Abstract

Background

Sexual minorities have documented elevated risk factors that can lead to inflammation and poor immune functioning.

Purpose

This study aims to investigate disparities in C-reactive protein (CRP) and Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) by gender and sexual orientation.

Methods

We used the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health to examine disparities in CRP (N = 11,462) and EBV (N = 11,812).

Results

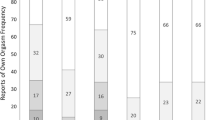

Among heterosexuals, women had higher levels of CRP and EBV than men. However, sexual minority men had higher levels of CRP and EBV than heterosexual men and sexual minority women. Lesbians had lower levels of CRP than heterosexual women.

Conclusions

Gender differences in CRP and EBV found between men and women who identify as 100 % heterosexual were reversed among sexual minorities and not explained by known risk factors (e.g., victimization, alcohol and tobacco use, and body mass index). More nuanced approaches to addressing gender differences in sexual orientation health disparities that include measures of gender nonconformity and minority stress are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Bartkiewicz MJ, Boesen MJ, Palmer NA. The 2011 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender Youth in Our Nation’s Schools. 2012. Available at http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/recordDetail?accno=ED535177. Accessed April 10, 2013.

Herek GM. Hate crimes and stigma-related experiences among sexual minority adults in the United States. J Interpers Violence. 2009; 24: 54-74.

Huebner DM, Rebchook GM, Kegeles SM. Experiences of harassment, discrimination, and physical violence among young gay and bisexual men. Am J Public Health. 2004; 94: 1200-1203.

Hatzenbuehler ML. The social environment and suicide attempts in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Pediatrics. 2011; 127: 896-903.

Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. The impact of institutional discrimination on psychiatric disorders in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: A prospective study. Am J Public Health. 2010; 100: 452-459.

Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003; 129: 674-697.

Meyer IH. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. J Health Soc Behav. 1995; 36: 38-56.

Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim H-J, Barkan SE, Muraco A, Hoy-Ellis CP. Health disparities among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults: Results from a population-based study. Am J Public Health. 2013; 103: 1802-1809.

Conron K, Mimiaga M, Landers S. A population-based study of sexual orientation identity and gender differences in adult health. Am J Public Health. 2010; 100: 1953-1960.

Cochran SD, Mays VM. Physical health complaints among lesbians, gay men, and bisexual and homosexually experienced heterosexual individuals: Results from the California Quality of Life Survey. Am J Public Health. 2007; 97: 2048-2055.

Everett B, Mollborn S. Differences in hypertension by sexual orientation among U.S. young adults. J Commun Health. 2013; 38: 588-596.

Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Slopen N. Sexual orientation disparities in cardiovascular biomarkers among young adults. Am J Prev Med. 2013; 44: 612-621.

Segerstrom SC, Miller GE. Psychological stress and the human immune system: A meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychol Bull. 2004; 130: 601-630.

McEwen BS. Stress, adaptation, and disease: Allostasis and allostatic load. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1998; 840: 33-44.

Shames RS. Gender differences in the development and function of the immune system. J Adolescent Health. 2002; 30: 59-70.

McClelland EE, Smith JM. Gender specific differences in the immune response to infection. Arch Immunol Ther Ex. 2011; 59: 203-213.

Cartier A, Côté M, Lemieux I, et al. Sex differences in inflammatory markers: what is the contribution of visceral adiposity? Am J Clin Nutr. 2009; 89: 1307-1314.

Casimir GJA, Duchateau J. Gender differences in inflammatory processes could explain poorer prognosis for males. J Clin Microbiol. 2011; 49(1): 478-479.

Cannon JG, St. Pierre BA. Gender differences in host defense mechanisms. J Psychiat Res. 1997; 31(1): 99-113.

Bailey JM, Zucker KJ. Childhood sex-typed behavior and sexual orientation: A conceptual analysis and quantitative review. Dev Psychol. 1995; 31: 43-55.

Zucker KJ. Reflections on the relation between sex-typed behavior in childhood and sexual orientation in adulthood. J Gay Lesbian Mental Health. 2008; 12(1–2): 29-59.

Lippa RA. Sexual orientation and personality. Ann Rev Sex Res. 2005; 16(1): 119-153.

Glaser R, Pearson GR, Jones JF, et al. Stress-related activation of Epstein–Barr virus. Brain Behav Immun. 1991; 5: 219-232.

Owen N, Poulton T, Hay FC, Mohamed-Ali V, Steptoe A. Socioeconomic status, C-reactive protein, immune factors, and responses to acute mental stress. Brain Behav Immun. 17(4): 286–295.

Tracy RP, Psaty BM, Macy E, et al. Lifetime smoking exposure affects the association of C-reactive protein with cardiovascular disease risk factors and subclinical disease in healthy elderly subjects. Arterioscl Throm Vas. 1997; 17: 2167-2176.

Danese A, McEwen BS. Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiol Behav. 2012; 106: 29-39.

Ridker PM. C-reactive protein, metabolic syndrome, and risk of incident cardiovascular events: An 8-year follow-up of 14,719 initially healthy American women. Circulation. 2003; 107: 391-397.

Yeun JY, Levine RA, Mantadilok V, Kaysen GA. C-reactive protein predicts all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000; 3: 469-476.

Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E, Lowe G, et al. C-reactive protein concentration and risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and mortality: An individual participant meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010; 375: 132.

Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, et al. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease application to clinical and public health practice: A statement for healthcare professionals from the centers for disease control and prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2003; 107: 499-511.

Cohen S, Herbert TB. Health psychology: Psychological factors and physical disease from the perspective of human psychoneuroimmunology. Annu Rev Psychol. 1996; 47: 113-142.

Alho H, Sillanaukee P, Kalela A, Jaakkola O, Laine S, Nikkari ST. Alcohol misuse increases serum antibodies to oxidized LDL and C-reactive protein. Alcohol Alcoholism. 2004; 39: 312-315.

Bertran N, Camps J, Fernandez-Ballart J, et al. Diet and lifestyle are associated with serum C-reactive protein concentrations in a population-based study. J Lab Clin Med. 2005; 145: 41-46.

Gentile M, Panico S, Rubba F, et al. Obesity, overweight, and weight gain over adult life are main determinants of elevated HS-CRP in a cohort of Mediterranean women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010; 64: 873-878.

Stämpfli MR, Anderson GP. How cigarette smoke skews immune responses to promote infection, lung disease and cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009; 9: 377-384.

Harris TB, Ferrucci L, Tracy RP, et al. Associations of elevated interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein levels with mortality in the elderly. Am J Med. 1999; 106: 506-512.

Greenberg AS, Obin MS. Obesity and the role of adipose tissue in inflammation and metabolism. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006; 83: 461S-465S.

Slopen N, Kubzansky LD, McLaughlin KA, Koenen KC. Childhood adversity and inflammatory processes in youth: A prospective study. Psychoneuroendocrino. 2013; 38: 188-200.

Glaser R, Pearl DK, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Malarkey WB. Plasma cortisol levels and reactivation of latent Epstein–Barr virus in response to examination stress. Psychoneuroendocrino. 1994; 19: 765-772.

Glaser R, Padgett DA, Litsky ML, et al. Stress-associated changes in the steady-state expression of latent Epstein–Barr virus: Implications for chronic fatigue syndrome and cancer. Brain Behav Immun. 2005; 19: 91-103.

Jones JF, Straus SE. Chronic Epstein–Barr virus infection. Annu Rev Med. 1987; 38: 195-209.

Thompson MP, Kurzrock R. Epstein–Barr virus and cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004; 10: 803-821.

Godbout JP, Glaser R. Stress-induced immune dysregulation: Implications for wound healing, infectious disease and cancer. J Neuroimmune Pharm. 2006; 1: 421-427.

Ascherio A, Munch M. Epstein–Barr virus and multiple sclerosis. Epidemiology. 2000; 11: 220-224.

Ascherio A, Munger KL, Lennette ET, et al. Epstein–Barr virus antibodies and risk of multiple sclerosis. JAMA-J Am Med Assoc. 2001; 286: 3083-3088.

Hiles SA, Baker AL, de Malmanche T, Attia J. Interleukin-6, C-reactive protein and interleukin-10 after antidepressant treatment in people with depression: A meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2012; 42: 2015-2026.

Dube SR, Fairweather D, Pearson WS, Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Croft JB. Cumulative childhood stress and autoimmune diseases in adults. Psychosom Med. 2009; 71: 243-250.

Copeland WE, Shanahan L, Worthman C, Angold A, Costello EJ. Cumulative depression episodes predict later C-reactive protein levels: A prospective analysis. Biolo Psychiat. 2012; 71: 15-21.

Lee JGL, Blosnich JR, Melvin CL. Up in smoke: Vanishing evidence of tobacco disparities in the Institute of Medicine’s report on sexual and gender minority health. Am J Public Health. 2012; 102: 1-3.

Hughes T. Alcohol use and alcohol-related problems among sexual minority women. Alcoholism Treat Quart. 2011; 29: 403-435.

McCabe SE, Hughes TL, Bostwick WB, West BT, Boyd CJ. Sexual orientation, substance use behaviors and substance dependence in the United States. Addiction. 2009; 104: 1333-1345.

French SA, Story M, Remafedi G, Resnick MD, Blum RW. Sexual orientation and prevalence of body dissatisfaction and eating disordered behaviors: A population-based study of adolescents. Int J Eat Disorder. 1996; 19: 119-126.

Austin SB, Nelson LA, Birkett MA, Calzo JP, Everett B. Eating disorder symptoms and obesity at the intersections of gender, ethnicity, and sexual orientation in US high school students. Am J Public Health. 2013; 2: e16-e22.

Boehmer U, Bowen DJ, Bauer GR. Overweight and obesity in sexual-minority women: Evidence from population-based data. Am J Public Health. 2007; 97: 1134-1140.

Lakoski SG, Cushman M, Criqui M, et al. Gender and C-reactive protein: Data from the Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) cohort. Am Heart J. 2006; 152: 593-598.

Khera A, McGuire DK, Murphy SA, et al. Race and gender differences in C-reactive protein levels. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005; 46: 464-469.

Saltevo J, Vanhala M, Kautiainen H, Kumpusalo E, Laakso M. Gender differences in C-reactive protein, interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and adiponectin levels in the metabolic syndrome: A population-based study. Diabetic Med. 2008; 25: 747-750.

Valentine RJ, McAuley E, Vieira VJ, et al. Sex differences in the relationship between obesity, C-reactive protein, physical activity, depression, sleep quality and fatigue in older adults. Brain Behav Immun. 2009; 23: 643-648.

Wang TN, Lin MC, Wu CC, et al. Role of gender disparity of circulating high-sensitivity C-reactive protein concentrations and obesity on asthma in Taiwan. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011; 41: 72-77.

Ishii S, Karlamangla AS, Bote M, et al. Gender, obesity and repeated elevation of C-reactive protein: Data from the CARDIA cohort. PLoS ONE. 2012; 7(4): e36062.

McDade TW, Stallings JF, Angold A, et al. Epstein–Barr virus antibodies in whole blood spots: A minimally invasive method for assessing an aspect of cell-mediated immunity. Psychosom Med. 2000; 62: 560-568.

Villacres MC, Longmate J, Auge C, Diamond DJ. Predominant type 1 CMV-Specific memory T-helper response in humans: Evidence for gender differences in cytokine secretion. Hum Immunol. 2004; 65: 476-485.

Green MS, Cohen D, Slepon R, Robin G, Wiener M. Ethnic and gender differences in the prevalence of anti-cytomegalovirus antibodies among young adults in Israel. Int J Epidemiol. 1993; 22: 720-723.

Skouby SO, Gram J, Andersen LF, Sidelmann J, Petersen KR, Jespersen J. Hormone replacement therapy: Estrogen and progestin effects on plasma C-reactive protein concentrations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002; 186: 969-977.

Cushman M. Effects of hormone replacement therapy and estrogen receptor modulators on markers of inflammation and coagulation. Am J Cardiol. 2002; 90: F7-F10.

Yudkin JS, Stehouwer C, Emeis J, Coppack S. C-reactive protein in healthy subjects: Associations with obesity, insulin resistance, and endothelial dysfunction: A potential role for cytokines originating from adipose tissue? Arterioscl Throm Vas. 1999; 19: 972-978.

Hewitt PL, Flett GL, Mosher SW. The perceived stress scale: Factor structure and relation to depression symptoms in a psychiatric sample. J Psychopath Behav. 1992; 14: 247-257.

Ge X, Conger RD, Elder GH. Pubertal transition, stressful life events, and the emergence of gender differences in adolescent depressive symptoms. Dev Psychol. 2001; 37: 404-416.

Hyde JS, Mezulis AH, Abramson LY. The ABCs of depression: Integrating affective, biological, and cognitive models to explain the emergence of the gender difference in depression. Psychol Rev. 2008; 115: 291-313.

Rudolph KD, Hammen C. Age and gender as determinants of stress exposure, generation, and reactions in youngsters: A transactional perspective. Child Dev. 1999; 70: 660-677.

Piko B. Gender differences and similarities in adolescents’ ways of coping. Psychol Rec. 2011; 51: 223-235.

Leadbeater BJ, Kuperminc GP, Blatt SJ, Hertzog C. A multivariate model of gender differences in adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems. Dev Psychol. 1999; 35: 1268-1282.

Tamres LK, Janicki D, Helgeson VS. Sex differences in coping behavior: A meta-analytic review and an examination of relative coping. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2002; 6: 2-30.

Nolen-Hoeksema S. Emotion regulation and psychopathology: The role of gender. Ann Rev Clin Psycho. 2012; 8: 161-187.

Nolen-Hoeksema S, Aldao A. Gender and age differences in emotion regulation strategies and their relationship to depressive symptoms. Pers Indiv Differ. 2011; 51: 704-708.

Danner M, Kasl SV, Abramson JL, Vaccarino V. Association between depression and elevated C-reactive protein. Psychosom Med. 2003; 65: 347-356.

Howren MB, Lamkin DM, Suls J. Associations of depression with C-reactive protein, IL-1, and IL-6: A meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2009; 71: 171-186.

Ford DE, Erlinger TP. Depression and C-reactive protein in US adults: Data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2004; 164: 1010-1014.

D’augelli AR, Grossman AH, Starks MT. Gender atypicality and sexual orientation development among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. J Gay Lesbian Mental Health. 2008; 12: 121-143.

Rieger G, Linsenmeier JAW, Gygax L, Bailey JM. Sexual orientation and childhood sex atypicality: Evidence from home movies. Dev Psychol. 2006; 44: 46-58.

Lippa RA. Sex Differences and sexual orientation differences in personality: Findings from the BBC internet survey. Arch Sex Behav. 2008; 37: 173-187.

Everett BG, Mollborn S. Examining sexual orientation disparities in unmet medical needs among men and women. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2013: e1–25.

Carver CS, Connor-Smith J. Personality and coping. Annu Rev Psychol. 2010; 61: 679-704.

Rosario M, Hunter J, Gwadz M. Exploration of substance use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth prevalence and correlates. J Adolescent Res. 1997; 12: 454-476.

Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, et al. Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: A meta-analysis and methodological review. Addiction. 2008; 103: 546-556.

Austin SB, Ziyadeh NJ, Corliss HL, et al. Sexual orientation disparities in purging and binge eating from early to late adolescence. J Adolescent Health. 2009; 45: 238-245.

Juster R-P, Smith NG, Ouellet É, Sindi S, Lupien SJ. Sexual orientation and disclosure in relation to psychiatric symptoms, diurnal cortisol, and allostatic load. Psychosom Med. 2013; 75: 103-116.

Bearman PS, Jones J, Udry JR. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Research Design. Available at http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.html. Accessed September 1, 2013.

Ockene IS, Matthews CE, Rifai N, Ridker PM, Reed G, Stanek E. Variability and classification accuracy of serial high-sensitivity C-reactive protein measurements in healthy adults. Clin Chem. 2001; 47: 444-450.

Taylor SE, Lehman BJ, Kiefe CI, Seeman TE. Relationship of early life stress and psychological functioning to adult C-reactive protein in the coronary artery risk development in young adults study. Biol Psychiat. 2006; 60: 819-824.

Dowd JB, Palermo T, Brite J, McDade TW, Aiello A. Seroprevalence of Epstein–Barr virus infection in US children ages 6–19, 2003–2010. PLoS One. 2013; 8: e64921.

McDade TW, Burhop J, Dohnal J. High-sensitivity enzyme immunoassay for C-reactive protein in dried blood spots. Clin Chem. 2004; 50: 652-654.

Katz-Wise SL, Hyde JS. Victimization experiences of lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals: A meta-analysis. J Sex Res. 2012; 49: 142-167.

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983; 24: 385-396.

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Apl Psych Meas. 1977; 1: 385-401.

World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO Consultation. WHO Technical Report Series no. 894. WHO: Geneva. 2000.

Wallien MSC, Veenstra R, Kreukels BPC, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Peer group status of gender dysphoric children: A sociometric study. Arch Sex Behav. 2010; 39: 553-560.

Skidmore WC, Linsenmeier JA, Bailey JM. Gender nonconformity and psychological distress in lesbians and gay men. Arch Sex Behav. 2006; 35: 685-697.

Roberts AL, Rosario M, Slopen N, Calzo JP, Austin SB. Childhood gender nonconformity, bullying victimization, and depressive symptoms across adolescence and early adulthood: An 11-year longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Psy. 2013; 52: 143-152.

Roberts AL, Rosario M, Corliss HL, Koenen KC, Austin SB. Elevated risk of posttraumatic stress in sexual minority youths: Mediation by childhood abuse and gender nonconformity. Am J Public Health. 2012; 102: 1587-1593.

Roberts AL, Rosario M, Corliss HL, Koenen KC, Austin SB. Childhood gender nonconformity: A risk indicator for childhood abuse and posttraumatic stress in youth. Pediatrics. 2012; 129: 410-417.

Impett EA, Sorsoli L, Schooler D, Henson JM, Tolman DL. Girls’ relationship authenticity and self-esteem across adolescence. Dev Psychol. 2008; 44: 722-732.

Thornton B, Leo R. Gender typing, importance of multiple roles, and mental health consequences for women. Sex Roles. 1992; 27: 307-317.

Wong PT, Kettlewell G, Sproule CF. On the importance of being masculine: Sex role, attribution, and women’s career achievement. Sex Roles. 1985; 12: 757-769.

Rosario M, Scrimshaw E. Theories and Etiologies of Sexual Orientation. In: APA Handbook of Sexuality and Psychology: Vol 1. Person-based approaches. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association

Pearcey SM, Docherty KJ, Dabbs JM Jr. Testosterone and sex role identification in lesbian couples. Physiol Behav. 1996; 60: 1033-1035.

Cunningham TJ, Seeman TE, Kawachi I, et al. Racial/ethnic and gender differences in the association between self-reported experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination and inflammation in the CARDIA cohort of 4 US communities. Soc Sci Med. 2012; 75: 922-931.

Ford JL, Stowe RP. Racial–ethnic differences in Epstein–Barr virus antibody titers among U.S. children and adolescents. Ann Epidemiol. 2013; 23: 275-280.

Karlamangla AS, Merkin SS, Crimmins EM, Seeman TE. Socioeconomic and ethnic disparities in cardiovascular risk in the United States, 2001–2006. Ann Epidemiol. 2010; 20: 617-628.

Aknowledgements

This study is supported by NICHD grant R03 HD062597 and by the Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH), NICHD grant K12HD055892, and by the University of Colorado Population Center (grant R24 HD066613) through administrative and computing support. SB Austin is supported by NICHD grant R01 HD066963 and Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration, training grants MC00001 and Leadership Education in Adolescent Health Project 6T71-MC00009. K McLaughlin is supported by NIH grant K01-MH092526. The authors thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful and helpful comments. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the CDC, or any agencies involved in collecting the data.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Everett, B.G., Rosario, M., McLaughlin, K.A. et al. Sexual Orientation and Gender Differences in Markers of Inflammation and Immune Functioning. ann. behav. med. 47, 57–70 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9567-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9567-6