Abstract

In this paper, we evaluate the Swedish self-employment start-up program based on a matching approach using data from administrative records. In addition to information of labor market history, traditional human capital and socio-economic variables, the data at hand also include information on the self-employment history of participants and nonparticipants as well as that of their parents. Our results indicate that the start-up subsidy program for unemployed persons is a successful program regarding the integration of the unemployed into the mainstream of the labor market. We find that, relative to members of control groups, participants, on average, have an increased probability of unsubsidized employment. Our analysis of different educational backgrounds presents the strongest employment effects for the low educated unemployed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

This paper is concerned with the labor market effects of the Swedish self-employment start-up program. The main goal of self-employment schemes is to increase the rate of outflow from unemployment and to stimulate the creation of employment in small businesses. Such schemes involve either an allowance to support the self-employed person through an introductory phase or a capital subsidy to cover part of the initial investment costs. Measures that aim at stimulating unemployed job seekers to start businesses on their own may constitute essential instruments in the toolbox of a country’s labor market policy. The most common argument for subsidizing start-ups among the unemployed is the existence of barriers for some categories of unemployed persons. It may, for example, concern capital constraints, shortages of specific business human capital, or the absence of social networks (see e.g., Meager 1996; Blanchflower and Oswald 1998). There are a number of studies focusing on the effectiveness of self-employment schemes with regard to the labor market outcomes for unemployed participants (e.g., Meager 1996; Baumgartner and Caliendo 2008; Caliendo 2009; Caliendo and Künn 2011; Michaelides and Benus 2012; Caliendo and Künn 2014 and 2015; Caliendo et al. 2015; Caliendo et al. 2016).Footnote 1

The present study evaluates the Swedish self-employment program’s effect on the labor market outcomes for its participants. Our approach regarding examining the average treatment effect on the treated adds some important contributions to previous research. Firstly, very few studies exist that examine the long-term effects of starting one’s own business to exit unemployment (see e.g., Caliendo et al. 2016). Former long-term effects of start-ups are based on a maximum of a 40 month follow up period. In this paper we use a 60 month observation period after start-up. It is important to examine whether the positive effects that have been demonstrated by start-up actions in Germany, for example, also apply within a different economic context. The activities of the Nordic countries are particularly interesting; their specific institutional arrangements create a strong link between work and compensation on the basis that the first objective is getting a job and the second is receiving unemployment benefits (Kolm and Tonin 2015).

Secondly, to identify the average treatment effect on the treated it is very important that you have access to rich administrative information of labor market histories of treated and untreated, see e.g. Fredriksson and Johansson (2008) and Caliendo et al. (2016). We have detailed information on historical data regarding the employment and earnings histories prior to the program as well as unemployment histories and personal characteristics. The administrative data contains extensive information on individual employment and unemployment histories covering 10 years before and five years after treatment started. By making use of these data, we have been able to make follow-up at two and five years after participating. Nearly all other studies provide short- to medium-term evidence. The data also enable us to extend the core analysis to include impacts relating to different levels of education.

The third contribution of this study involves the possibilities of taking the past experiences of self-employment into account. As pointed out by Caliendo and Künn (2011), previous experience of self-employment might play a key role for taking up self-employment again as occupation. Other research points to the fact that the intergenerational transmission of entrepreneurial skills is highly correlated with a person’s probability of becoming self-employed, see e.g. Colombier and Masclet (2008) and Lindquist et al. (2015). We have information about experience of self-employment and, unlike all other start-up studies, information on whether either of the examined individual’s parents has any business experience.

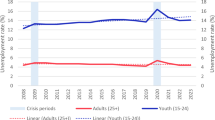

The fourth contribution to the literature is that, unlike other studies of start-ups, we study explicitly how education affects the employment effects. In OECD countries, the relative situation of low-skilled workers worsened during the last three decades (Oesch 2010). In the United States, this deterioration took the form of an increase in wage inequalities (Autor et al. 2008). In European countries, such as France, Germany, and Sweden, it led to higher unemployment rates among low-skilled workers. The activation of low-educated unemployed is an important contribution in analyzing whether active labor market policies through support to start-ups are an effective way to influence employment opportunities for different educational groups.

This paper proceeds as follows: we describe the Swedish self-employment scheme, background theories and previous studies, the strategy for estimating treatment effects, and the construction of the control groups of nonparticipants representing counterfactuals of participation in the self-employment program. We present the estimated effects of the program on such outcome variables as the transition from unemployment to unsubsidized employment. The results also include an analysis of the impact by educational background. Some discussion is presented and we conclude in Section conclusion.

The Swedish Start-up Grants Program

The Start-up Grants program, which supports starting a business, was originally introduced in Sweden on July 1, 1984. The Swedish self-employment scheme entitles its participants to six months’ income support. The compensation may be extended in some cases but only for sickness and when official authorization has been delayed. The grant is usually equivalent to unemployment compensation. The activity support is calculated, ratified, and paid out by the Swedish Social Insurance Agency. Earnings from self-employment are not deducted from the subsidy.

For eligibility, one of six different categories has to be fulfilled: 1) being at least 25 years old and registered as a job seeker at an employment service as well as being in need of enhanced support, 2) being young and having a disability that affects the ability to work, 3) being 18 years of age and far from the labor market for specific reasons, 4) meeting the conditions for participation in the Working Life Introduction Program, 5) being at least 20 years old and meeting the conditions for participating in the Youth Job Program, and 6) participating in the Job and Development Program. The job seeker makes inquiries about the possibility of being granted a start-up subsidy. In other cases, the self-employment program is brought up for discussion in dialogues between the job seeker and caseworker. If starting a business is determined to be a realistic alternative for the job seeker, she or he must present a business plan to the employment office, which in turn receives counsel from an external source regarding the commercial viability of the business venture. Participants can be offered advice and information in the initial stage of being self-employed and may, if they so desire, be given the opportunity to take part in a training course for running a business.

Theory and Previous Studies

The theoretical framework for why a person chooses to become self-employed takes as a starting point the opportunity cost of self-employment. A person is likely to become self-employed if the potential gains from becoming self-employed exceed the cost. The opportunity cost of becoming self-employed is either the wage from employment or the benefits from unemployment insurance (see e.g., Rees and Shah 1986; de Wit and Van Winden 1989; Johansson 2000; Hammarstedt 2006; Hammarstedt and Shukur 2009). Based on this framework, the literature distinguishes between a number of sources that influence the expected revenues and cost of becoming self-employed. On one hand, there are “pull” factors, where the objective for becoming self-employed is to explore business opportunities (see e.g., Dennis 1996; Blanchflower and Oswald 1998). In the literature, this type is sometimes also labeled opportunity entrepreneurs. On the other hand, and most likely the case for the unemployed, there are also “push” factors. These are factors that make self-employment the least unattractive among unattractive options (see e.g., Storey 1985; Storey and Johnson 1987; Persson 2004; Dawson and Henley 2012; Mångs 2013). These self-employed become so out of necessity, (i.e., necessity entrepreneurs). A characteristic that can be associated with both push and pull are the degree of risk aversion. According to Ekelund et al. (2005), persons that are less risk averse become self-employed to a greater extent. A factor that is likely to reduce the risk associated with becoming self-employed is if the unemployed has his or her own, or family experience, of self-employment. Dawson et al. (2009) state that, “Once a person has been pulled or pushed into self-employment they are likely to continue to choose self-employment as an occupation” (p. 6). It is, however, not only a person’s own experiences that are likely to influence preferences. Having parents that are/were self-employed increases the probability that a child becomes self-employed later in life (see, e.g., Dunn and Holtz-Eakin 2000; Shane 2003).

For our study, factors that influence the likelihood that a person will choose to become self-employed are important since these factors will introduce the possibility of self-selection into the program. Since we use a matching approach for investigating the impact of the program, we need to address both administrative- and self-selection as possible problems for identification.

Previous Studies on Start-up Grants for the Unemployed

There have been some studies in the 2000s on the impacts of programs close to or equivalent to the Swedish SEP-program. In an evaluation of business start-up support for young people in the UK, Meager et al. (2003) estimate the effect on subsequent employment status for program participants whose businesses have closed down. The analysis is based on a comparison with a group of young people whose employment status was the same as that of their counterparts on the date when the latter entered self-employment. No evidence is found that participation in the program had any impact on the participants’ subsequent employment status. Baumgartner and Caliendo (2008) compare the effectiveness of two German programs designed to stimulate unemployed persons to become entrepreneurs with other active labor market policy programs. The results of their study, focusing on West Germany, indicate that both start-up schemes are successful. At the end of the observation period, the unemployment rate was lower for participants than for nonparticipants, and both the probability of being in paid employment or self-employment and personal income were higher. In a second evaluation of the two German start-up schemes, Caliendo (2009) concentrates on East Germany and finds that both programs were successful there. The risk of returning to unemployment was lower for program participants than for nonparticipants while the probabilities of being employed/self-employed and personal income were both higher. Almeida and Galasso (2010) study the effects of a self-employment program in Argentina and find that, in the short run, the program does not produce any income gains for the average participant, even though the total number of hours worked increases. Rodriguez-Planas and Benus (2010) investigate the impacts of four labor market programs in Romania: training and retraining, employment and relocation services, small business assistance offering services to facilitate business start-ups for displaced entrepreneurs, and public employment. Their analysis reveals that the first three mentioned programs had positive effects on the labor market outcomes of the program participants. Caliendo and Künn (2011) estimate the long-term effects of the two German start-up programs against the effects of non-participation. Observing individuals for nearly five years following start-up, the researchers find that both schemes improve both employment probabilities and earnings. Michaelides and Benus (2012), who examine the efficacy of providing self-employment training in an American program, conclude that it was effective in helping unemployed persons to start a business and to transit to employment. Even five years after the program, the authors find a significant impact on avoiding unemployment. Caliendo and Künn (2014) examine the potentially heterogeneous effects of start-up programs across regional labor markets. They discover that both the development of businesses and program effectiveness are influenced by the economic conditions prevailing at start-up. Start-up programs are also interesting from a business/economic growth perspective. In a study comparing subsidized start-ups and regular business start-ups, Caliendo et al. (2015) reach the conclusion that firms that are started with a subsidy by the unemployed have, on one hand, a higher survival rate, but on the other hand, they perform worse in terms of income, business growth, and innovation. Using long-term informative data, Caliendo and Künn (2015) state that start-up programs persistently integrate formerly unemployed women into the labor market in contrast to female unemployed nonparticipants. It has been shown that personality traits affect labor market outcomes, Heckman et al. (2006). Caliendo et al. (2016) investigate the role that individuals’ personalities play for the estimation of causal programme effects under the CIA. They confirm high effectiveness of the former programmes. Their results indicates that the large set of control variables, including labor market history information, in the estimation of the propensity score, even when not directly controlling for personality, already sufficiently captures individuals´ personalities.

To sum up, the papers look at probabilities of leaving unemployment, probability of re-entering unemployment, and impacts on future income. For the cases of Germany, and the US, we find positive employment effects of start-ups, but we find no effects of supporting start-ups in Argentina and Romania. The evidence varies with respect to countries, the institutional design of the support, and entrance conditions. Most studies are either focused on parts of the labor market (e.g., young people, women, unemployed in different geographical areas of the country). Most of the studies provide evidence only for the short run. Only two studies analyses the long-run effects. To further strengthen the importance of long-term follow-up, we use a 60 months follow up period instead of 40 months. Caliendo et al. (2016) contributes to the literature with the study of personality traits and the evaluation of start-up subsidies concluding that having access to rich administrative labor history data leading to including and excluding individuals’ personalities do not significantly affect the results. To identify the effects of start-ups on employment, the identification of the selection into self-employment becomes very important. The Caliendo et al. (2016) paper shows that personality traits are correlated with labor market and human capital controls. However, according to the entrepreneurship literature the most important factor explaining why some people become entrepreneurs, but not others, is parental entrepreneurship. According to our review of the literature this is a characteristic not controlled for in previous studies.

Empirical Strategy

Estimation Strategy

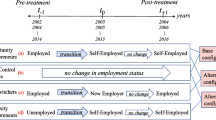

Our estimation strategy is based on the potential outcome approach, also known as the Rubin (1974) model. We denote the potential outcome of participating in the program as the potential outcome of not participating as and the actually observed outcome as Further, let signify participation and nonparticipation. We are interested in assessing the average treatment effect on the treated given by where denotes the mean in the population of program participants. The problem with the identification of is that the counterfactual outcome for participants is not observable. Assuming, however, that program participation and program outcome are independent conditional on a set of observed covariates,X, then E(Y 0|D = 1, X) = E(Y 0|D = 0, X).Footnote 2 To adjust for confounding biases when estimating impacts of having participated in the SEP, we make use of matching techniques. Our analysis compares the treated to three different categories of comparison groups i.e., multiple treatment analysis (see e.g., Imbens 2000; Lechner 2001).Footnote 3

Data

We use a data set that combines administrative data from the Swedish Public Employment Service (PES) with register data from Statistics Sweden. The major part of the data set contains information for the 2003–2007 periods; however, we also have historical information about unemployment history, employment history, and self-employment experience. Information was gathered from the PES information about jobseekers who were unemployed in 2003 and who were transferred to the self-employment program (SEP) for a six-month period starting in 2003. The number of observations in that category (the SEP category) is 15,106.

Since the purpose of the study is to evaluate the self-employment scheme as an active labor market program for unemployed job seekers, information from the PES was also collected about those that were eligible for participation in the SEP but did not join the program, see Biewen et al. (2014) for a discussion about the importance of data and methodological choices. This is a non-SEP category from which one of our control groups was selected (cf. Baumgartner and Caliendo 2008, p. 348; Caliendo 2009, p. 627). Henceforth, those in this category will be referred to as all eligible nonparticipants. The number of observations in that category is 466,691. We also decided to take into account comparisons with two less diverse control groups. In the interest of the study, the reasonable basis from which to choose such groups consists of unemployed job seekers with characteristics that match the criteria by which candidates for the self-employment program are judged. Therefore, the two other control groups used in the study were selected from subcategories taken from All eligible nonparticipants, viz.: (1) Job seekers who were registered as openly unemployed (i.e., those who were not participating in any active labor market policy program) from the category referred to in the study as Receiving only job search assistance, whose number of observations is 331,906; and (2) Job seekers who had been transferred to labor market programs other than the self-employment program, excluding programs for job seekers with occupational disabilities, form a category consisting of 127,742 persons, which in the study are referred to as Participants in other active labor market programs (ALMPs).

Identification

Our identification strategy is based on an extensive set of variables that are likely to influence program participation and labor market outcome.Footnote 4 In the matching process, the individual covariates of SEP-participants and nonparticipants are entered into a probit model to estimate their propensity score (i.e., the probability of being selected for the SEP based on observable predictors). In the following section we present and discuss the variables that entered our prediction of being selected for participating in the SEP-program in relation to theory and previous research.

To identify the effects of start-ups, controlling the selection into self-employment becomes very important. Unlike other studies of SES, we have access to the most important control explaining why some become self-employed and others not. To quote Lindquist et al. (2015, p.269-270): “Why do some people become entrepreneurs but not others? The entrepreneurship literature asserts a number of factors that influence this choice. The most prominent among these factors is parental entrepreneurship. Having an entrepreneur for a parent increases the probability that a child ends up as an entrepreneur by 30–200% (Dunn and Holtz-Eakin 2000; Arum and Mueller 2004; Sörensen 2007; Colombier and Masclet 2008; Andersson and Hammarstedt 2010, 2011).” Surprisingly, this type of information has not been used in previous evaluations of start-up grants despite its importance. As for the variables capturing parents’ self-employment experience, we have two sets of variables: mother/father self-employed 2002 and mother/father self-employed some time during 1990–2001.

In the data, we have information about a number of variables that reveal the unemployment history of SEP participants and nonparticipants which will be referred to as “pretreatment variables.” Some of these variables are related to the jobseeker’s registration period at the PES that serves as the basis of the study and some to a period of four years before that base period. Regarding the time in the base period before transition to the SEP for participants in that program or, when relevant, to another ALMP for nonparticipants, we have information about (a) number of days registered as openly unemployed obtaining baseline services from the PES and (b) total number of days registered at the PES including both open unemployment, thus obtaining baseline services and ALMP-participation. Furthermore, for a period of four years before the base period, we have information about a second set of variables: (c) Number of days registered at the PES, (d) Number of days registered at the PES as openly unemployed, (e) Number of spells of open unemployment, and (f) Number of ALMPs in which the individual has participated. With regard to the four time variables, (a)–(d), we have defined three dummy variables indicating 1–180 days, 181–365 days, and more than 365 days. The pretreatment characteristics should capture important personality traits such as individuals’ perceptions of their employment prospects, their motivation and their ability, stigma effects, and depreciation of human capital (see e.g., Fredriksson and Johansson 2008). The importance of having access to labor market history variables is also pointed out by other researchers. For example Caliendo et al. (2016) address explicitly if variables such as personality traits cause concern about the validity of the unconfoundedness assumption. Their results show no significant difference using personality traits and they conclude by these two sentences on p. 24: “One possible explanation is that personality is already implicitly reflected to a large extent by other covariates which have been affected by personality themselves. We find evidence supporting this notion, which particular emphasis on the important role of human capital attainment and labor market history.”

We also have information about such characteristics as age, gender, marital status, and ethnic origin, which together with occupation sought, have proven from previous research to be vital determinants of both labor market possibilities and the probability of becoming self-employed. Human capital information was gathered on general and occupation-specific education and on the subjective judgment of experience for the occupation sought. As noted by Sianesi (2004), the latter can be viewed as a summary statistic of the previous accumulation of on-the-job training and learning by doing. According to Ham and LaLonde (1996, p. 184), differences in this respect result from both observed and unobserved differences between the treatment group members’ and control group members’ characteristics.

Information was also obtained about indicators relevant to employment prospects such as occupational disability and whether only a full-time or only a part-time job was sought or if either of these alternatives could be accepted. We assume that persons that restrict the number of hour they are prepared to work are less likely to become self-employed.

We also have categorical information from the PES about unemployment insurance fund membership. For those with previous work experience this information will capture the sector of previous occupation. We include this information since we expect that work experience from the private sector might influence the probability of choosing to become self-employed.

As pointed out in the theoretical section, becoming self-employed is a choice made depending on the difference between opportunities and costs. This difference will be different depending on the labor market status before entering the program. We have information about the situation in 2002 regarding if the unemployed had an income from work before they entered unemployment, if a person were out of the labor force, or if the unemployed were in the labor force but getting income from social assistance. For those who were employed, we also include the income obtained in 2002 (i.e., the year prior to treatment). If a person had a job and income in close proximity before becoming unemployed, we assume that the cost associated with unemployment will be higher and therefore influence the motivation for leaving unemployment rapidly.

Another factor mentioned in the literature is access to capital to start a business (see e.g., Lindh and Ohlsson 1996). We do not have explicit information about access to capital but use income from capital in 2002 as an indicator. A negative income from capital will make it less likely that the person could obtain financing from banks, for example, while positive capital indicates that there are the individual’s own assets that can be used to finance a start-up.

As mentioned in Dawson et al. (2009), for example, an individual’s own experience is likely to reduce the expected risk associated with becoming self-employed. A contribution of this study, compared to previous research on start-up grants, is that we have information about an individual’s previous experience of self-employment. We use two variables to capture an individual’s own experience as an entrepreneur. The first variable indicates if the unemployed had been self-employed the year before treatment, and the second variable indicates if the unemployed had any self-employment experience in the 10 year period prior to becoming registered unemployed.

Finally, as pointed out in Svaleryd (2015), for example, local labor market conditions can play a role in self-employment. We include county fixed effects to control for differences in local labor market conditions.Footnote 5

Using non-experimental data could lead to selection bias. This bias is due to the fact that participants and nonparticipants are selected in groups that would have different outcomes due to observable and unobservable factors. In this study, propensity score matching is used, and thus, we rely on the conditional independence assumption (CIA). Based on this extensive set of variables presented in this section, we argue that our application make it possible to study the effects of the Swedish start-up program. However, we provide a sensitivity analysis where we assess the robustness of our results with respect to unobserved differences between participants and non-participants.

Matching Method and Estimator

We estimate the effect for each participant i by contrasting his or her outcome with the weighted average outcomes for nonparticipants j in the way given by Eq. (1), where i and j indicate each observation in the participant and nonparticipant group respectively, N 1 and N 0 are numbers of observations among participants and nonparticipants, and is the matching weights mentioned above that are placed on the jth nonparticipant (Heckman et al. 1999):

There are several estimators to choose from (see e.g., Frölich 2003; Huber et al. 2010; Huber et al. 2013). We use propensity score matching; however, as a sensitivity check, other matching estimators (propensity score as well as inverse probability) and other matching techniques (CEM-matching, see Iacus et al. 2011) have been used. The results fall within the range of +/− 2 percentage points depending on the matching estimator and method.Footnote 6

Test for Hidden Bias

As in all observational studies, the reported impact and its inference are based on the assumption that there are no unobserved cofounders and that all relevant explanatory variables have been included in the selection model. There is no obvious way to test this assumption; however, Rosenbaum (2002) provides a test to assess the robustness of the matching estimator–the Rosenbaum bounds sensitivity test.Footnote 7 The idea behind the Rosenbaum bounds test is that the probability for an individual i (π i ) to be selected is not only determined by the observed covariates (X) but also by some unobserved factor u i . Thus:

In the absence of hidden bias, the parameter γ = 0. However, if γ is significantly different from zero, hidden bias exists.

The Rosenbaum bound test is constructed so that it is targeting the opposite question, i.e. how much would an unobserved covariate have to influence the probability to be selected in order to make an significant impact estimate insignificant. The sensitivity analysis asks how much hidden bias can be present before the qualitative conclusions of the study begin to change. The test uses the sensitivity parameter Γ to indicate hidden bias. For each gamma greater than one an interval of p-values are obtained. This interval reflects the uncertainty due to hidden bias (cf. Rosenbaum 2005, p. 1810). To determine the level of uncertainty we identify the smallest gamma value for which zero is contained in the p-value interval on a chosen level of significance. For example; assume that the p-value intervals do not contain zero until Γ = 2. This result is interpreted as that the confidence interval for the treatment effect would include zero if an unobserved characteristics doubled the probability to be assigned to treatment, but also that this characteristic almost perfectly predicted the difference in outcome between treated and untreated (see e.g. DiPrete and Gangl 2004).Footnote 8

Effects of the Self-Employment Program

In this section, we present our results. The analysis is performed for the whole population as well as for various levels of educational background.

The job seekers participating in the SEP are compared with samples of job seekers taken from three other categories of job seekers registered at the PES:

-

All eligible nonparticipants. This group consist of all unemployed that are registered at the public employment office.

-

Receiving only job search assistance. This group includes those who, while being registered at the PES, remained listed as openly unemployed.

-

Participants in other ALMPs. This group includes those who were transferred to programs other than the SEP.

As outcome variables, we use the probability of leaving unemployment for paid employment, self-employment, or taking up education outside the ALMP programs.

In Table 1 we compare the matched sample of SEP participants with matched samples of the three non-SEP categories with respect to the probability of leaving unemployment for paid or self-employment. We use two points of time, December 31, 2005, and December 31, 2007, as the end dates of the follow-up periods. These dates correspond to a two-year and a five-year follow-up period. In Table 1, the different follow-up points are labeled before 2006 and before 2008.

The figures in Table 1 show that, at both follow-up points, there was a considerably higher probability for SEP participants than for non-SEP participants of having transited to unsubsidized employment. The differences are statistically significant.

Table 1 reports the results regarding the average treatment effect on the treated. There is some variation in the results depending on which control group is used and the length of the follow-up period. The largest impact reported occurs when the SEP group is compared to participants in other ALMPs. The impact estimate, as compared to those participating in other ALMPs, is that the probability of having left unemployment for employment is increased by 43.5 percent-age points. The lowest impact estimate occurs when we compare with the same group but add a five-year follow-up period. In this case, the positive impact estimate shows an increase in the probability of leaving unemployment by 34.9 percentage points. Overall, the results point to the fact that the SEP is a successful program regarding the possibilities of getting a job or entering regular education after participating in the SEP program.

In the last column, the gamma value for the Rosenbaum bounds test for the binary outcomes is reported.Footnote 9 The value ranges from 5.4 to 7.4 indicating that if there were hidden bias the odds of treatment has to change between 5.4 to 7.4 times due to unobserved covariates in order to make the observed impact estimates insignificant. That is, the Rosenbaum bounds test suggests that hidden bias has to be very large to cause the true effect to be close to zero.

In summary, we find positive effects of the Swedish self-employment scheme regarding the probability of having transited to unsubsidized employment at follow-up. The results indicate that the self-employment scheme is effective in helping participants leave unemployment and receive an unsubsidized employment position. Qualitatively as well as quantitatively, our results are in line with what is reported in the literature. For example, former studies demonstrate the strong effects of such programs in Germany on the probability of not being registered at an employment office at a selected post-treatment point in time. For Germany, depending on the gender of participants and the different subprograms, for example, Baumgartner and Caliendo (2008) present a 17–28% lower probability of being unemployed for the treated, Caliendo (2009) predicts 25–40% lower probability to be unemployed for the treated 28 months after the program, and Caliendo and Künn (2011) indicate 15–20% higher employment probability for those getting a start-up subsidy compared to other unemployed.

Impact by Educational Background

In the following section, we investigate the effect of variation in the highest education obtained by participants. We have classified education level into three groups: compulsory school, upper secondary school, and further education. All groups indicate the highest educational status. In Table 2, we compare the matched sample of SEP participants with matched samples of the three non-SEP categories for different educational levels with respect to the probability of leaving unemployment for paid self-employment or taking up education outside of ALMP measures for the two- and five-year follow-up points.

The figures in the table show that, at both follow-up points, there was a considerably higher probability for SEP participants than for non-SEP participants, regardless of educational attainment, of having transited to the outcomes used. The differences are statistically significant. Depending on the year and control group we analyze, the results indicate a probability of between 29 and 51 percentage points higher for the SEP participants to be in regular employment or education. The greatest effect we can observe is among the unemployed with compulsory schooling as the highest level of education. This indicates that the SEP also presents results that go in the direction of helping mostly the low skilled. The Rosenbaum bond test points to the low probability of the existence of hidden bias due to unobserved characteristics in the data. The lowest gamma value 5.2 (further education and follow-up in 2008) indicates that the odds of treatment due to unobserved variables have to change with 5.2 in order to make the significant treatment effect insignificant.

Discussion

To find evidence on the effectiveness of policies targeted at start-ups, evaluators in practice must rely on observational studies and make use of non-experimental methods. This study essentially performs a multiple treatment analysis, as it compares the treated to three different comparison groups. Our study shows that, relative to job seekers in each of the three controls, participants in the SEP have a higher probability of transiting to unsubsidized employment.

Our empirical strategy in this study is to use propensity score matching to identify the impact of the SEP on employment. Although our empirical strategy does not rely on a pure experiment with randomization, combining information from previous research and a rich dataset containing information about the factors that might be of importance for both self- selection and administrative selection into the program, we would claim that our impact estimates are as close as one can get using non-experimental methods. Personality traits probably play a decisive role in business start-up programs. According to studies such as Sianesi (2004) and Fredriksson and Johansson (2008), the information we use is highly correlated with important unobserved personality traits and their effects (e.g., the selection into self-employment). A study by Caliendo et al. (2016) present results of the importance of personality traits on the outcome of evaluation of start-up subsidies, p.3: “We further find that the inclusion of personality variables in addition to the standard set of control variables leads to only small and mostly insignificant changes in the treatment effects.” In the sensitivity tests performed using the equivalent to the Rosenbaum bounds for dichotomous outcomes; we could see that unobserved cofounders had to influence the selection into the program quite a bit in order to make our results less creditable. A reason for this result might be that we included almost all dimensions pointed out in previous research as factors that influence preferences and motivation to become self-employed. We would especially point to the fact that we included information about the persons own, as well as the mothers’ and fathers’, experience of self-employment prior to treatment. This information has not been included in previous observational studies of self-employment programs and is, according to the entrepreneurship literature, the single strongest explanation for choosing to become self-employed, not only in the situation of unemployment but also for opportunity entrepreneurs. In Sweden, parental entrepreneurship increases the probability of children´s entrepreneurship by about 60% (Lindquist et al. 2015).

We have, however, no information about the survival of firms that were started by the unemployed who entered the self-employment program. Knowledge in that respect would make it possible to also assess the program from the point of view of its capability of stimulating the establishment of sustainable businesses.

Conclusion

This paper evaluates a self-employment start-up program based on matching and a selection of observables assumption using data from administrative records in Sweden. The main contribution of the paper is that it consider a longer follow-up window than almost all others literature on start-up subsidies and that it is based on a rich data set including, unlike other studies, information of the most important factor explaining choosing to become self-employed–namely, parental self-employment history.

Our results for the observation period show that the Swedish self-employment scheme is effective from the perspective of employment. The probability of transiting to unsubsidized employment or education is significantly higher for SEP participants than for job seekers in the matched samples of non-SEP participants. When we study different educational backgrounds, we find the strongest effects for the unemployed with only compulsory school as the highest education level, suggesting that the program also has good effects for the unemployed with difficulties in the labor market.

The research evidence on the effectiveness of self-employment assistance programs for the unemployed conducted in the late 1980s and early 1990s in Denmark, France, Hungary, Poland, the UK, the US, and West Germany do not allow for authoritative judgment of the overall effectiveness of the schemes studied. However, there is a clear picture from the 2000s. Research during this time period reveals the positive effects of start-up programs in, for example, Germany, New Zealand, and the United States, and now Sweden can be added to that list. Whether this apparent change is due to the fact that the programs become better or to changes in the labor market is difficult to determine and is a matter for future research. It may also be that the developed scientific methods are better able to capture the program impact. Our findings conform qualitatively with evidence from other studies. The studies on the German start-up programs are most similar to ours (e.g., Baumgartner and Caliendo 2008; Caliendo 2009; Caliendo and Künn 2011), and a quantitative comparison with those studies results in relatively good agreement between our results and these studies, but we present even stronger effects. This could well be a factor that relates to institutional differences between countries, but it could also be due to the fact that we in the matching stage have a rich set of variables, including parents’ experience of being self-employed, which has a very high predictive power.

Notes

One strand of evaluations of programs supporting business start-ups among the unemployed focuses on the number of jobs created by newly developed businesses and/or on their survival rates (e.g., Pfeiffer and Reize 2000; Cueto and Mato 2006; Caliendo and Kritikos 2010). However, assessment of the program as an instrument for enterprise promotion as a development strategy lies beyond our scope. For discussions of the economic case for public policy in this area, see for example Storey (1994), Cressy (2002), and OECD (2003).

Descriptive statistics of the data are presented in Appendix A.

County fixed effects are included in the regression but are omitted from the presentation.

After matching, a balancing test is performed to see whether propensity score matching successfully balanced the covariates. The results of the balancing tests are shown in Tables 4, 5 and 6 in Appendix B. The results indicate that the matched samples of SEP-participants and members of comparison groups resemble each other in most respects.

For a detailed discussion on the Rosenbaum Bounds test, see Rosenbaum (2005).

We use the user written command provided by and presented in Becker and Caliendo (2007).

References

Aakvik A (2001) Bounding a matching estimator: the case of a Norwegian training program. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 63(1):115–143

Abadie A, Imbens GW (2009) Matching on the estimated propensity score, NBER working paper 15301. NBER, Cambridge

Almeida RK, Galasso E (2010) Jump-starting self-employment? evidence for welfare participants in Argentina. World Dev 38(5):742–755

Andersson L, Hammarstedt M (2010) Intergenerational transmission in immigrant self-employment: evidence from three generations. Small Bus Econ 34(3):261–276

Andersson L, Hammarstedt M (2011) Transmission of self-employment across immigrant generations: the importance of ethnic background and gender. Rev Econ Househ 9(4):555–577

Arum R, Mueller W (eds) (2004) The reemergence of self-employment: a comparative study of self-employment dynamics and social inequality. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Autor DH, Katz LF, Kearney DH (2008) Trends in US wage inequality. Rev Econ Stat 90(2):300–323

Barnow BS, Cain GG, Goldberger AS (1980) Selection on observables. In: Stromsdorfer EW, Farkas G (eds) Evaluation studies review annual, vol 5. Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, pp 43–59

Baser O (2006) Too much ado about propensity score models? comparing methods of propensity score matching. Value Health 9(6):377–385

Baumgartner HJ, Caliendo M (2008) Turning unemployment into self-employment: effectiveness of two start-up programs. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 70(3):347–373

Becker SO, Caliendo M (2007) Sensitivity analysis for average treatments effects. Stata J 7(1):71–83

Biewen M, Fitzenberger B, Osikominu A (2014) The effectiveness of public sponsored training revisited: the importance of data and methodological choices. J Labor Econ 32(4):837–897

Blanchflower D, Oswald A (1998) What makes an entrepreneur? J Labor Econ 16(1):26–60

Caliendo M (2009) Start-up subsidies in East Germany: finally, a policy that works? Int J Manpow 30(7):625–647

Caliendo M, Kopeinig S (2008) Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching. J Econ Surv 22(1):31–72

Caliendo M, Kritikos AS (2010) Start-ups by the unemployed: characteristics, survival and direct employment effects. Small Bus Econ 35(1):71–92

Caliendo M, Künn S (2011) Start-up subsidies for the unemployed: long-term evidence and effect heterogeneity. J Public Econ 95(3–4):311–331

Caliendo M, Künn S (2014) Regional effect heterogeneity of start-up subsidies for the unemployed. Reg Stud 48(6):1108–1134

Caliendo M, Künn S (2015) Getting back into the labor market: the effects of start-up subsidies for unemployed females. J Popul Econ 28(4):1005–1043

Caliendo M, Hogenacker J, Künn S, WieBner F (2015) Subsidized start-ups out of unemployment: a comparison to regular business start-ups. Small Bus Econ 45(1):165–190

Caliendo, M., Künn, S. & Weißenberger, M. (2016). Personality Traits and the Evaluation of Start-Up Subsidies. IZA DP No. 9628, forthcoming in the European Economic Review.

Colombier N, Masclet D (2008) Intergenerational correlation in self–employment: some further evidence from French ECHP data. Small Bus Econ 30(4):423–437

Cressy R (2002) Funding gaps: a symposium. Econ J 112(477):F1–F16

Cueto B, Mato J (2006) An analysis of self-employment subsidies with duration models. Appl Econ 38(1):23–32

Dawson C, Henley A (2012) Something will turn up? financial over-optimism and mortgage arrears. Econ Lett 117(1):49–52

Dawson, C., Henley, A. & Latreille, P. (2009). Why do individuals choose self-employment? IZA Discussion Paper No. 3974. Bonn: Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit

de Wit G, van Winden FA (1989) An empirical analysis of self-employment in the Netherlands. Small Bus Econ 1:263–272

Dennis J (1996) Self-employment: when nothing else is available? J Lab Res 17(4):645–661

DiPrete TA, Gangl M (2004) Assessing bias in the estimation of causal effects: Rosenbaum bounds on matching estimators and instrumental variables estimation with imperfect instruments. Sociol Methodol 34(1):271–310

Drichoutis AC, Nayga RM, Lazaridis P (2009) Can nutritional label use influence body weight outcomes? Kyklos 62(4):500–525

Dunn T, Holtz-Eakin D (2000) Financial capital, human capital, and the transition to self-employment: evidence from intergenerational links. J Labor Econ 18(2):282–305

Ekelund J, Johansson E, Jarvelin D, Lichtermann D (2005) Self-employment and risk aversion – evidence from psychological test data. Labour Econ 12(5):649–659

Fredriksson P, Johansson P (2008) Dynamic treatment assignment. J Bus Econ Stat 26(4):435–445

Frölich M (2003) Program evaluation and treatment choice. Lecture notes in economics and mathematical systems, vol 254. Springer, Heidelberg

Ham JC, LaLonde RJ (1996) The effect of sample selection and initial conditions in duration models: evidence from experimental data on training. Econometrica 64(1):175–205

Hammarstedt M (2006) The predicted earnings differential and immigrant self-employment in Sweden. Appl Econ 38(6):619–630

Hammarstedt M, Shukur G (2009) Testing the home-country self-employment hypothesis on immigrants in Sweden. Appl Econ Lett 16(7):745–748

Heckman JJ, LaLonde RJ, Smith J (1999) The economics and econometrics of active labor market programs. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D (eds) Handbook of labor economics, vol 3. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 1865–2097

Heckman JJ, Stixrud J, Urzua S (2006) The effects of cognitive and noncognitive abilities on labor market outcomes and social behavior. J Labor Econ 24(3):411–482

Huber, M, Lechner, M. & Wunsch. C. (2010). How to control for many covariates? Reliable estimators based on the propensity score. IZA Discussion Paper No. 5268, Institute for the Study of Labor, Bonn.

Huber L, Lechner M, Wunsch C (2013) The performance of estimators based on the propensity score. J Econ 175(1):1–21

Iacus ST, King G, Porro G (2011) Causal inference without balance checking: coarsened exact matching. Polit Anal 20(1):1–24

Ichino A, Mealli F, Nannicini T (2008) From temporary help jobs to permanent employment: what can we learn from matching estimators and their sensitivity? J Appl Econ 23(3):305–327

Imbens GW (2000) The role of the propensity score in estimating dose–response functions. Biometrika 87(3):706–710

Joffe MM, Rosenbaum PR (1999) Propensity scores. Am J Epidemiol 150(4):327–333

Johansson E (2000) Self-employment and liquidity constraints. Scand J Econ 102(1):123–134

Kolm AS, Tonin M (2015) Benefits conditional on work and the Nordic model. J Public Econ 127(SI):115–126

Lechner, M. (2001). Identification and estimation of causal effects of multiple treatments under the conditional independence assumption. In: Lechner, M and Pfeiffer, F (eds.) Econometric Evaluation of Labour Market Policies, page 43–58. Heidelberg:Physica-Verlag.

Lindh T, Ohlsson H (1996) Self-employment and windfall gains: evidence from a Swedish lottery. Econ J 106(439):1515–1526

Lindquist ML, Sol J, Praag MV (2015) Why do entrepreneurial parents have entrepreneurial children? J Labor Econ 33(2):269–296

Mångs, A. (2013). Self-employment in Sweden: A gender perspective. Linnaeus University Dissertations No 146/2013.

Meager N (1996) From unemployment to self-employment: labor market policies for business start-up. In: Schmid G, O’Reilly J, Schömann K (eds) International handbook of labor market policy and evaluation. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK, pp 489–519

Meager N, Bates P, Cowling M (2003) An evaluation of business start-up support for young people. Natl Inst Econ Rev 186(1):59–72

Michaelides M, Benus J (2012) Are self-employment training programs effective? evidence from project GATE. Labour Econ 19(5):695–705

OECD (2003) Entrepreneurship and local economic development program and policy recommendations. OECD Publications, Paris

Oesch D (2010) What explains high unemployment among low-skilled workers? evidence from 21 OECD countries. Eur J Ind Relat 16(1):39–55

Persson H (2004) The survival and growth of new establishments in Sweden, 1987–1995. Small Bus Econ 23(5):423–440

Pfeiffer F, Reize F (2000) Business start-ups by the unemployed – an econometric analysis based on firm data. J Labor Econ 7(5):629–663

Rees H, Shah A (1986) An empirical analysis of self-employment in the UK. J Appl Econ 1(1):95–108

Rodriguez-Planas N, Benus J (2010) Evaluating active labor market programs in Romania. Empir Econ 38(1):65–84

Rosenbaum PR (2002) Observational studies, 2nd edn. Springer, New York

Rosenbaum, P.R. (2005) Sensitivity analysis in observational studies, in (Eds) Everitt, B.S. & Howell, D.C. Encyclopedia of Statistics in Behavioral Science, Vol. 4, p. 1809–1814,Chicester: John Wiley and Son Ltd:

Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB (1983) The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 70(1):41–55

Rubin DB (1974) Estimating causal effects to treatments in randomized and nonrandomized studies. J Educ Psychol 66(5):688–701

Shane, S. (2003). A general theory of entrepreneurship: the individual-opportunity nexus. Cheltenham (UK), Northampton (MA, US): Edward Elgar.

Sianesi B (2004) An evaluation of the Swedish system of active labor market programs in the 1990s. Rev Econ Stat 86(1):133–155

Sörensen JB (2007) Closure and exposure: mechanisms in the intergenerational transmission of self-employment. Res Sociol Organ 25:83–124

Storey DJ (1985) The problems facing new firms. J Manag Stud 22(3):327–345

Storey DJ (1994) Understanding the small business sector. Thomson Learning, London

Storey DJ, Johnson S (1987) Regional variations in entrepreneurship in the UK. Scott J Pol Econ 34(2):161–173

Svaleryd H (2015) Self-employment and the local business cycle. Small Bus Econ 44(1):55–70

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

None

Appendices

Appendix A. Descriptive Statistics

Appendix B. Balancing Tests

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Behrenz, L., Delander, L. & Månsson, J. Is Starting a Business a Sustainable way out of Unemployment? Treatment Effects of the Swedish Start-up Subsidy. J Labor Res 37, 389–411 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-016-9233-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-016-9233-4