Abstract

Summary

We have characterised 997 hip fracture patients from a representative 45 Spanish hospitals, and followed them up prospectively for up to 4 months. Despite suboptimal surgical delays (average 59.1 hours), in-hospital mortality was lower than in Northern European cohorts. The secondary fracture prevention gap is unacceptably high at 85%.

Purpose

To characterise inpatient care, complications, and 4-month mortality following a hip or proximal femur fracture in Spain.

Methods

Design: prospective cohort study. Consecutive sample of patients ≥ 50 years old admitted in a representative 45 hospitals for a hip or proximal femur fragility fracture, from June 2014 to June 2016 and followed up for 4 months post-fracture. Patient characteristics, site of fracture, in-patient care (including secondary fracture prevention) and complications, and 4-month mortality are described.

Results

A total of 997 subjects (765 women) of mean (standard deviation) age 83.6 (8.4) years were included. Previous history of fracture/s (36.9%) and falls (43%) were common, and 10-year FRAX-estimated major and hip fracture risks were 15.2% (9.0%) and 8.5% (7.6%) respectively. Inter-trochanteric (44.6%) and displaced intra-capsular (28.0%) were the most common fracture sites, and fixation with short intramedullary nail (38.6%) with spinal anaesthesia (75.5%) the most common procedures. Surgery and rehabilitation were initiated within a mean 59.1 (56.7) and 61.9 (55.1) hours respectively, and average length of stay was 11.5 (9.3) days. Antithrombotic and antibiotic prophylaxis were given to 99.8% and 98.2% respectively, whilst only 12.4% received secondary fracture prevention at discharge. Common complications included delirium (36.1 %) and kidney failure (14.1%), with in-hospital and 4-month mortality of 2.1% and 11% respectively.

Conclusions

Despite suboptimal surgical delay, post-hip fracture mortality is low in Spanish hospitals. The secondary fracture prevention gap is unacceptably high at > 85%, in spite of virtually universal anti-thrombotic and antibiotic prophylaxis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Due to an increase in life expectancy [1], the burden of hip fractures is expected to reach 319 million fractures worldwide by 2040 [2], which poses a social and economic challenge for health care providers. Hip fractures are associated with an increased mortality and disability; mortality increases up to 33% at the end of the first year [3] and disability has been estimated at 5964 DALYs per 1,000 individuals [4]. In Europe, osteoporotic fractures account for a higher loss of years due to disability than most cancers [5]. Moreover, the stress of having a hip fracture affects not only the patient (due to the pain, the need of surgery and the usual long in-hospital stays) but also their family members and caregivers [6].

In this context, improving hip fracture care is becoming increasingly important for health care providers. Fracture patients are often frail and present many previous comorbid conditions [7]; hence, their management frequently requires long hospital stays and a complex process [8, 9]. For this reason, many hospitals have shifted towards a multi-disciplinary team to take care of these patients, which includes several specialities such as orthopaedists, general medicine, anaesthesiologists, rehabilitation, geriatricians, social workers, and primary care practitioners [8].

Geographical variations of hip fracture, with Spain accounting with one of the lowest hip fracture rates in Europe [10], renders comparison difficult with other national hip fracture registries reports previously published. Moreover, there is a lack of prospective accurate information on the current hospital care received by hip fracture patients, as well as on the post-operative complications and overall survival in Spain [11]. We therefore aimed to characterise patients, inpatient care (including surgery, rehabilitation, and prophylaxis of complications and/or secondary fracture prevention), inpatient complications risk, and up to 4-month mortality in a prospective cohort of Spanish hip or proximal femur fracture patients.

Methods

Study design and setting

We conducted a multi-centric, prospective cohort study in a representative 45 hospitals from 15 autonomic regions from Spain.

Participants

Inclusion criteria of contributing hospitals

Hospitals were eligible to participate in the study if they had an ortho-geriatric specialist or a medical doctor responsible for the coordination of inpatient care for hip fracture patients during their index hospital admission. The hospitals were selected considering not only their geographic representativeness but also the type/volume/size of hospital to maximise the representativeness of the study sample.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria of cases

All adults of at least 50 years old, presenting with a fragility fracture of the hip or proximal femur at any of the participating hospitals during the recruitment period (June 2014 to June 2016) were invited up to a maximum of 30 consecutive patients per hospital. Participants (or their carers if they were unable to do so) signed consent and were included at the moment of hospital admission. From then on, they received usual care according to local protocols/practice.

A fragility fracture was defined as that produced by a low energy impact or without previous traumatism. Subjects with fractures due to neoplastic disorders (including primary or metastatic bone cancer) or in an irradiated site, traffic accidents, produced by falls from a height higher than 1.80 m, peri-prosthetic or distal femur fractures, and those with a previous ipsilateral femur fracture were excluded. Additionally, patients who for any medical or psychological reason were unable to receive usual care, or those who were already participating in related (with anti-osteoporosis drug/s or fracture care/surgery as intervention/s under study) clinical trial/s were also ineligible.

Follow-up

All subjects were followed up for up to 4 months after their index admission date.

Study outcomes

The main measurements of this study were socio-demographic features of the patient (age, sex, body mass index, civil status, ethnic and educational background, place of residence previous to fracture), comorbid conditions such as previous fractures, diagnose of osteopenia, osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and secondary osteoporosis (which was confirmed if the patient had any of the following disorders related to osteoporosis: type 1 diabetes, adult osteogenesis imperfecta, hyperthyroidism or premature menopause (< 45 years old), chronic malnutrition or malabsorption, or chronic liver disease). Falls (number of falls in the last year), date of menopause, medications (anti-osteoporosis medication), fracture risk factors (FRAX tool), characteristics of the fracture episode (circumstances, site, and type of fracture), in-patient care received (pre-operative assessment, type of anaesthesia, ASA (American Society of Anaesthesiologists) physical status classification system) grade, surgery, the post-operative management (early mobilisation, constipation prevention or need or urinary catheterisation) and rehabilitation, prophylaxis of post-surgery complications, and secondary fracture prevention measures, type of multi-disciplinary units involved (group of health care professionals including physiotherapy, occupational therapy, nursery and medicine) who are responsible of the assessment and treatment of hip fracture patients) as well as baseline and post-fracture clinical outcomes (inpatient complications and up to 4-month mortality) were also collected.

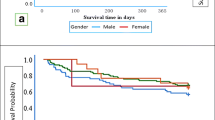

Statistical methods

A descriptive analysis was conducted for all measurements; continuous variables were summarised as mean, median, standard deviation, and quartiles (inferior, superior, minimum, maximum). The number and percentage of patients in each group was reported for each categorical variable. Kaplan-Meier curves were computed to depict post-fracture mortality up to 4 months of follow-up and after stratification per age and sex. All the analyses were stratified by sex, age, previous fractures history, and type of fracture.

Results

Baseline characteristics of study participants and contributing hospitals

A total of 997 subjects admitted to 45 hospitals were included between June 2014 and June 2016, of whom 856 (85.9%) completed 4 months of follow-up, 99 (9.9%) died in the same period, and 42 (4. 2%) were lost to follow up. Baseline characteristics of the study population are reported in Table 1. In brief, participants were mostly widowed Caucasian old women, with primary education levels, who lived in the community until they fractured. Key fracture risk factors were common, including previous fractures (36.5%) and at least one fall in the previous year (43%). Ten-year absolute fracture risk assessed using the FRAX tool was estimated at a mean (standard deviation) of 15.2% (9.0%) and 8.5% (7.6%) for major osteoporotic and hip fracture respectively. Regarding the characteristics of contributing hospitals, median (inter-quartile range) volume was of 290 (200–370) hip fractures per annum, and dedicated staff included a median (inter-quartile range) of 12 (7–15) clinicians.

Descriptive analysis

Fracture type and circumstances at the time of fracture are reported in Table 1. Hip fractures were predominantly either inter-trochanteric (44.6%) followed by intra-capsular displaced (28%), whilst 7 (0.7%) were classified as atypical femoral fractures. Most common circumstance/s leading to fracture were tripping (56.1%) or slipping (23%).

In-patient care and management of the fracture

The in-patient pre-operative care and treatments as well as the characteristics of the surgery carried out are detailed in Table 2. Upon admission, 60.6% of the subjects were assessed using a multi-disciplinary protocol, and a medical doctor reviewed 61.9% of them previous to surgery. The three most common surgical procedures carried out were (in order) (1) internal fixation with a short intramedullary nail (38.6%), followed by (2) bipolar-cemented hemi-arthroplasty (15%), and (3_ internal fixation with long intramedullary nail (14.9%). In 75.5% of these surgeries, spinal anaesthesia was used, and almost all of the subjects received either antithrombotic or antibiotic prophylaxis (99.8% and 98.2% respectively).

Different multi-disciplinary models were observed in Spanish hospitals during the whole hospital stay of the patient. An 89.5% of the participating hospitals reported formally co-ordinated care with either internal medicine or geriatrics. A multi-disciplinary protocol was used to guide care in 76.3% of the cases, and the process was usually co-ordinated by specific staff members (either specialised nurse/s or medical doctors).

Regarding surgical delays and time to rehabilitation, these were on mean (standard deviation) of 59.1 (56.7) hours and 61.9 (55.1) hours respectively. Total length of stay was of mean (standard deviation) 11.5 (9.3) days.

Post-operative care/management and complications after the fracture are summarised in Table 2. The most common inpatient complications were delirium (36.1%) and kidney failure (14.1%). The total in-hospital mortality was 2.1%.

Secondary fracture prevention

At discharge, bone health was reportedly not assessed for 23.6%, assessed but treatment deemed unnecessary/inappropriate for 20.5% of the participants. In addition, 14.9% were awaiting a bone health clinical assessment, and 3.2% were discharged pending a DXA scan before treatment. Regarding anti-osteoporosis medication/s, a 21.4% of the participants were prescribed anti-osteoporosis drug therapy at discharge (8.3% continuing previous therapy and the other 12.1% newly started treatments during hospital admission), and the percentage of such treatment increased but remained suboptimal at 32.1% and 37.8% at 1 and 4 months respectively.

Mortality in the first 4 months after discharge

Mortality in the first 4 months, overall, and stratified by sex is reported in Tables 3 and 4 and in Figs. 1 and 2. Kaplan-Meier survival estimates show an overall decreasing trend of mortality from the admission date to the end of the 4th month after the fracture, reaching 11% at the end of the 4th month. Results stratified by sex showed that men had an increased mortality after discharge compared to women (Table 4). When stratifying by age, we found that survival rates were similar in subjects up to 85 years old after which it drops drastically reaching 67% of survival rates among the oldest subjects (> 90 years old) at the end of this period (figure 3 in the supplementary material).

Discussion

In this multi-centric, prospective, observational cohort study, we found that most of the subjects with hip fracture analysed were Caucasian elderly women with previous fracture/s, falls, and an intermediate to high 10-year fracture risk. Most of the fractures were inter-trochanteric and were produced by non-traumatic accidents. The majority of the subjects were first assessed through a multi-disciplinary protocol and followed afterwards either by a specific fall prevention team or by a multidisciplinary team.

Despite hospital delay in the surgery and rehabilitation, total length of stay was not affected (11.5 days).

The most common surgical procedure carried out was an internal fixation with short intra-medullary nail with spinal anaesthesia and the most frequent complications were delirium and kidney failure. Nearly all of the subjects were previously treated with either antithrombotic or antibiotic prophylaxis.

At discharge, the majority of the subjects returned to their own home and only one fifth of them were assessed for osteoporosis treatment. Hospital mortality remained low 2.1%, and there was an overall decreasing trend in the following 4 months after the fracture.

Hip fractures result in a socio-economic burden for health care systems and are expected to increase due to the ageing of the population. Therefore, optimising the treatment and care of these fractures is a top priority for health care providers [5]. Baseline characteristics of our population did not differ from the ones analysed in other recent hip fracture registries or audits [12,13,14,15,16]. As in our report, most of them were old women with an ASA score between 2 and 3; however, our results show that a large proportion of our subjects were at an increased risk of fracture at the time of admission; over 36% reported having a previous fracture and at least one fall in the last year.

The fracture risk assessment tool (FRAX) was also calculated and despite it has been validated in many countries including Spain, an underestimation of the fracture risk among Spanish women has been previously reported [17]. To overcome this, new thresholds have been proposed [3]; low risk < 5; intermediate risk ≥ 5 to < 7.5 and high risk ≥ 7.5. If we take these thresholds into account, our population would be considered a high-risk of fracture population; however, if we take into account the original thresholds of the FRAX (low risk < 10; intermediate risk ≥ 10 to < 20; high risk ≥ 20) our subjects would be in the intermediate risk for major osteoporotic fractures and low risk for hip fractures.

When analysing the characteristics of the fracture admitted to the hospital devices and the type of surgery carried out, the majority were inter-trochanteric fractures due to slipping or tripping, which differs from some of the studies published, especially in the USA and the UK [13,14,15], where the most frequent fractures were femoral neck fractures [14], non-intertrochanteric extra-capsular fractures [15], and intracapsular fractures [13]. Seven cases were classified as atypical hip fractures. Environmental differences, such as the weather or the pavement conditions, could lead to different fracture mechanisms and, therefore, to different type of fractures. The most common surgical procedure carried out in the hospitals analysed was an internal fixation with short intra-medullary nail, which is in agreement with the type of surgery used for these fractures in some of the other registries [14, 16].

Our study reported a delay in the time to surgery and in the time to the initiation of the rehabilitation (59 and nearly 62 h after the fracture admission respectively). The Catalan Government carried out another report in 2013 and the mean delay from admission to surgery in 68% of the hospitals analysed did not exceed the 48 h [7]. Possible explanations for this increase in the delay might be related to healthcare delivery and organisational factors. Median time to surgery was also reported in the UK registry [13] and was found to be lower than ours (24.5 h). Reasons for delay in our hospitals could be due to worse patient conditions previous to the surgery (e.g. comorbidities) or because of a lower number of material means and resources to carry on the surgeries (lower number of operating rooms or surgeons). However, a main limitation of the Patel et al. study [13] is that it is based on only 1 hospital (compared to the 48 hospitals were our study was carried out), limiting its external validity. Despite the delay in the surgery our in-hospital mortality rates (2.1%) were found to be lower than that reported in other countries [12,13,14]. International comparison of mortality rates is difficult, given that not all of them measured it at the same time.

Regarding the length of stay (LOS), there is a higher variability of results in the available literature [12,13,14, 16], leading to think that it could be due to overall health care system structure and fracture care practices in the various countries and the different population analysed. A recent meta-analysis and systematic review showed that multidisciplinary care models improved the patient outcomes in terms of LOS, in-patient and long-term mortality [8]. Our results are in accordance with the actual trends of implementing a multidisciplinary care; the majority of our hospitals carried out a multi-disciplinary protocol assessed by a physician and during the post-operative care, the assessment was carried out either by a specific fall prevention team or by a multidisciplinary team, depending on the hospital analysed.

Regarding the anti-osteoporosis medication, only 20.5% of the subjects in our population were assessed for osteoporosis treatment during their hospital stay and at discharge, only 12.4% received anti-osteoporosis medication, which increased up to 37.8% in the first 4 months after discharge. The low proportion of subjects with anti-osteoporosis medication has been previously reported [16]. In a report carried out by the Catalan Government in 2013 that aimed to analyse the healthcare procedures in this region [7] among subjects aged at least 65 years old who were hospitalised because of a femur fracture, patients who had a fracture consumed 10% less anti-osteoporotic medications than those without a fracture.

Despite that the anti-osteoporosis medication is recommended by the main Spanish Traumatology Society guidelines [9] especially among subjects at high risk of fracture such as those that have already sustained a hip fracture, less than 50% of our subjects were treated at the end of the 4th month after the hip fracture. This percentage might be higher if we add those that were already taking an osteoporosis treatment before the hip fracture.

This is an observational report and therefore is subject to the limitations of this type of study. However, other limitations need to be considered; first, we were unable to gather any information regarding the possible causes of delay of the surgery/rehabilitation or determine if the LOS was influenced by the pre-fracture comorbidities of the subjects. Second, by excluding subjects who could not follow the usual practice, we might have been introducing a selection bias; however, given that our population was not excluded neither because of their comorbidities nor because of their ability to answer the questionnaires, this selection bias is probably minimum. Moreover, we were also not able to draw any casual links between the surgery, type of pre-fracture or post-fracture care received, and their recovery in terms of LOS, complications, and functionality at discharge. Finally, the low mortality rates might be related with the criteria of participating centres’ selection, which had to have some kind of “medical care” for these patients. On the contrary, our study has several strengths, as are the prospective data collection, the wide representativeness of the participating centres, selected by size and geographical region, and the consecutive sampling of cases. All these elements contribute to the external validity of the data, minimising the likelihood of bias.

Conclusions

Overall, the care of hip fractures admitted to Spanish hospitals seems in line with other registries published in recent years. The delays detected in the initiation of the surgery and rehabilitation did not affect the total length of stay or in the in-patient mortality, which were below what has been reported in other countries. As new models of care are created in order to give a better response to the patients’ needs during the care of the hip fracture, it is uncertain which model may work best. The multidisciplinary approach carried out by most of the Spanish hospitals seems to follow the latest trend in fracture patient care although secondary prevention treatment is still strikingly low.

References

Rechel B, Grundy E, Robine JM, Cylus J, Mackenbach JP, Knai C, McKee M (2013) Ageing in the European Union. Lancet 381(9874):1312–1322

Odén A, McCloskey EV, Kanis JA, Harvey NC, Johansson H (2015) Burden of high fracture probability worldwide: secular increases 2010-2040. Osteoporos Int 26:2243–2248

Azagra R, Roca G, Martín-Sánchez JC, Casado E, Encabo G, Zwart M, Aguyé A, Díez-Pérez A en representación del grupo de investigación GROIMAP(2015) FRAX® thresholds to identify people with high or low risk of osteoporotic fracture in Spanish female population. Med Clin (Barc) 144:1–8

Papadimitriou N, Tsilidis KK, Orfanos P, Benetou V, Ntzani EE, Soerjomataram I, Künn-Nelen A, Pettersson-Kymmer U, Eriksson S, Brenner H, Schöttker B, Saum KU, Holleczek B, Grodstein FD, Feskanich D, Orsini N, Wolk A, Bellavia A, Wilsgaard T, Jørgensen L, Boffetta P, Trichopoulos D, Trichopoulou A (2017) Burden of hip fracture using disability-adjusted life-years: a pooled analysis of prospective cohorts in the CHANCES consortium. Lancet Public Health 2:e239–e246

Cancio Trujillo JM, Clèries M, Inzitari M, Ruiz Hidalgo D, Santaeugènia Gonzàlez SJ, Vela E (2015) Impacte en la supervivencia i despesa associada a la fractura de fèmur en les persones grans a Catalunya. Monogràfics de la Central de Resultats, número 16. Barcelona: Agència de QualitatiAvaluacióSanitàries de Catalunya.Departament de Salut. Generalitat de Catalunya. http://observatorisalut.gencat.cat/web/.content/minisite/observatorisalut/ossc_central_resultats/informes/fitxers_estatics/MONOGRAFIC_16_fractura_femur.pdf. Accessed 12 March 2018

Siddiqui MQ, Sim L, Koh J, Fook-Chong S, Tan C, Howe TS (2010) Stress levels amongst caregivers of patients with osteoporotic hip fractures - a prospective cohort study. Ann Acad Med Singap 39:38–42

Observatori del Sistema de Salut de Catalunya Central de Resultats. Processos. La fractura de coll de fèmur en població de 65 anys o més. Dades 2014. Agència de QualitatiAvaluacióSanitàries de Catalunya. Departament de Salut. Generalitat de Catalunya, Barcelona, p 2015

Grigoryan KV, Javedan H, Rudolph JL (2014) Orthogeriatric care models and outcomes in hip fracture patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Trauma 28:e49–e55

Etxebarria-Foronda I, Caeiro-Rey JR, Larrainzar-Garijo R, Vaquero-Cervino E, Roca-Ruiz L, Mesa-Ramos M, Merino Pérez J, Carpintero-Benitez P, FernándezCebrián A, Gil-Garay E (2015) SECOT- GEIOS guidelines in osteoporosis and fragility fracture. An update. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol 59:373–393

Cauley JA, Chalhoub D, Kassem AM, Fuleihan G-H (2014) Geographic and ethnic disparities in osteoporotic fractures. Nat Rev Endocrinol 10(6):338–351

Fernández-García M, Martínez J, Olmos JM, González-Macías J, Hernández JL (2015) Review of the incidence of hip fracture in Spain. Rev Osteoporos Metab Miner. https://doi.org/10.4321/S1889-836X2015000400007

Ireland AW, Kelly PJ, Cumming RG (2015) Total hospital stay for hip fracture: measuring the variation due to pre-fracture residence, rehabilitation, complications and comorbidities. BMC Health Serv Res 15:17

Patel NK, Sarraf KM, Joseph S, Lee C, Middleton FR (2013) Implementing the national hip fracture database: an audit of care. Injury 44:1934–1939

Inacio MC, Weiss JM, Miric A, Hunt JJ, Zohman GL, Paxton EW (2015) A community-based hip fracture registry: population, methods, and outcomes. Perm J 19:29–36

Griffin XL, Parsons N, Achten J, Fernandez M, Costa ML (2015) Recovery of health-related quality of life in a United Kingdom hip fracture population. The Warwick Hip Trauma Evaluation--a prospective cohort study. Bone Joint J 97-B:372–382

Ellanti P, Cushen B, Galbraith A, Brent L, Hurson C, Ahern E (2014) Improving hip fracture care in Ireland: a preliminary report of the Irish hip fracture database. J Osteoporos 656357

Azagra R, Zwart M, Encabo G, Aguyé A, Martin-Sánchez JC, Puchol-Ruiz N, Gabriel-Escoda P, Ortiz-Alinque S, Gené E, Iglesias M, Moriña D, Diaz-Herrera MA, Utzet M, Manresa JM, GROIMAP study group (2016) Rationale of the Spanish FRAX model in decision-making for predicting osteoporotic fractures: an update of FRIDEX cohort of Spanish women. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 17:262

Acknowledgements

DPA is funded by a National Institute for Health Research Clinician Scientist award (CS-2013-13-012). This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health. This work was supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, Oxford.

Funding

Funded in part by CIBER on Frailty and Healthy Aging (CIBERFES), Instituto Carlos III, Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, FEDER funds. Unrestricted research grant from Amgen S.A. Amgen did not have any role in study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing the report, and the decision to submit the report for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

ADP is advisor or speaker for Amgen/UCB, Roche, Gilead. Institutional grant Amgen and Shareholder Active Life Sci. DPA’s research group has received unrestricted research grants from Servier, Amgen, and UCB; and speaker and consultancy fees from Amgen and UCB respectively. This work has been sponsored by an unrestricted grant of AMGEN to the Hospital del Mar Institute of Medical Investigation (IMIM). CR, MSS, JGM, LGD, CAB, SMG, DMM, EVC, MFBB, LEH, FBB, BLF, IPC, GAB, JMF, TED, JMIB, IAM, PSL, MSD, VCP, ADR, HKS, OTG, JTS, JRCR, IAC, MBC, IEF, JDAH, JRS, OTS, XN, and AH have no conflict of interests.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was obtained from each of the relevant boards of each of the hospitals participating in the study. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Electronic supplementary material

Fig. 3

(PNG 380 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Prieto-Alhambra, D., Reyes, C., Sainz, M.S. et al. In-hospital care, complications, and 4-month mortality following a hip or proximal femur fracture: the Spanish registry of osteoporotic femur fractures prospective cohort study. Arch Osteoporos 13, 96 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-018-0515-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-018-0515-8