Abstract

Maternal mortality in South Africa is unacceptably high, and interventions to address this are urgently needed. Whilst urban centres, such as Johannesburg, are home to significant numbers of non-national migrant women, little is known about their maternal healthcare experiences. In order to inform future research, an exploratory study investigating the maternal healthcare and help-seeking experiences of migrant women living in inner-city Johannesburg was undertaken. Intersections between migration, maternal health and life in the city were explored through semi-structured interviews with 15 Zimbabwean women who had engaged with the public healthcare system in Johannesburg during pregnancy and childbirth. Interviews were dominated by reports of verbal abuse from healthcare providers and delays in receiving care—particularly at the time of delivery. Participants attributed these experiences to their use of English—rather than other South African languages; further work comparing this with the experiences of nationals is required. Beyond the healthcare system, the study suggests that the well-being of these migrant women is compromised by their living and working conditions in the city: maintaining access to income-generating activities is prioritised over accessing antenatal care services. Migrant Zimbabwean women make use of their religious and social networks in the city to inform help-seeking decisions during pregnancy and delivery. Improving the maternal healthcare experiences of urban migrant women should contribute to reducing maternal mortality in South Africa. Further research is required to inform interventions to improve the maternal health of migrant women in the city, including the multiple determinants of urban health that operate outside the biomedical healthcare system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

South Africa has alarming numbers of women dying due to complications during pregnancy and childbirth. Whilst South Africa lacks verifiable means of counting maternal deaths, estimates of overall maternal mortality (MMR) for 2007/2008 have ranged from 310 or more per 100,000 live births and most of these are caused by indirect causes (Burton 2013; Silal et al. 2012). Although MMR dropped significantly to 197 per 100,000 births in 2011, primarily as a result of extensive provision of antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) to pregnant women (Dorrington et al. 2014), this remains unacceptably high for a middle-income country such as South Africa.

South Africa has been a migrant-receiving country for many decades; as the economic hub of Southern Africa, the country experiences high levels of mobility into and within its urban centres—incorporating movements from both within and across its borders (Misago et al. 2010; Vearey 2012). Approximately 3.3% of the South African population is comprised of cross-border migrants (StatsSA 2012). In the Gauteng Province, where Johannesburg is located, about 7.4% of the population are non-nationals (StatsSA 2012) including some who are undocumented (Crush and Williams 2005). This lack of documentation means they encounter many obstacles when trying to access social services and resources, including public healthcare (Vearey 2011).

A significant number of those moving to cities are women—a phenomenon to which contemporary policy and scholarly attention are being drawn (Kihato 2009; Lurie and Williams 2014). At a global level, the percentage of migrant women is currently estimated at 49%; however, within the Southern African Development Community (SADC) subregion, it is estimated to be lower—at 45% and 42.7% in South Africa (The Observatory on Migration 2011). Nonetheless, in countries like Angola, Mozambique and Malawi, the percentage of women participating in migration streams is higher than that of men (53%, 52% and 51%, respectively), emphasizing the continued feminisation of migration in Southern Africa and its socio-economic significance (IOM, SAMP 2005). Despite these data—and with some notable exceptions (e.g. Palmary et al. 2010)—there is a lack of regional gendered analysis research, particularly in respect to understanding women’s experiences as migrants (Lefko-Everett 2007). Where research and literature do exist, it tends to focus on migrant mothers in terms of separation from their children (mothering from a distance) and the subsequent impact on families and especially those “left behind”. Whilst important, this literature fails to adequately capture the experiences of the women who are featured in this paper—migrant women who have and create families within the urban spaces that they work—and who have to navigate issues of childcare, accommodation and especially access to healthcare. Yet, female migrants have been recognised as an important group for targeted public health interventions as increasing evidence points out that migration can adversely affect the health of migrant women who are likely to be of reproductive age and to experience associated health concerns (Dias et al. 2010). In recognition of this, a small—but growing—body of literature explores the maternal healthcare experiences of migrant women in South African cities (e.g. Hunter-Adams 2016; Hunter-Adams et al. 2016; Hunter-Adams and Rother 2016).

Inner-city Johannesburg has been a central business node since the end of apartheid (Ahmad et al. 2010). Since then, central districts—such as the inner-city suburb of Hillbrow—have become a favoured destination for predominantly black job seekers from within and outside of South Africa; the proximity to social amenities such as hospitals, clinics, schools and social networks is an additional attribute that makes inner city Johannesburg an attractive location for both local and cross-border migrants (Ahmad et al. 2010). Migration and health are associated in multiple, complex ways, including differing experiences of (public) healthcare (Vearey 2012). The health experiences of migrants in South Africa reflect the heterogeneity of the migrant population (Vearey 2014), involving different help-seeking decisions and strategies (Vearey 2012): migrants move not only across geographical borders but also across, between and amongst varied medical systems, both biomedical and traditional (Sargent and Larchanché 2011).

In South Africa, various pieces of legislation have outlined the ways in which both citizens and non-citizens can access public healthcare. The initiative of the first democratically elected government in South Africa was to remove user fees for all pregnant and lactating women and children under 6 years of age at public healthcare facilities (Silal et al. 2012). Additionally, the South African national constitution section 27 ((2) and (3)) makes provision for universal access to healthcare regardless of nationality. Despite South Africa’s “health for all” policy, challenges still exist for non-nationals trying to access healthcare services in the country (Human Rights Watch 2011; Vearey et al. 2016) but little is known regarding migrants’ maternal healthcare experiences.

A survey of recent Zimbabwean migrants to South Africa showed that more recent migrants were staying longer, returning home less frequently and increasingly viewing South Africa as a place for long-term residence (Crush et al. 2012). This shift in immigration behaviour towards greater permanence makes the question of access to and quality of healthcare even more significant for Zimbabwean migrants working and living in South Africa—particularly those who cannot afford private sector healthcare (Crush et al. 2012).

Despite facing numerous access challenges and experiencing discrimination and abuse from healthcare providers when engaging with the public healthcare sector, existing evidence shows that non-nationals have developed ways to successfully navigate the system (Vearey et al. 2016). The experiences of migrant women in accessing maternal and antenatal care within the public healthcare system are, however, poorly understood. In this paper, we report on the findings from a study exploring the maternal healthcare experiences of migrant Zimbabwean women in Johannesburg. The study investigated interactions with public healthcare providers and other forms of help-seeking, such as private doctors, churches and social networks within the city. Our findings show how the living conditions of the city impact the experiences of migrant women by influencing health- and help-seeking decisions and emphasise the urgent need to acknowledge and better understand how the social determinants of urban health (SDUH) (Vlahov et al. 2007) mediate maternal health and the well-being of migrant women in the city.

Methodology and Analysis

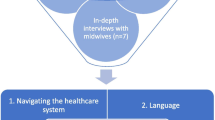

The fieldwork was undertaken by the first author between September and December 2013. Interviews were conducted with 15 Zimbabwean women (one interview session per participant, ranging between 40 min and 1 h and 10 min) aged 18 and above who were living in the inner-city Johannesburg suburbs of Hillbrow and Braamfontein. Inclusion criteria for the study required that participants had been living in South Africa for at least 2 years and had attended (or were currently attending) public sector antenatal care (ANC) services and had given (or were planning to give) birth at public healthcare facilities in inner-city Johannesburg. The inclusion of currently pregnant women was an attempt to address concerns with recall bias. Interviews were limited to experiences of ANC and delivery within the preceding five-year period. Purposive and snowball samplings were used to recruit participants; the first author made use of existing social networks with Zimbabwean families in order to identify the initial participants.

Interviews explored current and past experiences of pregnancy and childbirth in the city and focussed on four key areas: (1) background information and migrant status, (2) maternal healthcare experiences, (3) family and social support and (4) future plans in case of a further pregnancy. Three participants did not consent to their interviews being audio recorded due to their concerns that the recordings may be shared with people other than the researchers. Some participants who were currently pregnant indicated concern around the belief that the recordings may “fall into the wrong hands” and lead to them being used to harm their unborn babies. For these three interviews, detailed notes were taken during the interviews. Most (13) of the interviews were conducted in Shona, the native language of the first author and the majority of the participants. Only two interviews were conducted in English. Interviews were transcribed and, where necessary, translated into English and then cross-checked for accuracy and quality by the first author. General observations and field notes were also recorded and are drawn upon in the analysis and discussion below. All participants were given pseudonyms, and no identifying information was collected. Ethical approval was granted by the University of Witwatersrand (non-medical). Thematic content analysis (Anderson 2007) was applied to the data. This allowed grouping of collected data into major themes and sub-themes, and representative quotations were arranged in table form to allow for comparisons between participants.

Results and Discussion

Six key themes—reflecting the challenges experienced by participants when accessing public antenatal and maternal healthcare in Johannesburg and ways of compensating for this through other forms of support—were identified: language as a form of control, the othering of Zimbabwean nationals by healthcare providers, the power of healthcare providers to deny access to care, livelihoods and informal sector employment as determinants of health, religion and church as alternative help-seeking strategies and the role of social networks as mediators of access to care. These themes—which present an opportunity to explore experiences of migration, health and life in the city through a maternal healthcare lens—are presented below.

Language as a Means of Control

“I think it was the first day I went to register. We were all taken inside; we were asked questions to do with maternity and child birth, like why babies need to be immunized against diseases like Polio. We were all mixed, foreigners and locals, then a Zimbabwean woman responded in English and she was sent away. They asked another question and picked on a Zimbabwean again and she responded in English and she was sent out again. That’s when the nurse said if you know you don’t understand or speak Zulu you better go, if you are Zimbabwean why don’t you go for antenatal in Zimbabwe? I was only left alone because I can speak a little Zulu so that’s how I survived. I registered but later on I had problems with my legs. I went back to the hospital and to explain my problem in Zulu was a challenge. I had to use English to be understood; that’s when I was told they could not assist me—I had to go to Zimbabwe”.

Maria Footnote 1

Language was identified as the greatest challenge faced by participants in accessing public healthcare services. This did not relate simply to challenges that may be associated with speaking a different language—such as misunderstandings or miscommunication. Rather, language was used by healthcare providers to “screen” patients based on their identity as a non-national, resulting in the verbal abuse of patients. Healthcare providers were reported to demand that the participants speak in local South African languages—such as Zulu and Sotho—but not in English. As highlighted above by Maria—who has been residing in Hillbrow for the past 4 years and had delivered the last of her six children in South Africa, these demands made communication difficult and sometimes resulted in the denial of healthcare services.

“They don’t want to hear even the slightest English from a black person, they say we are not whites here, so do not speak to us in English. They understand English but they do not want to communicate in English, when they say that they then start to speak in Sotho or some deep Zulu where you cannot understand them. If you tell them that you can’t speak any of their language they will tell you to go back to Zimbabwe since they can’t assist you so it doesn’t help at all”.

Fatima

The resentment of English can be traced and connected to the issue of colonisation and race in South Africa: white (European, English speaking) control was (is) interrupted through forms of resistance, including that of language (Seekings 2010); Whitehead 2013). The sentiments from Maria and Fatima resonate with previous research demonstrating that the use of English by Zimbabweans attracts hostile responses (Crush and Tawodzera 2014). Field notes highlight intersections between anger and hostility by staff, with those of race and language:

“What makes those nurses to be angry and shout is the failure [of patients] to follow instructions properly, language is the main problem especially at [health centre] they mostly use their local languages, maybe because there are many black nursing staff, than at [hospital]”.

Field notes, 19 October 2013

The working environment of healthcare providers and the delivery of professional duties are used as a space in which to assert dominance and independence (Makandwa 2014). The languages spoken by healthcare providers and users mediate experiences of access to public healthcare for migrants in the city; this is further exacerbated by the unavailability of interpreters and the resentment of English displayed by some healthcare providers (Davies et al. 2010; Vearey 2011; Crush and Tawodzera 2014; IOM 2013; Moyo 2010; Tlebere et al. 2007).

Participants reported significant delays at the healthcare facilities they attended; they felt that they were ignored if they spoke in English and/or staff pretended not to understand what the migrant healthcare user was saying. The sentiments expressed above by Fatima, an undocumented mother of one, were shared by other participants. Tomara, for example, a university postgraduate student and pregnant for the first time, decided to change facility to a private hospital because she was constantly ignored at the healthcare centre she attended and was uncomfortable asking questions to the healthcare providers there.

“The language made it very difficult for me at [health centre] so that’s when I decided let me go to private since it was so uncomfortable for me. I could not ask them questions as I felt very intimidated, the ladies there have very high pitched voices and it’s the same as at [hospital]; it makes them unapproachable. So they should change tone and language”.

Tomara

This study highlights that the use of language can be used to deny or delay access to public healthcare by healthcare providers, representing an informal practice of (im)migration management. Providers devise their own strategies to identify and control how non-national migrants access healthcare in inner-city healthcare facilities—which runs counter to the provisions made in law: a clear case of street level bureaucracy (see Gilson 2015). By demonstrating their resentment of the use of English, healthcare providers are engaging in a strategy that demonstrates to other nationalities that South Africa is—according to them—a country whose public healthcare system is only for black South Africans.

Non-nationals as “the Other” and as a Burden

Some of the participants spoke about being segregated by healthcare providers during ANC visits and when they came for delivery. As outlined above, this was manifested as being shouted at and/or experiencing delays in access to care at the facilities. Public perceptions in South Africa generally position migrant populations as undesirable; hostility towards migrants and refugees makes South Africa one of the most migrant unfriendly countries in the world (Landau 2005; Crush and Tawodzera 2014). Such hostility towards non-nationals is in direct contradiction with the South African Constitution and the Bill of Rights when it comes to access to public healthcare.

Participants described how they felt that they were identified and separated from South African nationals and treated differently. This harmful practice of othering based on ethnicity and nationality has negative consequences on the delivery of healthcare services and on the practitioner’s clinical conduct (Grove and Zwi 2006; Willen 2012).

“I would just say if they stop segregating it will be good, they should just treat patients equally. They should not give service according to nationality but just serve everyone as a patient not South African, Zimbabwean or Mozambican. Segregation is the most rampant challenge in the community clinics. They should love every patient and be polite and kind. They also should not ignore patients when they call for help. They should constantly check on patients”.

Maria

The sentiments expressed by Maria highlight some of the challenges commonly reported to be experienced by non-nationals in public healthcare facilities; the positioning of migrant healthcare users as “the other” can result in poorer treatment and reflects little respect and care from providers (e.g. Crush and Tawodzera 2014; Vearey et al. 2016). South Africa’s public health history is permeated with discrimination (Coovadia et al. 2009), and healthcare providers have been found to be responsible for importing their own personal and social priorities into their working environment—negatively affecting professionalism (Andersen 2004). In inner-city Johannesburg, some patients are treated with attentive kindness and respect while others are made to wait and are treated with impatience and discourtesy. Maria recounted her experience:

“The other nurses appeared to be busy with other patients. The one who was meant to attend to me was sleeping on the passage way on the heater, it was in May and it was very cold. She was claiming that they were so tired of only attending to Zimbabweans, we have had a number of Zimbabweans today and you could be the 17th today. We need to rest; you Zimbabweans are giving us too much work whilst no South African is coming. So I went to the hospital but ended up giving birth on my own with no professional assistance”.

Maria

The most striking trend shared by all participants was that once their identity as Zimbabwean was revealed, they felt that quality of care they received was reduced and they experienced abuse from healthcare providers. Ideas of “foreignness” and perceptions by healthcare providers that non-nationals, particularly Zimbabweans, are “coming in numbers” further support the anti-foreigner sentiments of many South Africans who position foreigners as a burden to the healthcare system and that they come to (ab)use and benefit from South Africa’s public services (Landau 2005; Vearey 2014).

Who Cares?

During the interviews, participants often spoke positively about their interactions with student nurses, comparing them to their negative engagements with more senior, qualified nurses. In addition, comparisons were made between the attitudes of black nurses versus white nurses towards them as migrant patients. The experiences reported by participants suggest that a hierarchy of abuse exists within the healthcare system, with the qualified nurses having the power to delay or deny patients healthcare:

“(…..) the student nurses are the ones who were helpful and caring; the qualified ones were so terrible. They did not even care for patients, especially if they know that you are a foreign patient they will just leave you”.

Fatima

During delivery, Fatima, Maria, Kudzai and Memo reported that student nurses came to their rescue, often doing so discretely because of their own fear of the senior nurses. However, Lundi (an undocumented mother of one, who has been in South Africa for nearly 3 years) had a different experience altogether, as she was reportedly sent home whilst she was already in active labour. Whilst this is not an uncommon experience, some might experience such an event in terms of differing cultural expressions of pain (Callister 2001, Callister 2003). The key issue here is that the participant felt that her nationality and documentation status influenced her treatment and therefore her experience of public healthcare.

“It was at [hospital], I don’t know why the doctor failed to pick that I was in active labour already without sending me back home. But they were student doctors, although still I don’t know what really made him to send me home”.

Lundi

Age of the nurses reportedly influenced the experiences of participants included in this study and appeared to be associated with a preference for being assisted by younger nurses:

“If it was younger nurses I think they were going to assist patients with love and patience. For maternity care I think they should put younger women not older ladies they are so impatient and to them they have seen so many women deliver such that they think women are a nuisance”.

Maria

Maria adamantly defended her preference for younger healthcare providers but took a different tone when asked to clarify her position; it becomes clear that she actually preferred student nurses, describing older qualified nurses as being impatient with patients and having negative attitudes towards patients. Maria explained her decision to change facilities in order to be assisted by white healthcare providers:

“At [hospital] they say it’s better because there is so many white healthcare personnel, the whites are better. They are not bad to us foreigners, they sympathize with us. [Hospital] is better than [healthcare centre]. At [healthcare centre] there are too many Zulus and they hate Zimbabwean”.

Maria

From the sentiments shared by Fatima and other participants, whilst younger, student nurses are viewed as more sympathetic and more helpful, senior, qualified healthcare providers are portrayed as holding the centre of power; they have the power to shout at and/or deny healthcare to migrant patients (Moyo 2010. The reported differences in experiences with younger/older, student/qualified nurses raises further questions: is this due to age and changing perceptions amongst younger staff? Or is it to do with the demonstration of power by older nurses?

Participants also expressed different perspectives about the help from their family members—spouses, mothers, sisters and sisters in law. These ranged from feeling that they received no help at all, to enjoying family support. For example, Kudzai—who worked as a hairdresser—reported that her husband was in prison during her pregnancy, where he later died. She explained how his family refused to support her, despite his relatives living nearby.

“They did not help with anything although they knew and some of them are here in Johannesburg”.

Kudzai

Tomara—who was a student at the time of her pregnancy—highlights how negotiation of access to healthcare is mediated by several people; she was a beneficiary of her father’s medical insurance and therefore able to access both private and public healthcare:

TM: You were using student medical aid, is it the momentum for students?

Tomara: No my dad also works here so I’m a beneficiary on his plan but it just did not cover everything comprehensively. I don’t know—maybe I was not meant to fall pregnant at that time but it didn’t cover all the costs.

TM: You were using your parents’ medical aid not your husband’s?

Tomara: Yes because it’s the one I have been using since and I haven’t changed surnames so I still use it and my dad pays but my husband meet the cash component.

The two cases highlight the different ways in which maternal health can be influenced by the social and family dynamics associated with life in the city.

Beyond the Healthcare System: Livelihoods and Informal Sector Employment

Livelihood activities in the city emerged as a central theme; the maternal healthcare experiences of the participants reflected their reasons for being in Johannesburg—in search of improved livelihood opportunities. They revealed insights into the nature of their employment activities, highlighting how factors outside the healthcare system were central in determining their healthcare-seeking behaviour and health status. Participants shared how they would work until they are due for delivery; the majority were self-employed in the informal sector, occupying the lower status jobs with no support or provisions for funding to support themselves if they were not working, including for maternity leave. An emphasis on their descriptions of work as being formal or informal took centre stage and, consequently, highlighted the need to analyse the working conditions associated with (in)formality and how these relate to the maternal health experiences of migrant women in the city. The interviews show how well-being in the city is compromised by the living and working conditions that migrant Zimbabwean women find themselves in, concerns that fall beyond the healthcare system—even though they are what directly impacts health, well-being and access to care. In this study, the majority of the women were employed in the informal sector either as hairdressers or informally trading in the streets. There were four exceptions: at the time of the study, Vaida—a university graduate holding a quota work permit—was formally employed in the insurance sector and gave birth in the inner-city Tomara was a full-time university postgraduate student; Dorren held both a diploma and quota work permit and was in formal employment; and Tinto who held a permanent residence permit but was not working.

Some participants emphasised their decision to put survival in the city ahead of their immediate healthcare needs. This sacrifice of health and well-being in order to access/maintain access to a livelihood opportunity has been documented elsewhere (for example, Blaauw and Penn-kekana 2010). More fundamentally, the maternal healthcare experiences of the migrant women who participated in this study make visible the ways in which intersecting social determinants of health are at play in inner-city Johannesburg; participants work tirelessly, sometimes risking their own safety, in order to access money needed for survival in the city. Memo explained how her healthcare seeking is mediated by her experiences of working in the city:

“For me I don’t want to lie, because of the fact that I am self-employed, I sell in the streets and sometimes I go with big orders back home, sometimes I could skip or miss ANC visits, because I also wanted money, which resulted in me attending only two ANC visits, and then the delivery day”.

Memo

Some participants highlighted their reasons for not seeking ANC services, which were found to be more complex than they originally appeared. Initially, Kudzai explained how her employer did not allow her time off work to access ANC. She indicated that because she did not feel unwell, she did not feel the need to access ANC services.

“I was working every day. I was staying alone, so I was not getting time, at work my boss did not give me time. I was not really bothered to go and also because I was not sick, I was fit and I never needed medical attention. I was doing alright”.

Kudzai

However, further discussion revealed a more complicated situation; Kudzai revealed her fears of attending the clinic, which appeared to be the main reason that she did not seek ANC services. This is critical: migrant women may be presented (by others) as being irresponsible for not attending ANC services and/or as not caring about their health and that of their unborn child. The experiences of participants in this study, however, clearly emphasise how migrant women make decisions about when and how to access care; these decisions are informed and mediated by the experiences of other non-nationals.

“I also heard from others at work that at the clinic the nurses shout at you, so I just said let me avoid going there so that I just go once and get shouted at once. I was scared of them shouting at me so I withdrew from going so that I will go at delivery and they shout at me once and for all”.

Kudzai

Although those who were employed informally experienced challenges in accessing care and balancing time at work and time attending ANC appoints, Vaida—who was formally employed as an insurance consultant—had a different experience altogether:

“I had so much support from my immediate family, from the maid and even from work. From the very first time people were supporting me, they were very supportive even my boss with my first pregnancy. I started my maternity leave very early, maternity leave here is 4 months but mine was close to 5 months”.

Vaida

This shows how formal employment may support paid time off work—i.e. maternity leave. In comparison, being employed in the informal sector—like the majority of the women who participated in this study—requires a lot of investment in terms of energy and time (Makandwa 2014). These experiences emphasise the importance of social and economic factors in shaping health-seeking behaviours during pregnancy and delivery, advancing an argument that runs counter to the positioning of pregnancy as one in which women require specialised care and attention. Rather, these migrant women show how immediate their needs are prioritised over later health concerns: preventative healthcare seeking (i.e. ANC services) are secondary to immediate economic needs and associated income-generating activities in the city.

Religion and Church as Support

The role of religion and churches as spaces of support emerged as one of the central themes in this study. As found in other studies, churches played a crucial role in providing emotional, instrumental and informational support to the participants in preparation for childbirth (Harley and Eskenazi 2006). The participants—particularly Ayanda, Maria, Kudzai and Fatima—acknowledged going to church and receiving prayers, advice and exercises during pregnancy. Some of the women stated that they did not go to church specifically for divine intervention; they viewed themselves as believers for whom attending church and obtaining support from the church were seen as a normal part of their life. Fatima, however, recounted how she constantly went to church to seek divine intervention:

TM: when you were pregnant did you ever look for help elsewhere beside the hospitals?

Fatima: I was going to church because I’m a believer.

TM: What kind of help did you get from church?

Fatima: We were given holy water and oil. So I would drink that water and make porridge from the water and put the holy oil in it.

TM: Would you mind explaining in detail how things are done for pregnant women at your church?

Fatima: We are prayed for, they give us exercises to do to keep fit, together with the holy water and oil for protection.

However, a closer analysis of Fatima’s experiences during pregnancy provides a lens into the discrimination and challenges which affected her attitude towards public healthcare facilities to the extent of deciding sometimes to buy over the counter medication when not feeling well during pregnancy. Church, for Fatima, provides an alternative way of seeking help and medication, and navigating the healthcare system—highlighting the relevance of the plural healthcare system existing in the city.

Ayanda—an undocumented mother of one—provides insight into the intersections between health, spiritual guidance and their church and family “back home”:

“Here I don’t go to church but I constantly phone home to get spiritual guidance from my church. That is also the church where my parents go. My mother was so supportive during my time of pregnancy sometimes she will call if some prophecy was done at church and solutions recommended, and she will always urge me to use holy oil and Alfa and Omega holy water during bathing and preparation of food”.

Ayanda

Although Ayanda is physically far away, she remains spiritually close; distance did not interfere with her support network as communication technology allowed her to maintain these linkages. Nzayabino (2010) argues that in the process of negotiating their livelihoods in host communities—especially for those migrants staying in urban areas—religion and spirituality can become central in their lives. Prayers and prophetic guidance also give assurance and reassurance that, at the end, the period (pregnancy and delivery) will be a success and free of complications.

“……..I am a believer and I was born in a Christian family and I used to go to church for prayers and anointment for protection during my pregnancy and childbirth, nothing much”.

Kudzai

These experiences speak to the relevance and importance of religion, belief systems and churches to migrant women, both during pregnancy and after giving birth, providing insights into the multiple belief systems associated with health and well-being.

These forms of help-seeking behaviour emphasise that participants do not entirely trust the medical healthcare system for their health and well-being; this is further compounded by the negative experiences of public healthcare highlighted above.

Networks: Mediators of Access to Healthcare

Different life events demand different kinds of support (Hunter-Adams 2016). Informal, social networks were found to be central in influencing the health- and help-seeking behaviours, attitudes and perceptions of the participants towards ANC and the public healthcare system. Information shared informally appears to influence decisions about which healthcare facility to attend (or not) and some of the participants indicated their future plans for changing facilities should they find themselves pregnant again. The interviews revealed that friends and fellow Zimbabwean migrants are at the centre of the women’s social networks in the city. These informal communication channels can disseminate both helpful information about access and the experiences of other women, as well less helpful, unsubstantiated rumour in relation to specific healthcare facilities and access to public healthcare more generally; family, friend and community structures have important implications for health- and help-seeking behaviours (Hunter-Adams 2016).

Participants described their reasons for missing ANC appointments or delaying access to ANC, highlighting how these are connected to the (mis)information received through their social networks, and the role of associated rumours, confusions and misunderstandings in mediating these decisions. Fatima and Memo shared the confusions that resulted from the information they received through their informal networks. As a result, both delayed healthcare seeking. Fatima registered her pregnancy late—when she was 7 months pregnant, only then that she visited the clinic as she needed to get a referral for delivery.

“I was just discouraged, because everyone was saying you have to wake up very early in the morning. They also told me that they wanted a valid passport to register you. So I thought I was just going to go to a hospital to deliver, that’s when I heard that you will not be taken in for delivery without a referral from a clinic or another facility showing you attended antenatal care”.

Fatima

Memo—based on what she had heard through her social networks—presented late during labour.

“I decided not to go there at [healthcare centre] early because I heard that if you go to the hospital early they will operate you, if you stay longer before giving birth, that was my fear, so I delayed phoning the ambulance until I was so sure that I was about to give birth”.

Memo

These informal channels of information can influence behaviour and attitudes towards the healthcare system, consequently affecting decisions about whether—or not—to access healthcare, particularly as linked to the presumed acceptability (or not) of the services (McIntyre et al. 2009).

Informal social networks are a space where information—both factual and not—is shared amongst migrant women in the city. These networks are central in influencing decisions about accessing public healthcare: rumour and stories of the experiences of other women shape their attitudes and perceptions about healthcare providers and institutions in the city, and they act as a coordinating mechanism between participants, helping them navigate the healthcare system.

Conclusion

Our study provides insights into the maternal healthcare experiences of migrant Zimbabwean women in Johannesburg who are reliant on an over-stretched and over-burdened public healthcare system. Contributing to a small, but growing, literature exploring the maternal healthcare experiences of migrant women in the city, it is hoped that the findings presented here support improved understanding into the public healthcare challenges faced by urban migrants in south and southern Africa.

We have shown that the urban context mediates health and well-being and influences decisions relating to help-seeking strategies. The experiences shared by the women who participated in this study show that health is subjective and personal, and our findings highlight ways of navigating plural healthcare and help-seeking systems, including the role of medical aid and private healthcare, religious and spiritual interventions and social networks. Through exploring the maternal healthcare experiences of 15 Zimbabwean women in the city, we have shown that decisions relating to maternal healthcare during pregnancy and childbirth are influenced by many factors and move beyond a narrow biomedical focus to one that is influenced by a complex array of economic, social and religious factors. Decisions relating to healthcare and help-seeking are far more personal and emotional than many healthcare-focused interventions presume.

The Zimbabwean women who participated in this study experience multiple challenges and significant delays in accessing public maternal healthcare services. Key here is the use of English, as opposed to other South African languages: women are delayed or denied healthcare when they speak in English, reprimanded or shouted at. Experiences of abuse impact negatively on a willingness to continue seeking healthcare, resulting in women making decisions to skip their own ANC visits, risking their health because of fears relating to the way they are treated developing over time. These experiences are shared with other Zimbabwean women who—based on stories they hear from others—may also choose to delay seeking care.

City life negatively impacts the maternal healthcare experiences of the participant Zimbabwean women as they struggle to balance healthcare needs with the competing demands associated with surviving in the city. Establishing ways to support religious and social networks in helping migrant women navigate maternal healthcare is of central importance, as is working to address the othering of foreign migrant women in South African healthcare facilities. The issue of access to quality public healthcare for migrant Zimbabwean women raises further questions about how their experiences compare to those of South African women—specifically the urban poor, who are not on medical aid and are often mobile. In order to improve health for all, and to address MMR in South Africa, further research is urgently needed to inform improved responses to maternal healthcare in the city.

Notes

Pseudonyms are used throughout the paper

References

Ahmad, P., Chirisa, I., Magwaro-Ndiweni, L., Muchindu, M.W., Ndlela, W.N., Nkonge, M., Sachs, D., 2010. Urbanising Africa: the city centre revisited—experiences with inner-city revitalization from Johannesburg (South Africa, Mbabane (Swaziland), Lusaka (Zambia), Harare and Bulawayo (Zimbabwe), 26/2010, IHS: Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies, viewed 16 January 2013.

Andersen, H. M. (2004). “Villagers”: differential treatment in a Ghanaian hospital. Social Science & Medicine, 59, 2003–2012.

Anderson, R., 2007. Thematic content analysis (TCA). Descr. Present. Qual. Data.

Blaauw, D., & Penn-kekana, L., (2010). Maternal health. In South African health review 2010. Durban: Health Systems Trust.

Burton, R. (2013). Maternal health: there is cause for optimism. SAMJ South African Medical Journal, 103, 520–521.

Callister, L. C. (2001). Culturally competent care of women and newborns: knowledge, attitude, and skills. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 30, 209–215.

Callister, L. C. (2003). Cultural influences on pain perceptions and behaviors. Home Health Care Manag. Pract, 15, 207–211.

Coovadia, H., Jewkes, R., Barron, P., Sanders, D., & McIntyre, D. (2009). The health and health system of South Africa: historical roots of current public health challenges. The Lancet, 374, 817–834.

Crush, J., & Tawodzera, G. (2014). Medical xenophobia and Zimbabwean migrant access to public health services in South Africa. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 40, 655–670. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2013.830504.

Crush, J., Williams, V., 2005. International migration and development: dynamics and challenges in South and Southern Africa. In: United Nations Expert Group Meeting on International Migration and Development. pp. 6–8.

Crush, J., Chikanda, A., Tawodzera, G., 2012. The third wave: mixed migration from Zimbabwe to South Africa. Southern African Migration Programme, South Africa.

Davies, A., Basten, A., & Frattini, C. (2010). Migration: a social determinant of migrant’s health. Eurohealth, 16, 10–12.

Dias, S., Gama, A., & Rocha, C. (2010). Immigrant women’s perceptions and experience of healthcare service: insights from a focus group study. J. Public Health Springer Verl. Ger., 18, 489–496.

Dorrington, R., Bradshaw, D., Laubscher, R., Nannan, N., 2014. Rapid mortality surveillance report 2012. Cape Town, South Africa. South Afr. Med. Res. Counc.

Gilson, L. (2015). Lipsky’s street level bureaucracy. In E. Page, M. Lodge, & S. Balla (Eds.), Oxford handbook of the classics of public policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Grove, N. J., & Zwi, A. B. (2006). Our health and theirs: forced migration, othering, and public health. Social Science & Medicine, 62, 1931–1942. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.061.

Harley, K., & Eskenazi, B. (2006). Time in the United States, social support and health behaviors during pregnancy among women of Mexican descent. Social Science & Medicine, 62, 3048–3061.

Human Rights Watch, 2011. Stop making excuses. Accountability for maternal health care in South Africa. U. S. Am. Hum. Rights Watch.

Hunter-Adams, J. (2016). Mourning the support of women postpartum: the experiences of migrants in Cape Town, South Africa. Health Care Women Int., 0, 1–15. doi:10.1080/07399332.2016.1185106.

Hunter-Adams, J., & Rother, H.-A. (2016). Pregnant in a foreign city: a qualitative analysis of diet and nutrition for cross-border migrant women in Cape Town, South Africa. Appetite, 103, 403–410. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2016.05.004.

Hunter-Adams, J., Myer, L., & Rother, H.-A. (2016). Perceptions related to breastfeeding and the early introduction of complementary foods amongst migrants in Cape Town, South Africa. International Breastfeeding Journal, 11. doi:10.1186/s13006-016-0088-3.

IOM, 2013. International migration, health and human rights

IOM, SAMP, 2005. HIV/AIDS, population mobility and migration in Southern Africa: defining a research and policy agenda.

Kihato, C.W., 2009. Migration, gender and urbanisation in Johannesburg

Landau, L. B. (2005). Urbanisation, nativism, and the rule of law in South Africa’s “forbidden” cities. Third World Quarterly, 26, 1115–1134.

Lefko-Everett, K., 2007. Voices from the margins: migrant women’s experiences in Southern Africa. Idasa.

Lurie, M. N., & Williams, B. G. (2014). Migration and health in Southern Africa: 100 years and still circulating. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 2, 34–40. doi:10.1080/21642850.2013.866898.

Makandwa, T., 2014. Giving birth in a foreign land: maternal health-care experiences among Zimbabwean migrant women living in Johannesburg, South Africa. Witwatersrand University, Witwatersrand University, Johannesburg, South Africa.

McIntyre, D., Thiede, M., & Birch, S. (2009). Access as a policy-relevant concept in low-and middle-income countries. Health Economics, Policy, and Law, 4, 179–193.

Misago, J.P., Gindrey, V., Duponchel, M., Landau, L., Polzer, T., 2010. Vulnerability, mobility and place: Alexandra and Central Johannesburg Pilot Survey, Johannesburg.

Moyo, K., 2010. Street level interface: the interaction between health personnel and migrant patients at an inner city public health facility in Johannesburg.

Nzayabino, V. (2010). The role of refugee-established churches in integrating forced migrants: a case study of Word of Life Assembly in Yeoville, Johannesburg. HTS Theological Studies, 66, 1–9.

Palmary, I., Burman, E., Chantler, K., & Kiguwa, P. (Eds.). (2010). Gender and migration: feminist interventions. London: Zed Books.

Sargent, C., & Larchanché, S. (2011). Transnational migration and global health: the production and management of risk, illness, and access to care*. Annual Review of Anthropology, 40, 345–361.

Seekings, J. (2010). Race, class and inequality in the South African city. University of Cape Town: Centre for Social Science Research.

Silal, S. P., Penn-kekana, L., Harris, B., Birch, S., & McIntyre, D. (2012). Exploring inequalities in access to and use of maternal health services in South Africa. BMC Health Services Research. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-12-120.

StatsSA, S., 2012. Census 2011 statistical release. Pretoria Stat. South Afr. Retrieved Httpwww Statssa Gov ZaPublications P 3014.

The Observatory on Migration, 2011. Overview on south-south migration and development in Southern Africa: trends and research needs, regional overview.

Tlebere, P., Jackson, D., Loveday, M., Matizirofa, L., Mbombo, N., Doherty, T., Wigton, A., Treger, L., & Chopra, M. (2007). Community-based situation analysis of maternal and neonatal care in South Africa to explore factors that impact utilization of maternal health services. J. Midwifery Womens Health, Special Issue Global Perspectives on Women’s Health: Policy and Practice, 52, 342–350. doi:10.1016/j.jmwh.2007.03.016.

Vearey, J., 2011. Contemporary migration to South Africa, implication for development: a regional perspective.

Vearey, J. (2012). Learning from HIV: exploring migration and health in South Africa. Global Public Health, 7, 58–70.

Vearey, J. (2014). Healthy migration: a public health and development imperative for south(ern) Africa. South African Medical Journal, 104, 663–664.

Vearey, J., de Gruchy, T., Kamndaya, M., Walls, H. L., Chetty-Makkan, C. M., & Hanefeld, J. (2016). Exploring the migration profiles of primary healthcare users in South Africa. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 1–10.

Vlahov, D., Freudenberg, N., Proietti, F., Ompad, D., Quinn, A., Nandi, V., & Galea, S. (2007). Urban as a determinant of health. J Urban Health, 84, 16–26.

Whitehead, K., 2013. Race-class intersection as interactional resources in post-apartheid South Africa. In: Pascale, C.-M. Social inequality & the politics of representation: a global landscape. SAGE Publications.

Willen, S. S. (2012). Migration, “illegality,” and health: mapping embodied vulnerability and debating health-related deservingness. Social Science & Medicine, 74, 805–811. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.10.041.

Acknowledgements

We warmly thank the 15 participants who generously shared their experiences. Thank you to the City of Johannesburg Metro Health and the Gauteng Provincial Department of Health for permission to undertake the study. Our thanks go to the healthcare providers and facilities who hosted the research project. We thank two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments that assisted in strengthening the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Makandwa, T., Vearey, J. Giving Birth in a Foreign Land: Exploring the Maternal Healthcare Experiences of Zimbabwean Migrant Women Living in Johannesburg, South Africa. Urban Forum 28, 75–90 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-017-9304-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-017-9304-5