Abstract

Academic publishing discussed in scholarships from the industry perspectives is reimagined to explore the academic publishing field from the perspectives of academics. Academic publishing is a ‘communication circuit’ in which the roles of varied the stakeholders, government, universities, publishers and libraries, are not only significant but also need to be adhered to by the academics. The significance of research publications due to the various factors, such as performance-based approach in allocation of research grants, university publishing policies contributing towards the tenure of academics require diligent analysis for understanding of the academic publishing field. A holistic approach from using the social theories is quintessential for examining the academic publishing environment inculcating the role of higher education institutes and its governing policies. This article through reimaging the academic publishing field establishes that though academic publishers are global, the publishing practices of academics are distinct to each country because academics are interdependent on the stakeholders, namely universities and government.

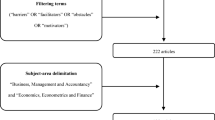

Adapted from ERA 2015 Evaluation Handbook, p. 24 [47]

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Research output is linked to funding not only in Australia but also in the UK and many European Union countries. However, the method followed in evaluating the funding applications and factors that contribute toward evaluation are different for each country.

Australia is considered as a research-focused nation when compared other nations such as India, China, South Africa or Brazil.

The journal-based publication metrics in evaluation have increased journal publications. Therefore, the discussions in the present study are predominantly based on journal publications.

Although the ERA guidelines are revised in 2018 and include assessment of ‘engagement and impact’, the previous ERA guideline published in 2016 is analysed and discussed in the present study as the publishing habits gathered from the collected data are for the period 2014–2016.

A two-digit code is used for identifying or categorising the broader area of research, while four-digit codes are used for classifying the research into specific sub-disciplines. The FoR list is available in ERA Handbook.

References

Kronman U. Managing your assets in the publication economy. Confero Essays Educ Philos Polit. 2013;1(1):91–128.

Jubb M. Introduction: scholalry communications—disruptions in a complex ecology. In: Shorley D, Jubb M, editors. Future of scholarly communication. London: Facet Publishing; 2013. p. 8–13.

Joseph RP. Higher education book publishing—from print to digital: a review of the literature. Publ Res Q. 2015;31(4):264–74.

Padmalochanan P. Academics and the field of academic publishing: challenges and approaches. Publ Res Q. 2019;35:87–107.

Fligstein N, McAdam D. A theory of fields. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012.

Jubb M. The scholarly ecosystem. In: Campbell R, Pentz E, Borthwick I, editors. Academic and professional publishing. Sawston: Chandos Publishing; 2012. p. 53–77.

Jubb M, Shorley D. The future of scholarly communication. London: Facet Publishing; 2013.

Emirbayer M, Johnson V. Bourdieu and organizational analysis. Theory Soc. 2008;37(1):1–44.

Giddens A. New rules of sociological method: a positive critique of interpretative sociologies. New York: Wiley; 2013.

Martin-Sardesai A, Guthrie J. Human capital loss in an academic performance measurement system. J Intellect Cap. 2018;19(1):53–70.

Bourdieu P. Some properties of fields. Sociol. Quest. 1993;1993:72–7.

Fischer J, Ritchie EG, Hanspach J. Academia’s obsession with quantity. Trends Ecol Evolut. 2012;27(9):473–4.

Pop-Vasileva A, Baird K, Blair B. The work-related attitudes of Australian accounting academics. Acc Educ. 2014;23(1):1–21.

Godin B. The knowledge-based economy: conceptual framework or buzzword? J Technol Transf. 2006;31(1):17–30.

Miller K, McAdam R, McAdam M. A systematic literature review of university technology transfer from a quadruple helix perspective: toward a research agenda. R&D Manag. 2018;48(1):7–24.

Hemmings BC, Rushbrook P, Smith E. Academics’ views on publishing refereed works: a content analysis. High Educ. 2007;54(2):307–32.

Auranen O, Nieminen M. University research funding and publication performance—an international comparison. Res Policy. 2010;39(6):822–34.

Liedman SE. Pseudo-quantities, new public management and human judgement. Confero Essays Educ Philos Polit. 2013;1(1):45–67.

Geuna A, Martin BR. University research evaluation and funding: an international comparison. Minerva. 2003;41(4):277–304.

Carter IM. Changing institutional research strategies. In: Shorley D, Jubb M, editors. The future of scholarly communications. London: Facet Publishing; 2013. p. 145–55.

Naidoo R. Fields and institutional strategy: Bourdieu on the relationship between higher education, inequality and society. Br J Sociol Educ. 2004;25(4):457–71.

Bourdieu P. The logic of practice. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press; 1990.

Crespo RF. Aristotle on agency, habits and institutions. J Inst Econ. 2016;12(4):867–84.

Bögenhold D, Michaelides PG, Papageorgiou T. Schumpeter, Veblen and Bourdieu on institutions and the formation of habits. Munich Personal RePEc Archive; 2016.

DiMaggio PJ, Powell WW, editors. The new institutionalism in organizational analysis, vol. 17. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2012.

Hicks D. Performance-based university research funding systems. Res Policy. 2012;41(2):251–61.

Nylander E, et al. Managing by measuring: academic knowledge production under the ranks. Confero Essays Educ Philos Polit. 2013;1(1):5–18.

Hewitt-Dundas N. Research intensity and knowledge transfer activity in UK universities. Res Policy. 2012;41(2):262–75.

Al-Khatib A, da Silva JAT. Threats to the survival of the author-pays-journal to publish model. Publ Res Q. 2017;33(1):64–70.

Marinova D, Newman P. The changing research funding regime in Australia and academic productivity. Math Comput Simul. 2008;78(2):283–91.

Nicholls MG, Cargill BJ. Establishing best practice university research funding strategies using mixed-mode modelling. Omega. 2011;39(2):214–25.

Herbert DL, et al. Using simplified peer review processes to fund research: a prospective study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(7):e008380.

Ware M, Mabe M, Report TS. International association of scientific. Amsterdam: Technical and Medical Publishers; 2015.

Das DN, Chattopadhyay S. Academic performance indicators: straitjacketing higher education. Econ Pol Wkly. 2014;49:68–71.

Sørensen MP, Bloch C, Young M. Excellence in the knowledge-based economy: from scientific to research excellence. Eur J Higher Educ. 2016;6(3):217–36.

Söderlind J, et al. National performance-based research funding systems: constructing local perceptions of research? In: Pinheiro R, et al., editors. Reforms, organizational change and performance in higher education. Berlin: Springer; 2019. p. 111–44.

Hasselberg Y. Drowning by numbers: on reading writing and bibliometrics. Confero Essays Educ Philos Polit. 2013;1(1):19–44.

Butler L. Explaining Australia’s increased share of ISI publications—the effects of a funding formula based on publication counts. Res Policy. 2003;32(1):143–55.

Butler L. Impacts of performance-based research funding systems: a review of the concerns and the evidence. In: Performance-based funding for public research in Tertiary Education Institutions: workshop proceedings; 2010. OECD Publishing: Paris.

Martin-Sardesai A, et al. Accounting for research: academic responses to research performance demands in an Australian University. Aust Account Rev. 2016;27:329–43.

Martin-Sardesai A, et al. Organizational change in an Australian university: responses to a research assessment exercise. Br Account Rev. 2017;49(4):399–412.

Cooper C, Coulson AB. Accounting activism and Bourdieu’s ‘collective intellectual’—reflections on the ICL case. Crit Perspect Account. 2014;25(3):237–54.

Sheil M. Perspective: on the verge of a new ERA. Nature. 2014;511(7510):S67.

Martin-Sardesai A, et al. Government research evaluations and academic freedom: a UK and Australian comparison. Higher Educ Res Dev. 2017;36(2):372–85.

Neave L. A recent history of Australian scholarly publishing. In: Neave L, Connor J, Crawford A, editors. Arts of publication: scholarly publishing in Australia and beyond. Melbourne: Australain Scholarly Publishing; 2007. p. 191.

Australian Research Council. State of Australian University Research 2015–16. Australian Research Council: Australia; 2015.

Australian Research Council. ERA 2015 evaluation handbook. Australian Government: Australia; 2016. p. 135.

Crowe SF, Watt S. Excellence in research in Australia 2010, 2012, and 2015: the rising of the Curate’s Soufflé? Aust Psychol. 2016;51:380–8.

Bonnell AG. Tide or tsunami? The impact of metrics on scholarly research. Aust Univ Rev. 2016;58(1):54.

Trounson A. Swinburne accused of research ratings ploy. In: The Australian; 2015.

Wilsdon J, et al. The metric tide: report of the independent review of the role of metrics in research assessment and management. London: Sage Publications; 2015.

Australian Research Council. Open access policy. Australian Research Council: Australia; 2015. p. 5.

Harley D. Scholarly communication: cultural contexts, evolving models. Science. 2013;342:80.

Petit-dit-Dariel O, Wharrad H, Windle R. Using Bourdieu’s theory of practice to understand ICT use amongst nurse educators. Nurse Educ Today. 2014;34(11):1368–74.

Vaughan D. Bourdieu and organizations: the empirical challenge. Theory Soc. 2008;37(1):65–81.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Padmalochanan, P. Reimaging Academic Publishing from Perspectives of Academia in Australia. Pub Res Q 35, 710–725 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-019-09690-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-019-09690-4