Abstract

Jatropha curcas is considered a potential biodiesel feedstock crop. Currently, the value of J. curcas is limited because its seed yield is generally low. Transgenic modification is a promising approach to improve the seed yield of J. curcas. Although Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of J. curcas has been pursued for several years, the transformation efficiency remains unsatisfying. Therefore, a highly efficient and simple Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation method for J. curcas should be developed. We examined and optimized several key factors that affect genetic transformation of J. curcas in this study. The results showed that the EHA105 strain was superior to the other three Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains for infecting J. curcas cotyledons, and the supplementation of 100 mM acetosyringone slightly increased the transient transformation frequency. Use of the appropriate inoculation method, optimal kanamycin concentration and appropriate duration of delayed selection also improved the efficiency of stable genetic transformation of J. curcas. The percentage of β-glucuronidase positive J. curcas shoots reached as high as 56.0 %, and 1.70 transformants per explant were obtained with this protocol. Furthermore, we optimized the root-inducing medium to achieve a rooting rate of 84.9 %. Stable integration of the T-DNA into the genomes of putative transgenic lines was confirmed by PCR and Southern blot analysis. Using this improved protocol, a large number of transgenic J. curcas plantlets can be routinely obtained within approximately 4 months. The detailed information provided here for each step of J. curcas transformation should enable successful implementation of this transgenic technology in other laboratories.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With the decreasing supplies of fossil fuels and the worsening of environmental pollution, biodiesel has received increasing attention as an alternative fuel. Jatropha curcas is considered a potential oilseed crop for biofuel production because its seeds contain up to 40 % oil, which can be easily converted to biodiesel or bio-jet fuel and used to partially or fully replace fossil fuel (Fairless 2007; Juan et al. 2011; Makkar and Becker 2009). In addition, J. curcas can grow under climate and soil conditions that are unsuitable for food production (Maghuly and Laimer 2013), and it is a renewable feedstock for producing soap, green fertilizers, pesticides and medicines (Kumar and Sharma 2008). However, at present, J. curcas does not contribute to the biofuel industry because the yield of its seeds is generally low in many areas, and the investment in large-scale cultivation of J. curcas had moved ahead of the scientific studies aiming to fully explore this plant and understand its limitations (Sanderson 2009).

Breeding of varieties that produce high and stable yields is one of the most efficient approaches to making J. curcas into a successful biofuel crop. Because of the low genetic diversity of J. curcas (Rosado et al. 2010; Sun et al. 2008), conventional breeding technology has limited potential for use in the genetic improvement of this plant (Sujatha et al. 2008). Transgenic breeding techniques can complement conventional breeding technology and have many advantages, such as directional cultivation of new breeds, reduced costs, a shorter breeding period, and the ability to introduce genes for traits that may not be available within the species or may be difficult to introduce via conventional breeding methods (Herr and Carlson 2013; Li et al. 1996; Visarada et al. 2009). Moreover, with the completion of genomic sequencing analysis (Hirakawa et al. 2012; Sato et al. 2011), expressed sequence tag analysis (Chen et al. 2011; Eswaran et al. 2012; Natarajan et al. 2010), and transcriptomic studies (Costa et al. 2010; Natarajan and Parani 2011; Zhang et al. 2014), J. curcas is poised to become a new model woody plant. Genetic transformation may become an important method for molecular breeding and gene function analysis of J. curcas.

The efficiency of the in vitro plant regeneration system, the efficiency of Agrobacterium tumefaciens transformation, and the specific antibiotic selection procedure are key factors in plant genetic transformation (Kajikawa et al. 2012; Li et al. 2008; Mao et al. 2009). To date, shoot regeneration systems for J. curcas have been successfully established using various explants such as cotyledons, epicotyls, hypocotyls, leaves, petioles, nodes, and stems (Khurana-Kaul et al. 2010; Kumar and Reddy 2010; Sharma et al. 2011; Singh et al. 2010; Sujatha and Mukta 1996; Toppo et al. 2012). Some regeneration systems have been utilized in genetic transformation protocols employing A. tumefaciens (Khemkladngoen et al. 2011; Kumar et al. 2010; Li et al. 2008; Mao et al. 2009; Misra et al. 2012; Pan et al. 2010) or particle bombardment (Joshi et al. 2011; Purkayastha et al. 2010). Due to several advantages of Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation, including the defined integration of transgenes, potentially low copy number, and preferential integration into transcriptionally active regions of the chromosome (Newell 2000), this method is the most widely used to generate transgenic J. curcas. Several A. tumefaciens strains have been used in the genetic transformation of J. curcas, including LBA4404 (Kumar et al. 2010; Li et al. 2008; Misra et al. 2012), EHA105 (He et al. 2009; Jaganath et al. 2014; Mazumdar et al. 2010), GV3101 (Qin et al. 2014), and AGL1 (Mao et al. 2009). The types of selectable markers and the selection pressure also play important roles in the genetic transformation of different explants. Using the herbicide phosphinothricin as a selective agent, Li et al. (2008) first reported the generation of transgenic J. curcas. Thereafter, several groups found that transgenic J. curcas can be regenerated by selection using hygromycin (Joshi et al. 2011; Kumar et al. 2010; Mao et al. 2009), kanamycin (Khemkladngoen et al. 2011; Misra et al. 2012; Pan et al. 2010), or bispyribac-sodium salt (Kajikawa et al. 2012). Many protocols required multiple handling steps and frequent changes of different medium, which not only require additional time but also may introduce contamination. The regeneration of transformed shoots takes 4–7 months, and the transformation efficiency is 4–53 % (Kajikawa et al. 2012; Khemkladngoen et al. 2011; Kumar et al. 2010; Li et al. 2008; Misra et al. 2012). Therefore, a simple, highly efficient, and rapid Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation system for J. curcas should be developed. Notably, root induction of regenerated shoots is also an important step for obtaining transgenic plants. Several root-inducing mediums (RIM) have been successfully used in the root induction of regenerated J. curcas shoots, but the rooting efficiency varied greatly, from 16 to 86 % in 1/2 MS medium supplemented with 0.2–0.5 mg L−1 IBA (Kajikawa et al. 2012; Khemkladngoen et al. 2011; Li et al. 2008; Toppo et al. 2012). Mazumdar et al. (2010) reported that the rooting induction efficiency of the J. curcas shoots was 75 % in 1/2 MS containing 5.0 μM (0.9 mg L−1) NAA within 17–20 days of cultivation. So RIM should also be optimized to ensure high and stable rooting efficiency of transformed shoots.

We have previously developed a simple and efficient Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation system for J. curcas using the cotyledons from mature seeds as explants (Pan et al. 2010). In this simple protocol, all stages of cultivation, including co-cultivation, callus initiation and proliferation, selection of transgenic calli, and regeneration of shoots, were performed on a single medium (MS-Jc1: MS medium supplemented with 3 mg L−1 BA and 0.01 mg L−1 IBA) with different antibiotics (Pan et al. 2010). However, the transformation efficiency of this method is low and variable (Kajikawa et al. 2012); thus, it requires substantial improvement.

In the present study, we further improved the protocol described previously by Pan et al. (2010) by optimizing several key factors including the supplementation of acetosyringone (AS), selection of A. tumefaciens strains, scheme of transformant selection, determination of antibiotic selection pressure, and formulation of RIM. This improved protocol substantially increases the regeneration efficiency of transgenic J. curcas; the percentage of β-glucuronidase (GUS)-positive shoots reached an average of 56.0, and 84.9 % of the transgenic shoots successfully rooted. Moreover, this protocol includes additional details that were not previously described by Pan et al. (2010).

Materials and methods

Preparation of explants

Mature J. curcas L. seeds were collected from trees grown in Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden (21°54′N, 101°46′E, 580 m asl) at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, located in Mengla County, Yunnan Province, China. The husked seeds were soaked in sterile water for 10–12 h at room temperature. The seeds were then surface sterilized with 75 % (v/v) ethanol for 1 min, followed by soaking for 15 min in 1.1 % (w/v) sodium hypochlorite and 0.1 % (v/v) Tween-20 with occasional agitation. Subsequently, the seeds were rinsed three times with sterile distilled water. The sterilized seeds were carefully dissected with a scalpel, and the embryos were removed from the seeds. Approximately 3/4 of the papery cotyledons were excised by cutting off the base of the cotyledons and the embryo axes, as shown in Pan et al. (2010). These cotyledons were used as explants for Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation.

Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains and vector used for transformation

The A. tumefaciens strains LBA4404, EHA105, GV3101, and AGL1, all of which harbor the binary vector pCAMBIA2301 (CAMBIA, Canberra, Australia), were used for transformation experiments. EHA105 carrying 35S:AtFT was used to evaluate the transformation method in subsequent transformation experiments. A single colony of A. tumefaciens was inoculated into 5 mL of liquid yeast extract and beef (YEB) medium containing 50 mg L−1 kanamycin and 25 mg L−1 streptomycin or 50 mg L−1 rifampicin and grown overnight at 28 °C on a rotary shaker at 200 rpm. An aliquot (0.5 mL) of the overnight culture was inoculated into 50 mL of liquid YEB medium containing the same antibiotics and allowed to grow at 28 °C with vigorous shaking until the OD600 reached approximately 0.6–1.0. A. tumefaciens cells were then collected by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C and re-suspended at OD600 = 0.4 with liquid Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium (Murashige and Skoog 1962) supplemented with 100 μM AS. The bacterial suspension was allowed to stand for approximately an hour before use.

Transformation, selection, and regeneration of transformants

The excised cotyledon explants were inoculated with the A. tumefaciens suspension by co-incubation with shaking on a rotary shaker for 20 min at 150 rpm. The temperature was maintained at 28 °C. The explants were then transferred onto sterile filter paper to remove excess A. tumefaciens before being cultured on co-cultivation medium (CCM: MS-Jc1 supplemented with 100 μM AS) for 3 days at 26 ± 2 °C in the dark. Following co-cultivation, the explants were washed three times with sterile water containing 500 mg L−1 cefotaxime to eliminate A. tumefaciens and blotted dry on sterile filter paper. Then, they were transferred initially to callus-inducing medium [CIM: MS-Jc1 supplemented with 300 mg L−1 cefotaxime and 100 mg L−1 ticarcillin and clavulanate potassium (timentin)] for callus initiation and growth and subsequently cultured for 1, 2, or 3 weeks (Table 1). The explants were cultured under a 14 h light/10 h dark cycle with fluorescent light (100 μ Em−2 s−1) at 26 ± 2 °C. Then, the swollen cotyledon explants with small calli were placed on shoot-inducing medium (SIM: MS-Jc1 supplemented with 300 mg L−1 cefotaxime, 100 mg L−1 timentin, and 20, 30, or 40 mg L−1 kanamycin) with 1 cm of the cut end of each cotyledon inserted into the medium. After the 3-week culture period, the explants were individually subcultured to fresh SIM. Resistant calli and shoots were subcultured at 3-week intervals. The number of shoots per explant, frequency of positive GUS staining and transgene incorporation were scored after 12 weeks of cultivation on SIM.

Rooting and acclimation

Green and healthy regenerated shoots with three to four leaves were excised and transferred to root-inducing medium (RIM: half-strength (1/2) MS medium supplemented with 100 mg L−1 timentin, 1.0 % sucrose, 0.25 % carrageenan, and different combinations of IBA and NAA) (Table 2). The percentage of root induction was recorded and evaluated after 4 weeks and was calculated by comparing the number of rooting shoots to the total number of shoots. Rooted plantlets were carefully removed from the medium, washed thoroughly in running water to remove RIM attached to the roots, soaked in 0.1 % w/v carbendazim for 2 h, and then planted in polythene cups filled with sterilized soil consisting of humus:peat:vermiculite (3:1:1), covered with transparent plastic film to maintain humidity, and grown in the greenhouse at 22 ± 2 °C under a 16/8 h (light/dark) photoperiod with fluorescent light (100 μ Em−2 s−1). After 2 weeks, the transparent plastic film was removed, and the plants were sprayed with water to avoid wilting of the leaves in the first 2 days. The number of surviving plants was recorded after an additional 1–2 weeks.

Molecular analysis of transgenic plantlets

Genomic DNA was isolated from the leaves of putative transgenic plants and controls using the cetyl trimethylammonium bromide method (Allen et al. 2006). PCR analysis of the isolated genomic DNA was performed to identify transgenes in putative transformants using primers (Table S1) for the GUS and NPTII genes. A 35S CaMV promoter primer and a GUS-specific primer were used to detect the GUS gene, which produced a 778-bp fragment. The NPTII gene was amplified with the NPTII-specific primer pair, producing a 679-bp fragment. PCR amplification reactions were performed in a 20-μL volume, and the PCR parameters were as follows: 94 °C for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 61 °C (for GUS)/58 °C (for NPTII) for 30 s and 72 °C for 1 min with a final extension of 10 min at 72 °C. The plasmid pCAMBIA2301 was used as a positive control, and non-transgenic plant DNA was used as a negative control. PCR amplification products were separated on 1.0 % (w/v) agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining under UV light.

For Southern blot analysis, 5 µg of genomic DNA from the PCR-positive leaves was digested with EcoRI and XhoI (EcoRI and XhoI cut the pCAMBIA2301 plasmid once outside of the GUS gene) overnight at 37 °C to cleave a unique site in the T-DNA. Following digestion, the DNA fragments were separated on 0.8 % (w/v) agarose gels, which were then processed and transferred to Hybond-N+ membranes (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) following the standard procedure (Sambrook et al. 2001). The 483-bp fragment of the GUS probe was labeled with digoxigenin (DIG) using a Roche PCR DIG Probe Synthesis Kit. Hybridization and chemiluminescent detection of the blots were performed following the manufacturer’s instructions (Roche). Total RNA of 35S:AtFT transgenic lines and controls was extracted from frozen tissue as described by Ding et al. (Ding et al. 2008). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript® RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (TAKARA, Dalian, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The primers used for RT-PCR are listed in Table S1.

Histochemical staining of β-glucuronidase (GUS) activity

Histochemical staining of GUS activity was performed according to the method of Jefferson et al. (1987) with some modifications. Transient GUS expression in cotyledon explants was monitored at 3 days after A. tumefaciens transformation, and stable GUS expression was examined in kanamycin-resistant calli, leaf lamina of positive shoots, stems, roots, flowers, young fruits of putative T0 transgenic adult plants, T1 cotyledons from GUS-positive plants, and the same tissues of the control plants. These samples were immersed in GUS staining solution (50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0), 0.5 mM K3Fe(CN)6, 0.5 mM K4Fe(CN)6·3H2O, 0.5 % Triton X-100 and 1 mM X-gluc) and subjected to vacuum for 20 min. After incubation in the GUS staining solution at 37 °C overnight, the samples were destained in 70 % ethanol for several hours to visualize the GUS-stained areas. The efficiency of transient transformation was calculated by comparing the number of GUS-stained cotyledons to the total number of cotyledons infected by A. tumefaciens. The percentage of GUS-positive shoots was calculated by comparing the number of GUS-stained leaves to the total number of leaves from kanamycin-resistant shoots.

Statistical analysis

In this study, 30–50 explants were used for each experimental condition, and each experiment was repeated three times. The efficiency of transient transformation, the percentage of GUS-positive shoots and root induction were analyzed using the Statistical Product and Service Solution software (version 16.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and the data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the repeated experiments. Analysis of variance among the means was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test.

Results

Influence of AS and A. tumefaciens strains on the efficiency of transient transformation

To determine the effects of AS on the transformation efficiency of cotyledon explants of J. curcas infected with A. tumefaciens, the efficiency of transient transformation was analyzed by examining the GUS-stained cotyledons after 3 days of co-cultivation with A. tumefaciens. The addition of 100 mM AS during infection and co-cultivation slightly increased the transient transformation efficiency from 84 to 92 % using EHA105, and from 48 to 54 % using LBA4404, respectively (Fig. 1a). Therefore, 100 mM AS was used in the subsequent infection and co-cultivation experiments. To select the best A. tumefaciens strain for J. curcas transgenic studies, the transformation efficiencies of four A. tumefaciens strains harboring pCAMBIA2301—EHA105, LBA4404, GV3101, and AGL1—were examined. As shown in Fig. 1b, different A. tumefaciens strains exhibited significant differences in their ability to transform cotyledon explants of J. curcas. Compared with the other A. tumefaciens strains, EHA105 showed the highest transient transformation efficiency (92 %). The transient transformation efficiencies of LBA4404, GV3101, and AGL1 were approximately 54, 19 and 14 %, respectively (Fig. 1b). An intense blue color was observed in the incisions in cotyledons (Fig. 1c). The number of stained areas per EHA105-infected explant was significantly higher than that observed with other A. tumefaciens strains, whereas no GUS staining was detected in control explants transformed with EHA105 without the binary vector (Fig. 1c). Therefore, EHA105 was superior to the other three A. tumefaciens strains for infecting J. curcas cotyledons, and was selected for subsequent transformation experiments in this study.

Efficiency of transient transformation of J. curcas cotyledon explants after 3 days of co-cultivation with Agrobacterium tumefaciens. a Influence of AS on the efficiency of transient transformation. b Influence of Agrobacterium strains on the efficiency of transient transformation. c Transient GUS expression differed in the incisions of cotyledons after co-cultivation with different Agrobacterium strains. Each value is the mean ± SE of three independent experiments, each including 30 cotyledons. Values with different lowercase letters are significantly different (P < 0.05, Tukey’s test). Values with different uppercase letters are significantly different (P < 0.01, Tukey’s test). Red arrows indicate GUS staining on cotyledon explants

Optimization of kanamycin concentration and duration of delayed selection

As shown in our previous report of J. curcas transformation, cotyledon explants excised from mature seeds of J. curcas were very sensitive to the selection agent kanamycin, and 5 mg L−1 kanamycin in the medium completely inhibited callus formation from cotyledon explants (Pan et al. 2010). The regeneration frequency and positive transformation rate were relatively low when cotyledon explants were cultivated on CIM without kanamycin for 4 weeks after co-cultivation with Agrobacterium (Pan et al. 2010). To improve the efficiency of kanamycin selection in J. curcas, nine independent selection experiments were carried out with different kanamycin concentrations and duration of delayed selection (Table 1). After co-cultivation with A. tumefaciens, the cotyledon explants were then transferred onto CIM and cultured for 1, 2, or 3 weeks without selection. The cotyledon explants began to turn green and grow larger after 1 week (Fig. 2a), and some small calli were produced on the cut ends of the swollen cotyledon explants. The cotyledon explants were inserted into the SIM with the cut ends embedded in the medium (Fig. 2b). A clear difference was observed between the transformed and untransformed cotyledon explants during the kanamycin selection process: there were many green calli formed at the incisions of the transformed cotyledon explants (Additional file 1: Fig. S1 a and c), whereas no such resistant calli were formed from the untransformed cotyledon explants (Additional file 1: Fig. S1 b and d). The base of cotyledon explants embedded in the medium turned yellow, and they gradually formed many resistant calli at the incisions after 3 weeks under the condition of 1-week delayed selection with 40 mg L−1 kanamycin, whereas the upper section of cotyledon explants (above the medium) stayed green and continued to grow (Fig. 2c, d). Then, the resistant calli were excised and transferred onto new SIM for the second cycle of selection; during this period, some adventitious buds were found in the regions of the resistant calli. Resistant calli and shoots were subcultured at 3-week intervals. After three passages of selection, many resistant shoots were regenerated, as shown in Fig. 2e. Additional adventitious shoots were obtained during the fourth selection cycle. Resistant shoots that were 1.5–2 cm in length with 3–4 leaves were excised and cultured on RIM for inducing roots (Fig. 2f).

Different stages of Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of J. curcas. a Swollen cotyledon explants incubated on CIM for 1 week. b Inserting cotyledon explants into SIM after cultivation on CIM for 7 days to induce resistant calli. c Three-week-old resistant calli in SIM under the condition of 1-week delayed selection with 40 mg L−1 kanamycin. d Resistant calli (indicated by red arrows) in SIM. e Resistant shoot buds on SIM under the condition of 1-week delayed selection with 40 mg L−1 kanamycin in the third cycle of selection. f Resistant plantlets were excised and transferred to RIM. g Putative transgenic plantlets rooted after incubation on RIM for 4 weeks. h Transgenic plants in pots acclimatized in the greenhouse for 4 weeks. i Growth of transgenic plantlets in the field. Scale bars represent 5 mm

We utilized GUS staining as an indicator of successful transformation, and the GUS expression rate was calculated as follows: GUS-positive shoots/total kanamycin-resistant shoots (Table 1). The number of shoots per explant was measured to calculate the regeneration frequency. The regenerated shoots from the third and fourth cycles of kanamycin selection were statistically analyzed, and the leaves of these regenerated shoots were examined by GUS staining. As shown in Table 1, the regeneration frequency of shoots decreased significantly as the kanamycin concentration and the duration of delayed selection after co-cultivation increased. The highest regeneration frequency (5.56 shoots per explant) was observed under the condition of 1-week delayed selection with 20 mg L−1 kanamycin, whereas the lowest regeneration frequency (1.88 shoots per explant) was observed under the condition of 3-week delayed selection with 40 mg L−1 kanamycin (Table 1). More importantly, significant differences in the number of GUS-positive shoots per explant and the frequency of GUS-positive shoots were observed among different kanamycin concentrations and duration of delayed selection. The number of GUS-positive shoots per explant and the frequency of GUS-positive shoots were only 0.05 and 1.3 %, respectively, under the condition of a 3-week delayed selection with 20 mg L−1 kanamycin. When the kanamycin concentration was increased and the duration of delayed selection was reduced, the number of GUS-positive shoots per explant and the frequency of GUS-positive shoots increased gradually. Under the condition of a 1-week delayed selection with 40 mg L−1 kanamycin, the number of GUS-positive shoots per explant and the frequency of GUS-positive shoots reached maxima of 1.70 and 56.0 %, respectively (Table 1).

Optimization of the root-inducing medium

To obtain high rooting efficiency, we optimized RIM used for root induction from regenerated shoots by adding different concentrations of IBA and NAA to 1/2 MS. As shown in Table 2, the rooting frequency increased with increases in the concentrations of IBA or NAA. The lowest rooting frequency was observed on 1/2 MS basal medium, only 5.8 %. A rooting frequency of approximately 65.0 % was observed on RIM with 0.2 mg L−1 NAA. The combination of 0.2 mg L−1 IBA and 0.1 mg L−1 NAA in RIM further increased the rooting percentage to its highest value (84.9 %) (Table 2). Adventitious roots were initiated on regenerated shoots incubated on RIM within 2 weeks, and the roots were much more numerous and stronger after incubation on RIM for 4 weeks (Fig. 2g). Rooted plantlets were planted in sterilized soil consisting of humus:peat:vermiculite (3:1:1) and acclimatized in the greenhouse at 22 ± 2 °C. After 4–5 weeks, more than 85 % of the acclimatized plantlets survived, and there was no obvious phenotypic difference among GUS transgenic J. curcas plants (Fig. 2h). Then, the plantlets were transferred to the fields for further growth (Fig. 2i).

Confirmation of transgenic plants

To confirm the presence of the transgenes in the putative transgenic plants, genomic DNA was extracted from the leaves of non-transformed and putative transgenic plants in pots, which were selected with 40 mg L−1 kanamycin after cultivation on CIM for 1 week. Then, the reporter gene GUS and the selective marker gene NPTII were identified by PCR amplification. A 778-bp fragment corresponding to the GUS gene was detected in most of the putative transgenic plants (Fig. 3a, upper panel, lanes 1 – 10) and the positive control (Fig. 3a, upper panel, lane P), but no amplification product was found in the non-transformed control plant (Fig. 3a, upper panel, lane C). The expected 679-bp fragment of the NPTII gene was also detected in most of the putative transgenic plants (Fig. 3a, lower panel, lanes 1–10), whereas the control plant showed no amplification products (Fig. 3a, lower panel, lane C).

PCR and Southern blot analysis of transgenic J. curcas plants. a Amplification of the 778-bp GUS gene (upper panel) and the 679-bp NPTII gene (lower panel) in transgenic plants. Lanes: M, molecular size marker (Trans2 K DNA ladder); P, positive control (pCAMBIA2301 plasmid); C, negative control (non-transformed plant); 1–10, putative transgenic J. curcas lines. b Southern hybridization of genomic DNA isolated from negative control (a non-transformed plant) and PCR-positive shoots. Genomic DNA was digested with EcoRI and hybridized with a DIG-labeled GUS probe. Lanes: C, negative control (a non-transformed plant); 2, 3, 7, 8, and 9, five independent transgenic plants

The integration of the GUS gene into the genome of transgenic J. curcas plants was further verified by Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA from PCR-positive transgenic plants. As shown in Fig. 3b, all of the tested plants showed one band after hybridization (Fig. 3b, lanes 2, 3, 7, 8 and 9), and no hybridization band was detected when control plant DNA was used (Fig. 3b, lane C). This result indicates that a single copy of the GUS gene had integrated into the genomes of the tested transgenic plants.

GUS histochemical analysis

The stable transformation events were further monitored using histochemical analysis of GUS activity. As shown in Fig. 4a and b, intense blue staining was visibly detected in a resistant callus and young leaf from a regenerated shoot under the condition of 1-week delayed selection with 40 mg L−1 kanamycin, whereas no such blue staining was detected in a non-transformed callus and leaf (control) (Fig. 4h, i). To visualize stable GUS expression in adult transgenic plants, we next analyzed the stems, roots, flowers, and fruits. Strong GUS staining was observed in the stems, roots, flowers and fruits of T0 adult transgenic plants (Fig. 4c–f), whereas no GUS expression was observed in the negative control plants (Fig. 4j–m). Positive GUS expression was also observed in cotyledons of the progeny (T1) of transgenic plants (Fig. 4g), whereas GUS activity was not detected in the cotyledons of the control plants (Fig. 4n), indicating that the transgene was stably inherited in T1 progeny.

Histochemical GUS staining of various tissues of transgenic J. curcas Representative photos of GUS-stained calli (a and h), leaves (b and i), stems (c and j), roots (d and k), flowers (e and l), and fruits (f and m) from T0 transgenic plants (a-f) and control (h-m). Cotyledons from the progeny (T1) of transgenic (g) and control (n) plants are also shown. Scale bars represent 5 mm

Overexpression of Arabidopsis FLOWERING LOCUS T in J. curcas causes early flowering in vitro

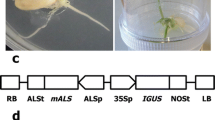

FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) is a key gene mediating the vegetative-to-reproductive transition and is conserved in many flowering plants (Kardailsky et al. 1999; Li et al. 2014; Ye et al. 2014). Using the transformation protocol described above, we transferred Arabidopsis FT (AtFT) cDNA under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter into 30 cotyledon explants of J. curcas, and we obtained a total of 17 independent transgenic shoots in 2.5 months. Flower buds formed directly on most of the 35S:AtFT transgenic shoots of J. curcas in vitro, whereas the control explants did not produce flower buds under the same conditions (Fig. 5a, b). Semi-quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) analysis of gene expression related to flower bud development in J. curcas was performed on the shoot apexes of the wild-type (WT) and 35S:AtFT transgenic lines cultured in vitro. Consistent with the phenotype of the transgenic shoots, which showed early flowering in vitro, the transcript levels of AtFT, JcSOC1, JcLFY, JcAP1and JcAP3 were significantly upregulated in the transgenic lines (Fig. 5c). These results demonstrate that the improved transformation protocol provides a reliable method for the introduction of functional genes into J. curcas.

Phenotypes of WT and 35S:AtFT transgenic J. curcas shoots cultured in vitro and semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis of flowering genes in these lines. a WT J. curcas shoot cultured in vitro. b Flower buds of 35S:AtFT transgenic J. curcas cultured in vitro. c Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis of flowering genes in the shoot apexes of WT and 35S:AtFT transgenic J. curcas cultured in vitro. Red arrows indicate flower buds. Scale bars represent 1 cm

Discussion

As a potent inducer of A. tumefaciens for infecting plant cells, AS has been successfully employed to improve transformation efficiency in many plants (Bull et al. 2009; Ramamoorthy and Kumar 2012; Wang et al. 2012). Similar to the results obtained by Li et al. (2008) and Kumar et al. (2010), the addition of 100 mM AS in this study slightly enhanced GUS transient expression efficiency in J. curcas compared with the control (Fig. 1a). The A. tumefaciens strain is one of the most important factors potentially affecting the efficiency of genetic transformation. Different Agrobacterium strains have been successfully used to transform J. curcas; however, the transformation efficiency varied greatly among the different transformation methods (Jaganath et al. 2014; Kajikawa et al. 2012; Li et al. 2008). We found that EHA105 was superior to other Agrobacterium strains for genetic transformation of J. curcas cotyledons (Fig. 1b, c). Our Southern blot analysis showed that the 5 transgenic J. curcas lines that we tested each had a single copy of the transgene (Fig. 3b), which is consistent with the report that Agrobacterium strain EHA105 appeared to be capable of generating single-copy transgenic tomato plants (Chetty et al. 2013).

The in vitro regeneration ability of the explants is crucial for establishing a successful Agrobacterium-mediated transformation system. Different explants of J. curcas have been reported to be used in transformation (Kajikawa et al. 2012; Khemkladngoen et al. 2011; Kumar et al. 2010; Li et al. 2008; Mao et al. 2009; Misra et al. 2012; Pan et al. 2010). In many plants, cotyledon explants are better suited to regeneration and transformation than other explants (Li et al. 2008, 2006; Murthy et al. 2003). Cotyledons excised from mature seeds of J. curcas, which are available in large quantities for transformation year-round, were found susceptible to A. tumefaciens infection (Li et al. 2014; Pan et al. 2010; Tao et al. 2015). In the current study, multiple resistant calli could be rapidly induced from the cut edges of cotyledon explants after 2–3 weeks of incubation on SIM (Fig. 2c), and transgenic shoots were regenerated from these resistant calli (Fig. 2e).

The selection strategy is also a key factor in improving transformation efficiency. Many plant species, including J. curcas, have been found to be hypersensitive to kanamycin, and this hypersensitivity is most likely the source of the reduced transformation efficiencies observed in previous studies (Kajikawa et al. 2012; Pan et al. 2010). Alternative selection strategies, including reduced kanamycin concentrations and delayed selection, have been successful for obtaining transgenic plants in kanamycin–hypersensitive species, including apple (Yao et al. 1995) and almond (Miguel and Oliveira 1999; Ramesh et al. 2006). In this study, with increasing kanamycin concentrations and decreasing durations of delayed selection, the number of GUS-positive shoots increased (Table 1). A stable transformation rate of approximately 56.0 % and 1.70 GUS-positive shoots per explant were obtained under the condition of 1-week delayed selection with 40 mg L−1 kanamycin (Table 1). The success of selection depends not only on kanamycin concentrations and delayed selection but also on improving the contact between explants and medium during inoculation (Bhatia et al. 2005). The cotyledon explants transferred from CIM were inserted into SIM with approximately 1 cm of their cut ends embedded in the medium (Fig. 2b). After 2–3 weeks, green calli and adventitious buds developed at the cut ends of cotyledon explants in the medium (Fig. 2c, d). This improved inoculation method might also result in a reduced number of escapees from kanamycin selection. To our knowledge, this is the first report describing the insertion of cut ends of explants into selection medium during Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of J. curcas.

We found that the rooting efficiency of regenerated J. curcas shoots varied greatly among different RIMs, which agrees with previous studies (Kajikawa et al. 2012; Khemkladngoen et al. 2011; Li et al. 2008; Mazumdar et al. 2010). The differences in rooting efficiency might depend not only on the concentrations of IBA and NAA in RIMs but also on the condition of shoots and/or the hormone levels in SIMs in these reports. Using different combinations of IBA and NAA, we optimized the conditions for root induction of the regenerated shoots. The highest rooting efficiency (84.9 %) was observed in 1/2 MS supplemented with 0.2 mg L−1 IBA and 0.1 mg L−1 NAA (Table 2). For the regenerated shoots that are difficult to root, in vivo grafting could be employed to obtain transgenic J. curcas plants (Jaganath et al. 2014; Li et al. 2014). In addition, transgenic J. curcas shoots overexpressing AtFT driven by the strong constitutive 35S promoter, which were obtained in this study and produced flower buds in vitro (Fig. 5b), were not able to develop into normal plants. As we showed previously with J. curcas FT homolog (Li et al. 2014), the use of weaker constitutive promoters, tissue specific promoters, or inducible promoters will be required to produce normal transgenic J. curcas plants overexpressing AtFT.

In conclusion, several important factors that affect the efficiency of Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of J. curcas were optimized in this study, including the supplementation of AS, A. tumefaciens strain, kanamycin concentration, duration of delayed selection, inoculation method, and root-inducing medium, which have not been tested in our previous study (Pan et al. 2010). Compared to our previous protocol, genetic transformation and rooting efficiency of the improved protocol were greatly enhanced and reached an average of 56.0 and 84.9 %, respectively. The overall scheme is presented in Fig. 6. The protocol requires only two basal media and takes approximately 4 months from the start of co-cultivation to the rooting of plantlets. This improved transformation protocol is simple and reproducible; thus, it may be useful for studies of functional genes and genetic improvement of J. curcas. And the genetic transformation strategy reported here may be applied to other plants with various selective agents and explant types.

References

Allen GC, Flores-Vergara MA, Krasnyanski S, Kumar S, Thompson WF (2006) A modified protocol for rapid DNA isolation from plant tissues using cetyltrimethylammonium bromide. Nat Protoc 1:2320–2325

Bhatia P, Ashwath N, Midmore DJ (2005) Effects of genotype, explant orientation, and wounding on shoot regeneration in tomato. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant 41:457–464

Bull SE, Owiti JA, Niklaus M, Beeching JR, Gruissem W, Vanderschuren H (2009) Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of friable embryogenic calli and regeneration of transgenic cassava. Nat Protoc 4:1845–1854

Chen M-S, Wang G-J, Wang R-L, Wang J, Song S-Q, Xu Z-F (2011) Analysis of expressed sequence tags from biodiesel plant Jatropha curcas embryos at different developmental stages. Plant Sci 181:696–700

Chetty VJ, Ceballos N, Garcia D, Narvaez-Vasquez J, Lopez W, Orozco-Cardenas ML (2013) Evaluation of four Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains for the genetic transformation of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) cultivar Micro-Tom. Plant Cell Rep 32:239–247

Costa GGL, Cardoso KC, Del Bem LEV, Lima AC, Cunha MAS, de Campos-Leite L, Vicentini R, Papes F, Moreira RC, Yunes JA, Campos FAP, Da Silva MJ (2010) Transcriptome analysis of the oil-rich seed of the bioenergy crop Jatropha curcas L. BMC Genom 11:462

Ding L-W, Sun Q-Y, Wang Z-Y, Sun Y-B, Xu Z-F (2008) Using silica particles to isolate total RNA from plant tissues recalcitrant to extraction in guanidine thiocyanate. Anal Biochem 374:426–428

Eswaran N, Parameswaran S, Anantharaman B, Kumar GRK, Sathram B, Johnson TS (2012) Generation of an expressed sequence tag (EST) library from salt-stressed roots of Jatropha curcas for identification of abiotic stress-responsive genes. Plant Biol 14:428–437

Fairless D (2007) Biofuel: the little shrub that could—maybe. Nature 449:652–655

He Y, Pasapula V, Li X, Lu R, Niu B, Hou P, Wang Y, Xu Y, Chen F (2009) Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of Jatropha curcas: factors affecting transient transformation efficiency and morphology analysis of transgenic calli. Silvae Genet 58:123

Herr J, Carlson J (2013) Traditional breeding, genomics-assisted breeding, and biotechnological modification of forest trees and short rotation woody crops. In: Jacobson M, Ciolkosz D (eds) Wood-based energy in the northern forests. Springer, New York, pp 79–99

Hirakawa H, Tsuchimoto S, Sakai H, Nakayama S, Fujishiro T, Kishida Y, Kohara M, Watanabe A, Yamada M, Aizu T, Toyoda A, Fujiyama A, Tabata S, Fukui K, Sato S (2012) Upgraded genomic information of Jatropha curcas L. Plant Biotechnol 29:123–130

Jaganath B, Subramanyam K, Mayavan S, Karthik S, Elayaraja D, Udayakumar R, Manickavasagam M, Ganapathi A (2014) An efficient in planta transformation of Jatropha curcas (L.) and multiplication of transformed plants through in vivo grafting. Protoplasma 251:591–601

Jefferson RA, Kavanagh TA, Bevan MW (1987) GUS fusions: beta-glucuronidase as a sensitive and versatile gene fusion marker in higher plants. EMBO J 6:3901–3907

Joshi M, Mishra A, Jha B (2011) Efficient genetic transformation of Jatropha curcas L. by microprojectile bombardment using embryo axes. Ind Crop Prod 33:67–77

Juan JC, Kartika DA, Wu TY, Hin T-YY (2011) Biodiesel production from jatropha oil by catalytic and non-catalytic approaches: an overview. Bioresour Technol 102:452–460

Kajikawa M, Morikawa K, Inoue M, Widyastuti U, Suharsono S, Yokota A, Akashi K (2012) Establishment of bispyribac selection protocols for Agrobacterium tumefaciens-and Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated transformation of the oil seed plant Jatropha curcas L. Plant Biotechnol 29:145–153

Kardailsky I, Shukla V, Ahn J, Dagenais N, Christensen S, Nguyen J, Chory J, Harrison M, Weigel D (1999) Activation tagging of the floral inducer FT. Science 286:1962

Khemkladngoen N, Cartagena JA, Fukui K (2011) Physical wounding-assisted Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of juvenile cotyledons of a biodiesel-producing plant, Jatropha curcas L. Plant Biotechnol Rep 5:235–243

Khurana-Kaul V, Kachhwaha S, Kothari S (2010) Direct shoot regeneration from leaf explants of Jatropha curcas in response to thidiazuron and high copper contents in the medium. Biol Plant 54:369–372

Kumar N, Reddy M (2010) Plant regeneration through the direct induction of shoot buds from petiole explants of Jatropha curcas: a biofuel plant. Ann Appl Biol 156:367–375

Kumar A, Sharma S (2008) An evaluation of multipurpose oil seed crop for industrial uses (Jatropha curcas L.): a review. Ind Crop Prod 28:1–10

Kumar N, Vijay Anand K, Pamidimarri D, Sarkar T, Reddy MP, Radhakrishnan T, Kaul T, Reddy M, Sopori SK (2010) Stable genetic transformation of Jatropha curcas via Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated gene transfer using leaf explants. Ind Crop Prod 32:41–47

Li HQ, Sautter C, Potrykus I, PuontiKaerlas J (1996) Genetic transformation of cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz). Nat Biotechnol 14:736–740

Li MR, Li HQ, Wu GJ (2006) Study on factors influencing Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Jatropha curcas. J Mol Cell Biol 39:83–89

Li MR, Li HQ, Jiang HW, Pan XP, Wu GJ (2008) Establishment of an Agrobacterium-mediated cotyledon disc transformation method for Jatropha curcas. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult 92:173–181

Li C, Luo L, Fu Q, Niu L, Xu Z-F (2014) Isolation and functional characterization of JcFT, a FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) homologous gene from the biofuel plant Jatropha curcas. BMC Plant Biol 14:125

Maghuly F, Laimer M (2013) Jatropha curcas, a biofuel crop: functional genomics for understanding metabolic pathways and genetic improvement. Biotechnol J 8:1172–1182

Makkar HP, Becker K (2009) Jatropha curcas, a promising crop for the generation of biodiesel and value-added coproducts. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol 111:773–787

Mao HZ, Ye J, Hai CN (2009) Genetic transformation of Jatropha curcas. International Publication No: WO2010071608A9

Mazumdar P, Basu A, Paul A, Mahanta C, Sahoo L (2010) Age and orientation of the cotyledonary leaf explants determine the efficiency of de novo plant regeneration and Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation in Jatropha curcas L. S Afr J Bot 76:337–344

Miguel CM, Oliveira MM (1999) Transgenic almond (Prunus dulcis Mill.) plants obtained by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of leaf explants. Plant Cell Rep 18:387–393

Misra P, Toppo DD, Mishra MK, Saema S, Singh G (2012) Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation protocol of Jatropha curcas L. using leaf and hypocotyl segments. J Plant Biochem Biotechnol 21:128–133

Murashige T, Skoog F (1962) A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant 15:473–497

Murthy HN, Jeong JH, Choi YE, Paek KY (2003) Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of niger [Guizotia abyssinica (L. f.) Cass.] using seedling explants. Plant Cell Rep 21:1183–1187

Natarajan P, Parani M (2011) De novo assembly and transcriptome analysis of five major tissues of Jatropha curcas L. using GS FLX titanium platform of 454 pyrosequencing. BMC Genom 12:191

Natarajan P, Kanagasabapathy D, Gunadayalan G, Panchalingam J, Shree N, Sugantham PA, Singh KK, Madasamy P (2010) Gene discovery from Jatropha curcas by sequencing of ESTs from normalized and full-length enriched cDNA library from developing seeds. BMC Genom 11:606

Newell CA (2000) Plant transformation technology. Mol Biotechnol 16:53–65

Pan J, Fu Q, Xu Z-F (2010) Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of biofuel plant Jatropha curcas using kanamycin selection. Afr J Biotech 9:6477–6481

Purkayastha J, Sugla T, Paul A, Solleti S, Mazumdar P, Basu A, Mohommad A, Ahmed Z, Sahoo L (2010) Efficient in vitro plant regeneration from shoot apices and gene transfer by particle bombardment in Jatropha curcas. Biol Plant 54:13–20

Qin X, Zheng X, Huang X, Lii Y, Shao C, Xu Y, Chen F (2014) A novel transcription factor JcNAC1 response to stress in new model woody plant Jatropha curcas. Planta 239:511–520

Ramamoorthy R, Kumar PP (2012) A simplified protocol for genetic transformation of switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.). Plant Cell Rep 31:1923–1931

Ramesh SA, Kaiser BN, Franks T, Collins G, Sedgley M (2006) Improved methods in Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of almond using positive (mannose/pmi) or negative (kanamycin resistance) selection-based protocols. Plant Cell Rep 25:821–828

Rosado TB, Laviola BG, Faria DA, Pappas MR, Bhering LL, Quirino B, Grattapaglia D (2010) Molecular markers reveal limited genetic diversity in a large germplasm collection of the biofuel crop Jatropha curcas L. in Brazil. Crop Sci 50:2372–2382

Sambrook J, Russell DW, Russell DW (2001) Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor

Sanderson K (2009) Wonder weed plans fail to flourish. Nature 461:328–329

Sato S, Hirakawa H, Isobe S, Fukai E, Watanabe A, Kato M, Kawashima K, Minami C, Muraki A, Nakazaki N (2011) Sequence analysis of the genome of an oil-bearing tree, Jatropha curcas L. DNA Res 18:65–76

Sharma S, Kumar N, Reddy MP (2011) Regeneration in Jatropha curcas: factors affecting the efficiency of in vitro regeneration. Ind Crop Prod 34:943–951

Singh A, Reddy MP, Chikara J, Singh S (2010) A simple regeneration protocol from stem explants of Jatropha curcas—A biodiesel plant. Ind Crop Prod 31:209–213

Sujatha M, Mukta N (1996) Morphogenesis and plant regeneration from tissue cultures of Jatropha curcas. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult 44:135–141

Sujatha M, Reddy TP, Mahasi M (2008) Role of biotechnological interventions in the improvement of castor (Ricinus communis L.) and Jatropha curcas L. Biotechnol Adv 26:424–435

Sun QB, Li LF, Li Y, Wu GJ, Ge XJ (2008) SSR and AFLP markers reveal low genetic diversity in the biofuel plant Jatropha curcas in China. Crop Sci 48:1865–1871

Tao Y-B, He L-L, Niu L-J, Xu Z-F (2015) Isolation and characterization of an ubiquitin extension protein gene (JcUEP) promoter from Jatropha curcas. Planta 241:823–836

Toppo DD, Singh G, Purshottam D, Misra P (2012) Improved in vitro rooting and acclimatization of Jatropha curcas plantlets. Biomass Bioenerg 44:42–46

Visarada K, Meena K, Aruna C, Srujana S, Saikishore N, Seetharama N (2009) Transgenic breeding: perspectives and prospects. Crop Sci 49:1555–1563

Wang Q, Xing S, Pan Q, Yuan F, Zhao J, Tian Y, Chen Y, Wang G, Tang K (2012) Development of efficient Catharanthus roseus regeneration and transformation system using Agrobacterium tumefaciens and hypocotyls as explants. BMC Biotechnol 12:34

Yao JL, Cohen D, Atkinson R, Richardson K, Morris B (1995) Regeneration of transgenic plants from the commercial apple cultivar Royal Gala. Plant Cell Rep 14:407–412

Ye J, Geng Y, Zhang B, Mao H, Qu J, Chua N-H (2014) The Jatropha FT ortholog is a systemic signal regulating growth and flowering time. Biotechnol Biofuels 7:91

Zhang L, Zhang C, Wu P, Chen Y, Li M, Jiang H, Wu G (2014) Global analysis of gene expression profiles in physic nut (Jatropha curcas L.) seedlings exposed to salt stress. PLoS ONE 9:e97878

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (31370595 and 31300568), the Natural Science Foundation of Yunnan Province (2011FA034), the West Light Foundation of CAS, and the CAS 135 program (XTBG-T02). The authors gratefully acknowledge the Central Laboratory of the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden for providing research facilities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Qiantang Fu and Chaoqiong Li have contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

11816_2015_377_MOESM1_ESM.tif

Fig. S1. Development of resistant callus of J. curcas in selection medium. (a, c) Resistant callus (indicated by red arrows) developing from the incisions of transformed cotyledon explants in selection medium supplemented with 40 mg L−1 kanamycin for 2 weeks. (b, d) No resistant callus was detected among the untransformed cotyledon explants (control). (TIFF 1976 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, Q., Li, C., Tang, M. et al. An efficient protocol for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of the biofuel plant Jatropha curcas by optimizing kanamycin concentration and duration of delayed selection. Plant Biotechnol Rep 9, 405–416 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11816-015-0377-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11816-015-0377-0