Abstract

Objective

To assess the safety and effectiveness of lumbar drains as adjuvant therapy in severe bacterial meningitis, and compare it to standard treatment.

Design

A retrospective cohort study of all patients above the age of 18 years with bacterial meningitis and altered mental status admitted to the Montreal Neurological Hospital Intensive Care Unit from January 2000 to December 2010.

Patients

Thirty-seven patients were identified using clinical and cerebrospinal fluid criteria. Patients were divided into lumbar drain (LD) (n = 11) and conventional therapy (no LD) (n = 26) groups.

Measurements

Outcomes were assessed using meningitis-related mortality and the Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) at 1 and 3 months.

Outcomes

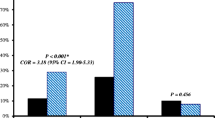

All patients received broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, 84 % received steroids. There was no significant difference in mean age, type of bacteria, or time from arrival in ER to initiation of therapy. There was significantly less co-morbidity (24 % healthy vs. 18.1 %) and coma (GCS < 8 34.6 vs. 54.5 %) in the conventional therapy group, as well as a longer duration of symptoms prior to admission (mean 1.34 ± 1.24 vs. 2.19 ± 2.34 days). The mean opening pressure was high in all patients (20–55 cm H2O in the LD and 12–60 cm H2O in the no LD). Mean time from arrival in ER to insertion of the lumbar drain was 37 h. Lumbar drains were set for a maximum drainage of 10 cc/h and an ICP below 10 mmHg. Despite greater clinical severity, the LD group had 0 % mortality and 91 % of the patients achieved a GOS of 4–5. The non-LD group had 15.4 % mortality and only 60 % achieved a GOS of 4–5. No adverse events were associated with LD therapy.

Conclusions

In this study, the use of lumbar drainage in adult patients with severe bacterial meningitis was safe, and likely contributed to the low mortality and morbidity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- Neuro-ICU:

-

Neurological intensive care unit

- LD:

-

Lumbar drain group

- no LD:

-

Conventional therapy group

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- GOS:

-

Glasgow outcome scale

- LP:

-

Lumbar puncture

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- ER:

-

Emergency room

- GCS:

-

Glasgow coma scale

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- ICP:

-

Intracranial pressure

References

Flores-Cordero JM, et al. Acute community-acquired bacterial meningitis in adults admitted to the intensive care unit: clinical manifestations, management and prognostic factors. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(11):1967–73.

Auburtin M, et al. Pneumococcal meningitis in the intensive care unit: prognostic factors of clinical outcome in a series of 80 cases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(5):713–7.

Hsu CL, et al. Management of severe community-acquired septic meningitis in adults: from emergency department to intensive care unit. J Formos Med Assoc. 2009;108(2):112–8.

Rennick G, Shann F, de Campo J. Cerebral herniation during bacterial meningitis in children. BMJ. 1993;306(6883):953–5.

Baussart B, et al. Multimodal cerebral monitoring and decompressive surgery for the treatment of severe bacterial meningitis with increased intracranial pressure. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006;50(6):762–5.

Quagliarello V, Scheld WM. Bacterial meningitis: pathogenesis, pathophysiology, and progress. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(12):864–72.

Mactier H, Galea P, McWilliam R. Acute obstructive hydrocephalus complicating bacterial meningitis in childhood. BMJ. 1998;316(7148):1887–9.

Rebaud P, et al. Intracranial pressure in childhood central nervous system infections. Intensive Care Med. 1988;14(5):522–5.

Lindvall P, et al. Reducing intracranial pressure may increase survival among patients with bacterial meningitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(3):384–90.

Bordes J, et al. Decompressive craniectomy guided by cerebral microdialysis and brain tissue oxygenation in a patient with meningitis. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2011;55(1):130–3.

Irazuzta JE, et al. Hypothermia as an adjunctive treatment for severe bacterial meningitis. Brain Res. 2000;881(1):88–97.

Macsween KF, et al. Lumbar drainage for control of raised cerebrospinal fluid pressure in cryptococcal meningitis: case report and review. J Infect. 2005;51(4):e221–4.

Archer BD. Computed tomography before lumbar puncture in acute meningitis: a review of the risks and benefits. CMAJ. 1993;148(6):961–5.

Joffe AR. Lumbar puncture and brain herniation in acute bacterial meningitis: a review. J Intensive Care Med. 2007;22(4):194–207.

Koedel U, Scheld WM, Pfister HW. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of pneumococcal meningitis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2(12):721–36.

Durand ML, et al. Acute bacterial meningitis in adults. A review of 493 episodes. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(1):21–8.

Jennett B, Bond M. Assessment of outcome after severe brain damage. Lancet. 1975;1(7905):480–4.

Teasdale GM, et al. Analyzing outcome of treatment of severe head injury: a review and update on advancing the use of the Glasgow Outcome Scale. J Neurotrauma. 1998;15(8):587–97.

Kim YS, et al. Brain injury in experimental neonatal meningitis due to group B streptococci. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1995;54(4):531–9.

Breeze RE, et al. CSF production in acute ventriculitis. J Neurosurg. 1989;70(4):619–22.

Schmidt H, et al. Streptococcal meningitis: effect of CSF filtration on inflammation and neuronal damage. J Neurol. 1999;246(11):1063–8.

Brizzi M, Thoren A, Hindfelt B. Cerebrospinal fluid filtration in a case of severe pneumococcal meningitis. Scand J Infect Dis. 1996;28(5):455–8.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the staff at the Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital, Neurological Intensive Care Unit and Medical Records who made this study possible.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Yasser Abulhasan and Hosam Al-Jehani contributed equally to this study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abulhasan, Y.B., Al-Jehani, H., Valiquette, MA. et al. Lumbar Drainage for the Treatment of Severe Bacterial Meningitis. Neurocrit Care 19, 199–205 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-013-9853-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-013-9853-y