Abstract

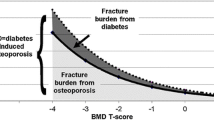

Measurement of bone mineral density (BMD) is underutilized, contributing to the underdiagnosis and undertreatment of osteoporosis. Appropriate patient selection for BMD testing leads to more people being treated, fewer fractures, and a decrease in fracture-related health care costs. Although there are well-established indications for BMD testing, it is less clear when a BMD test should be repeated for a patient who does not have osteoporosis and is found to be at low fracture risk with initial testing. BMD testing intervals should be individualized according to the likelihood that the results will influence treatment decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Gourlay ML, Fine JP, Preisser JS, et al. Bone-density testing interval and transition to osteoporosis in older women. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(3):225–33.

Looker AC, Melton LJ, III, Borrud LG, Shepherd JA: Changes in femur neck bone density in US adults between 1988-1994 and 2005-2008: demographic patterns and possible determinants. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(2):771–80.

Sornay-Rendu E, Munoz F, Garnero P, et al. Identification of osteopenic women at high risk of fracture: the OFELY study. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20(10):1813–9.

Nevitt MC, Ettinger B, Black DM, et al. The association of radiographically detected vertebral fractures with back pain and function: A prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128(10):793–800.

Black DM, Cummings SR, Genant HK, et al. Axial and appendicular bone density predict fractures in older women. J Bone Miner Res. 1992;7(6):633–8.

Baim S, Binkley N, Bilezikian JP, et al. Official positions of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry and executive summary of the 2007 ISCD Position Development Conference. J Clin Densitom. 2008;11(1):75–91.

National Osteoporosis Foundation: Clinician's Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Available at http://www.nof.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/NOF_ClinicianGuide2009_v7.pdf. Accessed August 2011.

Lewiecki EM, Binkley N, Petak SM. DXA quality matters. J Clin Densitom. 2006;9(4):388–92.

Frier A. Women too often tested for osteoporosis, researchers report. Available at http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-01-18/many-women-screened-for-osteoporosis-don-t-need-it-researchers-report.html. Accessed January 2012.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: recommendations and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(6):526–8.

ABC News: Osteoporosis tests unnecessary? Available at http://abcnews.go.com/WNT/video/osteoporosis-tests-unnecessary-15398771. Accessed April 2012.

Kolata G. Patients with normal bone density can delay retests, study suggests. Available at http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/19/health/bone-density-tests-for-osteoporosis-can-wait-study-says.html. Accessed January 2012.

Knox R. Many older women may not need frequent bone scans. Available at http://www.npr.org/blogs/health/2012/01/19/145419138/many-older-women-may-not-need-frequent-bone-scans?ps=sh_sthdl. Accessed January 2012.

Lewiecki EM, Laster AJ, Miller PD, Bilezikian JP. More bone density testing is needed, not less. J Bone Miner Res. 2012.

King AB, Fiorentino DM. Medicare payment cuts for osteoporosis testing reduced use despite tests' benefit in reducing fractures. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(12):2362–70.

United States Department of Health and Human Services: Payment for Bone Density Tests. Available at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2011-11-28/html/2011-28597.htm. Accessed April 2012.

The Lewin Group. Assessing the costs of performing DXA services in the office-based setting (survey data report prepared for American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. International Society for Clinical Densitometry, The Endocrine Society, and American College of Rheumatology). Available at https://www.aace.com/sites/default/files/DXAFinalReport.pdf. Accessed 2012.

Newman ED, Ayoub WT, Starkey RH, et al. Osteoporosis disease management in a rural health care population: hip fracture reduction and reduced costs in postmenopausal women after 5 years. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14(2):146–51.

Dell R, Greene D, Schelkun SR, Williams K. Osteoporosis disease management: the role of the orthopaedic surgeon. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90 Suppl 4:188–94.

Nayak S, Roberts MS, Greenspan SL. Cost-effectiveness of different screening strategies for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(11):751–61.

Lim LS, Hoeksema LJ, Sherin K. Screening for osteoporosis in the adult U.S. population: ACPM position statement on preventive practice. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(4):366–75.

Schousboe JT. Cost effectiveness of screen-and-treat strategies for low bone mineral density: how do we screen, who do we screen and who do we treat? Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2008;6(1):1–18.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Osteoporosis: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:356–64.

Lewiecki EM. Monitoring pharmacological therapy for osteoporosis. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2010;11(4):261–73.

Disclosure

Conflicts of interest: E.M. Lewiecki: has received financial support or owned personal investments in the following categories: Grant/research support (principal investigator, funding to New Mexico Clinical Research & Osteoporosis Center) for Amgen, Eli Lilly,

Merck, GlaxoSmithKline; Other support from Amgen (scientific advisory board, speakers’ bureau); Eli Lilly (scientific advisory board, speakers’ bureau); Novartis (speakers’ bureau); Merck (scientific advisory board); GlaxoSmithKline (consultant); and Warner Chilcott (speakers’ bureau); N. Binkley (Research support: Amgen, Lilly, Merck, Tarsa; Consultant: Lilly, Merck).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lewiecki, E.M., Binkley, N. Bone Density Testing Intervals and Common Sense. Curr Osteoporos Rep 10, 217–220 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11914-012-0111-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11914-012-0111-6