Version of MobileMums, an Intervention for Increasing Physical Activity in Women with Young Children. ann. behav. med. 49, 487–499 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-014-9675-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-014-9675-y