Abstract

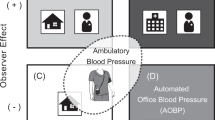

Guidelines for the diagnosis and monitoring of hypertension were historically based on in-office blood pressure measurements. However, the US Preventive Services Task Force recently expanded their recommendations on screening for hypertension to include out-of-office blood pressure measurements to confirm the diagnosis of hypertension. Out-of-office blood pressure monitoring modalities, including ambulatory blood pressure monitoring and home blood pressure monitoring, are important tools in distinguishing between normotension, masked hypertension, white-coat hypertension, and sustained (including uncontrolled or drug-resistant) hypertension. Compared to in-office readings, out-of-office blood pressures are a greater predictor of renal and cardiac morbidity and mortality. There are multiple barriers to the implementation of out-of-office blood pressure monitoring which need to be overcome in order to promote more widespread use of these modalities.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Egan BM, Zhao Y, Axon RN. US trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension, 1988–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(20):2043–50.

Lv J, Neal B, Ehteshami P, et al. Effects of intensive blood pressure lowering on cardiovascular and renal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9(8):e1001293.

Lv J, Ehteshami P, Sarnak MJ, et al. Effects of intensive blood pressure lowering on the progression of chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2013;185(11):949–57.

Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Effects of blood pressure lowering on outcome incidence in hypertension: 2. Effects at different baseline and achieved blood pressure levels—overview and meta-analyses of randomized trials. J Hypertens. 2014;32(12):2296–304.

USRDS 2014 Annual Data Report. 2014; http://www.usrds.org/2014/download/V2_Ch_01_ESRD_Incidence_Prevalence_14.pdf.

Sheridan S, Pignone M, Donahue K. Screening for high blood pressure: a review of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Am J Prev Med. 2003;25(2):151–8.

Wolff T, Miller T. Evidence for the reaffirmation of the U. S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation on screening for high blood pressure. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(11):787–U747.

Spruill TM, Feltheimer SD, Harlapur M, et al. Are there consequences of labeling patients with prehypertension? An experimental study of effects on blood pressure and quality of life. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74(5):433–8.

Viera AJ, Lingley K, Esserman D. Effects of labeling patients as prehypertensive. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(5):571–83.

Taylor DW, Haynes RB, Sackett DL, Gibson ES. Longterm follow-up of absenteeism among working men following the detection and treatment of their hypertension. Clin Invest Med. 1981;4(3–4):173–7.

Piper MA, Evans CV, Burda BU, Margolis KL, O’Connor E, Whitlock EP. Diagnostic and predictive accuracy of blood pressure screening methods with consideration of rescreening intervals: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(3):192–204.

Siu AL. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for high blood pressure in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(10):778–86. These recommendations, recently released by the US Preventive Services Task Force, introduce an addendum to the previous recommendations for screening of all adults age 18 years or older. The recommendations now advise obtaining out-of-office blood pressure measurements for the confirmation of hypertension before starting treatment.

Parati G, Stergiou GS, Asmar R, et al. European Society of Hypertension practice guidelines for home blood pressure monitoring. J Hum Hypertens. 2010;24(12):779–85.

Bloch MJ, Basile JN. UK guidelines call for routine 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in all patients to make the diagnosis of hypertension—not ready for prime time in the United States. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2011;13(12):871–2.

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2560–72.

James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507–20.

Handler J, Zhao Y, Egan BM. Impact of the number of blood pressure measurements on blood pressure classification in US adults: NHANES 1999–2008. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2012;14(11):751–9.

Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, Metoki H, et al. Prognosis of “masked” hypertension and “white-coat” hypertension detected by 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring 10-year follow-up from the Ohasama study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46(3):508–15.

Staessen JA, Thijs L, Fagard R, et al. Predicting cardiovascular risk using conventional vs ambulatory blood pressure in older patients with systolic hypertension. Jama-J Am Med Assoc. 1999;282(6):539–46.

Agarwal R, Andersen MJ. Prognostic importance of ambulatory blood pressure recordings in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2006;69(7):1175–80.

Agarwal R, Andersen MJ. Blood pressure recordings within and outside the clinic and cardiovascular events in chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol. 2006;26(5):503–10.

Pickering TG, Shimbo D, Haas D. Ambulatory blood-pressure monitoring. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(22):2368–74.

Hanninen MR, Niiranen TJ, Puukka PJ, Johansson J, Jula AM. Prognostic significance of masked and white-coat hypertension in the general population: the Finn-Home Study. J Hypertens. 2012;30(4):705–12.

Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, Falnker BE, Graves JW, Hill MN. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the subcommittee of professional and public education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation. 2005;111:697–716.

Peacock J, Diaz KM, Viera AJ, Schwartz JE, Shimbo D. Unmasking masked hypertension: prevalence, clinical implications, diagnosis, correlates and future directions. J Hum Hypertens. 2014;28(9):521–8.

Fagard RH, Cornelissen VA. Incidence of cardiovascular events in white-coat, masked and sustained hypertension versus true normotension: a meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2007;25(11):2193–8.

Hansen TW, Kikuya M, Thijs L, et al. Prognostic superiority of daytime ambulatory over conventional blood pressure in four populations: a meta-analysis of 7,030 individuals. J Hypertens. 2007;25(8):1554–64.

Stergiou GS, Asayama K, Thijs L, et al. Prognosis of white-coat and masked hypertension: International Database of Home blood pressure in relation to cardiovascular outcome. Hypertension. 2014;63(4):675–82. This large retrospective study of patients across five countries demonstrated a significantly increased hazards of adverse cardiovascular events in patients with untreated masked hypertension compared to untreated patients who were normotensive as well as in patients with treated masked hypertension compared to treated patients with controlled hypertension. The study also demonstrated a significantly increased hazard of adverse cardiovascular events and mortality among untreated patients with white-coat hypertension compared to untreated normotensive patients, but no increased hazard of adverse cardiovascular events or mortality among patients on antihypertensive medication who had white-coat effect compared to treated patients with controlled hypertension.

Diaz KM, Veerabhadrappa P, Brown MD, Whited MC, Dubbert PM, Hickson DA. Prevalence, determinants, and clinical significance of masked hypertension in a population-based sample of African Americans: the Jackson Heart Study. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28(7):900–8. This population-based study of African American patients living in the southern United States demonstrated a prevalence of masked hypertension of 34.4 % among study participants. Individuals with masked hypertension had significantly more advanced signs of target organ (i.e. renal and cardiovascular) damage than patients with sustained normotension.

Tientcheu D, Ayers C, Das SR, et al. Target organ complications and cardiovascular events associated with masked hypertension and white-coat hypertension: analysis from the Dallas Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(20):2159–69. This multiethnic, probability-based cohort of patients being followed for development of cardiovascular disease demonstrated a prevalence of 17.8 % of masked hypertension and of 3.3 % of white-coat hypertension among study participants. Patients with either white-coat hypertension or masked hypertension had a significantly higher rate of target organ damage as well as a greater hazard for cardiovascular events compared to normotensive patients.

Kanno A, Metoki H, Kikuya M, et al. Usefulness of assessing masked and white-coat hypertension by ambulatory blood pressure monitoring for determining prevalent risk of chronic kidney disease: the Ohasama study. Hypertens Res. 2010;33(11):1192–8.

Pogue V, Rahman M, Lipkowitz M, et al. Disparate estimates of hypertension control from ambulatory and clinic blood pressure measurements in hypertensive kidney disease. Hypertension. 2009;53(1):20–7.

Drawz PE, Alper AB, Anderson AH, et al. Masked hypertension and elevated nighttime blood pressure in CKD: prevalence and association with target organ damage. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(4):642–52. This analysis of patients with chronic kidney disease enrolled in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort demonstrated a 27.8 % prevalence of masked hypertension among study participants. Patients with masked hypertension had significantly more severe renal and cardiovascular target organ damage compared to normotensive subjects.

Pickering TG, Harshfield GA, Kleinert HD, Blank S, Laragh JH. Blood pressure during normal daily activities, sleep, and exercise. Comparison of values in normal and hypertensive subjects. JAMA. 1982;247(7):992–6.

Pickering TG, White WB, Group ASoHW. ASH position paper: home and ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. When and how to use self (home) and ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2008;10(11):850–5.

Parati G, Stergiou G, O’Brien E, et al. European Society of Hypertension practice guidelines for ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Hypertens. 2014;32(7):1359–66.

De la Sierra A. Advantages of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in assessing the efficacy of antihypertensive therapy. Cardiol Ther. 2015;4 Suppl 1:5–17.

Pickering TG, Miller NH, Ogedegbe G, et al. Call to action on use and reimbursement for home blood pressure monitoring: executive summary: a joint scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American Society of Hypertension, and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. Hypertension. 2008;52(1):1–9.

Krause T, Lovibond K, Caulfield M, McCormack T, Williams B, Development G. Guideline. Management of hypertension: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2011;343:d4891.

Ohkubo T, Hozawa A, Yamaguchi J, et al. Prognostic significance of the nocturnal decline in blood pressure in individuals with and without high 24-h blood pressure: the Ohasama study. J Hypertens. 2002;20(11):2183–9.

Farmer CK, Goldsmith DJ, Cox J, Dallyn P, Kingswood JC, Sharpstone P. An investigation of the effect of advancing uraemia, renal replacement therapy and renal transplantation on blood pressure diurnal variability. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12(11):2301–7.

Kotsis V, Stabouli S, Bouldin M, Low A, Toumanidis S, Zakopoulos N. Impact of obesity on 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure and hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;45(4):602–7.

Mojon A, Ayala DE, Pineiro L, et al. Comparison of ambulatory blood pressure parameters of hypertensive patients with and without chronic kidney disease. Chronobiol Int. 2013;30(1-2):145–58.

Yano Y, Bakris GL, Matsushita K, Hoshide S, Shimoda K, Kario K. Both chronic kidney disease and nocturnal blood pressure associate with strokes in the elderly. Am J Nephrol. 2013;38(3):195–203.

Turak O, Afsar B, Siriopol D, et al. Morning blood pressure surge as a predictor of development of chronic kidney disease. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18(5):444–8. This prospective study demonstrated that augmented morning blood pressure surge was associated with a significantly increased rate of incident chronic kidney disease among patients with essential hypertension.

Pierdomenico SD, Pierdomenico AM, Di Tommaso R, et al. Morning blood pressure surge, dipping, and risk of coronary events in elderly treated hypertensive patients. Am J Hypertens. 2016;29(1):39–45.

Pierdomenico SD, Pierdomenico AM, Cuccurullo F. Morning blood pressure surge, dipping, and risk of ischemic stroke in elderly patients treated for hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27(4):564–70.

Hansen TW, Thijs L, Li Y, et al. Prognostic value of reading-to-reading blood pressure variability over 24 hours in 8938 subjects from 11 populations. Hypertension. 2010;55(4):1049–57.

Kent ST, Shimbo D, Huang L, et al. Rates, amounts, and determinants of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring claim reimbursements among Medicare beneficiaries. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2014;8(12):898–908.

Andersen MJ, Khawandi W, Agarwal R. Home blood pressure monitoring in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45(6):994–1001.

Stergiou GS, Ntineri A, Kollias A, Ohkubo T, Imai Y, Parati G. Blood pressure variability assessed by home measurements: a systematic review. Hypertens Res. 2014;37(6):565–72.

Fonseca-Reyes S, de Alba-Garcia JG, Parra-Carrillo JZ, Paczka-Zapata JA. Effect of standard cuff on blood pressure readings in patients with obese arms. How frequent are arms of a ‘large circumference’? Blood Press Monit. 2003;8(3):101–6.

Shimbo D, Abdalla M, Falzon L, Townsend RR, Muntner P. Role of ambulatory and home blood pressure monitoring in clinical practice: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(9):691–700.

Alpert BS, Quinn D, Gallick D. Oscillometric blood pressure: a review for clinicians. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2014;8(12):930–8.

Kallem RR, Meyers KE, Sawinski DL, Townsend RR. A comparison of two ambulatory blood pressure monitors worn at the same time. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2013;15(5):321–5.

Myers MG, Godwin M, Dawes M, et al. Conventional versus automated measurement of blood pressure in primary care patients with systolic hypertension: randomised parallel design controlled trial. Brit Med J. 2011;342.

Leung AA, Nerenberg K, Daskalopoulou SS, et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2016 Canadian hypertension education program guidelines for blood pressure measurement, diagnosis, assessment of risk, prevention, and treatment of hypertension. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32(5):569–88.

Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Kiss A. Use of automated office blood pressure measurement to reduce the white coat response. J Hypertens. 2009;27(2):280–6.

Lazaridis AA, Sarafidis PA, Ruilope LM. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in the diagnosis, prognosis, and management of resistant hypertension: still a matter of our resistance? Curr Hypertens Rep. 2015;17(10):78.

Rios MT, Dominguez-Sardina M, Ayala DE, et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of isolated-office and true resistant hypertension determined by ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Chronobiol Int. 2013;30(1-2):207–20.

Brambilla G, Bombelli M, Seravalle G, et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of patients with true resistant hypertension in central and Eastern Europe: data from the BP-CARE study. J Hypertens. 2013;31(10):2018–24.

de la Sierra A, Banegas JR, Segura J, Gorostidi M, Ruilope LM, Investigators CE. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring and development of cardiovascular events in high-risk patients included in the Spanish ABPM registry: the CARDIORISC Event study. J Hypertens. 2012;30(4):713–9.

Pierdomenico SD, Lapenna D, Bucci A, et al. Cardiovascular outcome in treated hypertensive patients with responder, masked, false resistant, and true resistant hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18(11):1422–8.

Burnier M, Wuerzner G. Ambulatory blood pressure and adherence monitoring: diagnosing pseudoresistant hypertension. Semin Nephrol. 2014;34(5):498–505.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Jordana B. Cohen and Debbie L. Cohen declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Hypertension

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cohen, J.B., Cohen, D.L. Integrating Out-of-Office Blood Pressure in the Diagnosis and Management of Hypertension. Curr Cardiol Rep 18, 112 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-016-0780-3

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-016-0780-3